August 11, 2025

III. flawed metrics

Given the steady flow of scientific progress outlined in Part I of this post, why have claims that science is “slowing down” been emerging over the last decade? Several recent articles have tried to quantify scientific disruption and have produced metrics that served to reinforce some commenters’ prejudices about scientific progress. Unfortunately, it is highly unlikely that those metrics tell a story about science slowing down. Let’s deal with the analyses one at a time.

Citation-based analyses:

In a 2023 paper entitled The Decline of Disruptive Science and Technology, published in the prestigious journal Nature, Park, Leahey, and Funk attempted to measure “disruptiveness” by using citation statistics for scientific papers and patents. Their analysis is based on their intuition that “if a paper or patent is disruptive, the subsequent work that cites it is less likely to also cite its predecessors…[since] the ideas that went into its production are less relevant…If a paper or patent is consolidating, subsequent work that cites it is also more likely to cite its predecessors…” This assumption seems based on Thomas Kuhn’s flawed concept of “incommensurability” between a paradigm-shifting work and the work that went before. Not all disruptive research changes a paradigm and not all paradigm shifts render earlier work irrelevant. The authors’ assumption is also questionable for other reasons; for example, scientific papers will often cite a review paper (hardly a disruptive source) and not cite the many references included in that review paper. But there are far more serious flaws in this analysis than these quibbles.

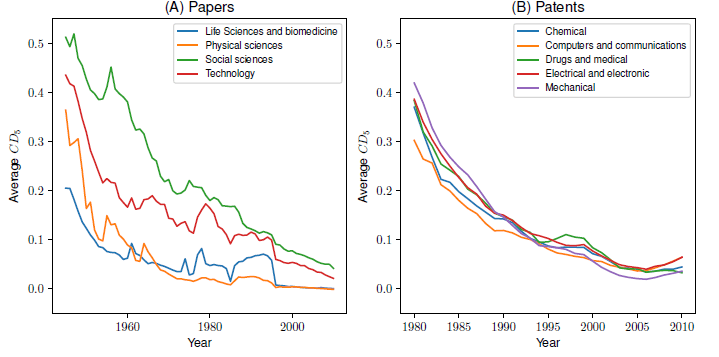

The metric defined in the paper, labeled CD5, basically represents the fraction of papers that come out five years after the paper being judged, which cite the paper being judged but none of the earlier citations contained within the paper being judged. The scale varies from -1 for a purely consolidating paper to +1 for a purely disruptive paper with none of the papers citing it also citing the original paper’s predecessors. The citation statistics are drawn from 25 million papers and all their citations contained within the Web of Science database from 1945 through 2010 and on 3.5 million patents contained within the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s database from 1976 through 2010. Figure III.1 shows the results the authors obtain for the average CD5 values for all papers and patents published in a given year, broken down by the field of the scientific papers and patents.

The authors claim that the results in Fig. III.1 show “that progress is slowing in several major fields of science and technology.” Their paper’s conclusions attracted worldwide media coverage, including in the New York Times (“What Happened to All of Science’s Big Breakthroughs?”), The Atlantic (“The Consolidation-Disruption Index is Alarming”), Forbes (“Where Are All the Scientific Breakthroughs? Forget AI, Nuclear Fusion, and mRNA Vaccines, Advances in Science and Tech Have Slowed, Major Study Says”), The Economist (“Papers and Patents are Becoming Less Disruptive”), the Financial Times (“Science is Losing its Ability to Disrupt”), El Pais, Le Monde, and many more. Unfortunately, when we look at these curves we come to an entirely different conclusion.

Consider the right-hand frame in Fig. III.1. When the curves for such disparate fields, at very different stages of maturity, basically fall on top of one another, this tells us that the curves represent some basic problem of the metric, with little to do with the disruptiveness of the fields in question. Indeed, the analysis contains a major blunder. Only citations within the time ranges indicated have been considered in the analysis. For papers published in 1945 or patents published in 1976 very few, possibly none, of the references cited within such work will be contained in the databases. It is then not at all surprising that later work that cites the original will most likely not cite its predecessors, simply because its predecessors are not included in the database. As time goes on from the earliest year in the databases, more and more of the earlier work is contained in the databases, hence, more and more of the later work cites both the paper to be judged and its own citations. Thus, all that the rapidly decreasing curves in Fig. III.1 tell us is that as the years pass, a progressively larger fraction of the citations included in a paper will be included in a database with a fixed start date.

We are not the first to remark on this rather obvious flaw. In 2024 Macher, Rutzer, and Weder included corrections for the enormous biases hidden in the patent analysis by Park, Leahey, and Funk. They consider the issue we raised above to be “truncation bias,” since predecessor work is truncated by the arbitrary start date chosen for the database. For patents only, they also consider an “exclusion bias” based on the fact that the earlier analysis did not take account of a change in U.S. patent law in 1999, which allowed subsequent patents to cite both earlier patent grants and earlier patent applications. But Park, Leahey, and Funk excluded all references to patent applications in patents published after 2000.

The ”money plot” from Macher, et al. is shown in Fig. III.2. Correction for truncation bias completely tames the rapid decline in CD5 from 1980 to 2000 and correction for exclusion bias tames the slight rise in CD5 after 2005 seen in the right-hand frame of Fig. III.1. What remains is a relatively flat curve that doesn’t tell one anything useful about disruptive science and technology. Sabine Hossenfelder claims that even after the corrections, the green curve in Fig. III.1 still confirms her own bias that science is suffering. But this is pretty weak sauce. Given the legitimate questions that can be raised about whether this disruptiveness index is even a valid metric, corrections for bias basically render the worldwide hand-wringing based on the Park, Leahey, and Funk paper irrelevant to the question of scientific progress.

Prominent scientist-based analysis:

In a 2021 paper in the journal Technological Forecasting & Social Change, Cauwels and Sornette claim to produce evidence that “scientific knowledge…has been in clear decline since the early 1970s for the flow of ideas and since the early 1950s for research productivity.” Their flawed metric defines “the ‘Flow of Ideas’ in a specific year in a certain scientific discipline and geographical region as the number of elite practitioners to be professionally active in that exact cross-section of time, discipline and region. With ‘professionally active’, we mean that: 1) they are alive in that year; 2) they are older than, or equal to 25 years, and, 3) they are younger than 75 years. With ‘elite practitioners’, we mean that they…have been acknowledged in reference works for their contribution to the body of discoveries and inventions. In this we imply that only discoveries and inventions contribute to the body of knowledge. Innovations, on the other hand, do not contribute to, but use the existing body of knowledge.” Note that the exclusion of innovations would eliminate many entries in our Section II list of recent scientific and technical revolutions.

The authors claim that their choice of elite practitioners is not subjective because “we use the databases assembled by Asimov (1989) and Krebs (2008) to extract the discoverers and inventors and not the discoveries and inventions themselves.” They define “research productivity” as their “Flow of Ideas” divided by the total population in a region, as a proxy for the number of researchers in a region in a specific year. Their results for the time-dependence of “Flow of Ideas” and “research productivity” are shown in Fig. III.3.

The curves in Fig. III.3 immediately raise the same sort of red flag as those in Fig. III.1. It is entirely counterintuitive that a timeline for discovery and invention in the life sciences, which have been undergoing tremendous recent progress, should be identical in shape to one for the physical sciences, which had such a paradigm-shifting period in the early 20th century. So these curves most probably again tell us about the flaws in the metric, not about scientific advancement. In particular, the “discoverers and inventors” are sometimes only recognized in retrospect from some time distance, so compilations assembled at one time will, by necessity, disfavor recent developments. And the exclusion of what the authors define as “innovations,” rather than discoveries or inventions, is bound to exclude the majority of “elite practitioners” in a field of science, especially so for developments that are relatively recent for the compilers. The peak in “Flow of Ideas” in 1970 in Fig. III.3 thus mostly reflects oversights of developments that occurred closer to the time of their chosen compilations.

The peak in research productivity near 1950 simply reflects the baby boom that was exploding worldwide population in the post-World War II period, so that the denominator in the authors’ definition of research productivity was growing very rapidly from 1950 to 1970. Not too many of those baby boom babies were already involved in scientific research by 1960 or 1970. A better proxy for the population of scientists would be the adult population.

It is useful to note that Cauwels and Sornette cite in their paper a 2005 study by Huebner, published in the same journal, in which the author attempted to determine the “rate of innovation” over the preceding 500 years by using as a metric “the number of important technological developments per year divided by the world population.” Huebner concluded, nonsensically, that technical innovation peaked in 1873 and has been declining ever since. The rapid rise in world population during the 20th century may have quite a bit to do with that result. The point is that these made-up metrics can give any answer you want, but they all have very little to do with actual scientific and technical progress.

Nobel Prize-based analyses:

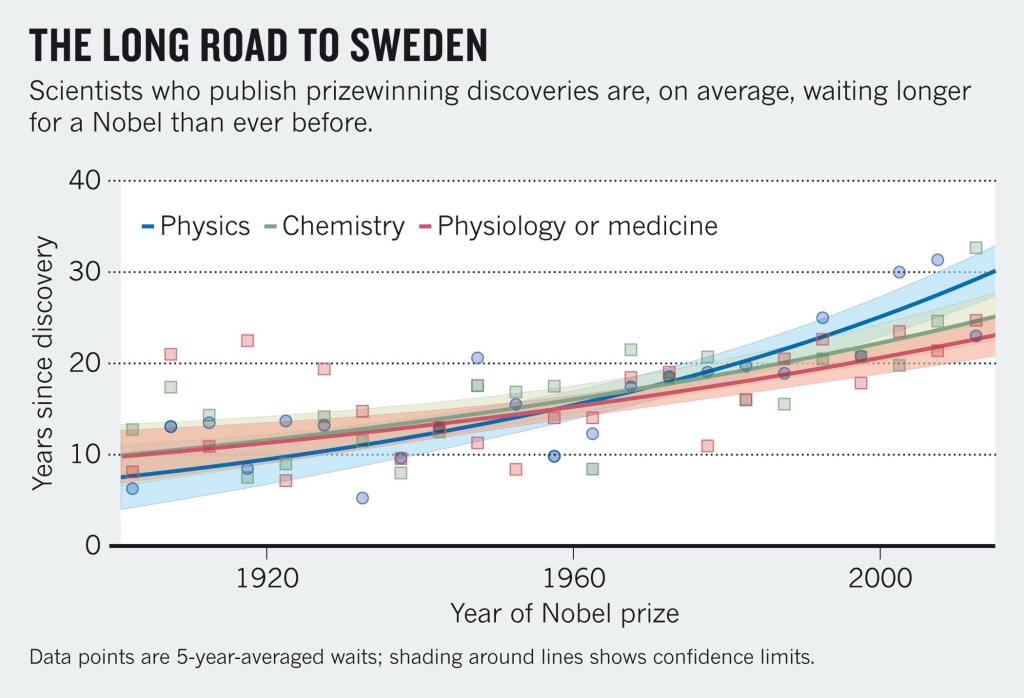

Yet another attempt to define a possibly relevant metric was presented in 2014 by Becattini, et al. They announce their metric in the abstract for their paper: “The time lag between the publication of a Nobel discovery and the conferment of the prize has been rapidly increasing for all disciplines, especially for Physics. Does this mean that fundamental science is running out of groundbreaking discoveries?” Well, to address the question they raise in the abstract, it’s not at all obvious that increasing delay implies fewer groundbreaking discoveries. It is just as possible that, as the forefront of sciences expands in coverage and the number of scientists increases rapidly, there is an increasing backlog in important breakthroughs to be celebrated by a Nobel Prize, so the delay gets longer. But let’s investigate the metric in a bit more detail.

Becattini’s results are combined in a single graph in Fig. III.4. The average delay from discovery to Nobel Prize has been increasing from about 10 years near the inception of the Nobel Prize to more than 20 years in Chemistry and Physiology or Medicine and to 30 years in Physics. Since Physics is the poster child for this increasing delay, we have analyzed in more detail the delays for 21st-century Nobel Prizes in Physics. Since 2000 a total of 46 experimental physicists and 22 theoretical physicists have been awarded the Nobel Prize. For the experimentalists, the average delay from discovery publication to prize is 20.9 years, while for theorists it is 41.5 years. So what is this stark difference in delay times actually telling us?

The recent practice in Nobel Prizes in Physics has been to award theorists under two possible conditions: (1) their predictions have been experimentally verified, or (2) their work underlies recent technical developments. The increasing delay in theory prizes has undoubtedly been influenced by the gradual depletion of “low-hanging fruit” for experiments. Experimental verification of theoretical predictions now often awaits the development of new technology. For example, Peter Higgs and François Englert were awarded the Nobel Prize in 2013 for theories they developed in 1964. But experimental verification of the so-called Higgs mechanism for giving mass to fundamental particles required detection of the Higgs boson and that, in turn, required the development of the world’s highest-energy collider (LHC at CERN), of the world’s most sophisticated and massive particle detectors, and the acquisition of sufficient event statistics to pick out the Higgs signal atop huge background processes. The experimental discovery was made in 2012, so the Nobel Prize was awarded one year after the experimental discovery, but 49 years after the theoretical prediction.

In contrast, the 2017 Nobel Prize for the discovery of gravitational waves was awarded less than two years after the experimental discovery in December, 2015. But if Albert Einstein had still been alive, he might have been awarded for the theoretical prediction of gravitational waves he had made 100 years earlier, since he had never won a Nobel Prize for General Relativity (or even for E=mc2), despite it being one of the most profound advances of the 20th century. And the average theory prize delay, though long, has in fact been pulled downward in our analysis by attaching only a 2-year delay for theoretical cosmologist Kip Thorne, who had in fact been pushing for decades for the development of the Laser Interferometry Gravitational Observatory (LIGO) that was needed to detect the miniscule signals on Earth generated by gravitational waves created millions or billions of light years away.

Similarly, Roy Glauber was awarded a theory prize in 2005 for work performed 42 years earlier, but underpinning the more recent (5-year delay) experimental developments of precision laser spectroscopy that were awarded simultaneously with Glauber. James Peebles was awarded a share of the 2019 Nobel Prize for theoretical cosmology work done about 48 years earlier, along with the experimentalists who had more recently (24-year delay) discovered exoplanets surrounding distant stars. And even the delay for the experimentalists in that case can be explained by waiting for many corroborating exoplanet observations. And the 2024 Nobel Prize was awarded for seminal theoretical developments of machine learning that had been made in the early 1980s, but whose significance grew rapidly as those developments fueled the recent growth of AI.

Furthermore, the average delay for experimental Nobel Prizes in Physics has been raised by several “legacy” Nobel Prizes awarded this century. A 2000 legacy prize awarded the developments of semiconductor heterostructures and integrated circuits some 40 years earlier. A 2009 legacy prize awarded developments of optical fiber technology and CCDs also roughly 40 years earlier. And a 2022 legacy prize awarded experiments that had demonstrated the triumph of quantum mechanics over hidden-variables theories anywhere from 50 to 24 years earlier. These legacy prizes recognize developments whose significance has only increased over time. By the way, that also explains one of the major flaws with the “Flow of Ideas” metric proposed by Cauwels and Sornette: it sometimes takes decades to recognize how significant an earlier development was.

But the Nobel Prizes for immediately recognized major experimental discoveries in physics have usually been awarded in about a decade or less, even in the 21st century: 6 years for the experimental realization of Bose-Einstein condensates (2001 Nobel Prize in Physics); 5 years for precision laser spectroscopy (2005 Nobel Prize in Physics); 6 years for the discovery of graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms in graphite, allowing study of two-dimensional condensed matter systems (2010 Nobel Prize in Physics); 13 years for discovery of the accelerating expansion of the universe (2011 Nobel Prize in Physics); 2 years for detection of gravitational waves (2017 Nobel Prize in Physics).

In summary, the increasing Nobel Prize delays reflect primarily the increasing sophistication of experimental techniques and the increasing development time needed to attain that sophistication. This is certainly true in Physics and we suspect it is also true to a smaller extent in other science fields. To some extent this evolution manifests a truism about the acquisition of knowledge that has been enunciated by Michael Bhaskar in his 2021 book Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking: “The nature of ideas means we must ascend rungs of difficulty and obscurity…All things being equal, future destinations will be harder.” The discoveries being made with these sophisticated techniques are just as groundbreaking as those made earlier in the 20th century, but they take longer to accomplish. That doesn’t mean that “science is running out of groundbreaking discoveries,” but that these discoveries often take more time to develop than they used to. But the cutting edge in sciences is expanding so that more long-gestation breakthroughs are available to award annual Nobel Prizes to groundbreaking developments. Note that many of the milestone developments we included in our seven scientific revolutions in Section II were recognized by Nobel Prizes.

Nobel Prizes were used in a different, even more subjective, way by Collison and Nielsen in their 2018 article entitled Science is Getting Less Bang for its Buck. The authors ran a survey asking leading scientists in their fields to make judgments about the relative significance of Nobel Prize-winning discoveries in the field. The judgments were made in a sort of “March Madness” round-robin tournament in which one discovery was pitted against another. For example, “we might ask a physicist which was a more important contribution to scientific understanding: the discovery of the neutron… or the discovery of the cosmic-microwave-background radiation.” They did this for discoveries made decade by decade from 1901 through 1990. Not too surprisingly, in physics the winning decades were from 1911 to 1930, the decades of the development of General Relativity (1915) and quantum mechanics (1925-28). But the authors conclude from this exercise that “despite vast increases in the time and money spent on research, progress is barely keeping pace with the past.”

The scientists surveyed were clearly not making their judgments on the basis of “bang for the buck,” as suggested by the article’s title. If they had, the 1947 invention of the transistor might come out ahead of General Relativity, which for all its profundity hasn’t generated much bang for the buck, if “bang” is to be understood as return on investment. Our survey of influential scientific and technical developments since 1970 in Section II suggests that scientific progress continues to be quite healthy. But because the number of research scientists and the dollars invested in research have been increasing over time, the question of return on investment is a serious one, to be considered in the next section.

IV. return on investment

What basic trends in scientific research are really driving all of the recent hand-wringing? The best description we have seen was provided by John Drake, a professor of ecology at the University of Georgia, in a 2025 Forbes article entitled Is Science Slowing Down?. As Drake puts it, the “frontier of science has expanded — not narrowed…If we consider scientific knowledge as a volume, then it is bounded by an outer edge where discovery occurs.” One can adapt the same geometric model to approximate the number of research scientists. That number is increasing over time, as represented by the volume contained within an expanding spherical balloon. But the surface area of the balloon, representing the research scientists doing cutting-edge research, is also expanding, just not as rapidly as the volume. As Drake says, the “surface area also expands, and it is along this widening frontier, where the known meets the unknown, that innovation arises.” But as the balloon expands, the ratio of surface area to volume – or equivalently, the fraction of active research scientists involved with cutting-edge research – decreases. The important question for public policy, then, concerns whether the return on investment in research remains healthy.

Collison and Nielsen include in their paper the graph shown in Fig. IV.1. It documents the very rapid increases since 1960 in the number of science and engineering Ph.D.s granted annually in the U.S. (red curve), the number of scientific and engineering publications (purple curve), and the combined NIH (National Institutes of Health) and NSF (National Science Foundation) funding for research in 2017 dollars (blue curve and right-hand axis). The very rapid rises reflect a conscious decision to recruit more young people into science and engineering after the shock of the Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957. And that rise in federal R&D funding and the innovations it generated were major contributors (in one study, to 85%) of the rapid growth in Gross Domestic Product per capita in the U.S. during the second half of the 20th century. A more recent estimate by the group United for Medical Research argued that each dollar the NIH invested in fiscal year 2024 in extramural research funding to U.S. researchers generated $2.56 in new economic activity and new jobs.

On the other hand, Strumsky, Lobo, and Tainter, in a 2010 article entitled Complexity and the Productivity of Innovation, argue that “Our investments in science have been producing diminishing returns for some time…To sustain the scientific enterprise we have employed increasing shares of wealth and personnel.” They argue furthermore that such diminishing returns are inevitable: “As general knowledge is established early in the history of a discipline, that which remains axiomatically becomes more specialized. Specialized questions become more costly and difficult to resolve. Research organization moves from isolated scientists who do all aspects of a project, to teams of scientists, technicians and support staff who require specialized equipment, costly institutions, administrators and accountants. The size of inventing teams grows, a phenomenon paralleled in the increasing size of science authorship teams…fields of scientific research follow a characteristic developmental pattern…from knowledge that is generalized and widely useful to research that is specialized and narrowly useful; from simple to complex and from low to high societal costs.”

It is difficult to take seriously the claim by Strumsky, Lobo, and Tainter that “investments in science have been producing diminishing returns for some time” when the Human Genome Project alone is estimated to have been the single most influential investment in modern science. Federal funding for the project began in 1990 and the project was declared complete in 2003. Since then, “the database has helped enable the identification of a variety of genes that are associated with disease while also revolutionizing the fields of forensics and anthropology. The federal government invested $3.8 billion in the Human Genome Project, which is estimated to have created more than 300,000 jobs and generated an economic output of $796 billion, thus showing a return on investment (ROI) to the U.S. economy of 141 to 1.” (The latter ratio takes into account inflation on the original federal investment.) In addition, the added R&D costs that go into training larger teams of graduate students and post-doctoral scientists should be viewed as a federal investment in providing for future demands for a larger high-tech workforce, so these investments also contribute to national economic productivity.

Furthermore, Strumsky, Lobo, and Tainter paint scientific progress with far too broad a brush. For one thing, the cutting-edge surface of the expanding balloon we have described above is populated very non-uniformly. Consider two of the most important scientific discoveries of the preceding decade. Thousands of collaborators were involved in the enormous experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) that discovered the Higgs boson in 2012 (see Fig. IV.2). At the same time, a half-dozen or so scientists were responsible for discovering the gene-editing capabilities of CRISPR in the same year. Secondly, there is great variability in the “detectability” of economic impact. The CRISPR discovery led immediately to the formation of several biotech startup companies. In contrast, it’s hard to imagine a big economic impact of the Higgs boson. However, preparations for those LHC experiments and the need for far-flung international collaborators to share data and analyses instantly led to the invention of the World Wide Web shortly before the turn of the 21st century. So, the LHC experiments share some hard-to-quantify contribution to the enormous global e-commerce economy.

In addition, economic impact is sometimes long delayed. Einstein’s theory of relativity, developed in 1905, eventually enabled global positioning systems (GPS) and these, in turn, have enabled modern ride-share services such as Uber and Lyft. Billions of dollars have been invested over more than half a century into research aiming to generate net energy from controlled thermonuclear fusion here on Earth. But recent progress in that research has led in recent years to the launch of some 30 startup companies around the world, each hoping to use its preferred technology to become the first to bring commercial fusion power to fruition. The economic return on those billions invested may take a half-century to be realized, but the return has the potential to be huge in the second half of the 21st century.

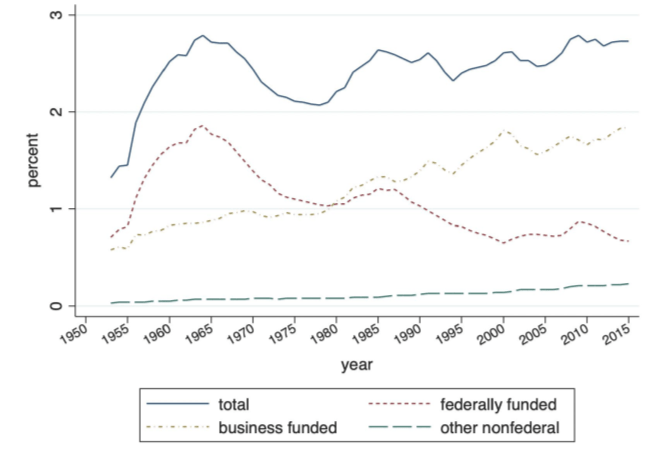

Given these difficulties, it is not surprising that the economic literature does not provide a clear consensus value for return on investment for federally funded R&D. In a recent preprint from the National Bureau of Economic Research, Gullo, Page, Weiner, and Williams survey the recent literature on the subject and come to some broad conclusions. First, they note in the graphs reproduced here as Fig. IV.3 that total funding for R&D in the U.S., in contrast to what one might infer from the rapidly rising curve in Fig. IV.1, has remained roughly constant as a fraction of GDP at roughly 2—3 % since the mid-1960s. However, the federal share of this funding has been steadily decreasing, to a recent value around 0.7%, while private business funding for R&D has grown to about 1.8% of GDP.

The nature of the R&D funding from these two sources is quite different: “around 7% of private R&D and 30% of federal R&D go towards basic research, whereas around 78% of private R&D and 41% of federal R&D go towards experimental development research, with the remainder (15% and 28%, respectively) going towards applied R&D.” The authors argue that economic research supports the conclusion that “basic R&D is less patentable, less easy to appropriate, and generates larger spillovers – and hence, in expectation, generates larger returns in terms of productivity growth.”

To estimate the return, Gullo, et al. rely on two recent papers that use quite different empirical approaches (one macroeconomic and one microeconomic) to arrive at quantitatively similar ROI values, namely, that the historical (from around 1950 to the present) productivity return has been “nearly two dollars on average for each additional dollar of federally funded R&D.” That estimate, however, is quite sensitive to assumptions for the appropriate depreciation rate to be applied to R&D expenditures. There do not appear to be reliable economic studies that indicate that the ROI for federal R&D funding is decreasing over time, as Strumsky, Lobo, and Tainter imply.

One firm conclusion that Gullo, et al. reach is that a considerable amount of evidence indicates that the return on R&D investments is substantially greater than that on investments in physical infrastructure. In contrast, “Many U.S. federal agencies model the economic and budgetary effects of R&D investments as if R&D is the same as any other form of investment, such as physical capital investment.” The consequent underestimate of R&D return in the government, including in the Congressional Budget Office, has quite possibly led to budgeting decisions to underfund science. For example, the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act “aimed to boost US science competitiveness by authorizing major funding increases for three research agencies: the National Science Foundation, Department of Energy Office of Science, and National Institute of Standards and Technology. The law authorized $26.8 billion for fiscal year 2024 and $28.8 billion for fiscal year 2025. But actual appropriations…have fallen drastically short, creating an $8 billion-plus funding gap even as global competitors such as China ramp up R&D investments.”

V. summary

There have been dozens of articles, blogs, videos, and even a book in recent years claiming that science has lost its mojo since about 1970. None of these works have bothered to actually consider and judge the importance of all the major scientific and technical developments over the past half-century. Rather, the authors have been misled by some combination of Thomas Kuhn, flawed metrics, and inappropriate questions.

Kuhn’s influential book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions has implanted in public minds the false impression that the only truly important scientific developments are those few that render everything that has gone before in the field irrelevant, that shift the paradigm in Kuhn’s terminology. As a result, Park, Leahy, and Funk are content to measure, quite erroneously as it turns out, only those scientific publications that are “disruptive,” meaning that nobody afterwards cites anything that happened before the disruptive work. Cauwels and Sornette claim to measure, again erroneously, the “Flow of Ideas” in science by purposely excluding “mere innovators.” None of the authors of works claiming that science is slowing down appear to appreciate that scientific progress is cumulative, that breakthroughs which do not change the paradigm but elucidate critical missing details are essential for dramatically advancing our understanding of nature. And only a few of these authors explicitly recognize that scientific works that transform the way people live are also breakthroughs.

The deeply flawed metrics have not been understood by worldwide media coverage that rushed to ask “What happened to all of science’s big breakthroughs?”. Trying to identify “disruptive” papers by analyzing citation statistics within a database with a fixed start date is fatally flawed if you don’t recognize that papers near that start date will appear more disruptive simply because the works they build upon are not contained in the database. Thus, the title of the paper by Park, Leahey, and Funk, The Decline of Disruptive Science and Technology, is completely unsupported by the analysis they perform. The analysis by Cauwels and Sornette was bound to find a falloff in their “Flow of Ideas” as they approached the date of the surveys they relied on to identify important discoverers and inventors, simply because that somewhat subjective task necessarily becomes more incomplete for more recent work. It sometimes takes decades to understand the importance of earlier scientific work. Thus, the question they raise in their paper’s title, Are ‘Flow of Ideas’ and ‘Research Productivity’ in Secular Decline?, is not usefully illuminated by their analysis. And although Becattini, et al. at least correctly measure the increasing average delay time from scientific publication to awarding of a Nobel Prize, that increasing delay most likely reflects the fact that experimental verification of an earlier theoretical prediction or an earlier surprising experimental result is growing more technically daunting and time-consuming. Despite the increasing delay, worthy Nobel Prizes are awarded every year because the scope of cutting-edge science is expanding.

And what are inappropriate questions to ask of science? Well, two examples are illustrated by Peter Thiel’s expectation that science should by now have made humans immortal and John Horgan’s quest from science, rather than from religion, for The Answer to end all questions. A lot of disappointment is driven by unrealistic expectations.

In this post we have surveyed scientific and technical breakthroughs that have occurred since 1970 and contributed to dramatically advanced understanding of nature and/or dramatically transformed the way people live on Earth. In going beyond Thomas Kuhn’s overly restrictive framework, we have organized these breakthroughs into seven revolutions: in cosmology, genomics, medicine, reproductive science and technology, microelectronics, computation, and energy. Among these seven revolutions we have identified 40 milestone breakthroughs, many of which have already been awarded Nobel Prizes, and a significant number of forefront open questions. We are confident that others could add essential discoveries, inventions, and innovations to our list. But our list already indicates a half-century of admirable scientific productivity. We see no evidence that science is “ending,” “stagnating,” or “slowing down,” even if it has mostly illuminated, but not yet changed, underlying scientific paradigms established especially in the first half of the 20th century.

Some authors have questioned whether the return on investments (ROI) in scientific and technical research and development is as great as it was in the mid-20th century. It is true that there are today more active researchers in science than ever before (even though others claim that the stagnation of science should stop attracting young people into the field). Perhaps a smaller fraction of them are now working at the cutting edge of research. So, doesn’t supporting all those scientists imply less “bang for the buck?” Science and technology have been major drivers of economic advancement. Thus, despite the growth in the number of scientists supported, U.S. federal funding for R&D has actually substantially decreased since the 1960s as a fraction of GDP. And the likely eventual economic payoff for 21st-century research investments in the Human Genome Project, the discovery of CRISPR gene-editing, advances in controlled thermonuclear fusion, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and many other research areas promises to be huge. We have seen no compelling arguments that the ROI for R&D investments is decreasing.

Our diagnosis is that science is quite healthy but a number of commenters on science are suffering from millennial angst.

references:

R. Douthat, Peter Thiel and the Antichrist, New York Times interview, June 26, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/26/opinion/peter-thiel-antichrist-ross-douthat.html

P. Thiel, The End of the Future, National Review, Oct. 3, 2011, https://www.nationalreview.com/2011/10/end-future-peter-thiel/

S. Hossenfelder, Scientific Progress is Slowing Down. But Why?, Science News with Sabine Hossenfelder, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBT9vFrV6yQ

M. Park, E. Leahey, and R.J. Funk, Papers and Patents are Becoming Less Disruptive Over Time, Nature 613, 138 (2023), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-05543-x

The Honest Sorcerer, The End of Science as a Useful Tool, May 20, 2024, https://thehonestsorcerer.medium.com/the-end-of-science-as-a-useful-tool-dbd331995703

P. Collison and M. Nielsen, Science is Getting Less Bang for Its Buck, The Atlantic, Nov. 16, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/11/diminishing-returns-science/575665/

J. Horgan, The End of Science (new edition, Basic Books, 2015), https://www.amazon.com/End-Science-Knowledge-Twilight-Scientific/dp/0465065929

J. Horgan, My Doubts About The End of Science, Nov. 20, 2023, https://johnhorgan.org/cross-check/my-doubts-about-the-end-of-science

T.S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (reissue, University of Chicago Press, 2012), https://www.amazon.com/Structure-Scientific-Revolutions-50th-Anniversary/dp/0226458121/ref=sr_1_1

Blue Origin, New Shepard, https://www.blueorigin.com/new-shepard/fly

DebunkingDenial, What’s New with Renewables?, https://debunkingdenial.com/whats-new-with-renewables/

DebunkingDenial, The Future of Nuclear Power, https://debunkingdenial.com/portfolio/the-future-of-nuclear-power/

V. Masterson, I. Shine, and M. North, 12 New Breakthroughs in the Fight Against Cancer, World Economic Forum, Feb. 27, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/02/cancer-treatment-and-diagnosis-breakthroughs/

M. North, 8 Recent Breakthroughs in the Fight Against Alzheimer’s Disease, World Economic Forum, June 27, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/06/recent-breakthroughs-fight-against-alzheimers-disease/

Wikipedia, Philipp von Jolly, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philipp_von_Jolly

S. Warren, The Hubble Constant, Explained, https://news.uchicago.edu/explainer/hubble-constant-explained

L. Lederman, The God Particle (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1993), https://www.amazon.com/God-Particle-Leon-M-Lederman/dp/0395558492

Wikipedia, Theory of Everything, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theory_of_everything

American Physical Society, May 29, 1919: Eddington Observes Solar Eclipse to Test General Relativity, https://www.aps.org/archives/publications/apsnews/201605/physicshistory.cfm

S. Weinberg, The Revolution That Didn’t Happen, 1998 Colloquium at Department of Physics, Harvard University, https://web.physics.utah.edu/~detar/phys4910/readings/fundamentals/weinberg.html

American Physical Society, May, 1911: Rutherford and the Discovery of the Atomic Nucleus, https://www.aps.org/apsnews/2006/05/rutherford-discovery-atomic-nucleus

American Physical Society, May, 1932: Chadwick Reports the Discovery of the Neutron, https://www.aps.org/apsnews/2007/05/may-1932-chadwick-discovery-neutron

U.S. Department of Energy, DOE Explains…Quarks and Gluons, https://www.energy.gov/science/doe-explainsquarks-and-gluons

Wikipedia, Electroweak Interaction, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electroweak_interaction

Wikipedia, Quantum Chromodynamics, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_chromodynamics

The Hubble Expansion, https://w.astro.berkeley.edu/~mwhite/darkmatter/hubble.html

Wikipedia, Nucleic Acid Double Helix, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nucleic_acid_double_helix

Wikipedia, Plate Tectonics, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plate_tectonics

Wikipedia, Discovery of Nuclear Fission, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discovery_of_nuclear_fission

Wikipedia, History of the Transistor, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_transistor

Our Bodies Ourselves, A Brief History of Birth Control in the U.S., https://ourbodiesourselves.org/health-info/a-brief-history-of-birth-control

C. Goldin, The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Women’s Employment, Education, and Family, Richard T. Ely Lecture, May, 2006, https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/000282806777212350

Wikipedia, Polymerase Chain Reaction, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymerase_chain_reaction

Human Genome Project, https://www.genome.gov/human-genome-project

Nobel Prizes in Physics for 1987, 2000, 2001, 2005, 2006, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2017, 2019, 2021, 2024

Wikipedia, Dark Matter, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_matter

Wikipedia, Dark Energy, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_energy

James Webb Space Telescope, https://science.nasa.gov/mission/webb/

Jamew Webb Space Telescope images, https://science.nasa.gov/mission/webb/multimedia/images/

Vera Rubin Observatory, https://rubinobservatory.org/

Nobel Prizes in Chemistry for 1993, 2019, 2020

DebunkingDenial, The CRISPR Arms Race, https://debunkingdenial.com/portfolio/the-crispr-arms-race/

DebunkingDenial, Humans Now Have the Technology to Bias the Evolution of Species. What Could Possibly Go Wrong?, https://debunkingdenial.com/humans-now-have-the-technology-to-bias-the-evolution-of-species-what-could-possibly-go-wrong/

DebunkingDenial, Envisaging the Invisible Man: Forensic DNA Phenotyping, https://debunkingdenial.com/envisaging-the-invisible-man-forensic-dna-phenotyping/

DebunkingDenial, Reviving Extinct Species, https://debunkingdenial.com/portfolio/reviving-extinct-species/

Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine for 1985, 1987, 2003, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2018, 2022, 2023

B. Liu, A. Saber, and H.J. Haisma, CRISPR/Cas9: a Powerful Tool for Identification of New Targets for Cancer Treatment, Drug Discovery Today 24, 955 (2019), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1359644618305245

P.C. Lauterbur, Image Formation by Induced Local Interactions: Examples Employing Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, Nature 242, 190 (1973), https://www.nature.com/articles/242190a0

Duke Today, Brain Images Just Got 64 Million Times Sharper, Apr. 17, 2023, https://today.duke.edu/2023/04/brain-images-just-got-64-million-times-sharper

Wikipedia, Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Functional_magnetic_resonance_imaging

Mayo Clinic, Robotic Surgery Increases Precision, Shortens Recovery, Dec. 21, 2022, https://www.mayoclinichealthsystem.org/hometown-health/speaking-of-health/robotic-surgery-precision-and-recovery

Cleveland Clinic, Endoscopy, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/25126-endoscopy

National Institutes of Health, Heart, Lung, and Kidney Health, https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/impact-nih-research/improving-health/heart-lung-kidney-health

DrugBank, How Targeted Therapies are Affecting Chronic Disease, Jan. 9, 2025, https://blog.drugbank.com/how-targeted-therapies-are-affecting-chronic-disease/

DebunkingDenial, mRNA Vaccines: Promise and Demonization, https://debunkingdenial.com/mrna-vaccines-promise-and-demonization/

Mayo Clinic, Alzheimer’s Treatments: What’s On the Horizon?, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/in-depth/alzheimers-treatments/art-20047780

L.-K. Huang, Y.-C. Kuan, H.-W. Lin, and C.-J. Hu, Clinical Trials of New Drugs for Alzheimer’s Disease: A 2020—2023 Update, Journal of Biomedical Science 30, 83 (2023), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10544555/

World Economic Forum, 6 Experts Reveal the Technologies Set to Revolutionize Cancer Care, June 3, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/02/cancer-care-future-technology-experts/

Y.L. Vishweshwaraiah and N.V. Dokholyan, mRNA Vaccines for Cancer Immunotherapy, Frontiers in Immunology 13, 1029069 (2022), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9794995/

Human Longevity, Inc., https://www.humanlongevity.com/

L. Guarente, D.A. Sinclair, and G. Kroemer, Human Trials Exploring Anti-Aging Medicines, Cell Metabolism 36, 354 (2024), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1550413123004588

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Preimplantation Genetic Testing, March 2020, https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/03/preimplantation-genetic-testing

Reproductive Partners Medical Group, How Time-Lapse Imaging is Changing Embryo Selection in IVF, https://www.reproductivepartners.com/post/how-time-lapse-imaging-is-changing-embryo-selection-in-ivf

Pharmiweb, Latest Advancements in Reproductive Science, Jan. 20, 2025, https://www.pharmiweb.com/article/latest-advancements-in-reproductive-science

P. Knoepfler, A Close Look at in vitro Gametogenesis or IVG: Making Sperm & Eggs From Stem Cells to Have Kids, The Niche, Feb. 26, 2025, https://ipscell.com/2025/02/a-close-look-at-in-vitro-gametogenesis-or-ivg-making-sperm-eggs-from-stem-cells-to-have-kids/

Wikipedia, Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Induced_pluripotent_stem_cell

S. Rees and R. Harding, Brain Development During Fetal Life: Influences of the Intrauterine Environment, Neuroscience Letters 361, 111 (2004), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304394004001351?via%3Dihub

I. Savic, A. Garcia-Falgueras, and D.F. Swaab, Sexual Differentiation of the Human Brain in Relation to Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation, Progress in Brain Research 186, 41 (2010), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21094885/

Wikiwand, Artificial Womb, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Artificial_womb

Colossal Biosciences, https://colossal.com/

DebunkingDenial, Ramifications of the Accelerating Worldwide Baby Bust, https://debunkingdenial.com/ramifications-of-the-accelerating-worldwide-baby-bust-part-i-data-and-causes/

DebunkingDenial, Still Relevant After All These Years, Part II, https://debunkingdenial.com/still-relevant-after-all-these-years-part-ii/

Wikipedia, Moore’s Law, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moore%27s_law

Wikipedia, MEMS, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MEMS

Adobe Acrobat Team, Fast-Forward – Comparing a 1980s Supercomputer to the Modern Smartphone, Nov. 8, 2022, https://blog.adobe.com/en/publish/2022/11/08/fast-forward-comparing-1980s-supercomputer-to-modern-smartphone

B. Hossain, The Future of Integrated Circuits: Trends and Innovations, https://electroniccomponent.com/future-of-integrated-circuits-trends-and-innovations/

NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory LSST Camera Focal Plane, https://www6.slac.stanford.edu/media/lsstcam-focalplane-lowresjpg

Association for Computing Machinery, Inventor of World Wide Web Receives ACM A.M. Turing Award, 2016, https://awards.acm.org/about/2016-turing

DebunkingDenial, The Cyberhogs: Part II, Artificial Intelligence, https://debunkingdenial.com/the-cyberhogs-part-ii-artificial-intelligence/

Wikipedia, Quantum Computing, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_computing

B. Cottier, et al., How Much Does it Cost to Train Frontier AI Models?, Jan. 13, 2025, https://epoch.ai/blog/how-much-does-it-cost-to-train-frontier-ai-models

Google Cloud, What Is Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)?, https://cloud.google.com/discover/what-is-artificial-general-intelligence

DebunkingDenial, Can You Create an Evil AI? Let’s Ask Grok, https://debunkingdenial.com/can-you-create-an-evil-ai-lets-ask-grok/

C. Bolgar, A Million Qubits Within Reach as Microsoft Redefines Quantum Computing, SciTechDaily, March 2, 2025, https://scitechdaily.com/a-million-qubits-within-reach-as-microsoft-redefines-quantum-computing/

DebunkingDenial, Ten False Narratives of Climate Change Deniers, https://debunkingdenial.com/ten-false-narratives-of-climate-change-deniers-part-i/

DebunkingDenial, Climate Tipping Points: Coming Soon to a Planet Near You, https://debunkingdenial.com/climate-tipping-points-coming-soon-to-a-planet-near-you/

World Nuclear Association, Molten Salt Reactors, https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/molten-salt-reactors

International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, https://www.iter.org/

D. Chandler, MIT-Designed Project Achieves Major Advance Toward Fusion Energy, MIT News, Sept. 8, 2021, https://news.mit.edu/2021/MIT-CFS-major-advance-toward-fusion-energy-0908

Advanced Energy Technologies, Global Electricity Review 2024: A Record 30% of Renewables in Global Electricity Generation in 2023, https://aenert.com/news-events/energy-news-monitoring/n/global-electricity-review-2024-a-record-30-of-renewables-in-global-electricity-generation-in-2023/

R. Semenov, Science and Technology Are Becoming Less Disruptive, Minnesota Carlson School, Jan. 19, 2023, https://carlsonschool.umn.edu/news/science-and-technology-are-becoming-less-disruptive

W.J. Broad, What Happened to All of Science’s Big Breakthroughs?, New York Times, Jan. 17, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/17/science/science-breakthroughs-disruption.html

D. Thompson, The Consolidation-Disruption Index is Alarming, The Atlantic, Jan. 11, 2023, https://www.theatlantic.com/newsletters/archive/2023/01/academia-research-scientific-papers-progress/672694/

R. Hart, Where Are All the Scientific Breakthroughs? Forget AI, Nuclear Fusion, and mRNA Vaccines, Advances in Science and Tech Have Slowed, Major Study Says, Forbes, Jan. 4, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/roberthart/2023/01/04/where-are-all-the-scientific-breakthroughs-forget-ai-nuclear-fusion-and-mrna-vaccines-advances-in-science-and-tech-have-slowed-major-study-says/

Science Is Losing Its Ability to Disrupt, Financial Times, Jan. 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/c8bfd3da-bf9d-4f9b-ab98-e9677f109e6d

J.G. Arranz, Publicar o Perecer: El Conocimiento Científico se Expande, Pero la Innovación Disruptiva se Estanca, El Pais, Jan. 4, 2023, https://elpais.com/ciencia/2023-01-04/publicar-o-perecer-el-conocimiento-cientifico-se-expande-pero-la-innovacion-disruptiva-se-estanca.html

D. Larousserie, Dans la Recherche, des Découvertes de Moins en Moins Révolutionnaires, Le Monde, Jan. 11, 2023, https://www.lemonde.fr/sciences/article/2023/01/11/dans-la-recherche-des-decouvertes-de-moins-en-moins-revolutionnaires_6157375_1650684.html

J.T. Macher, C. Rutzer, and R. Weder, Is There a Secular Decline in Disruptive Patents? Correcting for Measurement Bias, Research Policy 53, 104992 (2024), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048733324000416?via%3Dihub

P. Cauwels and D. Sornette, Are ‘Flow of Ideas’ and ‘Research Productivity’ in Secular Decline?, Technological Forecasting and Social Change 174, 121267 (2022), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040162521007010

Asimov’s Chronology of Science and Discovery, https://www.asimovreviews.net/Books/Book431.html

R.E. Krebs, Encyclopedia of Scientific Principles, Laws, and Theories (Greenwood Press, 2008), https://www.amazon.com/Encyclopedia-Scientific-Principles-Laws-Theories/dp/0313340064

J. Huebner, A Possible Declining Trend for Worldwide Innovation, Technological Forecasting and Social Change 72, 980 (2005), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0040162505000235

F. Becattini, et al., The Nobel Prize Delay, Nature 508, 186 (2014), https://arxiv.org/abs/1405.7136

Wikipedia, LIGO, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LIGO

M. Bhaskar, Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking (MIT Press, 2022), https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262545105/human-frontiers/

J. Drake, Is Science Slowing Down?, Forbes, May 26, 2025, https://www.forbes.com/sites/johndrake/2025/05/26/is-science-slowing-down/

D. Souvaine, Research and Innovation: Ensuring America’s Economic and Strategic Leadership, U.S. Senate testimony, Oct. 22, 2019, https://nsf-gov-resources.nsf.gov/pubs/2020/nsbct102219/nsbct102219.pdf

United for Medical Research, NIH’s Role in Sustaining the U.S. Economy, FY2024, https://www.unitedformedicalresearch.org/annual-economic-report/

D. Strumsky, J. Lobo, and J.A. Tainter, Complexity and the Productivity of Innovation, Systems Research and Behavioral Science 27, 496 (2010), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/sres.1057

Science and Technology Action Committee, The Incredible, Incomparable ROI of R&D, https://sciencetechaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/The-Incredible-Incomparable-ROI-of-RD_5.15-1.pdf

1927 5th Solvay Conference on Quantum Mechanics, https://marinamaral.com/portfolio/solvay-conference/

ATLAS Collaboration, https://atlas.cern/Discover/Collaboration

T. Gullo, B. Page, D. Weiner, and H.L. Williams, Estimating the Economic and Budgetary Effects of Research Investments, National Bureau of Economic Research, Jan. 2025, https://www.nber.org/papers/w33402

J. Pethokoukis, Federal R&D Funding is Even More Valuable Than Washington Thinks, American Enterprise Institute, Jan. 28, 2025, https://www.aei.org/economics/federal-rd-funding-is-even-more-valuable-than-washington-thinks/

Wikipedia, CHIPS and Science Act, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CHIPS_and_Science_Act