July 2, 2020

I. Growth of the Product Defense Industry

Unregulated capitalism is bad for your health. The unfettered “free market” is not free. You pay for it with years removed from your life expectancy, with progressively increasing fractions of your family budget devoted to health care, with the costs incurred to combat effects from a deteriorating environment. Companies that develop lucrative products are loathe to dent their bottom lines by mitigating, or even acknowledging, serious health hazards their products may pose to users and the environment. Those hazards are generally revealed through massive epidemiological research projects, which analyze health records of very large samples of individuals to search for significantly greater prevalence of certain diseases or injuries among people who have greater exposure to certain types of products or work environments. These studies are sometimes supplemented by animal research. For corporations that market such products, epidemiology and the government regulations the research might stimulate become enemies to be outwitted and blocked.

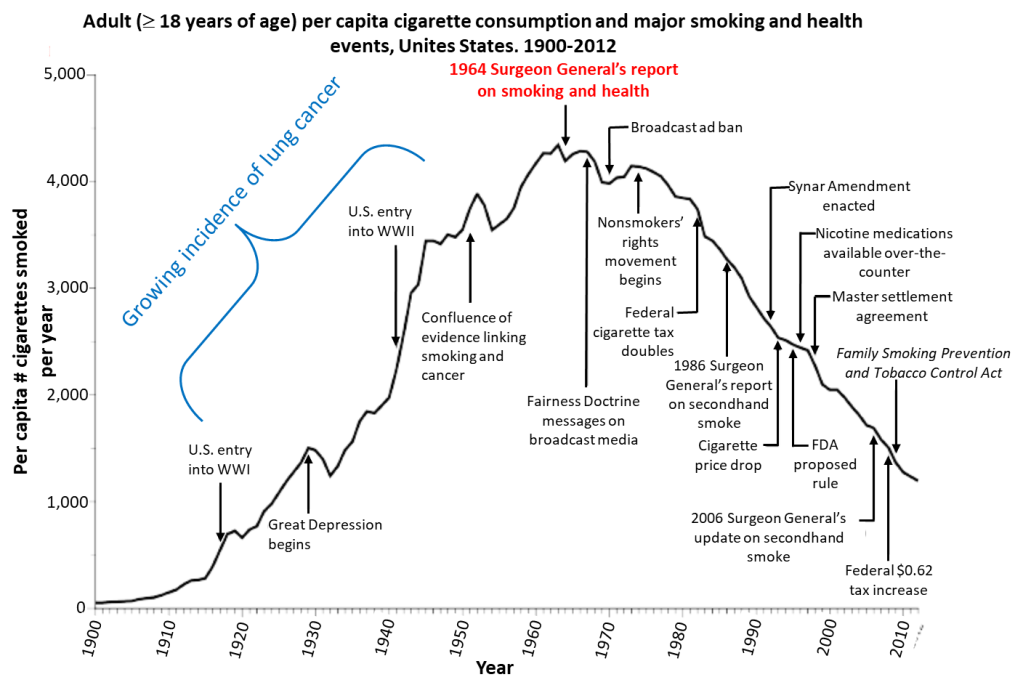

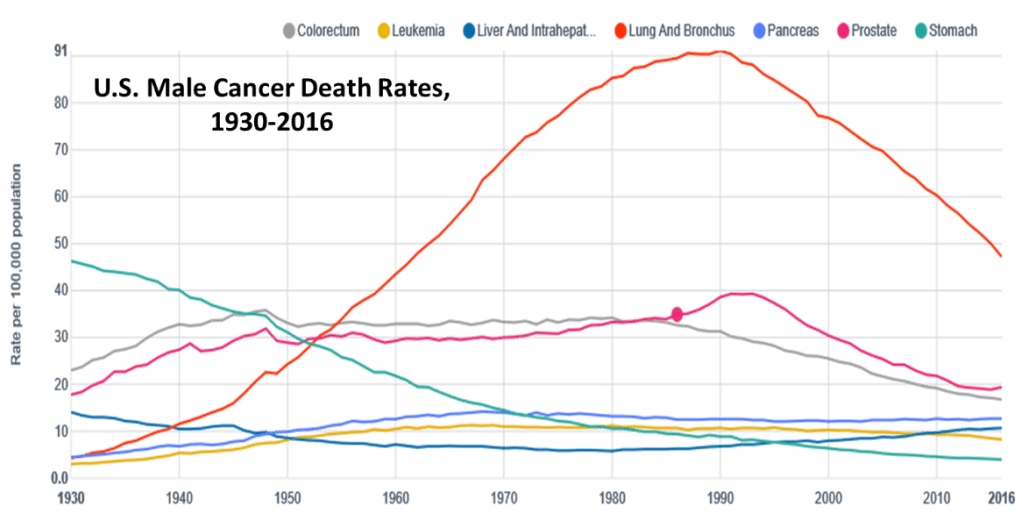

The classic case of epidemiological studies that threatened the bottom lines of a major industry is the research done in the mid-20th century to establish the strong and clear linkage between tobacco smoking – and eventually even second-hand smoke – and lung cancer. That research led eventually to the adoption of legislation introducing both taxation and regulations on tobacco products. Some of the historical events marking the evolution of smoking in the U.S. are summarized in Fig. 1, while the impact of the regulations on the incidence of lung cancer deaths among American males is illustrated in Fig. 2. The figures show the dramatic rise in consumption of aggressively marketed cigarettes and in lung cancer deaths during the first half of the 20th century. Since the incidence of lung cancer lags 20—25 years behind the incidence of smoking, it took some time to establish the epidemiological link between the two. But it is also very clear from the figures that the onset of government taxation and regulatory actions, together with an aggressive public service advertising campaign, during the second half of the 20th century has produced an equally dramatic decrease in both cigarette consumption and lung cancer incidence.

The tobacco industry fought tooth and nail against the epidemiological science and the government regulations all the way, despite the fact that the link between smoking and lung cancer is among the clearest and strongest known among epidemiological studies. (For example, a recent study concludes that men who smoked cigarettes for 40-60 pack-years – i.e., average number of packs per day times number of years duration of the habit – were nearly 10 times as likely to develop lung cancer than non-smokers, while for women those odds increase by a factor of 25.) That fight continued for decades past the tipping point associated with the 1964 Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health. It continued despite the industry’s own early awareness – retroactively revealed through discovery in litigation during the 1990s – of both the cancer risk and the addictive nature of cigarettes.

The battle was waged on both scientific and public relations fronts. The tobacco industry engaged Hill & Knowlton, an advertising firm that soon organized a division of scientific, technical and environmental affairs within a newly established Tobacco Industry Research Committee, to help with all aspects of their struggle. And though the industry eventually lost the war and finally suffered financial penalties well over 100 billion dollars in the 1990s, its strategies served to delay the inevitable losses for decades, during which it continued to reap enormous profits from the sale of hazardous products.

The techniques adopted by the tobacco industry established a basic playbook that has been copied by many diverse industries ever since. Hill & Knowlton’s success in helping Big Tobacco to delay its losses has spawned a product defense industry, with numerous large consulting firms now offering their services to stave off government regulation of hazardous products and minimize litigation losses. Many of these firms got involved in the tobacco industry’s battles over the years. The services they provide include public relations and legal support, but most significantly they include scientists for hire to refute or cast doubt on epidemiological research, to identify other products from different industries as the real culprits, to argue that the risks disappear below threshold exposures that are well above those associated with their clients’ products, and even, in rare instances, to carry out new research in an attempt to refute the risks.

When faced with product jeopardy from research exposing the health hazards, who’re you gonna call? Epidemiology-busters! There is no shortage of industries eager to pay for these services. They include producers of carcinogenic products (e.g., cigarettes, diesel fumes, asbestos, talc, etc.), of toxic chemicals (e.g., in lead-based paints, in Teflon and Scotchgard, in various pesticides and weed-killers), of drugs with lethal side-effects (e.g., Merck’s Vioxx), of obesity- and diabetes-inducing products (e.g., sugary drinks and foods), of addictive products (e.g., nicotine and opioids). They also include industries that expose their workers to severe injuries and illnesses, such as permanent brain damage to NFL football players, respiratory failure among miners, silicosis and cancer among construction workers. And they prominently feature industries whose emissions of fine particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, ozone, and greenhouse gases contribute strongly to environmental hazards to health of the entire public.

All of these industries make the economic judgment that the costs of product defense, and even of eventual possible litigation settlements, are far lower than the profit losses they would suffer by admitting early to the health hazards their products cause. And furthermore, the resources they are willing to devote to product defense usually dwarf those available to government agencies charged with ensuring the health and safety of the American public.

The science denial efforts made across all these industries by product defense consultants have now been exposed in considerable insider-level detail in a new book, entitled The Triumph of Doubt, by David Michaels, as well as in his previous book Doubt is Their Product. Michaels is an epidemiologist who headed the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) within the Department of Labor under President Obama. OSHA is one of the U.S. federal agencies charged with regulating hazardous environments and products, along with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the Department of Agriculture (DOA), the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), and a few others. The Triumph of Doubt is an outstanding resource for understanding both the elements and applications of the epidemiology-busters’ playbook, and we will summarize some of those elements, along with the members of the product defense network, in the following sections of this post. We will also include case histories for two illustrative product defense campaigns in Part II of this post.

The scientists for hire at product defense firms are not doing anything illegal. They provide a service most akin to that of defense lawyers, an honorable profession. Like defense lawyers, they start from the conclusion that their client is innocent (otherwise they are unlikely to get paid, whether or not they actually believe in that innocence), and they endeavor to find the most effective ways to either demonstrate that innocence or, more generally, to cast doubt on parts of the prosecution’s case. But there are important differences. First of all, government regulatory decisions should be based upon the preponderance of the evidence regarding a product’s health hazards, rather than requiring legal proof “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Second, in contrast to product defense scientists, defense lawyers make no claim that they are providing unbiased, independent opinions and judgments. Their goal of “delivering” for their clients is clear to all. But product defense specialists are unwilling to admit that they are engaged for the most part in pseudo-scientific denial, starting from their clients’ desired conclusion and then cherry-picking, misrepresenting or doctoring the evidence to reach that conclusion. As Michaels puts it: “The corporations and their hired guns market their studies and reports as ‘sound science,’ but actually they just sound like science.”

They maintain the illusion of legitimate science by publishing peer-reviewed articles, but these appear most often in friendly, industry-funded journals. When required by journals to note their funding sources, they provide as little information about those sources as they can get away with. And they are generally not required to reveal their present or past funding sources when they write op-eds, submit public comments to proposed government regulations, offer expert testimony in Congress or in court cases, or take on roles in regulatory agencies in subsequent administrations.

II. Who Are the Players in the Product Defense Network?

The Consultants:

The product defense network is centered around a handful of large consulting firms which offer clients public relations, epidemiology denial and legal support for often decades-long campaigns to keep harmful products on the market and free from national or international designation as health hazards (see Fig. 3). These firms are aided and abetted in their efforts by industry-funded trade/research/lobbying/front organizations with carefully chosen attractive names, and by astroturf (faux grassroots) “think tanks” that use industry support to push extreme libertarian views opposing government regulation of any sort. The allegedly independent “scientific” studies the product defense firms carry out to cast doubt on epidemiological results are generally published in a small number of peer-reviewed journals whose funding support also comes primarily from the affected industries. The product defense firms often collaborate with legal firms, with funding and coordination sometimes funneled through the lawyers so that communications can be shielded by attorney-client privilege from discovery searches in potential future lawsuits. And the scientists involved in minimizing toxic risks often end up moving back and forth between the product defense industry and the government regulatory agencies charged with protecting public health and the environment.

The most venerable of the product defense firms is Hill & Knowlton Strategies, which was first established in 1927. Their primary focus is on public and media relations, and business reputation and crisis management. As is the case for many of these firms, Hill & Knowlton’s self-description paints them as a progressive organization interested in improving lives: “Our consultants have the expertise and passion to help brands have a Better Impact™ on people and the planet… We work with organizations that want to be better – we don’t judge past actions. What matters is that your intentions are authentic, and you are committed to turning them into action.” One would be hard-pressed to discern that core interest in improving impacts on people and the planet from their track record. In addition to their coordination of efforts by the tobacco industry in the mid-20th century to combat the link of cigarettes to lung cancer, they have played similar roles in denying health and environmental risks associated with asbestos, vinyl chloride, chlorofluorocarbons, dioxin, and lead and beryllium poisoning. They are one of a number of firms currently engaged in protecting the interests of fracking companies. They often collaborate with other product defense specialists with more science-denying expertise; for example, Fred Singer – a science denier frequently highlighted on this site – was a frequent collaborator on some of their efforts to defend toxicity.

Exponent, established in 1970, is one of the older scientific consulting firms heavily devoted to product defense. Their website advertises that “Our scientists, physicians, and regulatory specialists provide unparalleled, interdisciplinary expertise to evaluate the full range of environmental and public health issues that face our nation and the world. These issues include potential environmental and health effects associated with environmental agents, chemicals, consumer products, food safety and nutrition, and pharmaceutical products. Indeed, members of our staff are leaders in developing the risk assessment methodologies that are essential to address the complexities of these issues.” They have, for example, exploited these “complexities” to argue against declaring second-hand smoke, silica exposure, or the chemical glyphosate (contained in Monsanto’s Roundup weed killer, one of the case studies we will detail in Part II of this post) as carcinogenic agents. They have minimized the risk of immune system damage from perfluorinated chemicals (the PFAS involved in Teflon and 3M’s Scotchgard, another case to be highlighted in Part II), of respiratory disease from miners’ exposure to diesel exhaust, and of mesothelioma from asbestos exposure associated with a joint compound developed by Georgia Pacific.

Gradient Corporation, established in 1985, is a major player in toxic product defense. They advertise themselves as “an environmental and risk sciences consulting firm renowned for our specialties in Toxicology, Epidemiology, Risk Assessment, Product Safety, Contaminant Fate and Transport, Industrial Hygiene, Geographic Information Systems, and Environmental/Forensic Chemistry.” They are quite up-front about their focus on toxic products. Among a much longer list of chemical products they’ve consulted on, they include all of the following: asbestos, beryllium, BPA, chromium, DDT, diesel exhaust, dioxins, flame retardants, heavy metals, lead, mercury, nanoparticles, NO2, ozone, PCBs, pesticides, petroleum hydrocarbons, fine particulate matter (PM2.5), vinyl chloride, and perfluorinated chemicals. Essentially a toxic chemical Hall of Fame (or infamy).

The Gradient website crows that “Our scientists have a long history of advancing the field of risk sciences by developing novel approaches, authoring noteworthy peer-reviewed publications, serving on scientific advisory panels, and providing scientific input on health risk issues underlying environmental regulations.” As for those noteworthy peer-reviewed publications, an analysis by the Center for Public Integrity found that since 1992, half of all research articles published by Gradient’s top scientists appeared in either Critical Reviews in Toxicology or Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, two industry-funded journals we will discuss further below. And their “novel approaches” to risk sciences, across many industries, are highlighted both in David Michaels’ book and in the Center for Public Integrity article “Meet the ‘Rented White Coats’ Who Defend Toxic Chemicals.” Authors of the latter article “analyzed 149 scientific articles and letters published by the firm’s most prolific principal scientists. Ninety-eight percent of the time, they found that the substance in question was harmless at levels to which people are typically exposed.”

Another firm with a somewhat similar profile to Gradient is ChemRisk (now Cardno ChemRisk), also established in 1985. “We specialize in understanding the epidemiologic literature for many chemicals, and are experienced at characterizing hazards using a weight-of-the-evidence approach, or meta-analysis…We always consider the impact of other potential exposures in any given situation. Our work has clarified many health risk issues, guided regulatory decision-making, and improved the safety and sustainability of products and operations.” I will explain the significance of the phrases I’ve put in boldface in the next subsection. ChemRisk even highlights on their website a case where their meta-analysis established an “increased risk of lung cancer mortality associated with hexavalent chromium exposure.” But more often they enter the battle to reduce the risk to the companies that hire them. They are one of the firms that has been engaged in DuPont’s long battle over the risks from chemicals involved in Teflon production. Their studies have suggested a high threshold for silica-induced cancer risk and for asbestos exposures.

In seeking to expand his company’s business, the ChemRisk leader Dennis Paustenbach clarified the company’s goals in a letter to a Ford Motor Company attorney, quoted in The Triumph of Doubt: “Over the past 5 years, I have personally spent (in hard or soft dollars) a little more than $3M in profits (which would have been distributed to me or my staff) in asbestos-related research which has been enormously illuminating to the courts and juries. I did this because I believe that the courts deserve to have all the scientific information that can be brought to the table when reaching conclusions. In my view, these papers have changed the scientific playing field in the courtroom. You know better than anyone as you have seen the number of plaintiff verdicts decrease and the cost of settlement go down.”

Another product defense organization worth highlighting is the non-profit TERA (Toxicology Excellence for Risk Assessment), established by Michael Dourson in 1995. The TERA website claims that: “TERA solves human health risk challenges for diverse government and private sponsors through collaboration that emphasizes partnership building across scientific expertise and multiple perspectives to ensure the use of the best science… Independence from all parties and groups is essential in order for our science and results to be seen as credible by all parties… We are continuously vigilant to make sure that we remain open to new ideas, but we are not swayed or influenced by our funding sponsors, or any other party, in reaching our conclusions or communicating our results.” (I have added the boldface emphases.)

In contrast to that lofty claim of independence, David Michaels describes Dourson’s modus operandi as follows: “With funding in hand from a firm or an industry producing a product under scrutiny, his TERA team reviews the studies and produces a risk assessment that almost without exception minimizes the risk, pinpointing a level for ‘safe’ exposure that is almost without exception many times higher than the risk assessment level determined by academic or government scientists. Sometimes TERA’s risk assessment is provided by a panel of ‘independent’ experts, many of whom are not actually independent. The work is presented as legitimate science and often published in one of the industry-controlled journals…” This assessment captures what TERA means by “partnership building.”

Dourson has applied that approach prominently in producing a grossly misleading “safe exposure” limit for PFOA (a subclass of PFAS used in producing DuPont’s Teflon) in drinking water in West Virginia, a case we will explore in more detail in Part II of this post. But he has also applied it to contamination standards for the solvents trichloroethylene and 1,4-dioxane, to the pesticide Chlorpyrifos (for Dow AgroSciences), to petroleum coke (for Koch Industries), to the flame retardant tetrabromobisphenol A (for North American Flame Retardant Alliance), and to the food additive diacetyl (for a whole host of food producers). Predictably, TERA’s “independent” analyses always found the producers of these substances blameless, while proposing that exposure was safe up to levels as much as several thousand times the limits suggested by EPA or other regulatory agencies.

And how has TERA done in realizing its goal to produce results “seen as credible by all parties”? Not so well. Donald Trump nominated Dourson in 2017 to serve as Assistant EPA Administrator for Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention. But the nomination had to be withdrawn after widespread opposition, including detailed questioning from Senators, especially about his PFOA study for West Virginia, in light of the more than 3500 lawsuits against DuPont then in process regarding the toxic drinking water exposure. (Those lawsuits were eventually settled when DuPont and its spin-off company Chemours agreed to pay $672 million to the plaintiffs.) Dourson achieved enough public recognition to merit a dedicated New York Times editorial strongly opposing his nomination to the EPA. Here is an excerpt from that editorial:

“Mr. Dourson is a scientist for hire. A toxicologist and a professor at the University of Cincinnati, he has a long history of consulting for chemical companies and conducting studies paid for with industry money. He frequently decided that the compounds he was evaluating were safe at exposure levels that are far more dangerous to public health than levels recommended by the E.P.A., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other agencies. His nomination is enthusiastically endorsed by the chemical industry. It horrifies environmental groups, public health advocates, firefighters and scientists and has inspired many letters in opposition to the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, which may vote as early as Wednesday.”

There are enough companies willing to spend enough money on product defense to keep several other high-profile consulting firms thriving, as well. The Weinberg Group specializes in helping biotech, medical device and pharmaceutical companies obtain FDA approval for their products. This portfolio has gotten them involved in fighting against second-hand smoke regulations, DuPont’s Teflon liabilities, and the carcinogenic labeling of talc products. The name of their parent company, the ProPharma Group, illuminates the likelihood of independence in their scientific analyses. ENVIRON, acquired by the Danish company Ramboll in 2014, has consulted for Georgia Pacific in their battles against asbestos exposure from their joint compound product, for Monsanto in their continuing Roundup battles, and for a company called Sterigenic regarding ethylene oxide release from their plant in Willowbrook, Illinois.

Innovative Science Solutions (ISS) was established in 2000 to provide scientific consulting to legal counsel to “defend toxic tort cases involving industrial chemicals, toxic metals, welding fumes, radiofrequency radiation, asbestos, silica, and many other potentially toxic exposures… Effectively tracking and identifying relevant scientific literature can be the key to success in a complex toxic tort case. ISS employs state-of-the-art information technology and skilled personnel to track, compile and characterize scientific literature critical to the alleged toxic exposure or injury. These studies, once identified, are then put into the appropriate litigation context for integration in the overall litigation strategy.” For example, David Schwartz of ISS has provided details of how they worked to refute expert testimony about a link between genital use of talc and ovarian cancer in lawsuits against Johnson & Johnson. They are providing similar expertise to attorneys defending hydraulic fracturing companies.

The Center for Regulatory Effectiveness was established by Jim Tozzi in 1996 “to provide Congress with independent analyses of agency regulations. From this initial organizing concept, CRE has grown into a nationally recognized clearinghouse for methods to improve the federal regulatory process.” What that means in practice, according to David Michaels, is “to limit regulation on its corporate clients.” Tozzi has pursued that goal, for example, in the regulatory battles over second-hand smoke, talc and dioxin. He has promoted the use of lawsuits and judicial review to gum up the works of regulatory agencies. And, as Michaels points out: “Tozzi was instrumental in advancing one of Big Tobacco’s signature efforts to tie the EPA’s hands, the Data Quality Act, which permits corporations to challenge and re-analyze the data used as the basis for formulating regulations.” As we will see in the following section, that effort has considerable influence on regulatory rollbacks the EPA is presently proposing within the Trump administration.

The Astroturf Meadow:

In order to bring more troops to bear in product defense, most of the affected industries have also followed consultant advice to fund their own front organizations to lobby on their behalf and support research whose results are guaranteed to be favorable to the industry. Early examples were the Sugar Research Foundation established in the 1940s to “investigate charges that refined sugar is a primary cause of diabetes, tooth decay, polio, B vitamin deficiencies, obesity, mid-morning hypoglycemia, and many other conditions,” and the Tobacco Industry Research Committee established in 1954 by John Hill of Hill & Knowlton. As regulatory battles against the sugar and tobacco industries continued for decades, and defense strategies evolved, so did these front organizations. For example, in 2014 the Coca-Cola Company established and funded the non-profit Global Energy Balance Network, with the slogan “Healthier living through the science of energy balance,” to divert public attention away from sugar consumption and toward lack of exercise as causes of obesity and diabetes.

The tobacco company Phillip Morris, with advice and organization from the crisis management consultancy APCO Worldwide, established The Advancement of Sound Science Coalition (TASSC) in 1993, to discredit a 1992 EPA report that identified second-hand smoke as a confirmed human carcinogen, to fight against anti-smoking legislation, and to proactively pass legislation favorable to the tobacco industry. TASSC innovated in a couple of ways. It started the trend to name these front and astroturf organizations in ways that made them sound like defenders of scientific integrity. And it soon broadened its scope to oppose “over-regulation” across many industries, in order to obfuscate the primary funding source and focus from the tobacco industry.

Other examples of front organizations with misleading names include the American Council for Science and Health, an industry-funded organization that has systematically downplayed the risk of health hazards from products such as sugar, alcoholic beverages, PFAS, diesel exhaust, mercury emissions from coal-burning plants, and greenhouse gases. The Responsible Science Policy Coalition appears to have been formed in 2018 by 3M, Johnson Controls and unnamed other companies for the express purpose of helping western states avoid lawsuits regarding PFAS contamination of drinking water. The organization Conservation of Clean Air and Water in Europe (CONCAWE) is a trade association of European oil companies. The European Research Group for the Environment and Health in the Transport Sector (EUGT) was a collaboration of European auto and engine manufacturers that was dissolved under a cloud of outrage, as we discuss later in this post. The American Pain Foundation and the American Academy of Pain Medicine have advocated strongly on behalf of Big Pharma for liberalized opioid usage.

The International Life Sciences Institute is funded by hundreds of food and pesticide producers and does, in turn, fund genuine academic research on human health and the environment, but it also has carried water for its sponsors, for example, by questioning the quality of science underlying dietary guidelines on sugar intake. Similarly, the Alcoholic Beverage Medical Research Foundation (ABMRF) funds some legitimate research, but promotes its sponsors’ claim that alcohol consumed in moderation extends life expectancy. The International Climate Science Coalition works to undermine climate science, with funding, among others, from Koch Industries. In fact, Koch Industries and Big Tobacco are the two main funders of an entire network of astroturf anti-regulatory, anti-tax, Tea Party-correlated, organizations, a fraction of which are mapped in Fig. 4. These organizations work in concert to defend products that are harmful to public health and the global environment, often under the guise of defending consumer freedom.

There are also many trade organizations with more straightforward or neutral-sounding titles that defend the products of their funders against encroaching regulations or just bad publicity. The risk of exposure to toxic chemicals is downplayed by the American Chemistry Council. The Silica Coalition was established in 1997 by construction company trade groups seeking to forestall a strengthening of OSHA’s standards affecting worker exposure to crystalline silica dust. The American Petroleum Institute lobbies to reduce standards for noxious emissions from oil and gas processing. The NFL established a Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee for the express purpose of discrediting researchers who claimed that brain injuries to players were permanent and severe. The Personal Care Products Council (formerly, the Cosmetic, Toiletry and Fragrance Association) has worked with Jim Tozzi of The Center for Regulatory Effectiveness to successfully undermine federal labeling of talc containing asbestos-like fibers as a likely carcinogen. The CO2 Coalition and the Center for the Study of Carbon Dioxide and Global Change both use support from fossil fuel companies to argue, in opposition to the weight of scientific evidence, that increasing levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide will have primarily beneficial effects on the global environment. The list goes on.

The Industry-Supported Journals:

The product defense consultants and the trade associations need the imprimatur of scientific peer review in order for their pseudoscientific doubts cast upon epidemiological studies to be taken seriously by regulatory agencies and juries. The two journals most friendly to industry-funded research are Critical Reviews in Toxicology and Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. The editorial boards of both journals are stacked with industry-employed scientists and lawyers, together with some representatives of the product defense consulting firms.

Critical Reviews was established in 1971 by Leon Golberg, with The Chemical Rubber Company as publisher. Golberg was a toxicologist closely allied with industry throughout his career. In 1938 he had co-created a synthetic hormone (DES) used by pregnant women to combat morning sickness and prevent miscarriages. By 1971 DES had been linked to a rare vaginal cancer and other fertility problems, spawning many lawsuits and leading the FDA to issue a warning against its use. Golberg then wrote in its initial issue that Critical Reviews was being introduced as “the voice of reason” in an era of “chaos and turmoil. Never before have so many regulatory actions been taken or proposed – some too late, others prematurely – that have bewildered the consumer and had a crushing impact on industry.” Golberg also founded the now defunct Chemical Industry Institute of Toxicology, with major funding from the American Chemistry Council. He consulted for tobacco companies in the 1970s. Somewhat ironically, as chief editor of a journal that published numerous articles downplaying any health risks of asbestos exposure, Golberg died in 1987 of mesothelioma.

After Golberg’s death, editorship of Critical Reviews was taken over by veterinarian Roger McClellan, a longtime opponent of government regulation. The journal has a reputation not only of publishing many of the product defense industry’s misleading refutations of epidemiological studies, but also of having a rather laissez-faire attitude toward disclosure of its authors’ funding sources and conflicts of interest. For example, the authors of a 2013 article downplaying risks of asbestos exposure failed to clarify that they were paid nearly $180,000 in writing fees by an industry group, a detail that was only divulged in a subsequent court case. Another court case revealed internal Monsanto emails that showed the company working with an outside consulting firm to induce Critical Reviews to publish a 2016 purported “independent review” vindicating the safety of Monsanto’s Roundup herbicide, a review in fact ghostwritten with the help of Monsanto employees.

Regulatory Toxicology was launched in 1981 with the promise to focus on science rather than politics or “mythology.” It is the official publication of the International Society of Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology (ISRTP), a group whose leaders include a Coca-Cola executive, corporate consultants and lawyers, and a President who also heads the Council of Producers & Distributors of Agrotechnology. In response to questioning about industry financial support for the ISRTP, its previous President wrote, not very convincingly, in 2008 that “Science has an objective means of evaluating information, but it has nothing to do with who got the money and why.” (In a case study to be discussed below, we will see that nothing could be further from the truth. If industry pays for research, it will not allow the results to be published unless they support the industry’s point of view.)

One of Regulatory Toxicology’s original co-editors, AIDS researcher Frederick Coulston, told a Wall Street Journal interviewer in 1997 that nicotine wasn’t addictive and that smoking did not cause cancer. So much for focusing on science as opposed to politics and mythology. After Coulston’s death in 2003, the editorship was taken over by Gio Gori, a former Deputy Director of the National Cancer Institute, where he directed the Smoking and Health and the Diet and Cancer Programs. Gori subsequently made millions by directing the Franklin Institute Policy Analysis Center, a consulting firm largely funded by Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation, and arguing on behalf of the tobacco industry that the EPA had used “junk science” to distort the health effects of second-hand smoke. “Junk science” is a standard trope of the science denial industry.

In 2013, Gori and 17 other toxicology journal editors wrote an editorial criticizing the European Union’s plans to regulate endocrine disruptors, claiming that the recommendation defied “common sense, well-established science and risk assessment principles.” Only one of the 18 co-signing editors did not have industry ties. Industry-funded editors are unlikely to retain their funding if they reject articles pushed (sometimes ghost-written) by industry to rebut actually independent research that threatens their bottom lines, or if they turn down articles that label regulations as based on “junk science.”

Why do articles published in journals pushing an agenda, rather than independent science, get taken seriously in regulatory policy making? As the Center for Public Integrity reports: “representatives of the EPA, the FDA and the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration said their agencies treat science equally, regardless of the funding source. Disclosure is encouraged by all three agencies but isn’t mandatory.” This vast product defense network exists to throw lots of sand into the gears of drafting regulatory policy. As Arthur Caplan, founding Director of the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Langone Medical Center has pointed out: “The system can’t manage all that noise. The science tends to get lost and the politics wins or the economics wins. When there’s that much noise going on, other factors start to resolve the dispute and they’re not factual.”

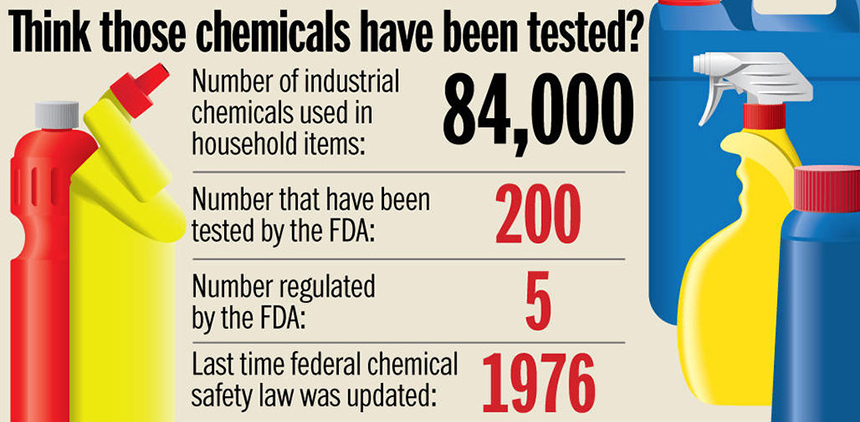

Evidence that the sand in the gears works is shown in Fig. 5. Gradient and other consulting firms used by the chemical industry not only write a lot of biased and scientifically shoddy articles that regulators have to take into account, but they also comment prolifically on proposed regulatory changes, either in writing or in person at public hearings. The agencies are then required to address each comment to the satisfaction of courts, and often also to survive lawsuits, before a new regulation can be put into effect. The product defense experts lobby Congress and often enlist Republican legislators to get the regulatory agencies to redo dozens of reviews of toxic chemicals. The net result is that among some 84,000 chemicals available for commercial use, the EPA has succeeded over more than 30 years to fully assess the health risks of only 570 of them. And as shown in Fig. 5, the assessments have been grinding to a halt, even during the Obama administration, which was reasonably committed to regulations to protect public health. Without a completed assessment, the Agency cannot even propose a regulatory exposure standard for a chemical. The cartoon of Fig. 6 reflects the current situation.

The Revolving Door Effect:

To make matters worse, there is a sometimes incestuous relationship between the regulatory agencies and the product defense network. For example, a former EPA employee, Lorenz Rhomberg, is now employed by Gradient Corporation, where he writes articles casting doubt on health hazards posed by the industries that hire Gradient. But Rhomberg also sits on a panel that reviews all of EPA’s toxic chemical assessments before they become final, so that he can gum up the works more effectively.

Such migration back and forth between industry groups and funding and the federal regulatory and research oversight agencies is common. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) is a center within the National Institutes of Health that funds research on the health impacts of alcohol consumption. But its current Director received research funding from the industry’s front organization ABMRF before assuming his present position. Its previous Acting Director went on to serve as a scientific advisor to Anheuser-Busch. And its past Director of the Division of Metabolism and Health Effects took on a leadership role within the trade association Distilled Spirits Council of the U.S. (DISCUS) after retiring from NIAAA.

It is then not surprising that several years ago, NIAAA invited giants of the alcoholic beverage industry to provide most of the funding for a massive, randomized clinical trial studying links between Moderate Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health (MACH). However, documents subsequently obtained by the New York Times under the Freedom of Information Act revealed that the project’s designers had its results predetermined, including one of them advertising beforehand that it provided “a unique opportunity to show that moderate alcohol consumption is safe and lowers risk of common diseases.” In initial response to the Times’ investigation, the NIAAA Director claimed that “Whoever donates to that fund has no leverage whatsoever – no contribution to the study, no input to the study, no say whatsoever.” Not long after he made that statement, NIH was forced to terminate the trial, admitting that “significant process irregularities in the development of the funding opportunities for the MACH funding awards undermined the integrity of the research process.”

The sometimes too-cozy relationship between regulators and product defenders is further illustrated by April 2019 reporting about Monsanto’s continuing efforts to avoid having its signature Roundup herbicide labeled as carcinogenic. The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) did, indeed, label Roundup’s central chemical glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans” in 2015. In contrast, the U.S. EPA decided, after strong lobbying by Monsanto and product defense teams, and in opposition to recommendations from the EPA’s own Science Office and one of its Science Advisory Panels, to say it was “not likely to be carcinogenic to humans.” However, a different U.S. health organization, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) within the Department of Health and Human Services was independently researching the extensive literature to determine glyphosate’s toxicity. “According to documents made public during court proceedings, the EPA Pesticide Office worked with Monsanto to hold back this ATSDR report for several years while it promoted its “no cancer risk” position…now-retired EPA Pesticide Office official, Jess Rowland told Monsanto’s Dan Jenkins, “If I can kill this I should get a medal”, according to internal Monsanto emails that have now been made public.”

A current EPA official from the pesticide office, Mary Manibusan, also got involved in coordinating with Monsanto. Manibusan worked at EPA for many years, followed by two years in the product defense industry with Exponent, and has returned to EPA as a Division Director in the Trump administration. While working at Exponent, she “was asked by Monsanto if she knew anyone at ATSDR working on chemical tox profiles. ‘Sweetheart, I know lots of people so you can count on me,’ Manibusan told Monsanto’s Jenkins, who said, ‘We’re trying to do everything we can from having a domestic IARC occur with this group. May need your help…’“ Despite the Pesticide Office’s best attempts, it was unable to prevent the 2019 release of the ATSDR draft report, whose findings supported the IARC labeling of glyphosate. The EPA has not, however, altered its determination that glyphosate is “not likely to be carcinogenic to humans.” We will reveal more aspects of the lengthy Roundup saga in Part II of this post.

III. Epidemiology-Busting Techniques

Epidemiological studies of potential health hazards of commercial products are highly non-trivial undertakings. Large subject samples are needed to obtain statistically meaningful results. The cohort of subjects who have been exposed to the product must be chosen randomly to be representative of the larger population of exposed individuals. The level of their exposure, which often took place years before the study, must be determined with an acceptable accuracy. A similarly large control group, with similar age and demographic distributions, but no or much less exposure to the product, must also be chosen randomly. Members of the cohort and members of the control group will generally have other conditions, other behaviors, and exposures to other products or environmental pollutants that influence their susceptibility to the disease under study. The analysis of the results must take these confounding variables into account, and correct for them with well-understood uncertainties. Errors in any of these steps, including possibly inadvertent sample selection bias, can compromise the results. It is thus essential that any conclusions drawn regarding toxicity be based on the preponderance of evidence from multiple, independent studies linking the same product to the same disease outcome. But differences in the results among multiple studies open numerous avenues for the epidemiology-busters to exploit, especially when the biomolecular mechanisms for toxicity are not well understood.

The large-sample studies are sometimes supplemented with experiments investigating disease outcomes for animals subjected to larger and shorter-term exposures to the same chemicals. But there are also ambiguities in interpreting such animal study results, including calibration of the animal exposure against longer-term human exposures and biological extrapolation from animal impacts to human impacts.

Industries combating epidemiological studies indicating product toxicity and imminent regulatory actions are seldom willing to invest the time to carry out their own analogous long-term epidemiological research. (Of course, in some cases eventual litigation discovery uncovers internal documents revealing that the industries did previously carry out such research, but hid any negative results from the public.) The focus, then, of product defense is typically on poking holes in the existing research database, and finding ways to favor studies that produce negative toxicity risks over those that find positive disease correlations. There are several techniques used by the product defense scientists, with their industrial clients generally preferring the ones that involve the least cost and time investment. We review some of these techniques briefly here, with more detail and more examples of each covered in The Triumph of Doubt.

Weight of the Evidence:

The simplest of the techniques are “weight of the evidence” reviews. These are basically opinionated literature reviews. When undertaken by a product defense consulting team, they invariably find flaws in all previous studies that suggested any risk from the client’s product, while promoting studies that suggest toxic impacts occur only at exposures far beyond what the client’s product provides. When they are unable to convincingly cast doubt on all studies showing significant risk, the weight-of-the-evidence reviews typically conclude that the science is unsettled and more studies are needed. In other words, they buy time for the product developers to reap more profits.

The Gradient Corporation specializes in weight-of-the-evidence reviews. They have, for example, produced such reviews about links between ozone emissions and asthma severity for the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) – a state government agency that works assiduously to protect the oil and gas industry – and for a trade association representing electric power companies. Their reviews are published in two papers, entitled “Short-Term Ozone Exposure and Asthma Severity: Weight-of-Evidence Analysis” and “Critical Review of Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Asthma Development,” reaching similar conclusions: the evidence “is not sufficient to conclude that a causal relationship exists. The substantial uncertainty in the body of evidence should be taken into consideration when this evidence is used for policymaking.”

Gradient played a similar role in considerations of lead poisoning impacts on children’s neurological development. As Michaels reports: “When EPA was tightening its environmental lead standard during the Clinton administration, Gradient experts went to the White House on behalf of the Association of Battery Recyclers. Its presentation highlighted ‘unresolved potential math errors’ and the uncertainties in the scientific literature used by EPA to justify the stronger standard.” Pinning your case on “potential math errors” is a pretty weak argument.

In yet another example, Gradient scientists helped to persuade the FDA to declare that the ubiquitous chemical bisphenol A (BPA) – present in canned goods and plastic bottles – was harmless, despite hundreds of articles by academic scientists linking BPA exposure to infertility, diabetes, cancer and heart disease. Gradient’s weight-of-the-evidence review argued that humans are exposed to far less BPA than animals that developed reproductive problems in dozens of laboratory tests. Frederick vom Saal, a University of Missouri professor who has investigated BPA for more than two decades, called that argument “complete nonsense…You create a false statement of fact, and then you discount a whole literature…In this article, there is nothing that is true. It’s ridiculous. And that’s how they operate.” A group of academic experts on BPA toxicity wrote a rebuttal to the Gradient article, including a table that listed all of the “false statements” in the Gradient review. Yet that review created enough uncertainty to influence the FDA decision strongly.

Risk Assessment:

Another preferred method for epidemiology-busting is to argue, often without much quantitative justification, that health risks become significant only at exposure levels far beyond those provided by the client’s product. A leading practitioner of such phony risk assessments is Michael Dourson of TERA.

In an example we will explore in more detail in Part II of this post, Dourson and his allegedly “independent” team of scientists, in response to anticipated lawsuits from West Virginia citizens and possible EPA action, convinced the state government of West Virginia in 2002 that exposure to the PFOA used in producing DuPont’s Teflon was perfectly safe up to contaminant levels of 150 parts per billion in drinking water. TERA had been recommended for this assessment to the state government by DuPont, which at that time had an internal safety limit for its own employees of only one part per billion (ppb). The EPA would eventually (2016) set a national drinking water health advisory level for PFOA at 0.07 ppb, and various states have set even lower safety limits. During the many DuPont lawsuits, attorneys attempting to determine just how the TERA team had arrived at the 150 ppb number were unable to obtain notes from the meetings that produced that result; those notes appear to have been shredded by the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection. Drinking water contaminant levels from the PFAS family of “forever chemicals” – a class, of which PFOA is one example, with known links to cancer and immune system damage among other health hazards – remain a forefront issue to this day at many locations throughout the U.S.

The PFOA example is hardly an outlier for Dourson and TERA. They also recommended a safe level for 1,4-dioxane – a labeled “likely carcinogen” — that was 1000 times higher than EPA’s recommended safe level. Dourson recently advised the states of Missouri and Indiana that the safe exposure limit for trichloroethylene should be 15 times higher than EPA’s recommendation, without divulging to the states that his study on this topic had originally been funded by the American Chemistry Council trade organization.

Chlorpyrifos is a widely used insecticide developed by Dow AgroSciences, which has been found to adversely affect children’s brain and nervous system development even at low doses. Based on the preponderance of epidemiological evidence, EPA scientists have recommended that children between the ages of 1 and 2 not be allowed in their food intake to consume more than 0.0017 micrograms of chlorpyrifos per kilogram of body mass per day. However, in a 2006 study funded by Dow AgroSciences, Dourson suggested that kids could safely consume up to 10 micrograms per kilogram of body mass per day, a limit about 6000 times higher than EPA’s suggestion. Based on his performance on behalf of industrial sponsors, the American Chemistry Council and other trade organizations funded TERA to mount the website kidschemicalsafety.org, dedicated to downplaying the risks of toxic chemical exposure to children. Many more cases of Dourson’s industry-funded risk assessments are revealed on this website.

Reanalysis:

One of the most cost-effective ways – first promoted during the Big Tobacco battles – for product defense scientists to rebut what their industrial sponsors view as threatening epidemiological studies is the insistence on reanalyzing the raw data from the study. Given the complexities of epidemiology outlined briefly at the start of this section, it is imperative for scientists to lay out the principles and methods of their intended analysis before they begin to analyze the collected data, in order to minimize any bias that might creep into the results. Epidemiology-busters feel no such restrictions when they perform post hoc reanalyses of the same data, applying their own models and assumptions devised specifically to deny the original conclusions. As David Michaels explains: “If a scientist with a certain skill set knows the original outcome and how the data are distributed within the study, it’s easy enough to design an alternative analysis that will make positive results disappear.”

As an example, Michaels lists 9 papers written by product defense scientists from Exponent, ChemRisk, Ramboll ENVIRON, and Gradient, all attempting to reanalyze data from a 1987 study revealing increased risk of leukemia from lifetime benzene exposures below one part per million. That level was an order of magnitude below the then-current workplace standard that had been established by OSHA, and it thus threatened oil industry profits. The reanalyses were funded by the American Petroleum Institute and other oil industry representatives. In this case, however, those reanalyses have been refuted by independent new epidemiological studies that reinforce and strengthen the conclusions from the 1987 study. In response, the European Union is planning to reduce the workplace exposure limit to 0.05 parts per million.

Because reanalyses are so cost-effective, the purveyors of toxic products have enlisted help from friendly Congress members and, under the Trump administration, even from EPA itself, to ensure their access to the raw data that instructs their defenders how to construct the post hoc analyses to rebut the original findings. They have been frustrated, and lobbied against what they labeled “secret science,” when those data have not been available. The tobacco industry, led by Phillip Morris, orchestrated the drafting of legislation during the battle over second-hand smoke. A particularly influential, large epidemiological study had been carried out with funding from the National Cancer Institute in the 1980s under the leadership of Elizabeth Fontham of Louisiana State University. The results of that study showed that the risk of contracting lung cancer increased by 30% among non-smoking wives of male smokers, and by 40-60% among those exposed to second-hand smoke in workplaces and other locations outside the home. These results were potentially devastating to the tobacco industry, which had by then long been promoting consumer freedom and individual choice as fundamental protections for smokers’ rights.

However, Fontham refused to release the raw data, with its private medical information about many individuals, for reanalysis by tobacco defenders. In the light of her refusal, the tobacco industry enlisted the help of Sen. Richard Shelby of Alabama to pass the Data Access Act as a four-line amendment to the 1999 Omnibus Appropriations Act. The Data Access Act requires all federally supported researchers at non-profit institutions (thereby exempting corporate research!) to give up their raw data, when requested via the Freedom of Information Act, subject to some protections for personal information, confidential business information or information that could pose a security risk. They furthermore succeeded, with the help of Jim Tozzi of The Center for Regulatory Effectiveness, in getting another amendment to a spending bill passed in 2001, now known as the Data Quality Act, which grants corporations the right to challenge and reanalyze the data used as a basis for formulating federal regulations.

In these legislative maneuvers, Big Tobacco received support from, and often hid behind, oil companies and coal-burning electrical utilities who were upset by a different epidemiological study regarding the health hazards of their emissions of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) into the atmosphere. The Harvard Six Cities Study had found that residents in Steubenville, Ohio – the city they studied with the highest air pollution – had an overall mortality risk, including from lung cancer and cardiopulmonary disease, 25% higher than residents in the least polluted of their focus cities (Portage, Wisconsin). Again, the private health data of the 8,111 Americans who participated in the Six Cities Study were kept confidential, to the consternation of industry. That research was influential in leading to Congressional passage of the 1997 revisions to the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS).

The battle over public access to raw data continues to this day. In response to numerous complaints from scientists and research institutions, the Office of Management and Budget under President Clinton chose to interpret the four lines of the Data Access Act narrowly, as “limiting requested data to published or cited research used in developing legally binding agency actions.” The fight resumed when Congressman Lamar Smith, Republican of Texas, assumed chairmanship of the House of Representatives Science Committee in 2013. Seeking to protect his fossil-fuel benefactors, Smith tried several times to introduce the so-called Secret Science Reform Act, which would have forbidden EPA from using any study in its regulatory decisions unless the authors submitted all raw data, computer programs and analysis tools used, to be published on the internet, so as to facilitate industry reanalyses (see Fig. 7).

The Secret Science Reform Act never passed both houses of Congress, and Lamar Smith has now retired, but under the leadership of Scott Pruitt and Andrew Wheeler the EPA itself has taken up the fight. They have proposed in 2018, and again in 2020, the misleadingly titled “Strengthening Transparency in Regulatory Science” rule, which we have commented on in detail elsewhere on this site. That rule, which has yet to pass muster via court review, would make the ability to reanalyze raw or nearly raw data, regardless of privacy concerns about personal health information, a paramount consideration in deciding which research could be taken into account in EPA discussions of health hazards and regulations. Furthermore, it would grant the EPA Administrator the authority to waive the requirement whenever he/she sees fit. This would be a boon to the product defense industry and would, in fact, decrease transparency in regulatory science.

Truly independent scientists understand that the fundamental criterion for research results to be taken seriously is the ability to replicate the results in independent studies carried out by independent teams using independent methods. The narrow focus on reanalyzing data taken by someone else makes sense only when you want to cast doubt on those results without committing the time and resources to carry out your own independent study. David Michaels quotes Bernard Goldstein, Associate EPA Administrator under President Reagan, explaining that “reanalyzing the same study over and over is about as useful as checking on a surprising newspaper article by buying additional copies of the same paper to see if they all say the same thing.” But when you get to reinvent the rules of the analysis after seeing what the data show in granular detail, it does provide a cheap way to manufacture doubt.

Back-In-Time Simulations:

Product defense scientists will sometimes utilize simulations in an attempt to demonstrate that historical exposure levels estimated in earlier epidemiological studies were grossly in error. The sign of the error varies according to the need of the industry funding the work. If federal agencies are formulating regulations based on the historical studies, then the simulations will attempt to prove that the historical exposures were much higher than originally estimated, so that exposure standards should be set at a high level, well above the exposures that the industry’s “new, improved” products present.

However, if a company is being sued as a result of health deterioration blamed on past exposures to their product, then they want the simulations to demonstrate that the plaintiff was, in fact, subjected to much lower exposures than claimed (but possibly to large exposures of different manufacturer’s products that may well have caused the plaintiff’s ailment). ChemRisk is a prime user of the simulation strategy. They used it, for example, to exonerate Union Carbide in a lawsuit based on asbestos exposures from machining the company’s Bakelite plastic. They used their simulation results to convince a court that historical airborne asbestos concentrations from reasonable work with Bakelite were well under exposure safety limits, while ignoring actual asbestos measurements made in the 1970s. ChemRisk’s Dennis Paustenbach has bragged: “I’m not aware of a single case that has been lost in litigation in the U.S. when a high-quality simulation study was done.”

Claiming That New, Improved Products Have Solved Old Problems:

Since epidemiological studies generally consider health records assembled over many years, product producers and defenders can sometimes try to claim that recent technological improvements have already solved the acknowledged old toxicity problem, and have rendered the old studies obsolete. In such an attempt, it becomes essential to find ways to demonstrate that the new products have indeed reduced toxicity. The most egregious, distasteful and embarrassing example of attempts to provide such evidence is associated with Volkswagen’s (VW) marketing of their new diesel engines over the past decade. It is an episode that illuminates why most in the product defense industry prefer to focus on poking holes in others’ research, as opposed to taking on the risks involved in commissioning new research, especially with laboratory animals.

VW was intent on increasing its worldwide automobile market share by dominating the diesel engine sector. In Europe, where fuel is taxed heavily, diesel fuel was taxed significantly less than gasoline, because the diesel fuel burns more efficiently, emits less carbon dioxide, and therefore contributes less to global warming. What the diesel fumes do contain, however, is far more fine particulate matter and nitrogen oxides, which are known to cause respiratory infections, asthma, heart attacks and cancer, while also contributing to acid rain. The EPA, and particularly the California Air Resources Board, had placed strict limits on nitrogen oxide emissions. In a well-covered scandal that has come to be known as Dieselgate, VW decided to “demonstrate” that its new engines could pass these strict American standards by cheating. In order to keep the cost of their diesel cars down, they installed traps for nitrogen oxides that could not last long, and which therefore were activated only when installed software sensed that the car was undergoing emissions testing – when it was operating on rollers, with no turning of the steering wheel.

By marketing their new diesel engines as both green and efficient, with excellent gas mileage, VW sales contributed to a six-fold increase between 2007 and 2013 in diesel-powered passenger vehicle sales within the U.S., where diesel fuel did not benefit from the tax subsidy in European countries. By 2016, VW had surpassed Toyota as the number one auto manufacturer in the world. They might have gotten away with their cheating for a much longer time if they had not raised suspicions by lobbying hard against a move to increase the stringency of the then still-loose European Union limits on nitrogen oxide emissions. Why would they do that if they had already solved the problem? Then it was discovered in 2014 that VWs sold in Europe did not come close to meeting the California standards. The scandal came to a head in 2015, and after much prevarication by VW managers, it led to arrests of some of them, to more than $30 billion of penalties for VW, and to their buyback of 400,000 cars from U.S. customers. This much of the scandal was subject to worldwide news coverage and a complete account in Jack Ewing’s book Faster, Higher, Farther: The Volkswagen Scandal.

The less well-known part of the scandal concerns product defense research overseen by the industry front group EUGT that was set up in 2007 by VW, BMW, Daimler and the German engine manufacturer Bosch. This group used the standard tools of epidemiology-busting outlined above to downplay cancer risks from diesel exhaust. In 2012, they fought against an imminent IARC classification of diesel particulates as a known human carcinogen, by claiming that the carcinogenic exhaust was only from the older diesel engines, not the new improved engines that were then being marketed by VW and others. They could not afford the time to undertake a new, lengthy epidemiological study. So instead, they decided with VW to commission a new animal study that would demonstrate how much cleaner the exhaust was from the new, compared to older, diesel engines.

The EUGT established a contract with the Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute, a private, New Mexico non-profit laboratory, to carry out an experiment exposing groups of ten macaque monkeys to exhaust from the diesel engines of a 1997 Ford F-250 pickup truck and from a new diesel VW “Beetle.” Jack Ewing paints the disturbing picture (see Fig. 8): “In 2014…in an Albuquerque laboratory…Ten monkeys squatted in airtight chambers, watching cartoons for entertainment as they inhaled fumes from a diesel Volkswagen Beetle.” The emissions from each engine were fed into the monkeys’ chambers diluted with filtered air. For control purposes, some of the monkeys were exposed only to the old engine’s exhaust, some to the new engine’s exhaust, and some only to the filtered air. Medical exams administered to each monkey after each exposure focused on evidence of lung inflammation.

In order to reduce their risk of getting results they would not like, VW and EUGT used a Beetle engine with the cheat device to reduce nitrogen oxide emissions activated, although they failed to divulge that to the Lovelace scientists. In the end, that ethical failure – only one of many committed by VW and EUGT – did not matter, as divulged via discovery documents revealed in later lawsuits against VW. The initial Lovelace results showed more lung inflammation in the monkeys exposed to the VW Beetle’s exhaust than in those exposed to the Ford F-250 exhaust, despite the fact that nitrogen oxide emissions should have been much lower for the Beetle.

In 2015, when the Dieselgate scandal broke, the Lovelace team learned along with everyone else that the VW exhaust had been rigged, and realized that they somehow had come up with the “wrong” experimental result. Despite the fact that the Lovelace scientists altered their paper draft to obfuscate, and subsequently even to cherry-pick the results, in an attempt to satisfy the EUGT overseers, EUGT was never satisfied. They blocked publication of the paper and never completed final payments to Lovelace, before the EUGT itself was dissolved in 2017, in the midst of the furor that broke out over Dieselgate and “Monkeygate.” Before that tragicomical ending, lead Lovelace researcher Jacob McDonald described some of the data acquired as “garbage” in an e-mail to a colleague, and put a deadpan spin on his own modest goals: “I am trying to see if I can squeeze out something else that may be interesting and says “old dieslel [sic] bad, new diesel good’ so I can win the Nobel Prize.”

The VW experience demonstrates vividly why the product defense network seldom engages in their own new research. In order to appreciate the multi-faceted approach they do take to toxic product defense, it is useful to consider some case studies in more detail. We will do that in Part II of this post for two recent and ongoing cases, where the discovery phase of multi-plaintiff lawsuits has revealed how much and how early the producers knew about their own product’s toxicity, and their extensive efforts to cover up and deny that knowledge over decades.

References:

David Michaels, The Triumph of Doubt: Dark Money and the Science of Deception, Oxford University Press, 2020, https://www.amazon.com/Triumph-Doubt-Money-Science-Deception/dp/0190922664

David Michaels, Doubt is Their Product: How Industry’s Assault on Science Threatens Your Health, Oxford University Press, 2008, https://www.amazon.com/Doubt-Their-Product-Industrys-Threatens/dp/019530067X

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Michaels_(epidemiologist)

David Heath, Meet the ‘Rented White Coats’ Who Defend Toxic Chemicals, https://publicintegrity.org/environment/meet-the-rented-white-coats-who-defend-toxic-chemicals/

2014 Surgeon General’s Report: The Health Consequences of Smoking – 50 Years of Progress, https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/50th-anniversary/index.htm

T. Remen, J. Pintos, M. Abrahamowicz and J. Siematycki, Risk of Lung Cancer in Relation to Various Metrics of Smoking History: A Case-Control Study in Montreal, BMC Cancer 18, 1275 (2018), https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12885-018-5144-5#Abs1

https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-toxic-substances-control-act

https://www.madesafe.org/science/hazard-list/

https://www.hkstrategies.com/specialist-expertise/issues-crisis/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hill%2BKnowlton_Strategies

https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/tobacco-industry-research-committee/

L. Savan, Teflon is Forever, Mother Jones, May/June 2007, https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2007/05/teflon-forever/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scotchgard

https://www.drugwatch.com/vioxx/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silicon_dioxide

https://www.webmd.com/lung/what-is-silicosis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asbestos

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lead_poisoning

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vinyl_chloride

https://debunkingdenial.com/scientific-tipping-points-the-ozone-layer/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dioxins_and_dioxin-like_compounds

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berylliosis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydraulic_fracturing

https://debunkingdenial.com/s-fred-singer-all-purpose-science-denier/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passive_smoking

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glyphosate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roundup_(herbicide)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Per-_and_polyfluoroalkyl_substances

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diesel_exhaust

https://gradientcorp.com/services-overview.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bisphenol_A

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hexavalent_chromium

https://debunkingdenial.com/scientific-tipping-points-the-banning-of-ddt-part-i/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flame_retardant

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heavy_metals

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercury_(element)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_and_safety_hazards_of_nanomaterials

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitrogen_dioxide_poisoning

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ozone#Health_effects

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polychlorinated_biphenyl#Health_effects

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_effects_of_pesticides

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Total_petroleum_hydrocarbon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Particulate_pollution

J.J. Zou, Brokers of Junk Science?, https://publicintegrity.org/environment/brokers-of-junk-science/

https://www.cardnochemrisk.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=54&Itemid=5

https://www.tera.org/ART/index.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Dourson

N. Rich, The Lawyer Who Became DuPont’s Worst Nightmare, New York Times Magazine, Jan. 6, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/10/magazine/the-lawyer-who-became-duponts-worst-nightmare.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trichloroethylene#Physiological_effects

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1,4-Dioxane

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chlorpyrifos

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petroleum_coke#Health_hazards

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetrabromobisphenol_A

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diacetyl

J. Mordock, DuPont, Chemours to Pay $670 Million Over PFOA Suits, The News Journal, Feb. 13, 2017, https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2017/02/13/dupont-and-chemours-pay-670m-settle-pfoa-litigation/97842870/

The Editorial Board, Mr. Trump Outdoes Himself in Picking a Conflicted Regulator, New York Times, Oct. 17, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/17/opinion/mr-trump-outdoes-himself-in-picking-a-conflicted-regulator.html

https://weinberggroup.com/regulatory-strategy-submissions/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethylene_oxide#Physiological_effects

https://www.innovativescience.net/

https://www.thecre.com/regreview/index.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_Energy_Balance_Network

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advancement_of_Sound_Science_Center

National Center for Environmental Assessment, Respiratory Health Effects of Passive Smoking, https://web.archive.org/web/20100630140355/http:/cfpub2.epa.gov/ncea/cfm/recordisplay.cfm?deid=2835

https://debunkingdenial.com/profiles-in-denial-introduction/

M. Halpern, What Is the Responsible Science Policy Coalition?, https://blog.ucsusa.org/michael-halpern/what-is-the-responsible-science-policy-coalition-here-are-some-clues#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20PowerPoint%20presentation,about%20the%20dangers%20of%20PFAS.&text=detailing%20what%203M%20knew%20about%20the%20chemicals’%20harms.

https://www.grid.ac/institutes/grid.458392.1

C. Ornstein and T. Weber, American Pain Foundation Shuts Down as Senators Launch Investigations of Prescription Narcotics, ProPublica, May 8, 2012, https://www.propublica.org/article/senate-panel-investigates-drug-company-ties-to-pain-groups

J. Erickson, et al., The Scientific Basis of Guideline Recommendations on Sugar Intake: A Systematic Review, Annals of Internal Medicine 166, 257 (2017), https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M16-2020

https://www.climatescienceinternational.org/

A. Fallin, R. Grana and S.A. Glantz, ‘To Quarterback Behind the Scenes, Third Party Efforts: The Tobacco Industry and the Tea Party, Tobacco Control 23, 322 (2014), https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/tobaccocontrol/23/4/322.full.pdf

https://www.americanchemistry.com/About/

Construction Industry Fears Silica Proposal Cost, Industrial Safety and Hygiene News, Sept. 23, 2013, https://www.ishn.com/articles/96851-construction-industry-fears-silica-proposal-cost

Union of Concerned Scientists, The NFL Tried to Intimidate Scientists Studying the Link Between Pro Football and Traumatic Brain Injury, Oct. 11, 2017, https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/nfl-tried-intimidate-scientists-studying-link-between-pro-football-and-traumatic-brain

https://www.personalcarecouncil.org/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_Reviews_in_Toxicology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regulatory_Toxicology_and_Pharmacology

https://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/The_Chemical_Industry_Institute_of_Toxicology

R.O. McClellan, The Legacy of Leon Golberg, Toxicological Sciences 72, 188 (2003), https://academic.oup.com/toxsci/article/72/2/188/1691257

D. Bernstein, et al., Health Risk of Chrysotile Revisited, Critical Reviews of Toxicology 43, 154 (2013), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23346982/

Spinning Science and Silencing Scientists: A Case Study in How the Chemical Industry Attempts to Influence Science, Minority Staff Report of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space and Technology, February 2018, https://science.house.gov/imo/media/doc/02.06.18%20-%20Spinning%20Science%20and%20Silencing%20Scientists_0.pdf?1

http://www.isrtp.org/nonmembers/ISRTP%20May%202008%20Newsletter.pdf

G. Brooks, Stuck with Monkey on Its Back, Air Force Tackles a Hairy Issue, Wall Street Journal, Dec. 30, 1997, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB883434183761023000

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gio_Batta_Gori

G.B. Gori, Passive Smoke: The EPA’s Betrayal of Science and Policy, The Fraser Institute (1999), https://www.amazon.com/Passive-Smoke-Betrayal-Science-Policy/dp/088975196X

http://www.altex.ch/resources/open_letter.pdf

https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/endocrine/

https://med.nyu.edu/faculty/arthur-l-caplan

https://www.distilledspirits.org/

R.C. Rabin, Is Alcohol Good for You? An Industry-Backed Study Seeks Answers, New York Times, July 3, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/03/well/eat/alcohol-national-institutes-of-health-clinical-trial.html

R.C. Rabin, Federal Agency Courted Alcohol Industry to Fund Study on Benefits of Moderate Drinking, New York Times, March 17, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/17/health/nih-alcohol-study-liquor-industry.html

NIH to End Funding for Moderate Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health Trial, NIH News Release, June 15, 2018, https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-end-funding-moderate-alcohol-cardiovascular-health-trial

J. Sass, ATSDR Report Confirms Glyphosate Cancer Risks, https://www.nrdc.org/experts/jennifer-sass/atsdr-report-confirms-glyphosate-cancer-risks

Toxicological Profile for Glyphosate, ASTDR Draft Report, April 2019, https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp214.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confounding

J.E. Goodman, et al., Short-term Ozone Exposure and Asthma Severity: Weight-of-Evidence Analysis, Environmental Research 160, 391 (2018), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29059621/

K. Zu, et al., Critical Review of Long-term Ozone Exposure and Asthma Development, Inhalation Toxicology 30, 99 (2018), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29869579/

J.E. Goodman, et al., An Updated Weight of the Evidence Evaluation of Reproductive and Developmental Effects of Low Doses of Bisphenol A, Critical Reviews in Toxicology 36, 387 (2006), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16954066/

S. Lerner, Trump’s EPA Chemical Safety Nominee was in the “Business of Blessing” Pollution, The Intercept, July 21, 2017, https://theintercept.com/2017/07/21/trumps-epa-chemical-safety-nominee-was-in-the-business-of-blessing-pollution/

https://www.epa.gov/pfas/basic-information-pfas

A. Lustgarten, How the EPA and the Pentagon Downplayed a Growing Toxic Threat, ProPublica, July 9, 2018, https://www.oregonlive.com/today/2018/07/pentagon_epa_downplay_threat_o.html

A. Snider, Pentagon Recruits Rejected Scientist for Massive Pollution Fight, Politico, Jan. 13, 2019, https://www.politico.com/story/2019/01/13/pentagon-scientist-pollution-fight-1078023

S. Lerner, Protect Our Children’s Brains, New York Times, Feb. 3, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/03/opinion/sunday/protect-our-childrens-brains.html?_r=0-scraps-scheduled-ban-pesticide-harms-kids-brains#.WZ2Z25N95TY

Q. Zhao, M. Dourson and B. Gadagbui, A Review of the Reference Dose (RfD) for Chlorpyrifos, https://www.tera.org/Publications/CPFManuscriptRevision.pdf

https://web.archive.org/web/20160314033437/http:/kidschemicalsafety.org/

D. Andrews and M. Benesh, EWG Investigates: Mr. Pay to Spray, Michael Dourson, https://www.ewg.org/research/ewg-investigates-mr-pay-spray-michael-dourson

A. Baba, D.M. Cook, T.O. McGarity and L.A. Bero, Legislating “Sound Science”: The Role of the Tobacco Industry, American Journal of Public Health 95, S20 (2005), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16030333/#:~:text=The%20tobacco%20industry%20played%20a,health%20and%20regulatory%20policy%20decisions.

J.E. Brody, New Study Strongly Links Passive Smoking and Cancer, New York Times, Jan. 8, 1992, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/01/08/health/new-study-strongly-links-passive-smoking-and-cancer.html

https://nnlm.gov/data/thesaurus/data-access-act

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data_Quality_Act