June 9, 2025

I. introduction

In our previous post on The Demographics of Persistent Partisan Polarization we used surveys and analyses to show that the United States has entered a period of pernicious partisan polarization in the 21st century. The polarization is reinforced by political propaganda, social media echo chambers, and viral misinformation. Natural demographic pressures in choosing mates and raising children only tend to maintain that polarization in future generations. Republican voters and Democratic voters believe in distinct realities and they view each other’s motives with great suspicion. How can we as a society bridge our differences and preserve our democracy?

Bridging those differences will require changing minds, despite all the organized pressures to keep people in line within their chosen, increasingly divergent tribes. We do not expect that our blog site changes many minds by itself. Our goal is to explain the real scientific background behind issues of public policy, to help inform educators and others whose jobs are to plant the seeds of mind change. But a recent book now offers some optimism, along with basic neurological and psychological science, about developing ways all of us can actually change minds (including our own). David McRaney’s 2022 book How Minds Change (Fig. I.1) explores what he terms “the psychological alchemy of epiphanies” through a survey of relevant research and a number of case studies.

There are many examples that polarized minds can change. In a recent addendum to our posts on Flat Earth believers, we noted that famed Flat Earther Jeran Campanella admitted that he had previously been wrong about the Earth’s shape when he was personally confronted, on The Final Experiment, with his own observation that the Antarctic was indeed exposed to 24 continuous hours of sunlight in December. McRaney tells the story of Charlie Veitch, a 9/11 Truther who was previously strongly invested in the conspiracy theory that the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks in the U.S. were staged by the government rather than perpetrated by Islamic terrorists. Veitch was one of a group of 9/11 Truthers who participated in an excursion organized by the U.K. TV program Conspiracy Road Trip. After ten days in New York, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, walking the crash sites, questioning experts on demolition, explosives, skyscraper architecture, and air travel, even training themselves on a commercial flight simulator, and meeting with family members of the 9/11 victims, Veitch was the lone participant who came to doubt his previous beliefs.

We have blogged recently about an AI program, DebunkBot, that appears to have had success in talking even confirmed conspiracy believers down off the ledge. There are also multiple examples of people who have been successfully weaned off of cults; McRaney interviews a pair of young women who escaped a cult they had been embedded within since birth. And there are myriad negative examples of individuals whose minds have been changed under duress or group pressure to believe in absurdities by brainwashing, Big Lies, and YouTube conspiracy theory rabbit holes.

But why do some minds change and not others when exposed to the same information and experiences? That is McRaney’s quest in How Minds Change. The human brain’s openness to change was essential to their survival during the last Ice Age, when other hominin species – Neanderthals and Denisovans – became extinct. Openness to change allowed human innovation in creating new tools and forming social groups to aid survival when food was scarce. But there is an equally strong evolutionary pressure favoring the brain’s resistance to change, because survival also relied on avoiding premature acts based on questionable information or accepting stories told by bad actors from other tribes.

The formation of tribes led to emotional connections that could be endangered if an individual accepted beliefs antithetical to one’s tribe. Both Jeran Campanella and Charlie Veitch have been effectively excommunicated from their respective conspiracy groups by allowing their openness to new information to cast doubt on the tribe’s articles of faith. There is an emotional barrier built into the human brain that resists losing the respect of one’s tribe. Changing one’s mind often requires overcoming that emotional barrier, even emotional trauma in the case of escape from cults.

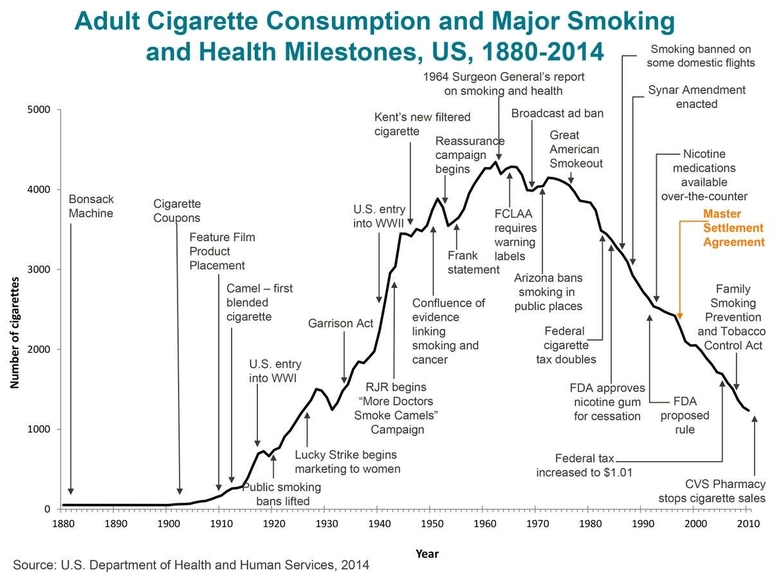

If changing individual minds is already challenging, triggering rapid social change, in which millions of minds change, is daunting. And yet it happens when conditions are right. Consider three changes in American attitudes from recent history. Figure I.2 illustrates the enormous reduction in American consumption of cigarette smoking that has taken place over half a century. The reduction began after the 1964 Surgeon General’s report warning about the dangers of lung cancer from chronic use of cigarettes but was strongly aided by a highly effective public service advertising campaign against smoking, by state and federal bans, and by aggressive taxation of cigarettes. Fundamentally, however, the change in attitudes toward smoking was triggered by science in the form of compelling epidemiological evidence of the link between smoking and lung cancer.

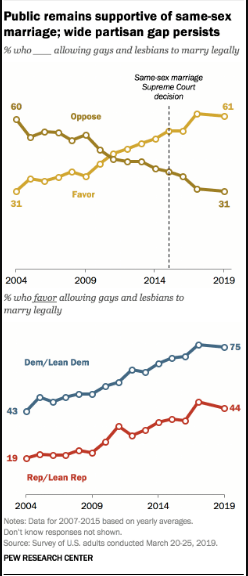

The second example, illustrated by Fig. I.3, concerns acceptance of same-sex marriage. In this case, U.S. public opinion shifted dramatically over little more than a single decade. 60% of Americans opposed same-sex marriage in 2004 but 61% had come to favor same-sex marriage by 2019. As shown in the lower frame of Fig. I.3, a significant partisan divide remains concerning same-sex marriage, but the rapid change in perceptions occurred for voters of both political parties. McRaney offers an anecdote that illustrates the rapid change even among Republicans: “When Massachusetts became the first state to pass a law granting marriage rights to same-sex couples in 2004, [President George W.] Bush publicly endorsed a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage across the country. Nine years later, the Boston Globe reported that George W. Bush would not only serve as a witness at the marriage of two women in Kennebunkport, Maine, but that he offered to perform the ceremony.”

It is notable that the change in attitudes toward same-sex marriage was not precipitated by the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court decision allowing it in the Obergefell v. Hodges case; rather, it was the change in public perceptions that made the Court decision seem less than radical. The change in attitudes was triggered by a lobbying campaign but it took hold only after the public had already undergone a half-century shift in attitudes about marriage in general, leading to a much greater emphasis on marriage for love, even without procreation.

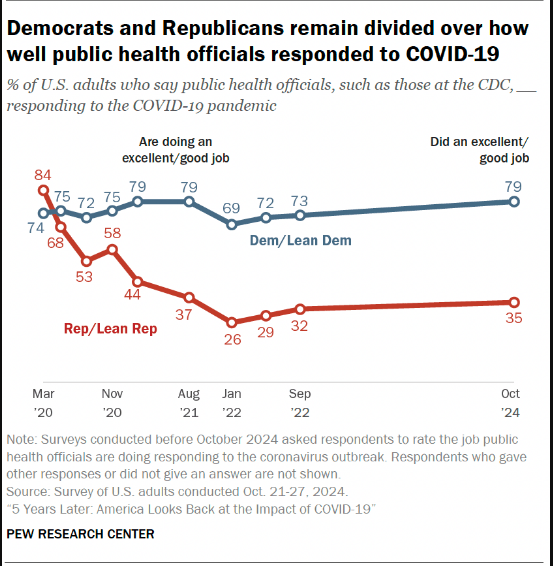

The third example of rapid social change is both more rapid and much more partisan than the same-sex marriage shift. It is also less surprising because it did not require overturning long-held views. Figure I.4 shows that Republican perceptions about public health officials changed dramatically during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic: Republican approval for public health officials’ handling of the pandemic dropped from 84% to 26% while Democratic approval held steady at 70-75%. It is interesting that this rapid decline began during a Republican administration as Republican voters placed blame for the continuing pandemic on Dr. Anthony Fauci and other public health leaders rather than on President Donald Trump’s disastrously mixed messaging about the virus. The decline was a change in tribal mindset, boosted by right-wing media and social media echo chambers, but it was not necessarily led by the leader of the tribe. In fact, during his campaign for the 2024 Presidential election, Trump found that he had to quickly drop his boasts about having managed the rapid development of COVID vaccines because the claim was so unpopular among his supporters. It is also worth noting that while Republicans strongly objected to many of the policies and even the vaccines aimed at mitigating the spread of the disease, many more of them than of Democratic voters ended up dying from COVID-19.

The data in Fig. I.4 do not represent the only rapid attitude change related to COVID-19. At the very beginning of the pandemic’s spread to Europe in December, 2019, many people polled in the U.K. said they would not accept a vaccine against COVID-19 if one were developed. However, by April 2021, after the ravages of the pandemic and the efficacy of the mRNA vaccines were clear, 86% of those who would have rejected vaccines had changed their minds.

In the case of many other social policy issues, besides the three highlighted above, American attitudes have remained more resistant to change. Part of understanding how human brains accept change, then, is also understanding why social change occasionally, but not usually, occurs rapidly. These occasional rapid changes are analogous to the paradigm shifts in the development of scientific understanding that have been highlighted in Thomas Kuhn’s influential 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In the subsequent sections of this post we will explore how human brains handle change, effective methods for changing individual minds, and the conditions for paradigm shifts in public attitudes.

II. how does the human brain handle change?

In our previous post on Brainwashing via Social Media we pointed out that “our minds, perceptions, ideas, beliefs and behaviors are creatures of neuronal habit.” The human brain is connected to billions of neurons carrying electrical and chemical signals from different body parts and sensors, and each of the neurons is subject to training by frequent stimulation. Infants learn rapidly to recognize common sights, faces, creatures, sounds, and words because the neurons excited by these perceptions are repeatedly stimulated. As a child is exposed to a wider range of perceptions the brain begins to construct a model of perceived reality that becomes capable of predictive power, knowing what to expect after established signals. McRaney describes this model of perceived reality as a hierarchy of abstractions: “At the bottom, raw sensations like shapes and sounds and colors. In the middle, concrete constructs like caterpillars and calliopes. At the top, higher concepts like humility and hurricanes. Each level depends on the levels beneath to make sense of the levels above.”

The Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget who devoted a lifetime of study to cognitive development in children called this process of learning assimilation. During assimilation, as the brain is exposed to new perceptions or phenomena it continually expands or slightly revises its hierarchical model of reality. As we age our brains remain plastic in the sense that they are still open to the training of new neural patterns. But our mental models become more elaborate, detailed, and generally more inflexible. Our mental models establish the worldviews that guide our expectations and interactions with other people and with the outside world. What happens, then, when a human brain is exposed to perceptions or experiences that appear to contradict its previously established model, its existing beliefs, attitudes, and expectations?

Such observations cause conflict in the brain. The brain has a center for assessing and resolving such conflicts, called the anterior cingulate cortex or ACC (see Fig. II.1). If the ACC is damaged or inactive it will hardly register even a clear conflict. McRaney relays the story of a stroke patient whose ACC was damaged. In a post-stroke physical exam she was able to see how many fingers the doctor held up and to see her own reflection in a mirror even though she claimed she had closed both eyes. Upon the doctor’s request her brain had sent the signal to close both eyes, but one remained open and her ACC was not available to register the conflicting information that she could still see clearly. She registered no conflict. One wonders how healthy Donald Trump’s ACC is because he seems particularly unable to update an ideé fixe, such as his belief that foreign countries pay for U.S. tariffs, or that the 2020 Presidential election was stolen from him, or that he is perpetually blameless for whatever goes wrong under his leadership, even though he is exposed to clearly contradictory real-world information.

When the ACC does register a significant conflict the brain has several choices: it can simply reject the new evidence as unreliable (e.g., “the Earth is not warming”); it can concoct a story about the new evidence that makes it seem consistent with the established mental model (e.g., “the Earth is warming but only because of ongoing natural processes that have always been at work”); or it can accept the new evidence and allow a major update to its model of reality, its beliefs and expectations (e.g., “humans really are causing global warming and this is a problem”). Piaget labeled the process by which the human brain actually updates its model in response to new conflicting information as accommodation. Piaget argued that the human brain, particularly in children, was continuously trying to establish some balance between assimilation and accommodation; the basic ideas are illustrated in Fig. II.2.

An extreme version of accommodation avoidance, characteristic of conspiracy believers, was seen by psychologist Leon Festinger, who infiltrated a Chicago doomsday cult in the 1950s. In McRaney’s telling:

“The leader of the cult, Sister Thedra, told her followers that a spaceship was coming to save them from a world-ending flood on December 21, 1954. Cult members gave away their possessions and their houses and said goodbye to their friends and their families. Then the day came and went. No spaceship. When their expectations didn’t match their reality, they experienced an enormous rush of cognitive dissonance. To resolve it, they could have accommodated and admitted that they had all been duped. But instead, they told reporters that their positive vibes had persuaded God to prevent the flood.”

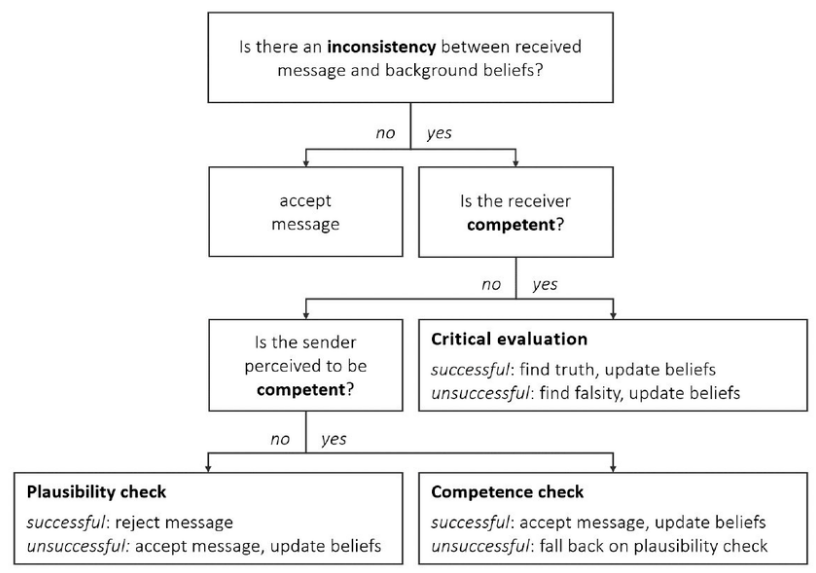

However, not all new incoming information is reliable – it may be uncertain or misinformation or disinformation — and reacting to it may be harmful to the receiving individual’s well-being. So human brains have evolved to be wary of updating the mental model too easily. This evolved resistance to mind change is known as epistemic vigilance (“epistemic” is a term from philosophy that describes phenomena related to knowledge or cognition). Figure II.3 contains a flow chart used to develop a computational model of epistemic vigilance. But the flow chart does not explicitly show an important feature of the brain’s critical evaluation processes: normally, it takes multiple examples of dissonant information to get a human brain to accommodate it.

Various psychological experiments have pointed to a threshold of conflicting information beyond which most human brains will accommodate a mind change. One of the experimenters, political scientist David Redlawsk, called this an “affective tipping point” beyond which the resistance to mind updates breaks down. Redlawsk and his colleagues simulated a Presidential election in which they frequently polled the participants for the strength of their support for their chosen candidate, as they were exposed to a steady stream of news items about their candidate, some fraction of which were intentionally negative. Participants in groups that received only 10% or 20% of negative information generally rejected that information and strengthened their candidate preference, in comparison to a control group that received no negative information. But groups that received 40% or 80% of incoming information that was negative ended up feeling quite negative about their initially chosen candidate. For most of the participants in Redlawsk’s experiments, “the tipping point came when 30 percent of the incoming information was incongruent.” But the threshold varies from individual to individual and also depends on the source of the conflicting information; information coming from a trusted colleague, a trusted news source, or other members of one’s chosen tribe has a lower threshold for getting through, while that from other tribes meets with greater resistance to accommodation.

In the progress of science, epistemic vigilance leads to a healthy skepticism, in which major updates to models or theories are accepted only after there is a sufficient body of conflicting evidence. But when carried too far, when the threshold for accommodation is too high, it can lead to the sorts of science denial that we deal with on this site, occasionally even among previously respected scientists. The mental ability to accommodate new ideas and new evidence requires an individual’s willingness to admit they were wrong previously. Narcissists generally do not have the cognitive ability to admit their own mistakes, hence, they get stuck in ideés fixes and often melt down when confronted with an overwhelming abundance of conflicting information. Donald Trump surrounds himself with sycophants to filter out conflicting information to the extent possible.

In addition to epistemic vigilance, minds face a strong emotional barrier when accommodating new information would require deviating from the shared worldview within one’s chosen tribe. For most of their existence humans, like other primates, have formed either small groups or larger tribes to cooperate in providing for life’s needs and protection from danger. Loyalty to one’s group and maintaining one’s own stature and trust within the group are fundamental drivers of human emotion. McRaney puts it this way: “humans value being good members of their groups much more than they value being right, so much so that as long as the group satisfies those needs, we will choose to be wrong if it keeps us in good standing with our peers.” This tribal psychology is the root cause of much of today’s pernicious partisan polarization in the U.S. Even established scientific facts become debatable if they are first promoted by members of an opposing group.

McRaney puts it this way: “humans value being good members of their groups much more than they value being right, so much so that as long as the group satisfies those needs, we will choose to be wrong if it keeps us in good standing with our peers.”

Psychologist Dan Kahan offers the example of tribal attitudes toward the HPV and Hepatitis B vaccines. Although both vaccines are administered to preteen girls and prevent a sexually transmitted disease that causes cancer, one became a partisan issue and the other did not. The difference is that people tended to first learn about the HPV vaccine from partisan sources on MSNBC or Fox News, and Christian conservatives decided the vaccine would lead to preteen promiscuity. In contrast, people tended to learn about the Hepatitis B vaccine from their doctors, whom they did not consider partisan operatives.

The emotional barrier against disappointing one’s chosen tribe members is what makes it so hard to wean people off conspiracy theories or out of cults. Normally, it requires some sort of independent emotional trigger, not involving arguments about information, to move a cult member to the stage of questioning their membership. This was the situation allowing Charlie Veitch to be open to information opposing his 9/11 conspiracy beliefs, after he fell in love with a woman outside his conspiracy group. McRaney’s interviews also revealed that an emotional crisis triggered the separation of two young women from their families within the virulently homophobic and antisemitic Westboro Baptist Church cult of Topeka, Kansas, after the women suffered stifling repression from the cult’s elders. It was only after these emotional separations from their groups that these people became open to questioning much of the tribal beliefs they previously shared. Wholesale upheavals of one’s worldview – radical mind changes — cause serious emotional trauma.

In discussions allowing for the possibility of changing minds it is important to be sensitive to such independent emotional triggers that may make people ready to re-evaluate. For example, it is conceivable that some believers in Donald Trump’s promoted conspiracies – stolen 2020 election, peaceful Jan. 6, 2021 protest, climate change a hoax – may soon become open to accommodate conflicting facts if they suffer the trauma of losing jobs as a result of Trump purges or Trump-induced economic instability, or if they see law-abiding friends deported to meet a Trump-imposed quota for removing immigrants from the U.S.

III. Changing minds one at a time

McRaney’s central point in How Minds Change is that the most effective methods involve empathetic one-on-one conversations, with deep and non-judgmental listening and questioning, to help receptive people probe the reasoning and the influences by which they have come to believe the things they believe. He discusses at length two street-tested approaches to such conversations that have had some significant success in opening minds.

Deep Canvassing:

The first of these approaches is called Deep Canvassing. The methods of deep canvassing were first evolved from attempts by the political action arm of the Los Angeles LGBT Center – the Leadership LAB (for Learn, Act, Build), under the direction of Dave Fleischer – to change minds about LGBTQ issues for long-term political gains. The method grew out of a post-mortem in the wake of a crushing loss in the California 2008 election, where ballot measure Proposition 8 was approved to ban same-sex marriage in the state, despite pre-election polling suggesting the measure would fail. Fleischer organized groups of canvassers to go door-to-door to ask people who had voted in favor of Prop 8 what had motivated their choice. They found that many voters who had switched to support Prop 8 had school-age children and had been influenced by ads that suggested their children would be subject to indoctrination toward homosexuality and same-sex marriage if Prop 8 failed.

After reviewing many videos taken of preliminary conversations with voters, Fleischer and his canvassers found that give-and-take conversations of canvassers with voters, usually taking about ten to twenty minutes, were promising. Canvassers could determine quickly if a voter was at all amenable to discussion about their reasons for voting a certain way. If voters were asked what they found persuasive about an ad campaign about indoctrination of children, canvassers could briefly share their own stories about ways their own parents had tried to protect them as children and ask for similar stories from the voter. Empathetic conversations, in which the canvasser made clear they really cared about hearing the voter’s perceptions and feelings, helped to build trust with those voters who were receptive to talking about their perceptions. The canvassers could ask how voters first came to learn about the issue at hand and how they began to form their opinions. They could be probed about whether those opinions and policies they supported might have negative effects on anyone they knew. They could ask about other recent events in the voter’s life and whether such events might affect their empathy toward LBGTQ people. The goal is to get voters to think about their own thinking. And gradually, through conversations that never involved debating any facts, some minds changed.

McRaney, after viewing many of the Deep Canvassing videos, described the shifts this way: “Often, it seemed as if the people who changed their minds during these conversations didn’t even realize it. They talked themselves into a new position so smoothly that they were unable to see that their opinions had flipped. At the end of the conversation, when the canvassers asked how they now felt, they expressed frustration, as if the canvasser hadn’t been paying close enough attention to what they’d been saying all along.”

An experienced canvasser described the goal to McRaney this way: “Once people see where their ideas come from, they become aware that they come from somewhere. They can then ask themselves if they’ve learned anything new in the time since they last considered them. Maybe those ideas need updating in some way. Deep canvassing is about gaining access to that emotional space, to help them unload some baggage, because that’s where mind change happens.”

You can get some flavor of a Deep Canvassing conversation from the short video in Fig. III.1, in which Caitlin Homrich-Kneileng shares her heartfelt recollections of her very first solo deep canvass conversation with a voter about minimum wage for undocumented immigrants.

After Fleischer began to publicize his group’s success in changing some minds, scientists got involved to try to quantify the impact. Political scientists David Broockman and Josh Kalla used LAB-trained Deep Canvassers in Miami to see how effective the method was in changing the minds of voters opposed to transgender bathroom rights. Voters’ opinions were surveyed over a period of months while half of them received a single Deep Canvassing intervention about transgender rights that lasted, on average, ten minutes and the other half received a “placebo,” a similar-length conversation about recycling. At the end of their experiment, Broockman and Kalla reported that “In one conversation, one in ten people opposed to transgender rights changed their views, and on average, they changed that view by 10 points on a 101-point ‘feelings thermometer.’” Furthermore, the changes persisted over the three months of the study.

That gain may seem modest, but it’s better than had been obtained with any previous method for changing voters’ minds. McRaney reports that “Kalla said a mind change of much less than that could easily rewrite laws, win a swing state, or turn the tide of an election. More than that, a shift of 1 percent had the potential to set in motion a cascade of attitude change that could change public opinion in less than a generation. This was one conversation with people who mostly had limited experience with the technique, and in Miami those conversations lasted about ten minutes each. Had the canvassers been experts, had they continued having conversations over several weeks, had those conversations been longer, the evidence suggests the impact would have been enormous.”

Broockman and Kalla have since confirmed their findings in additional experiments reported in 2020. Through a series of experiments they demonstrated that the two-way exchange central to Deep Canvassing was critical to the method’s success and that it worked just as effectively in changing minds about undocumented immigrants as it did on issues regarding transgender rights. Kalla told McRaney: “Remove the non-judgmental listening and story-sharing, no effect. Put them back in, the effect returns.”

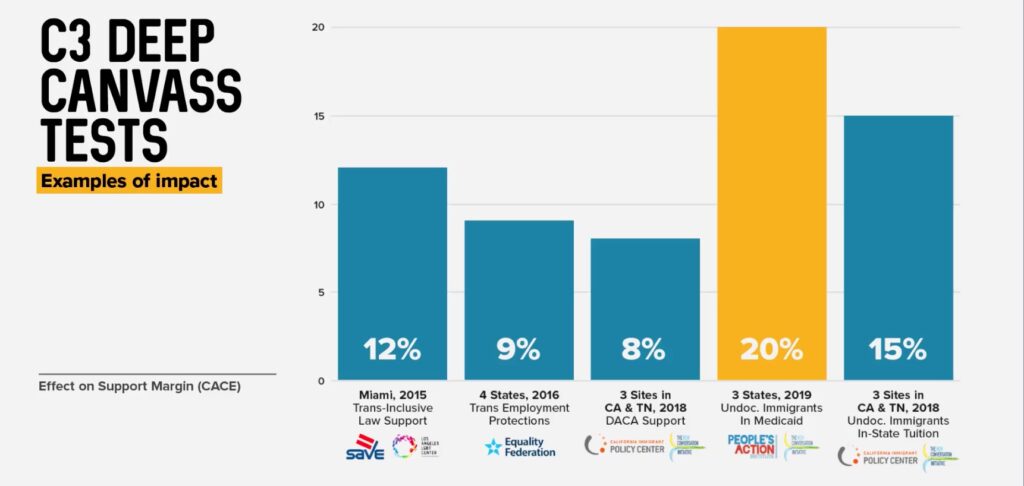

This conversational method has now been promulgated nationwide by the Deep Canvassing Institute, whose “mission is to train volunteers and organizations how to listen without judgment, share heartfelt stories that bind us together, and process conflicts in ways that result in cultural, social, and political shifts.” In their impact statement: “The Deep Canvass Institute has helped to train thousands of new deep canvassers, who have held tens of thousands of conversations around a broad range of issues from reimagining public safety, shifting the perception of immigrants, building support for public action on climate change, and persuading infrequent voters to participate in local elections. We have also helped to train hundreds of deep canvass trainers for dozens of organizations…Studies show our deep canvass conversations have been able to create the equivalent of a decade’s worth of social change in one conversation, or to successfully change minds anywhere from 17 to 102 times the power of the average persuasion effort.” Figure III.2 illustrates the effect their conversations have had in shifting the support margin on a variety of controversial public policy issues.

Street Epistemology:

Street epistemology is a conversational technique developed independently from Deep Canvassing but which shares many features with deep canvassing. It was initially developed by Anthony Magnabosco, who was then an angry atheist living in Texas and trying to understand the mindset of the many religious people that surrounded him. But he and the technique developed into a generic way to initiate deep, empathetic conversations with strangers often stopped on a street. His goal was to stimulate people to think analytically about the reasoning behind one of their deeply held beliefs. Unlike Deep Canvassing, the goal of street epistemology is not necessarily to change attitudes and certainly not to change votes, but rather to generate critical self-reflection and thus to plant seeds that, in some cases, may later lead to a person’s questioning of their own beliefs. There is, then, no obvious metric by which to measure the technique’s effectiveness, other than simply the satisfaction of both parties with the civility of each conversation and the improved mutual understanding it fosters.

The street epistemology website lays out a number of stages to an effective, empathetic conversation:

- Build and establish genuine rapport to create a safe, trusting, respectful space for meaningful dialogue.

- Identify a specific claim to explore, narrowing the discussion down to a single, clear, and meaningful belief of your conversation partner.

- Gauge confidence, using quantitative scales to explore how certain someone feels about their belief at the start of the conversation. Repeat what you’ve heard from them in your own words and iterate until they are satisfied that you understand their stance. Also clarify any terms that need to be defined so that you’re both talking about the same things.

- Explore reasons, try to unpack the justifications behind the person’s belief and judge the strength of their belief.

- Examine quality of reasoning by delving into how they assess the validity of their reasons and beliefs. This is the meat of the conversation and you have to let it develop at your partner’s pace.

To these, David McRaney adds an initial and a final stage, based on his discussions with Magnobosco and McRaney’s own experiences trying to apply the technique:

- Ask yourself “why do I want to do this?” If your goal is something other than seeking improved mutual understanding, the conversation is unlikely to succeed.

- Listen, summarize, and repeat so that the other person feels that you have honestly listened and heard what they have to say. Also thank them for their time and encourage them to continue thinking about the conversation.

Magnabosco enunciated his goals in such conversations to McRaney: “I want to know if your confidence is justified. This is not about being factually correct. I’m not an expert, and we don’t have enough time for that anyway. So instead of debating whether these claims are true or false, I just want to explore, together, whether your confidence in these conclusions is justified.” Magnabosco views each conversation as one small step toward making the world more rational and less polarized. There are by now communities at many locations around the globe who are practicing the street epistemology (SE) techniques. The SE communities comprise “individuals who value critical thinking, civil dialogue, and intellectual humility.” One site offers the tips in Fig. III.3 for both the questioner and the interlocutor in SE conversations.

Street epistemology and Deep Canvassing are two approaches to empathetic, respectful conversations about people’s attitudes and beliefs that do not rely on facts to persuade. The former aims to stimulate rational re-evaluations while the latter focuses more on emotional re-evaluations. But they are not alone. Analogous conversational techniques have been developed, for example, by Karen Tamerius of Smart Politics, and by Megan Phelps-Roper, one of those young women who left the Westboro Baptist Church cult and learned to question her previous beliefs through empathetic conversations with outsiders. All of these techniques also bear substantial similarity to the counseling approach known as motivational interviewing, intended to help people change their behavior when they are ambivalent or resistant to doing so.

DebunkBot:

The success of the above empathetic conversational techniques and previous research have suggested that bombarding an individual with facts that contradict his or her beliefs is not an effective method of persuasion. It often backfires in the same way that 10% or 20% negative information about a preferred candidate actually tended to strengthen participants’ preferences in the experiment of Redlawsk, et al. described in Section II. But what if the challenge is simply to provide enough contradictory facts to exceed the affective tipping point for an individual one wants to persuade? Some positive evidence that this may work is provided in the successes experienced to date with the AI chatbot DebunkBot, which we have described in a previous post.

DebunkBot actually uses some of the same conversational approaches as street epistemology. It establishes some form of rapport with the user – to the extent that a human can have rapport with a computer program – by engaging in a non-judgmental conversation in which it repeats what it hears in an empathetic way to establish that the user is being heard and understood. It identifies a specific claim to explore and measures the user’s level of confidence in that claim. But rather than then exploring the reasoning behind the claim, it explores the user’s arguments and patiently, calmly, and carefully rebuts them with established contradictory facts. By offering three levels of back-and-forth discussion, during which the user can present many more of the arguments they use to back up their claim, the program has the opportunity to present a wide range of contradictory facts. And, at least in the mode of weaning users off a range of common conspiracy theories, DebunkBot has had significant success, as illustrated in Fig, III.4.

On average, user confidence in their chosen conspiracy theory fell by 20% after the DebunkBot chat. A quarter of the participants actually went from predominant belief (confidence above 50%) to predominant disbelief (below 50%) in their chosen conspiracy. Furthermore, that reduction had staying power, still showing up two months after the AI chat. The reduction in conspiracy confidence was significant even for those participants who began with 100% confidence in the conspiracy. These results are comparable with the gains in changing attitudes with Deep Canvassing. The researchers’ experiments covered “a wide range of conspiracy theories, from classic conspiracies involving the assassination of John F. Kennedy, aliens, and the illuminati, to those pertaining to topical events such as COVID-19 and the 2020 US presidential election.” And an independent fact-checker found the AI to be highly accurate in presenting facts.

Human questioners have never had such success in weaning people off conspiracy theories by presenting contradictory evidence. So why does an AI program do better? In our previous post we speculated about the reasons, including the structure of the chat and the neutrality of the AI. But our main speculations were the following:

- As opposed to most sane human evidence presenters, DebunkBot has burrowed down and explored all aspects of the rabbit hole, down to the very bottom. It is thus not thrown by any argument a conspiracy believer user may launch.

- The AI furthermore has assimilated all of the effective evidence-based refutations of the conspiracist’s possible claims and is ready to present them in detail with minimal delay.

The AI thus has a better chance of getting past the subject’s affective tipping point than a human questioner. And the one-on-one exchange occurs in isolation, in the absence of possible tribal pressure to keep the user faithful to the tribe’s party line, so there isn’t a strong emotional barrier to overcome.

The fact-based approach DebunkBot uses is tailored to combating conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theorists generally pride themselves on assembling a large set of “alternative” facts that cast doubt on conventional explanations, often by “connecting random dots.” When tribal pressure is not evident – as it would be in a chat room on social media or on a group excursion like those organized by the Conspiracy Road Trip program – those alternative facts can be shown to not bear the weight of serious scrutiny. But AI and the accumulation of conflicting facts are less well suited than Deep Canvassing or street epistemology to change attitudes about such social policy issues as same-sex marriage or undocumented immigrants, or to stimulate critical self-evaluation of one’s own thought processes. The best technique to use for persuasion depends on the subject being addressed.

IV. social change and paradigm shifts

None of the techniques described in Section III is easy. It is hard work even to change a single mind. A typical Deep Canvassing or street epistemology conversation lasts ten minutes and has about a 10% chance of leading to a change of attitude or belief. So roughly two person-hours are needed to change a single mind. How, then, do you change millions of minds to effect social change?

Paradigm shifts:

The task is not quite as daunting as that latter calculation suggests because, just as each individual has an affective tipping point beyond which their brains update to accommodate conflicting information, societal attitudes also tend to have tipping points to shift dramatically beyond some amount of contrary evidence or number of convinced individuals. These attitudinal tipping points are related to the paradigm shifts in the history of science that have been highlighted by Thomas Kuhn in his influential 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. According to Kuhn, an accepted paradigm that has long provided the model or theory used to interpret a class of natural phenomena begins to be called into question when anomalies that have escaped explanation pile up and a groundbreaking work offers a radically new explanation. This leads to the creation of novel tests of the new explanation. If these are successful, the new explanation begins to attract other early adopters. Eventually, with enough adopters, the new explanation replaces the old paradigm, although there are always holdouts. David McRaney points out that this basic sequence is involved in all societal changes: “Large groups of people change their minds in a sequence that goes from innovator to early adopter to mainstream to holdouts, and it always happens in that order.”

Paradigm shifts in science have sometimes taken centuries from innovator to mainstream. Consider two of the most profound paradigm shifts in the history of science. Nicolaus Copernicus showed in 1543, just before his death, that a heliocentric model in which the Earth and other planets orbited the Sun gave a much simpler explanation for astronomical observations of the positions of the planets than the many-centuries-old Ptolemaic model based on the Sun and other planets orbiting the Earth in sometimes very complicated patterns. The Catholic and Protestant Churches tried for centuries to suppress both Copernicus’ work and Galileo’s 1632 work Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, which favored Copernicus’ theory. Only after Isaac Newton’s 1713 second edition of his Principia included a Law of Universal Gravitation and a quantitative account for the observed motions of the planets did Copernicus’ revolution attract numerous adopters. And the heliocentric model only became the new paradigm by the end of the 18th century.

The paradigm shift that arose from Charles Darwin’s innovative 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species took the better part of a century to play out. Evolution by natural selection only became widely accepted as a new paradigm after chromosomes were discovered at the end of the 19th century and Thomas Hunt Morgan and Theodosius Dobzhansky carried out experiments in the 1920s and 1930s that clearly demonstrated the occurrence of genetic mutations and the separation of species. It was those experiments that provided the microscopic mechanism for evolution. Dobzhansky’s 1937 book Genetics and the Origin of Species became the foundation for the modern synthesis of evolutionary theory. And as we have outlined in detail in our previous post on Evolution, many holdouts remain because this scientific paradigm is at odds with a literal interpretation of the Judaeo-Christian Bible.

The time period from innovation to acceptance as the new paradigm grew somewhat shorter in the 20th century but still took decades for the scientific revolutions of Quantum Mechanics, Relativity, and the Big Bang theory of the universe’s birth. In each case, critical experiments provided compelling new evidence for the innovative theories. Acceptance became quicker as the number of scientists working in the relevant fields grew, communications among them became more rapid, and the technology used in experiments that could test promising new theories underwent their own revolutions.

We have also described in previous posts the tipping points in societal attitudes and public policy that were triggered by scientific findings in the cases of the banning of DDT and the need to address the depletion of the stratospheric ozone layer. In the case of the pesticide DDT, it took a decade from Rachel Carson’s 1962 publication of Silent Spring before the newly established U.S. Environmental Protection Agency first banned DDT use for U.S. crops. In the case of the ozone layer, 14 years passed from the 1974 publication by Sherwood Roland and Mario Molina first showing how chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) destroyed stratospheric ozone until the 1988 adoption of the Montreal Protocol in which the world’s countries all pledged to phase out CFC production. In both of these cases the delay from innovation to acceptance was filled with strong opposition to the new scientific findings, not from the Church but from industries whose bottom line was threatened by those findings. And holdouts in both cases continue to this day.

The successful paradigm shifts in public attitudes and policies in these two cases illustrated two important features of changing minds on issues at the interface of science and public policy: (1) there needs to be clear scientific evidence of problems presented to the public in compelling, easily comprehensible ways, like the graphs showing the rapidly growing ozone hole over the Antarctic; (2) at least some corporations in affected industries need to be brought on board with proposed policy changes. But industries have gotten better organized since the mid-20th century, have hired their own scientists to cast doubt on the public (and even their own private) evidence, and have exercised considerable political clout to oppose policy changes and resist overwhelming acceptance of societal attitude changes. These are the factors, for example, that now complicate widespread acceptance of the urgency to mitigate human-caused climate change.

The stages of social change:

Tribal psychology, nowadays reinforced by social media echo chambers, impedes social change. In order to generate a cascading opinion that can take hold widely, it is essential to get at least a few members of a resistant tribe to establish contacts with people outside that tribe. Even within a group that has strong internal connections, different individuals have different affective tipping points, different thresholds for accepting new ideas. Each member’s threshold is generally higher for accepting ideas that deviate from group orthodoxy.

Society comprises a network of tribes. Suppose that a new idea, such as the need to mitigate human-caused climate change, has spread within one group whose members are open to the scientific evidence. Many members of a resistant group may not even be aware of the evidence. If a few members of a resistant group who have communications with several members of the accepting group learn of the evidence from multiple contacts and find it above their own threshold for accommodation, they can begin to spread that information with their close contacts within the resistant group. At that point, several alternative processes can begin: (1) the person bringing contradictory evidence to the group may be effectively excommunicated by the keepers of the orthodoxy, as has happened to Jeran Campanella and Charlie Veitch (see Section I) when they started questioning conspiracy theories about a flat earth and 9/11, respectively; (2) that person may remain in the resistant group as something of a contrarian, but an insufficient number of other members accept the new evidence to generate a cascade; (3) the person with outside contacts can initiate a cascade of acceptance within the initially resistant group. It is process (3) that then leads to widespread social change. There will be holdouts – there always are — those with difficult-to-meet thresholds or members of cult-like groups that remain completely disconnected from the rest of society. But social change does not rely on universal acceptance.

The initial stage of social change is thus always changing one mind at a time; if the mind that changes belongs to a resistant group it may go a long way. To quote David McRaney: “The fact that the state of the network determines whether global cascades are possible explains not only why some ideas catch on and others do not, but why some ideas appear over and over again and go nowhere until one day they change everything… Societies aren’t fixed. Large social systems, though they seem stable, are always changing in subtle ways that are imperceptible to the people living within them.”

Psychologist Lesley Newson and zoologist Peter Richerson predicted in 2009 that American attitudes toward same-sex marriage would change rapidly at some point in the future because the environment of a wealthy and stable society eventually leads toward expanded tolerance of previously disregarded groups. Acceptance for same-sex marriage would follow the acceptance over the late 20th century of marriage for love and not necessarily for procreation and the acceptance of homosexuality as more people came into daily contact with gays and lesbians who had “come out.” But Newson and Richerson could not predict precisely when the same-sex marriage attitudes would shift dramatically. But efforts like Deep Canvassing, working on one mind at a time, helped to trigger the shift (see Fig. I.3) over the decade following Newson and Richerson’s paper.

The initial stage of social change is thus always changing one mind at a time; if the mind that changes belongs to a resistant group it may go a long way…persistence must continue even after majority opinion has shifted because some of the holdouts often work to instigate a backlash to the change.

It is generally difficult to predict when the structure of social networks becomes susceptible to global cascades. So, the key to generating social change is persistence, continuing to try to change one mind at a time using one of the approaches described in Section III. And that persistence must continue even after majority opinion has shifted because some of the holdouts often work to instigate a backlash to the change. For example, in his concurring opinion in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision overturning the right to abortion, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas signaled his eagerness for the Court to also revisit the 2015 same-sex marriage decision in Obergefell v. Hodges. The Southern Baptist Church is now voting on whether they should formally oppose same-sex marriage. Rights for LGBTQ groups may get rolled back for political reasons (for example, Donald Trump maintaining his support from evangelical Christians) even though those rights now have majority support in the U.S. So persistence in changing minds continues to be necessary.

McRaney again: “persistence plus luck is what changes minds, not genius. The ideas that change the world are the ones in the heads of people who refuse to give up.”

References:

D. McRaney, How Minds Change (Penguin Random House, 2022), https://www.davidmcraney.com/howmindschangehome

DebunkingDenial, The Demographics of Persistent Partisan Polarization, https://debunkingdenial.com/the-demographics-of-persistent-partisan-polarization/

DebunkingDenial, Flat Earth ‘Theory’, Part I, https://debunkingdenial.com/flat-earth-theory-part-i/

The Final Experiment, https://www.youtube.com/@The-Final-Experiment

BBC, Conspiracy Road Trip, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01nbt65

DebunkingDenial, Can AI Wean People Off Conspiracy Theories?, https://debunkingdenial.com/can-ai-wean-people-off-conspiracy-theories/

DebunkBot, https://www.debunkbot.com/

DebunkingDenial, Brainwashing via Social Media, https://debunkingdenial.com/brainwashing-via-social-media/

Wikipedia, Tobacco in the United States, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tobacco_in_the_United_States

Pew Research Center, Majority of Public Favors Same-Sex Marriage, but Divisions Persist, May 14, 2019,https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/05/14/majority-of-public-favors-same-sex-marriage-but-divisions-persist/

Wikipedia, Obergefell v. Hodges, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Obergefell_v._Hodges

Pew Research Center, 5 Years Later: America Looks Back at the Impact of COVID-19, Feb. 12, 2025, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2025/02/12/5-years-later-america-looks-back-at-the-impact-of-covid-19/

DebunkingDenial, Ten False Narratives About the Coronavirus, https://debunkingdenial.com/ten-false-narratives-about-the-coronavirus-part-i/

DebunkingDenial, Live Free AND Die: Why Republican Voters are Dying Younger than Democratic Voters, https://debunkingdenial.com/live-free-and-die-why-republican-voters-are-dying-younger-than-democratic-voters/

NPR, The Fight to Change Attitudes Toward COVID-19 Vaccines in the U.K., April 19, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/04/19/988837575/the-fight-to-change-attitudes-toward-covid-19-vaccines-in-the-u-k

Wikipedia, Paradigm Shift, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paradigm_shift

Wikipedia, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Structure_of_Scientific_Revolutions

Wikipedia, Jean Piaget, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Piaget

D. Sperber, et al., Epistemic Vigilance, Mind and Language 25, 359 (2010), https://www.dan.sperber.fr/wp-content/uploads/EpistemicVigilance.pdf

D. Reisinger, M.L. Kogler, and G. Jäger, On the Interplay of Gullibility, Plausibility and Criticism: A Computational Model of Epistemic Vigilance, Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulations 26, 8(2023), https://www.jasss.org/26/3/8.html

D. Redlawsk, A.J.W. Civettini, and K.M. Emmerson, The Affective Tipping Point: Do Motivated Reasoners Ever “Get It”?, Political Psychology 31, 563 (2010), https://www.jstor.org/stable/20779584

Anti-Defamation League, Westboro Baptist Church, https://www.adl.org/resources/profile/westboro-baptist-church

Deep Canvass Institute, Want to Change Hearts and Minds?, https://deepcanvass.org/

BRIC Foundation, Dave Fleischer, https://www.bricfoundation.org/profile/3emkk-96gw8

D. Broockman and J. Kalla, Durably Reducing Transphobia: A Field Experiment on Door-to-Door Canvassing, Science 352, 220 (2016), https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aad9713

J.L. Kalla and D.E. Broockman, Reducing Exclusionary Attitudes Through Interpersonal Conversation: Evidence from Three Field Experiments, American Political Science Review 114, 410 (2020), https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/abs/reducing-exclusionary-attitudes-through-interpersonal-conversation-evidence-from-three-field-experiments/4AA5B97806A4CAFBAB0651F5DAD8F223

E. Lempinen, Want to Persuade an Opponent? Try Listening, Berkeley Scholar Says, UC Berkeley News, June 26, 2020, https://news.berkeley.edu/2020/06/26/want-to-persuade-an-opponent-try-listening-berkeley-scholar-says/

Deep Canvass Institute, Our Impact, https://deepcanvass.org/our-impact/

Street Epistemology, Critically Reflective Conversations for Everyone, https://www.streetepistemology.com/

D. Robertson, Anthony Magnabosco: An Honest Attempt to Claw a Bit Closer to the Truth, Plato’s Academy Centre, April 12, 2021, https://platosacademy.org/anthony-magnabosco-an-honest-attempt-to-claw-a-bit-closer-to-the-truth/

Street Epistemology, Find the Community for Your Interests and Goals, https://www.streetepistemology.com/communities

The Guild of the Rose, Intro to Street Epistemology, https://guildoftherose.org/articles/intro-to-street-epistemology

Smart Politics, It’s Not Too Late to Change Minds, https://www.joinsmart.org/

M. Phelps-Roper, I Grew Up in the Westboro Baptist Church. Here’s Why I Left, TED Talk, Feb. 2017, https://www.ted.com/talks/megan_phelps_roper_i_grew_up_in_the_westboro_baptist_church_here_s_why_i_left

Understanding Motivational Interviewing, https://motivationalinterviewing.org/understanding-motivational-interviewing

G.J. Trevors, et al., Identity and Epistemic Emotions During Knowledge Revision: A Potential Account for the Backfire Effect, Discourse Processes 53, 339 (2016), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163853X.2015.1136507

T.H. Costello, G. Pennycook, and D.G. Rand, Durably Reducing Conspiracy Beliefs Through Dialogues with AI, Science 385, eadq1814 (2024), https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adq1814

DebunkingDenial, Conspiracy Theory True Believers, Part II: The Mindset of True Believers, https://debunkingdenial.com/conspiracy-theory-true-believers-part-ii-the-mindset-of-true-believers/

Wikipedia, Nicolaus Copernicus, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicolaus_Copernicus

Wikipedia, De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_revolutionibus_orbium_coelestium

Debunking Denial, The Desperation of Book Bans, Part I: Book Bans Through History, https://debunkingdenial.com/the-desperation-of-book-bans-part-i-book-bans-through-history/

Wikipedia, Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newton’s_law_of_universal_gravitation

Wikipedia, On the Origin of Species, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_the_Origin_of_Species

Wikipedia, Thomas Hunt Morgan, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hunt_Morgan

Wikipedia, Theodosius Dobzhansky, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodosius_Dobzhansky

Wikipedia, Genetics and the Origin of Species, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genetics_and_the_Origin_of_Species

DebunkingDenial, Evolution, Part I: Concepts and Controversy, https://debunkingdenial.com/evolution-part-i-concepts-and-controversy/

DebunkingDenial, Scientific Tipping Points: The Banning of DDT, https://debunkingdenial.com/scientific-tipping-points-the-banning-of-ddt-part-i/

DebunkingDenial, Scientific Tipping Points: The Ozone Layer, https://debunkingdenial.com/scientific-tipping-points-the-ozone-layer/

Wikipedia, Rachel Carson, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rachel_Carson

Wikipedia, Silent Spring, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silent_Spring

M.J. Molina and F.S. Rowland, Stratospheric Sink for Chlorofluoromethanes: Chlorine Atom-Catalysed Destruction of Ozone, Nature 249, 810 (1974), https://www.nature.com/articles/249810a0

Wikipedia, Montreal Protocol, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montreal_Protocol

DebunkingDenial, Scientific Tipping Points: Lessons Learned for Climate Change, https://debunkingdenial.com/scientific-tipping-points-lessons-learned-for-climate-change/

DebunkingDenial, Epidemiology Busters: Scientists for Hire to Defend Toxic Products, https://debunkingdenial.com/part-i-epidemiology-busters-scientists-for-hire-to-defend-toxic-products/

L. Newson and P.J. Richerson, Why Do People Become Modern? A Darwinian Explanation, Population and Development Review 35, 117 (2009), https://www.des.ucdavis.edu/faculty/richerson/NewsonRichersonWhyModern.pdf

Oyez, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, https://www.oyez.org/cases/2021/19-1392