September 26, 2024

V. The National academies 2016 report on gmo foods

The National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) is one of the premier scientific organizations in the world. It has 2,000 members and 400 foreign associates. The incoming class of members is elected by the current membership of NASEM. NASEM regularly conducts studies and issues reports on controversial issues in science, engineering and medicine. For the past 40 years, NASEM has issued reports on agriculture and technology. In 2016, NASEM created a panel that conducted a study of the health and safety aspects of genetically engineered crops. The panel had 20 members, including four members of the National Academy of Science. The results of that panel were published in a report titled Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects. The charge to the committee that produced the 600-page report was to examine the “food safety, environmental, social, economic, and regulatory aspects of transgenic crops.” First, the committee established a definition of genetic engineering, as “The introduction of or change of DNA, RNA, or proteins manipulated by humans to effect a change in an organism’s genotype or epigenome.” The NASEM panel made a distinction between genetic engineering and biotechnology. The committee included in the ‘biotechnology’ definition methods such as mutagenesis that is induced by chemical or nuclear methods, also “some in vitro culture techniques that enable wide crossing of plants.” The front page of the NASEM report is shown in Fig. V.1.

One critical area of study was a comparison of crop yields from transgenic plants and from plants that were raised using conventional methods. The study also looked for environmental impacts of transgenic crops. The NASEM report addressed a new generation of animal feeding studies. These were studies where lab animals such as rats, pigs or mice were given food that replaced those raised by traditional means with transgenic food of the same crop. The groups of animals were then tested to see if any abnormalities were found in the group that had received the transgenic crops. The panel also looked for epidemiological effects in humans from countries where GMO foods were common and compared those results with health outcomes from countries where GMOs were banned.

A: Conclusions of the NASEM Panel

It is worthwhile to first list the main findings from the NASEM panel. In the following sub-sections we will review and comment on various aspects of the study and detailed findings from the committee regarding various issues.

- First, the panel concluded that there was no evidence yet that genetically engineered or GE crops had any adverse effects on human health. This has been a consistent theme of all such scientific studies of GE crops, that there has never been any convincing demonstration of adverse health effects on humans. The panel “examined epidemiological data on incidence of cancers and other human-health problems over time and found no substantiated evidence that foods from GE crops were less safe than foods from non-GE crops.”

- Next, the panel found no adverse health effects on livestock that were fed GE foods. This was accomplished by comparing the health of livestock before and after being exposed to GE foods.

- Some GE crops have been provided with genes that make the plant resistant to certain insects. Such crops have generally received genes from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis or Bt. The panel found that when fields were planted with crops that had the Bt trait, crop losses due to insect predation decreased; hence, the yield would often increase when transgenic insect-resistant crops were planted. Also, such fields had greater insect biodiversity than fields that had been treated with chemical insecticides. However, “in locations where resistance-management strategies were not followed, damaging levels of resistance evolved in some target insects.”

- The NASEM panel emphasized that with bacterial insecticides, if those products were toxic the toxicity almost always showed up immediately at very low concentrations; thus, the panel maintained that Bt-treated crops would generally be regarded as safe, if toxic results were not discovered in initial rounds of testing.

- The panel found that farmers who used GE soybeans, maize and cotton “generally had favorable economic outcomes;” however, “outcomes have been heterogeneous depending on pest abundance, farming practices, and agricultural infrastructure.”

- The panel also studied crops that had been genetically modified to acquire herbicide resistance or HR. The most common HR crops are genetically engineered so that they are resistant to the herbicide glyphosate (the active ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup). A highly controversial question is whether ‘Roundup Ready’ plants have higher yields than traditional crops. The panel found that HR crops sprayed with glyphosate “often had small increases in yield in comparison with non-HR counterparts.” However, when planting HR crops “led to a heavy reliance on glyphosate, some weeds evolved resistance and present a major agronomic problem.”

- The NASEM report studied the introduction of Dow Chemical’s herbicide Enlist Duo, which contained both glyphosate and 2,4-D. The EPA had previously tested glyphosate, so in the Dow product they tested both 2,4-D by itself, and the Enlist Duo product that contained both chemicals. The panel concluded, “When herbicides are used on a new GE crop, EPA assesses the interaction of the mixture as compared to the individual herbicidal compounds.”

- The report concludes that “The nation-wide data on maize, cotton or soybean in the United States do not show a significant signature of genetic-engineering on the rate of yield increase.”

B: What is “Substantial Equivalence”?

The NASEM study emphasized the similarities between traditional methods of plant breeding, and genetic engineering of plants. There are significant differences between the U.S. and Europe in their treatment of genetically modified foods. In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) assumes that GMO foods are “substantially equivalent” to crops grown through the traditional methods of plant breeding. The concept of substantial equivalence first arose in 1999, when the FDA argued that a class of new medical devices did not differ in any significant way from their predecessors and hence did not need any new regulations. The FDA’s starting assumption is that GMO foods are “generally regarded as safe,” or GRAS. Internationally, risk assessment guidelines have been “adopted by the Codex Alimentarius Commission, established by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization and the World Health Organization.” These state that if all significant differences between a GMO and its traditional form can be identified, and if all these differences are shown to be safe for human health, then the GMO is determined to be “substantially equivalent” to its conventional counterpart.

There are two issues with this method for assessing risk. First, although “substantial equivalence” between GMOs and traditional plants is the crucial test for the safety of GMOs, there is no precise definition for substantial equivalence. In fact, advocates for GMOs and skeptics often differ on the degree to which GMOs and traditional plants are equivalent. A second issue is how nations determine “substantial equivalence.” In the U.S., the starting assumption is that transgenic crops and traditional crops will have very similar effects on human health. Thus, GMOs are assumed to be “generally regarded as safe,” or GRAS. The FDA leaves testing of GMO products up to the food manufacturers who created the product. Unless proven otherwise, the FDA accepts that the food manufacturers have tested the products and found them to be safe. The FDA maintains a “voluntary consultation” process, whereby they invite the food manufacturers to share data with the FDA on the toxicology, nutritional value or allergenic properties of the GMOs.

The situation regarding GMOs is very different in the European Union. In the EU, the designation of GRAS has to be demonstrated before approval is given for the GMO food to be adopted. The manufacturers must provide data on the composition of the GE crop relative to the traditional crop. If this is not sufficient to prove the safety of the transgenic crop, then the EU recommends animal studies to check for possible health effects. The EU recommends both short-term 90-day animal studies, and longer-term studies if necessary to rule out chronic health issues.

The European Union has been criticized for over-regulating commerce, and for adopting rules that stifle entrepreneurs. However, we feel that the FDA should not assume that genetically modified organisms are safe unless health problems arise. Nor should the FDA rely on chemical companies to carry out their own research, and voluntarily share it with the FDA. If our history with such companies led us to trust their actions, then we might argue that our regulatory agencies should take the word of such companies without independently checking it. Unfortunately, our history is filled with examples where large corporations have deliberately misled the public and government regulators, with disastrous consequences. Chemical companies often fail to publicize internal research that shows potential negative health effects from their products. Here, we cite just a few instances of issues where large manufacturers, and particularly chemical companies, touted the safety of products that turned out to be highly toxic.

- During the Vietnam War, the U.S. dropped millions of pounds of Agent Orange, a defoliant and herbicide, on Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. The purpose was to destroy crops and defoliate forests in those areas. Figure V.2 shows a Fairchild C-123 Provider aircraft spraying defoliant in South Vietnam in 1962. Agent Orange was a compound that consisted of two herbicides, 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D. The 2,4,5-T was contaminated with dioxin, in particular the extremely toxic compound called TCDD. Nine American companies produced the herbicide, including Dow Chemical and Monsanto. Agent Orange devastated the ecology of those countries; various observers, including Swedish Prime Minister Olaf Palme, described the American actions as ecocide. In addition, the dioxin compound TCDD exposed millions of citizens of Southeast Asia, and American soldiers who handled these products, to extremely dangerous carcinogenic chemicals. Furthermore, over successive generations, dioxin works its way up the food chain and becomes concentrated in the bodies of those who consume the crops. The manufacturers of Agent Orange, particularly Monsanto, insisted that “reliable scientific evidence indicates that Agent Orange is not the cause of serious long-term health effects.” However, when lawsuits by Vietnam veterans made it to court, the manufacturers agreed to pay $180 million in compensation in return for veterans dropping all charges against them. Subsequent studies have shown without doubt that the dioxin in Agent Orange has caused a wide range of cancers and other diseases, and that it continues to produce cancers in the children of those affected.

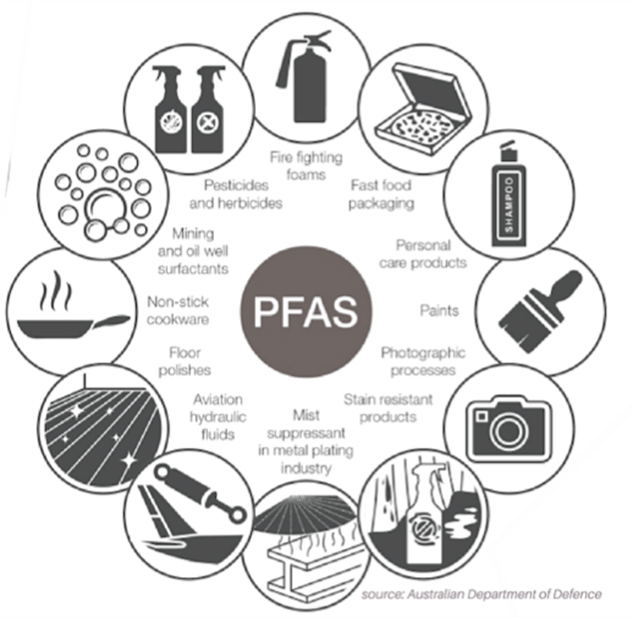

- Chemicals of a class called poly-fluoroalkyl substances or PFAS have a wide variety of applications, because the chemicals are so stable. Figure V.3 shows some of the vast number of industrial uses for PFAS chemicals. In carrying out research on potential applications of various PFAS chemicals, scientists at DuPont and 3M discovered the toxicity of these chemicals. However, they kept these results to themselves and did not follow up on initial studies that indicated these products might be toxic. The sordid history of PFAS chemicals, now called ‘Forever chemicals’ because of their persistence in the system and the environment, and the fact that they now show up nearly everywhere, is summarized in our blog post on Toxic Product Defenders. For DuPont, one type of PFAS chemical called PFOA played an essential role in their Teflon products; for 3M, PFOS chemicals were important in their Scotchgard stain-repellent fabrics. When health problems with PFAS were finally made public by researchers, 3M rapidly stopped producing those products. However, DuPont hired a “toxic product defenders” company led by Michael Dourson to recommend a “safe level” of PFOA in drinking water. Dourson claimed that a safe level was 150 parts/billion in drinking water; the state of West Virginia, where a large DuPont plant used PFAS chemicals and pumped them into the water, immediately adopted Dourson’s number (which was conveniently larger than the levels in drinking water around the DuPont plant). The current ‘safe’ level adopted by the EPA is 4 parts per trillion; thus Dourson’s “safe limit” was too high by a factor of almost 40,000. DuPont hired even more law firms to contest what they knew to be true – that PFAS chemicals were extremely hazardous to the health of humans, animals and the ecosystem. It is now known that PFAS chemicals have serious negative effects on immune system function, a fact that 3M scientists discovered in 1978 but then suppressed. After years of litigation (some of which is still ongoing) DuPont and 3M have settled lawsuits for well over a billion dollars in damages resulting from their failures to reveal their early indications of toxicity.

- We have covered the essential role of the pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma in creating the opioid epidemic in our blog post on this topic. Purdue Pharma was owned and run by the Sackler family. The company spent millions of dollars promoting the idea that citizens around the globe were in chronic pain and needed large doses of opioids. At that time, because of the high risk that they would cause addiction, significant doses of opioids could only be prescribed to terminally ill patients. The company asserted that their drug OxyContin was safe for the general public because the large doses of morphine in that product were released slowly, over time. They claimed, with no real proof, that addiction from OxyContin almost never occurred. Purdue Pharma eventually received FDA approval for their product and marketed it relentlessly. OxyContin was, indeed, a powerful pain reliever; it was also highly addictive. Patients quickly realized that if OxyContin was crushed and diluted with water, all its pain-relieving qualities would be instantly released – indeed, the packaging label stated that this would occur. Millions of doses of OxyContin were sold, many to people who had become dependent upon it, or to people abusing the drug to produce a ‘rush.’ Purdue Pharma continued to insist that the product was safe, even though they knew otherwise. The family made billions off the product. Roughly ten years ago, Sackler family members began withdrawing billions of dollars from Purdue Pharma; when the company declared bankruptcy in 2019, it had less than a billion dollars in assets. Hundreds of thousands of Americans became addicted to opioids after being exposed to OxyContin. This epidemic of addiction and death could have been avoided had Purdue Pharma been honest about its product. Figure V.10 shows a protest against the Sackler family at the headquarters of Purdue Pharma in Stamford, Connecticut. The protesters claimed that Purdue’s aggressive marketing of OxyContin and its lies about the safety of that product jump-started the nation’s opioid crisis.

In addition to the cases above, we have previously discussed in detail Monsanto’s long efforts to cover up indications that their product Roundup is probably carcinogenic to humans, as it has indeed been designated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. Based on the behavior by these large American corporations, we cannot argue with any certainty that these companies would honestly report potential health or contaminating issues with their products. To the contrary, these companies went to great lengths to avoid responsibility for the toxicity of their products. They hid research results that suggested adverse effects of their products; they used teams of lawyers to deny the toxicity of their products; they hired ‘toxic product defenders’ to release studies intimating that their products were safe. When people who had been injured by these products sued, the companies eventually paid them off; however, they often insisted that the records of the case be closed, so that future victims of those products were unable to see the evidence that they were hazardous.

The appropriate role of federal agencies in preventing companies from deceiving the public with toxic products is a difficult issue. We have mentioned only a few of many examples where our regulatory agencies have been hoodwinked by large chemical corporations. Unfortunately, there has long been a two-way pathway in which regulators often transition into or out of the same chemical companies they are allegedly regulating. In cases such as the PFAS chemicals, which are now found nearly everywhere in soil and ground water, the long-term damage may be catastrophically large and the costs of mitigation prohibitive. All of this suggests that agencies such as the FDA should be substantially more proactive in requiring that companies prove the safety of their products. In this area, the European Union takes proactive steps that require companies to demonstrate that their products are not health hazards.

However, there is pervasive criticism in the U.S. contending that EU regulations are too burdensome, that they discourage innovation and that because of these regulations, European products take too long to reach the market. There is a trade-off between the costs of additional testing, and the benefits to society of reduction in risk obtained from such testing. Although we do not want to see innovation stifled, the examples we have given show that the health and safety of Americans has been seriously compromised in the past by allowing companies to hide the toxicity of their products. Critics of GMO foods tend to focus on unintended consequences that might arise from the insertion of new genes into products; critics maintain that this is particularly likely when the new genes are those from species that are quite different from those of the traditional crop. The NASEM report tends to emphasize the fact that unintended consequences that show up in secondary metabolites can arise in both transgenic crops and in traditional methods of plant breeding.

C: Composition Analyses

Some of the testing methods scrutinized by the NASEM panel involved “whole food” studies and composition analyses. In many studies, individual chemicals in GE plants are investigated, rather than chemical mixtures or whole foods. In this way, researchers don’t have to consider the diverse mixtures of chemicals but can concentrate on a single chemical. However, the NASEM panel did review some whole-foods studies. In particular, they focused on a 2012 study carried out by French molecular biologist Gilles-Eric Séralini and initially published in the journal Food and Chemical Toxicology. Séralini was the president of the board of the Committee of Research and Independent Information on Genetic Engineering (CRIIGEN). This is an organization opposed to GM food; in fact, Séralini became a co-founder of the group in 1999 because he was convinced that studies of GM foods failed to show the dangers of these products.

In his 2012 paper, Séralini announced that his team had carried out a two-year study of 100 male and 100 female Sprague-Dawley rats that were fed maize that had varying amounts of GE corn, and also were fed water that had varying amounts of Roundup; control groups had non-GE maize and pure water. The Séralini team reported that rats fed GE corn and Roundup developed tumors at a higher rate than the controls. At the press conference announcing the publication, Séralini showed a number of gruesome photos of diseased rats that had been given GE maize and Roundup. However, the study immediately came under attack from scientific groups. As expected, industry-supported groups attacked the findings; however, the results were also lambasted by independent groups of scientists. A major point of criticism was that the conclusions were unjustified by the small sample of rats (ten rats in each separate group). Also, Sprague-Dawley rats are naturally prone to tumors and have a very high probability of developing a tumor during their two-year lifetime.

Marion Nestle, the Paulette Goddard professor in the Dept. of Nutrition, Food Studies and Public Health at New York University, and a leading advocate for food safety, gave a critique that echoed remarks from various scientific groups. “I can’t figure it out yet … [the paper is] weirdly complicated and unclear on key issues; what the controls were fed, relative rates of tumors, why no dose relationship, what the mechanisms might be. I can’t think of a biological reason why GMO corn should do this … So even though I strongly support labeling, I’m skeptical of this study.” The Séralini study had the strange result that rats on a diet of 11% GE maize had more tumors than the group fed a 33% mixture; thus, as mentioned by Prof. Nestle there was apparently no dose-response relationship. Criticism of the Séralini study from institutes in France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, New Zealand and Brazil was so intense that in 2013, Food and Chemical Toxicology retracted the article after the authors refused to withdraw it. In 2012, scientists at the University of Nottingham School of Biosciences issued a review of 12 studies of rats fed GE soybeans lasting up to two years, and 12 studies involving as many as 5 generations; they found “no apparent adverse effect in rats.”

The NASEM panel discounted the Séralini study in its 2016 report. One of the things it focused on was the fact that traditional crops can also produce secondary metabolites with some degree of toxicity; they emphasized that transgenic crops and traditional crops can both produce such metabolites. This marks a divide between the “traditional scientific community” and GMO food critics. The scientific community argues that both transgenic and traditional crops have similar risks, and that there is no evidence that GMO foods have demonstrated increased risks to human health. In fact, in some cases the secondary metabolites confer health benefits on those who consume them. For example, compounds in legumes such as soybeans may help prevent certain cancers and cardiovascular disease, and some antioxidants may provide anti-cancer benefits. Thus, the 2016 NASEM study concludes that “Conventional breeding and genetic engineering can cause unintended changes in the presence and concentrations of secondary metabolites.” On the other hand, GMO critics claim that the insertion of foreign genes into traditional crops represents an additional degree of risk, and that GMO advocates have not sufficiently investigated the possibility of long-term health risks.

In 2015, Krimsky reviewed a number of studies of health effects from transgenic products. He found eight reviews of such health effects, some of which concluded that there were negative health effects from GMOs and some that found no such effects, and twenty-six individual studies that reported adverse effects from GMO products. The NASEM panel had concluded that “The committee could not find persuasive evidence of adverse health effects directly attributable to the consumption of GE foods.” However, the NASEM panel only referred to four of the eight reviews found by Krimsky, and only four of the twenty-six studies that reported adverse effects. This is puzzling as it leaves open to speculation regarding why the NASEM panel did not cite these papers.

Composition analyses involve isolating various nutrients and chemicals in a plant and comparing their prevalence in traditional plants with transgenic versions of the same plant. For example, the NASEM review mentions a study by Dow AgroSciences comparing 62 different compounds in conventional soybeans with their prevalence in Roundup Ready soybeans. The Dow study found statistically significant differences in 16 of the 62 compounds that they assessed. However, the differences that they found fell within the range of variation in those compounds found in different varieties of naturally-occurring soybeans. Therefore, the Dow group concluded that the variations they found between natural and transgenic soybeans were statistically significant, but not ‘biologically meaningful.’ The NASEM study endorsed this point of view.

D: ‘Omics’ Analyses:

The NASEM study reviewed the use of new molecular biology technologies to more accurately assess and compare the concentrations of messenger RNAs, proteins and small molecules in a plant or food. The NASEM study mentioned three types of these ‘omics’ analyses.

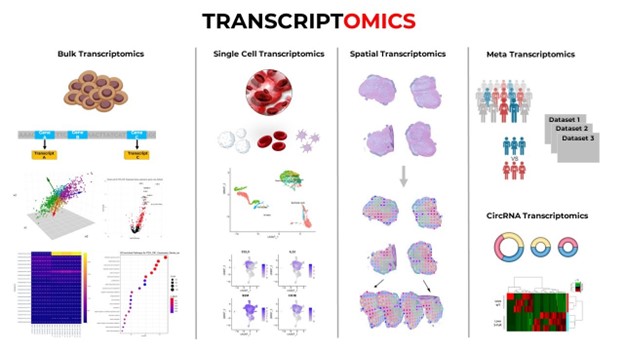

- Transcriptomics: Transcriptomics involves the techniques used to study an organism’s transcriptome, which involves the sum of all of that organism’s RNA transcripts. There are two major processes that allow information to be collected rapidly regarding an organism’s transcriptome. The first is DNA microarray, and the second is a rapid-sequencing process called RNA-seq. Since 2010, RNA-seq has been the dominant method used to collect this information. Data obtained from the transcriptome can be used to study processes such as “cellular differentiation, carcinogenesis, transcription regulation and biomarker discovery.” Figure V.5 shows various different techniques that are used in this field. From left: bulk transcriptomics, that examines “the collective gene expression within a population of cells or tissues.” With this technique, “one can obtain insights into the average gene expression patterns across a sample.” Next is single-cell transcriptomics; this approach allows scientists to scrutinize gene expression profiles at the level of an individual cell. Spatial transcriptomics provides information on the “spatial organization of cells within tissues or organisms.” And Meta transcriptomics studies all of the transcripts within a microbial community; this method allows one to “study the functional roles of different microbial species.”

- Proteomics: Proteomics involves the study of the proteome, “the entire set of proteins produced or modified by an organism or system.” The most powerful technique used with proteomics is mass spectrometry. The field of proteomics was kick-started by results from the Human Genome Project. Figure V.6 gives a schematic representation of three different types of proteomics studies on peptides. The top frame, or ‘bottom-up’ proteomics, selects and analyzes molecules from a group of small peptides; the middle frame, or ‘middle-down’ proteomics, separates and analyzes peptides from a group of large peptides; the bottom frame, or ‘top-down’ proteomics, separates and analyzes a proteoform from a group of intact proteins.

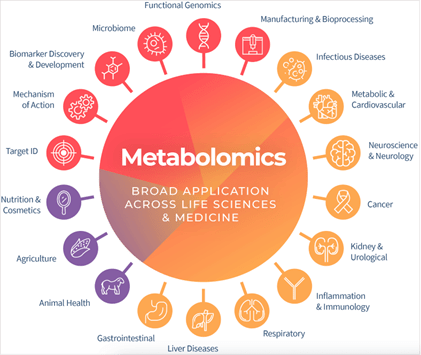

- Metabolomics: Metabolomics involves the study of chemical processes that involve metabolites, which are small molecules within cells, biofluids, tissues or organisms. The collection of metabolites within a biological system is known as the metabolome. Figure V.7 is a schematic picture showing the many different fields of biology and human health that are impacted by metabolite studies.

The NASEM panel emphasized that these new quantitative methods, particularly when all of them are combined, have the potential to discover minute changes between traditional and transgenic plants, and to determine the significance of such changes. As one example, the panel noted that a study comparing ‘Roundup Ready’ GE soybeans with traditional beans found that three free amino acids, and an amino-acid precursor, and flavonoid-derived secondary metabolites occurred in higher concentrations in the GE soybean than in the traditional crop, while the metabolite 4-hydroxyl-1-threonine was present in the traditional bean but absent in the GE variety. The panel emphasized the detailed information that could be extracted using these new techniques. They concluded that “in most cases examined, differences between GE and non-GE plants obtained from -omics analyses were small relative to the naturally occurring variation found in conventional crops; however, these -omics analyses appear to be the most promising avenue to discover unexpected changes in composition with GE plants.”

E: Human Health Studies of GE Plants:

The panel searched for links between GE crops and the occurrence of diseases and chronic conditions. The committee was particularly interested in whether the prevalence of certain diseases was linked to the introduction of GE foods. They admitted that the most useful data would be long-term epidemiological studies of disease trends. If such studies appeared to show a link between the disease and GE foods, then additional specific tests should be carried out both with human data and with animal research.

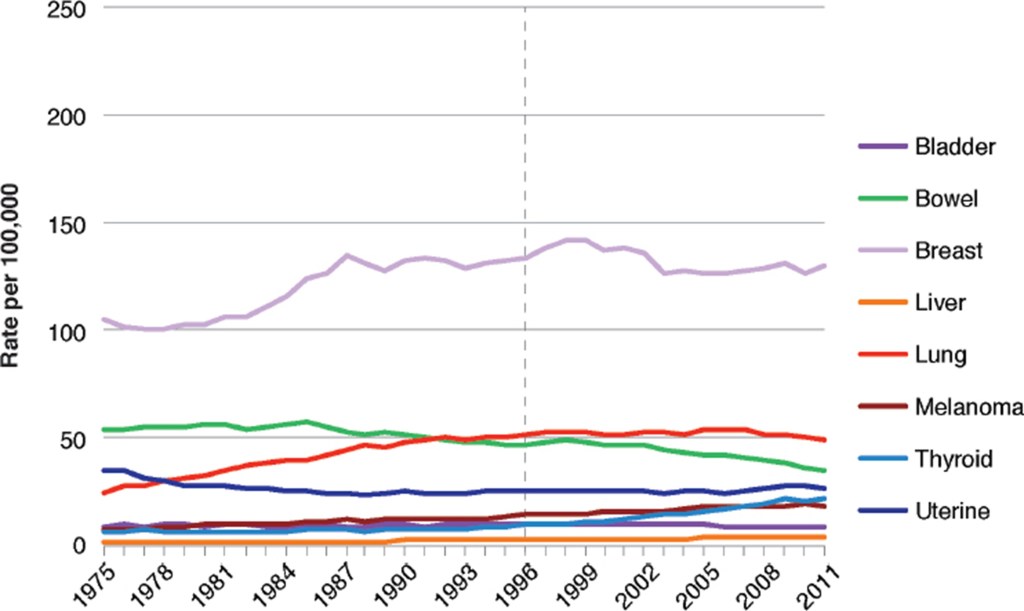

The first disease studied was cancer. The committee relied on data on cancer incidence rather than cancer mortality, since mortality could be affected by improvements in treatment. The first study was of the incidence of cancer in American women during the period 1975 – 2011. Figure V.8 shows the incidence of eight cancers (bladder, bowel, breast, liver, lung, melanoma, thyroid and uterine) over this period. There is a vertical dashed line at 1996, the first year that GE corn and soybeans were commercially available. There are no discernible sharp changes in the rate of such cancers from 1996. The data in Fig. V.8 do not support a hypothesis that various cancers in American women are a result of the introduction of GE foods. However, they do not prove that there is no relationship between cancer and GE foods. For one thing, it is far from clear how the consumption rate of GE crops varied in this very large sample. For another, there could be a delayed effect that would not show up for a significant amount of time. Also, there could be an increase in cancer due to GE foods that was obscured by a decrease in the incidence of that cancer from some other source.

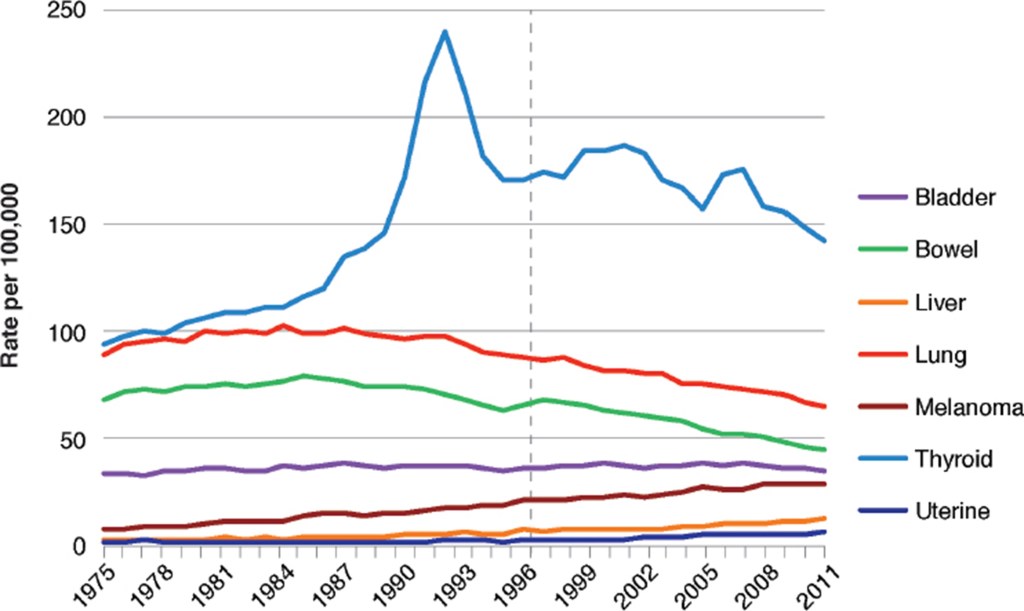

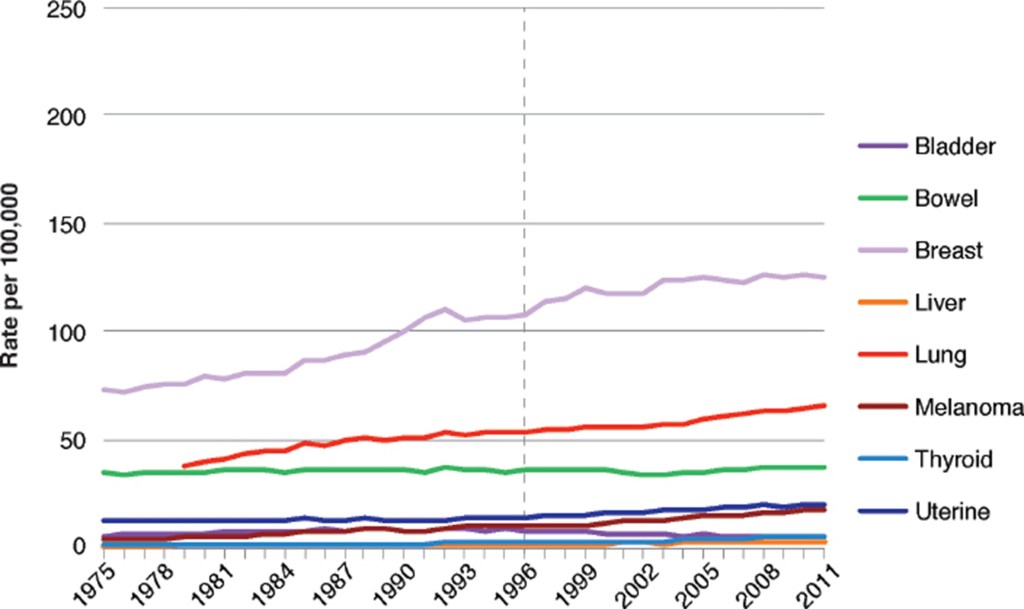

Figure V.9 shows the incidence of the same cancers among American men (except for uterine cancer). Again, there is no discernible change in the rate of incidence of any cancer beginning in 1996. Figure V.10 shows the incidence of these same cancers in women in the United Kingdom during the same period of time. It is interesting to compare Figs. V.8 and V.10; since GE foods were not readily available in the U.K., any increases in cancer incidence in that country were not due to the ingestion of GE foods. The NASEM report concluded: “The incidence of a variety of cancer types in the United States has changed over time, but the changes do not appear to be associated with the switch to consumption of GE foods. Furthermore, patterns of change in cancer incidence in the United States are generally similar to those in the United Kingdom and Europe, where diets contain much lower amounts of food derived from GE crops.”

Of particular concern is the effect of glyphosate on humans. There is a contested history of the toxicity of glyphosate (the active chemical in Monsanto’s Roundup). GE soybeans and maize are transgenic products that have inserted genes into these plants so that they develop tolerance for Roundup. When Roundup is sprayed on ‘Roundup Ready’ fields, the crop plants are resistant to that chemical whereas (at least initially, before they evolve to develop resistance to Roundup) Roundup kills varieties of weeds in those fields.

In 1985, the EPA classified glyphosate as Group C, meaning possibly carcinogenic to humans, because of tumor formation found in mice exposed to that chemical. However, in 1991 the EPA re-classified glyphosate as Group E (evidence of non-carcinogenicity in humans) after new mouse data was submitted; the Group E classification was later reaffirmed based on two rodent carcinogenicity studies. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World Health Organization (WHO) classified glyphosate in Group 2A, probably carcinogenic to humans. The IARC argued that while there was “limited evidence in humans for the carcinogenicity of glyphosate,” there was “sufficient evidence in experimental animals for the carcinogenicity.” Following the IARC report, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that glyphosate was unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk. The Canadian health agency concluded that exposure to glyphosate, even by farm hands who worked directly with that chemical, did not pose a health concern as long as it was used as directed.

The NASEM report concluded: “There is significant disagreement among expert committees on the potential harm that could be caused by the use of glyphosate on GE crops and in other applications. In determining the risk from glyphosate and formulations that include glyphosate, analyses must take into account both marginal exposure and potential harm.”

In addition to the investigations we have listed thus far, the NASEM panel also studied the following potential sources of adverse health effects from GE foods: kidney disease; obesity and type II diabetes; gastrointestinal tract diseases; celiac disease; food allergies; autism spectrum disorder; gastrointestinal tract microbiota; horizontal gene transfer to gut microorganisms or animal somatic cells; and transfer of transgenic material across the gut barrier into animal organs. In every case, the panel was unable to find any significant link between GE foods and the health effect in question. However, their studies depend heavily on comparisons of disease incidence in the U.S. and the E.U. While there is certainly a large difference between those two populations in consumption of GMO foods, there are many additional differences in diet, behavior, and environment that provide confounding variables for any serious epidemiological analysis. Meaningful epidemiological studies, involving control groups with very similar characteristics other than GMO food consumption, have not been carried out yet and it is nearly impossible to do so in the absence of clear labeling of the GMO foods in the U.S.

The NASEM panel drew the following conclusions regarding their study of possible adverse effects on human health from foods derived from GE crops: “On the basis of detailed examination of comparisons of currently commercialized GE and non-GE foods in compositional analysis, acute and chronic animal-toxicity tests, long-term data on health of livestock fed GE foods, and human epidemiological data, the committee found no differences that implicate a higher risk to human health from GE foods than from their non-GE counterparts.”

F: Potential Conflict of Interest Among Members of the NASEM GMO Panel

NASEM is sensitive to potential conflicts of interest among scientists appointed to their studies. Government agencies require financial conflict of interest (fCOI) disclosures for members on advisory panels. In 1997, amendments were made to the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) regarding committees formed by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine. The new rules specified that federal agencies could not use recommendations from NASEM committees unless two conditions were met. Those conditions were:

- No member of a NASEM committee can have a conflict of interest relative to the subject under study unless NASEM determines that a conflict is unavoidable. If such a determination is made, it must be disclosed promptly and publicly.

- Membership on a NASEM committee must be fairly balanced.

Responding to the new FACA requirements, NASEM developed its own conflict-of-interest guidelines.

In their 2016 report on GE crops, NASEM stated that, among the 20 scientist members of the panel, there were no conflicts of interest. In Feb. 2017, Krimsky and Schwab published an article studying the makeup of the NASEM panel. They found that 6 of the 20 panel members “had financial interests in genetically engineered crops, including patents and corporate research grants.” It would appear that the 6 members of the committee on GE crops had clear conflicts of interest; even if NASEM believed that their presence on the committee was essential, they should have released a statement acknowledging the conflicts and explaining why those members were essential for the study. However, NASEM released a statement that categorically rejected the claims of Krimsky and Schwab. The statement read: “The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine have a stringent, well-defined, and transparent conflict-of-interest policy with which all members of this study committee complied. It is unfair and disingenuous for the authors of the PLOS article to apply their own perception of conflict of interest in place of our tested and trusted conflict-of-interest policies.”

The NASEM statement appeared to be a resounding rejection of the arguments by Krimsky and Schwab, and a full-throated defense of their conflict-of-interest policy. However, just three months later the President of NASEM announced that the academies were revising their conflict-of-interest policies. The byline of that article stated that “The proposed changes follow revelations in recent years that committee members preparing reports for the Academies did not disclose industry relationships.” So much for the “tested and trusted” conflict-of-interest policies of NASEM. To be fair, the NASEM report’s conclusions do not differ from those of other scientific reviews of GE crops, but the possibility of undisclosed conflicts of interest among the panel members casts a bit of a shadow over the report’s impact.

VI. the saga of golden rice

Golden rice was the first GE crop designed specifically to improve human health. Golden rice is a genetically engineered rice, that contains beta-carotene which has been added to the inner volume of the rice by transgenic methods. The structure of rice, prior to milling, consists of an outer coat containing the husk and bran; an inner volume, the endosperm; and a central embryo. Although the outer coat of the rice contains some beta-carotene, that is all removed in the milling process that produces white rice. Golden rice is the result of a research project by Ingo Potrykus of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and Peter Beyer of the University of Freiburg; they are shown in Fig. VI.1. The first details of the procedure developed by Potrykus and Beyer were published in 2000.

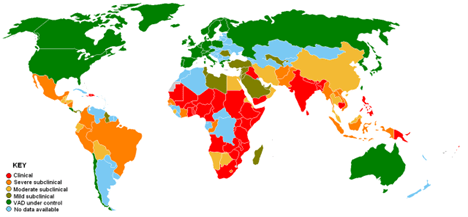

Potrykus and Beyer were motivated to undertake this project because white rice is a main feature of the diet of millions of people in Asia, Africa and the South Pacific. It is estimated that 3 billion people depend on rice as their staple crop. Because white rice is deficient in vitamin A, a number of those children suffer from vitamin A deficiency or VAD, a condition that can lead to blindness and death. Vitamin A “has been shown to play an essential role in vision, immune response, epithelial cell growth, bone growth, reproduction and embryonic development.” Figure VI.2 shows the incidence of VAD in countries around the globe. Red denotes those countries where VAD is most common, while green denotes areas where VAD is under control; blue shows those countries with no data on VAD. It is estimated that VAD leads to about a million deaths per year, and that roughly 230 million children suffer from VAD, which can make them prone to infections. So Potrykus and Beyer were convinced that Golden Rice might be a game-changer, preventing up to a million deaths per year, provided that they could introduce a sufficiently large amount of beta-carotene into the rice, and that the beta-carotene would be converted by the human body into vitamin A.

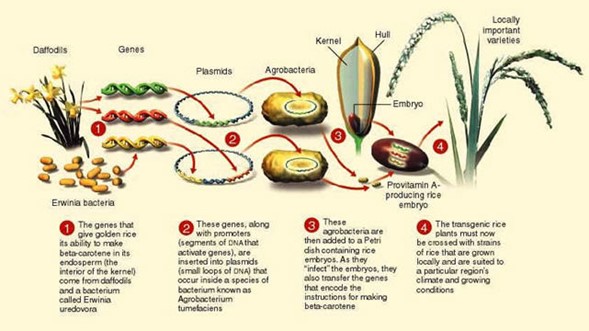

The team led by Potrykus and Beyer introduced genes for expressing beta-carotene using a recombinant DNA sequence depicted schematically in Fig. VI.3. They first took genes from a daffodil (Beyer had worked with daffodils in his research) and a gene from a bacterium Erwinia uredovora found in soil. Those genes were then inserted into loops of DNA (called plasmids) extracted from the bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens. After the recombined plasmids are reinjected, the agrobacteria are then inserted into rice grain embryos, where they transfer the genes that encode instructions for making beta-carotene. The good news was that the researchers could demonstrate that after consuming this transgenic rice, humans would convert the beta-carotene into vitamin A. The bad news was that the initial strain of golden rice produced 1.6 micrograms (µ-grams) of protovitamin A per gram of rice. With this amount, a child would have to consume 3 kilograms of rice daily in order to reach the minimum daily requirement of vitamin A. However, the research team stated that this first step was merely a proof of principle, and that subsequent versions of Golden Rice would be able to produce rice containing a suitable amount of vitamin A precursors. The label “Golden Rice” was appropriate; Fig. VI.4 shows a bowl of ordinary white rice in the foreground, together with the genetically modified Golden Rice that contains beta-carotene that is converted into vitamin A in the human body.

In 2012, the results of a study of Golden Rice were published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. The study was organized by researchers from Tufts University and involved “seventy-two healthy children between six and eight years old from Huan, China.” The children were divided into three equal-size groups. One group was fed 60 grams of Golden Rice a day for 21 days; a second group was fed white rice supplemented with vitamin-A capsules; and a third control group only received white rice. After 21 days, the blood concentration of vitamin A was measured; it was found that the Golden Rice group had received the same amount of that vitamin as the group that received white rice with supplementary vitamin A.

Initially, the study was considered a landmark accomplishment. Unfortunately, in 2015 the study was retracted. The consent form provided to the children by Tufts University mentioned that some of the group would receive Golden Rice. However, the form neglected to specify that this product had been genetically modified. Therefore, it was determined that the parents of the children who participated in the trial had not been provided with enough information for them to give “informed consent.” This was just one of the unfortunate setbacks associated with efforts to bring Golden Rice to market.

Throughout this process, it was clear that Potrykus and Beyer saw their goal as providing millions of children on several continents with sufficient vitamin A to prevent the many debilitating injuries and deaths associated with VAD. The two scientists founded the Golden Rice Humanitarian Board, with a goal of providing this cultivar to the public at a cost that did not exceed the current prices for rice. They worked out an agreement with Syngenta to allow that company to develop the next generation of Golden Rice, and this agreement included a promise that farmers who earned less than $10,000 per year would obtain the technology for free. Syngenta replaced the original daffodil promoter gene with a maize gene; this increased the yield of protovitamin A by a factor of twenty-three. They claimed that a child who consumed 60 grams (about one third of a cup) of Golden Rice per day would receive 60% of the Chinese recommended daily allowance of vitamin A; this would be sufficient to prevent vitamin A deficiency.

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office announced that the Golden Rice project was one of the 2015 winners of the Patents for Humanity Awards. In October 2019, the Golden Rice humanitarian project was listed as one of the top-10 Biotech Projects of the past 50 years by the US-based Project Management Institute. Golden Rice has been recognized as safe in the U.S., Australia, Canada and New Zealand. In 2021, the Philippines became the first country to approve commercial cultivation of Golden Rice. This was a landmark decision, as per capita rice consumption in the Philippines in 2018 was 115 kg/year. However, the Philippines rapidly became a battleground between scientists, who insisted that Golden Rice was completely safe, and activists who argued that Golden Rice was unsafe. The opposition was led by Greenpeace. Wilhelmina Pelegrina, head of Greenpeace Philippines, stated that “Farmers, who brought this case with us … currently grow different varieties of rice, including high-value seeds they have worked with for generations and have control over. They’re rightly concerned that if their organic or heirloom varieties get mixed up with patented, genetically engineered rice, that could sabotage their certifications, reducing their market appeal and ultimately threatening their livelihoods.” Pelegrina argued that people could obtain vitamin A in other ways, such as taking supplements or eating other crops that were high in vitamin A.

A concern of Greenpeace and their farmer allies is that the transgenic rice would cross-pollinate with other natural strains of rice, including organic varieties. This would “sabotage” those existing varieties. However, field tests of golden rice showed that the transgenic rice could co-exist with other rice varieties, provided that the fields were separated by a distance of a few meters. Furthermore, cross-pollination would only occur naturally if both varieties were flowering at the same time. Critics of Golden Rice also claimed that in India, transgenic rice plants of the Swarna variety of rice flowered later, were half the height of normal plants, and were also half as fertile. Yield was reported to be only one-third of the normal crop. However, this occurred with an early version (GR2R) of transgenic rice. When a more promising GR2E version was used, tests in the Philippines and Bangladesh showed that the obtained grain quality and yield equaled that of normal rice. Furthermore, the transgenic GR2E rice resistance to pests and disease also equaled that for normal strains of rice. The Golden Rice GR2E strain was then crossbred with local rice varieties in Bangladesh and the Philippines. It was demonstrated that the resulting rice strains passed on the genes that expressed beta-carotene from generation to generation.

The consensus of scientists was that Golden Rice was completely safe. Ingo Potrykus stated that “Golden Rice was the first transgenic crop to be created that benefited people not companies or farmers, yet its use has been blocked from the start.” He stated that “GMO opposition has to be held responsible for the foreseeable unnecessary death and blindness of millions of poor every year.” In 2016, a group of over 150 Nobel Laureates in science issued a letter that criticized the Greenpeace opposition to Golden Rice, which began long before the specific battles in the Philippines. The letter stated “Scientific and regulatory agencies around the world have repeatedly and consistently found crops and foods improved through biotechnology to be as safe as, if not safer than those derived from any other means of production. There has never been a single confirmed case of a negative health outcome for humans or animals from their consumption.”

In April 2023, after years of lawsuits from Greenpeace and farmers, the Philippines court of appeals ordered the country’s agriculture department to stop commercial production of Golden Rice, in response to a petition filed by a group of farmers and scientists. In April 2024, the court revoked the approval of Golden Rice and issued a cease and desist order for the growth of that product in the Philippines. This was hailed as a “monumental victory” by Greenpeace. Among other things, Greenpeace had argued that Golden Rice would likely become the single dominant strain of rice, and decrease the diversity of rice strains, making it less resilient to climate change. Also, they stated that Golden Rice was a ‘stalking horse,’ a ploy to introduce more and more genetically modified foods.

However, scientists had a very different reaction to the decision. Professor Martin Qaim, a member of the Golden Rice Humanitarian Board, stated “The court’s decision is a catastrophe. It goes completely against the science, which has found no evidence of any risk associated with Golden Rice, and will result in thousands and thousands of children dying.” The Golden Rice Project stated that “Adoption of biofortified crops like Golden Rice can show their greatest potential as a safe, culturally simple and economically sustainable amelioration due to the simple facts that smallholders can grow and multiply their own biofortified crops and that such crops can vastly reduce the need for supplementation campaigns requiring recurring assembly of a costly labour and travel infrastructure to reach all those in need in the most remote areas.” The court decision is being challenged by the Philippine government and may well be overturned in the future. At the moment, it represents a significant setback for Golden Rice.

There are ongoing efforts to produce other biofortified crops. All use similar methods – gene editing methods such as CRISPR/Cas9 are used to insert genes that will improve the nutrient composition of staple crops. Some of the genetically engineered crops that are under development, and the enhanced nutrients they contain, are cassava (vitamin A), potato (vitamin C), tomato (vitamin C), broccoli (vitamin C), wheat (zinc), maize (beta-carotene) and rice (folate). However, given the fights over Golden Rice, it should be assumed that all of these biofortified foods will be challenged by the same groups using the same arguments. We did note in section II, however, that tomatoes gene-edited to enhance gamma-aminobutyric acid, believed helpful in reducing anxiety, stress, and high blood pressure in humans, are already available for sale in Japan.

It should be noted that the situation with Golden Rice is very different from that for Roundup Ready crops. In the case of Roundup Ready crops, genes are inserted into seeds for corn or soybeans that make those crops resistant to the chemical glyphosate (the weed-killer in Roundup). Every year, farmers are required to purchase their seeds from Bayer (previously from Monsanto), and when they spray their fields with Roundup, the crops are not killed by the chemical, but the weeds are. This gives Bayer/Monsanto an enormous amount of control over actions by the farmers; the seeds are licensed annually from Bayer, but Bayer retains ownership. However, over time weeds will develop resistance to Roundup, which means that the farmers will have to use more or different pesticides on their fields. On the other hand, the purpose of Golden Rice is to increase the nutritional value of a staple crop by using biotechnology. Members of the Golden Rice Humanitarian Board are quite correct in claiming that their actions and motives are very different from the proprietary techniques used by companies such as Monsanto. And their intention is that “smallholders can grow and multiply their own biofortified crops.” It would seem that the critics of Golden Rice are motivated in part by an aversion to any genetically engineered plants, regardless of the human health benefits offered by Golden Rice.

VII. outlook

The main questions consumers have regarding GMO foods are: is the food safe for consumption? What does it do to improve my quality of life? The current status of assessments of safety can be best summarized by saying that there is, as yet, no compelling evidence for any adverse health effects of GMO foods on humans. We say this despite the fact that there are clear chemical and genetic differences between GMO and non-GMO foods, and despite a few animal studies that have suggested possible negative effects, though without convincing statistics or control of the experiments.

However, we don’t view the current status as clear enough to alter public perceptions that GMO foods are unsafe. Consumer attitudes in the U.S. are not helped by the Food and Drug Administration’s policy of trusting GE seed manufacturers to do and report their own testing. This policy seems to ignore the considerable history we have exposed in other posts on this site of large corporations and industries going to extraordinary lengths to hide their own internal evidence of dangers to human health and the environment from their profitable products. We prefer the E.U. approach to approval of new GMO foods, but even that approach can be improved by requiring the type of ‘-omics’ analyses we discussed in Section V. Clear results on health impacts will require long-term, large-sample epidemiological comparisons of health outcomes for people who do regularly consume GMO foods with control groups of people of comparable age distribution, environmental exposure, behavior (e.g., with respect to smoking), and diet except for not consuming GMO foods at all. In the U.S., such comparisons can begin to be possible only once there are laws requiring clear labeling of all GMO foods, so that consumers know what they are choosing to eat. The current National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard does not meet that need, since it allows for confusing labeling that is not likely to yield clear consumer choices.

The only advantage offered to consumers from the majority of GMO foods marketed to date is the promise of lower prices facilitated by increased agricultural productivity. Many crops have been genetically engineered to introduce tolerance to herbicides or resistance to insects and to viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. Those changes do prevent significant crop losses in the short term. However, insects, viruses, bacteria, and fungi evolve quickly to overcome the resistance of plants on which they thrive and weeds evolve quickly to resist the herbicides to which GE crops have been made tolerant. There is thus likely to be an ongoing battle between GE seed manufacturers and the adaptation of the pests they seek to disarm, just to maintain the early gains in agricultural yields, and that battle will bring little additional advantage to consumers.

Yet another issue is the question of whether transgenic seeds will mix with, and contaminate, traditional seed varieties. The Union of Concerned Scientists investigated this question in 2004 and issued a report on the issue. At that time they found that “seeds thought to be free of GE material are in fact pervasively contaminated. Based on these findings, we are concerned that the seed supply is inadequately protected from contamination by pharma/industrial crops.” The UCS recommended that “the federal government immediately take the following steps to address seed supply contamination and prevent seed contamination by pharma/industrial crops.” To be fair, the level of contamination in 2004 was very small, but the report emphasized the fact that the level of contamination would almost certainly increase, and that contamination from transgenic seeds threatened the purity of traditional seeds used in organic farming.

The smaller number of attempts to date to use genetic engineering to improve the quality or nutritional value of foods have not yet had sustained success. The saga we have reviewed with regard to Golden Rice, engineered specifically to ameliorate vitamin A deficiency prevalent in many populations worldwide but never brought to market, is a sad tale in which organized opponents of GMO foods have likely thrown the baby out with the bath water. Many patents have now been granted to apply CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to improve the taste, shelf life, or nutritional value of specific GMO foods, and some of the resulting foods are now approved for market (see Fig. II.4). These hold the promise of improving consumers’ quality of life more directly than the earlier GMO foods, though concerns about safety will remain pending more complete analysis in some of these cases.

The greatest long-term threat to agriculture is not from weeds, insects, or diseases, but rather from climate change. As we have described in a previous post, human-caused global warming will alter precipitation patterns globally throughout the rest of this century. Some regions will experience frequent flooding while others experience extended droughts, damaging agricultural productivity in both cases. Throughout the history of human civilization, extended droughts have led to the collapse of agriculture and of human societies, most recently to the 21st century Syrian civil war and subsequent mass migrations. Thus, the greatest long-term benefit of genetic engineering for agriculture will come when the seed manufacturers begin to address the impacts of climate change. When gene editing can be applied to make crops more tolerant of excessively low or high water content in the soil, GMO foods will establish important long-term value. We look forward to the use of human engineering to ameliorate the agricultural problems caused by the cumulative human burning of fossil fuels.

references:

S. Krimsky, GMOs Decoded: A Skeptic’s View of Genetically Modified Foods (MIT Press, 2019), https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262039192/gmos-decoded/

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects (National Academies Press, 2016), https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/23395/genetically-engineered-crops-experiences-and-prospects

DebunkingDenial, Reviving Extinct Species, https://debunkingdenial.com/reviving-extinct-species-part-i-background-and-saving-endangered-species/

DebunkingDenial, Humans Now Have the Technology to Bias the Evolution of Species; What Could Possibly Go Wrong?, https://debunkingdenial.com/humans-now-have-the-technology-to-bias-the-evolution-of-species-what-could-possibly-go-wrong/

S. Nyamweya, Why GMO Foods Should Be Banned, https://discover.hubpages.com/food/Why-GMO-Foods-should-be-banned-in-US

National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard, U.S. Law passed 2016, https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ216/PLAW-114publ216.pdf

Wikipedia, Roundup Ready, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roundup_Ready

Wikipedia, Glyphosate, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glyphosate

DebunkingDenial, Case Studies in Toxic Product Defense, https://debunkingdenial.com/part-ii-case-studies-in-toxic-product-defense/

Center for Food Safety, Glyphosate, https://www.centerforfoodsafety.org/issues/6459/pesticides/glyphosate

D. Normile, Gene-Edited Foods are Safe, Japanese Panel Concludes, Science, Mar. 19, 2019, https://www.science.org/content/article/gene-edited-foods-are-safe-japanese-panel-concludes

Genetic Literacy Project, Where are GMO Crops and Animals Approved and Banned?, https://geneticliteracyproject.org/gmo-faq/where-are-gmo-crops-and-animals-approved-and-banned/

Wikipedia, Genetically Modified Food in the European Union, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genetically_modified_food_in_the_European_Union

Anjali Singh, What is Embryo Rescue?, https://plantcelltechnology.com/blogs/blog/blog-what-is-embryo-rescue

Wikipedia, Mutagenesis, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mutagenesis

Wikipedia, The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Effect_of_Gamma_Rays_on_Man-in-the-Moon_Marigolds

DebunkingDenial, The CRISPR Arms Race, https://debunkingdenial.com/the-crispr-arms-race-part-i/

Wikipedia, Recombinant DNA, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recombinant_DNA

R.F. Kratz, Recombinant DNA Technology, https://www.dummies.com/article/academics-the-arts/science/biology/recombinant-dna-technology-269996/

Wikipedia, Endonuclease, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endonuclease

Wikipedia, Golden Rice, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_rice

B. Liu, A. Saber, and H.J. Haisma, CRISPR/Cas9: A Powerful Tool for Identification of New Targets for Cancer Treatment, Drug Discovery Today 24, 955 (2019), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1359644618305245

Drug Law Institute, Winter, 2021, The Future of Food? CRISPR-Edited Agriculture, https://www.fdli.org/2021/11/the-future-of-food-crispr-edited-agriculture/

P. Pontoniere, Foods Genetically Edited Using CRISPR Technology are Beginning to Hit Store Shelves. How are They Different from GMOs?, https://proto.life/2023/07/crispr-crops-are-here/

J.M.T. Hunt, C.A. Samson, A. du Rand, and H.M. Sheppard, Unintended CRISPR/Cas9 Editing Outcomes: A Review of the Detection and Prevalence of Structural Variants Generated by Gene-Editing in Human Cells, Human Genetics 142, 705 (2023), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10182114/

A. Ahmad, A. Jamil, and N. Munawar, GMOs or Non-GMOs? The CRISPR Conundrum, Frontiers in Plant Science 14, 1232938 (2023), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10591184/

Global Gene-Editing Regulation Tracker, United States: Crops/Food, https://crispr-gene-editing-regs-tracker.geneticliteracyproject.org/united-states-crops-food/

B. Kennedy and C.L. Thigpen, Many Publics Around World Doubt Safety of Genetically Modified Foods, Pew Research Center, Nov. 11, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/11/11/many-publics-around-world-doubt-safety-of-genetically-modified-foods/

International Agency for Research on Cancer, Some Organophosphate Insecticides and Herbicides, https://publications.iarc.fr/549

U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Organic Food Retail Sales by Category, 2001-2021, https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=55444

S. Marette, A-C. Disdier, and J.C. Beghin, A Comparison of EU and US Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Gene-Edited Food: Evidence from Apples, Appetite 159, 105064 (2021), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S019566632031686X

C. Funk and B. Kennedy, Americans’ Views About and Consumption of Organic Foods, Pew Research Center, Dec. 1, 2016, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2016/12/01/americans-views-about-and-consumption-of-organic-foods/

Greenpeace, GMOs, https://www.greenpeace.org/eu-unit/tag/gmos/

J. Achenbach, 107 Nobel Laureates Sign Letter Blasting Greenpeace Over GMOs, Washington Post, June 30, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2016/06/29/more-than-100-nobel-laureates-take-on-greenpeace-over-gmo-stance/

Institute for Science in Society, “GM-Free Organic Agriculture to Feed the World”, https://www.i-sis.org.uk/GMFreeOrganicAgriculture.php

Wikipedia, Gene Gun, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gene_gun

P. Cohen, Roundup Maker to Pay $10 Billion to Settle Cancer Suits, New York Times, June 24, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/business/roundup-settlement-lawsuits.html

Roundup Ready Crops: Key Players, https://web.mit.edu/demoscience/Monsanto/players.html

Department of Toxic Substances Control, Acute Oral Toxicity, https://dtsc.ca.gov/acute-oral-toxicity/

Union of Concerned Scientists, The Rise of Superweeds – and What to Do About It, https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/2019-09/rise-of-superweeds.pdf

N.K. van Alfen (editor), Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems, 2nd Edition (Academic Press, 2014), https://www.amazon.com/Encyclopedia-Agriculture-Food-Systems-Alfen/dp/0444525122

X.D. Wei, et al., Field Released Transgenic Papaya Affects Microbial Communities and Enzyme Activities in Soil, Plant Soil 285, 347 (2006), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11104-006-9020-8

Wikipedia, Silent Spring, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silent_Spring

DebunkingDenial, Scientific Tipping Points: The Banning of DDT, https://debunkingdenial.com/scientific-tipping-points-the-banning-of-ddt-part-i/

Wikipedia, StarLink Corn Recall, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/StarLink_corn_recall

D.L. Uchtmann, StarLink – A Case Study of Agricultural Biotechnology Regulation, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267403455_StarLink_-_A_case_study_of_agricultural_biotechnology_regulation

N. Rubio-Infante and L. Moreno-Fierros, An Overview of the Safety and Biological Effects of Bacillus Thuringiensis Cry Toxins in Mammals, Journal of Applied Toxicology 36, 630 (2016), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26537666/

H.I. Miller, Substantial Equivalence: Its Uses and Abuses, Nature Biotechnology 17, 1042 (1999), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10545866/

J. Withrow, Don’t Stifle U.S. Tech Innovation with Europe’s Rules, R Street op-ed, Oct. 9, 2022, https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/withrow-dont-stifle-u-s-tech-innovation-with-europes-rules-opinion/

Wikipedia, Agent Orange, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agent_Orange

DebunkingDenial, Purdue Pharma and America’s Opioid Epidemic, https://debunkingdenial.com/purdue-pharma-and-americas-opioid-epidemic-part-i/

G.-E. Séralini, et al., Long Term Toxicity of a Roundup Herbicide and a Roundup-Tolerant Genetically Modified Maize (RETRACTED), Food and Chemical Toxicology 50, 4221 (2012), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278691512005637?via%3Dihub

A.W. Hayes, Editor in Chief of Food and Chemical Toxicology Answers Questions on Retraction, Food and Chemical Toxicology 65, 394 (2014), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278691514000076?via%3Dihub

Wikipedia, Séralini Affair, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C3%A9ralini_affair

J. Entine, Does the Séralini Corn Study Fiasco Mark a Turning Point in the Debate Over GM Food?, Forbes, Apr. 13, 2014, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jonentine/2012/09/30/does-the-seralini-corn-study-fiasco-mark-a-turning-point-in-the-debate-over-gm-food/

S. Krimsky, An Illusory Consensus Behind GMO Health Assessment, Science, Technology, & Human Values 40, 883 (2015), https://www.jstor.org/stable/43671260

Wikipedia, Transcriptome, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transcriptome

S. Ray, Unveiling the Diversity of Transcriptomic Studies: Types, Case Studies, and Learning Resources, LinkedIn, Oct. 16, 2023, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/unveiling-diversity-transcriptomic-studies-types-case-sonalika-ray-fksff/

Wikipedia, Proteomics, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proteomics

S. Tamang, Proteomics: Types, Methods, Steps, Applications, Microbe Notes, Aug. 3, 2023, https://microbenotes.com/proteomics/

Wikipedia, Metabolomics, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metabolomics

Metabolon, Chapter 4 – The Importance of Metabolomics Insights, https://www.metabolon.com/why-metabolomics/your-guide-chapter-4-importance-metabolomics-insights/

R. Garcia-Villalba, et al., Comparative Metabolomic Study of Transgenic versus Conventional Soybean Using Capillary Electrophoresis—Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry, Journal of Chromatography A 1195, 164 (2008), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18508066/

K.Z. Guyton, et al., Carcinogenicity of Tetrachlorvinphos, Parathion, Malathion, Diazinon, and Glyphosate, The Lancet 16, 490 (2015), https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(15)70134-8/abstract

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Statement by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine regarding PLOS ONE article on our study of genetically engineered crops, March 1, 2017, https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2017/03/statement-by-the-national-academies-of-sciences-engineering-and-medicine-regarding-plos-one-article-on-our-study-of-genetically-engineered-crops

A.P. Taylor, National Academies Revise Conflict of Interest Policy, The Scientist, May 3, 2017, https://www.the-scientist.com/national-academies-revise-conflict-of-interest-policy-31564

P. Beyer, Golden Rice and ‘Golden’ Crops for Human Nutrition, Nature Biotechnology 27, 478 (2010), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20478420/

ISAAA, The Golden Rice Technology, https://www.isaaa.org/kc/inforesources/biotechcrops/the_golden_rice_technology.htm

G. Tang, et al., Beta-carotene in Golden Rice is As Good As Beta-carotene in Oil at Providing Vitamin A to Children, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (retracted article) 96, 658 (2012), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22854406/

Project Management Institute, https://www.pmi.org/

R. McKie, ‘A Catastrophe’: Greenpeace Blocks Planting of ‘Lifesaving’ Golden Rice, The Guardian, May 25, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/may/25/greenpeace-blocks-planting-of-lifesaving-golden-rice-philippines

International Rice Research Institute, Golden Rice FAQs, https://www.irri.org/golden-rice-faqs

A. Wilson, Goodbye to Golden Rice? GM Trait Leads to Drastic Yield Loss and “Metabolic Meltdown”, Independent Science News, Oct. 25, 2017, https://www.independentsciencenews.org/health/goodbye-golden-rice-gm-trait-leads-to-drastic-yield-loss/

Golden Rice Project, Golden Rice is Part of the Solution, https://www.goldenrice.org/

Union of Concerned Scientists, Gone to Seed, Sept. 11, 2004, https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/gone-seed

DebunkingDenial, Still Deniers After All These Years: A Review of the Heartland Institute’s ‘Climate at a Glance’, https://debunkingdenial.com/still-deniers-after-all-these-years-a-review-of-the-heartland-institutes-climate-at-a-glance-part-i/

DebunkingDenial, Climate and Civilization, Part II: Climate-Related Societal Collapse, https://debunkingdenial.com/climate-and-civilization-part-ii-climate-related-societal-collapse/