August 3, 2023

IV. The Role of Climate change in historical societal collapse

Collapse of Bronze Age societies:

What climate change giveth, subsequent climate change can easily taketh away. While global climate has, on average, remained remarkably steady since the end of the Younger Dryas, there have been regional anomalies with profound impacts on emerging civilizations. The first of these is the so-called 4.2-kiloyear event. Archaeological evidence indicates a dramatic shift in precipitation patterns, especially in Africa and South Asia, beginning around 2200 BC.

Precipitation patterns are affected in complex ways not only by ocean temperatures, but also by ocean and atmospheric currents. For example, “The 4.2-kiloyear event resulted in an enormous reduction in the strength of the East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM). This profound weakening of the EASM has been postulated to have resulted from a reduction in the strength of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC).” The AMOC (see Fig. IV.1) “is characterized by a northward flow of warm, salty water in the upper layers of the Atlantic, and a southward flow of colder, deep waters.” A collapse of the AMOC, with disastrous impacts on agricultural production in many regions of the globe, is one of the climate tipping points of present-day concern.

In Africa and parts of Asia, the shift brought about a mega-drought that may have lasted for a few centuries, contributing to the most recent transformation of the previously green Sahara region into a desert, and causing severe negative impacts on agricultural productivity from Egypt, through Mesopotamia, and much of southern Asia (see Fig. IV.2). According to Wikipedia, “Prolonged failure of rains caused acute water shortage in large areas, causing the collapse of sedentary urban cultures in south central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and India, and triggering large-scale migrations. Inevitably, the new arrivals came to merge with and dominate the post-urban cultures.” At the same time, other parts of the globe (blue squares in Fig. IV.2) saw unusually heavy precipitation and flooding.

The 4.2 kyr event has been blamed for the collapse of several long-established civilizations. For example, in Mesopotamia: ““A study of fossil corals in Oman provides evidence that prolonged winter shamal [northwesterly winds causing large sandstorms] seasons, around 4200 years ago, led to the salinization of the irrigated field, which made a dramatic decrease in crop production trigger a widespread famine and eventually the collapse of the ancient Akkadian Empire [the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia, established via conquests by its founder Sargon of Akkad] … Archaeological evidence documents widespread abandonment of the agricultural plains of northern Mesopotamia and dramatic influxes of refugees into southern Mesopotamia, around 2170 BC. A 180-km-long wall, the “Repeller of the Amorites”, was built across central Mesopotamia to stem nomadic incursions to the south. Around 2150 BC, the Gutian people, who originally inhabited the Zagros Mountains, defeated the demoralised Akkadian army, took Akkad and destroyed it around 2115 BC.”

The same mega-drought has been blamed for the collapse of the Old Kingdom in Egypt – the “age of the pyramid builders,” with civilization established around 2700 BC in the Nile Delta and along the Nile floodplains – and of the Liangzhu culture, the last Neolithic jade culture, established around 3300 BC in the Yangtze Delta region of China. And in the Indus Valley, “urban centers…were abandoned and replaced by disparate local cultures because of the same climate change that affected the neighbouring regions to the west. As of 2016, many scholars believed that drought and a decline in trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia caused the collapse of the Indus civilisation. The Ghaggar-Hakra [River] system was rain-fed, and water supply depended on the monsoons. The Indus Valley climate grew significantly cooler and drier from about 1800 BC, which is linked to a contemporary general weakening of the monsoon. Aridity increased, with the Ghaggar-Hakra River retracting its reach towards the foothills of the Himalayas, leading to erratic and less-extensive floods, which made inundation agriculture less sustainable. Aridification reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation’s demise, and to scatter its population eastward.”

Andrew Glikson points out that it is not only these early Bronze Age civilizations that suffered from significant changes in the patterns of droughts and floods: “Across the globe and throughout history the rise and fall of civilisations such as the Maya in Central America [collapse around 900 AD], the Tiwanaku in Peru, and the Khmer Empire in Cambodia [collapse of Angkor in early 1400s], have been determined by the ebb and flow of droughts and floods.”

The General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century in Europe:

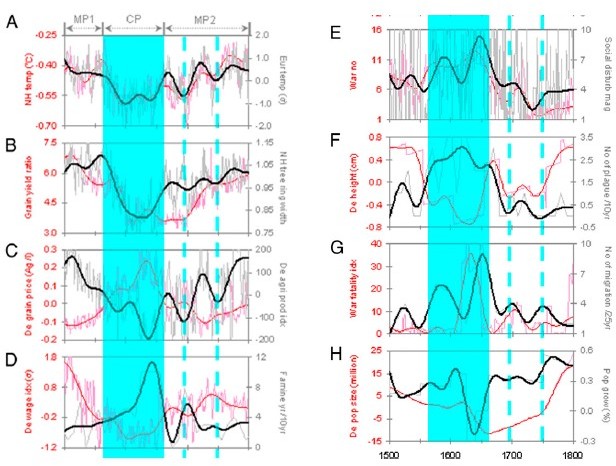

It is possible to make more compelling correlations between recorded (as opposed to archaeologically inferred) historical data characterizing societal distress and climate change revealed by proxy temperature records during the past millennium. For example, Zhang et al. provide Fig. IV.3 showing the correlation between an unusually cold period in Europe from 1560 to 1660 and disastrous impacts on crop production, famine, wars, disease, and population decline. This was in the midst of a period dubbed the Little Ice Age. But this had less of a global than a regional impact; while northern hemisphere average temperatures dropped by perhaps 0.15°C during the affected century, the drop within Europe was about ten times larger.

During the same 100-year period as the temperature drop, agricultural production in Europe fell dramatically, while grain prices rose; famine years per decade nearly tripled; the number of wars doubled; the number of plagues per decade grew by nearly a factor of five; migration rates doubled; and a previously growing European population went into decline. This period in Europe is normally dubbed the General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century. Episodes of social instability track the cooling trend with a time lag up to 15 years.

Clearly, additional events were at play, but the climate change was, if not the ultimate causal factor, at the very least a critically important threat multiplier. For example, the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) may have started as a war of succession to the Bohemian throne, but it was undoubtedly exacerbated by the ongoing human crises of the period. Further fueled by animosity between Catholics and Protestants, it escalated to a conflict involving all major European powers. Germany was particularly devastated and population there dropped by as much as 70% in parts of the Holy Roman Empire.

21st-Century Syrian Civil War:

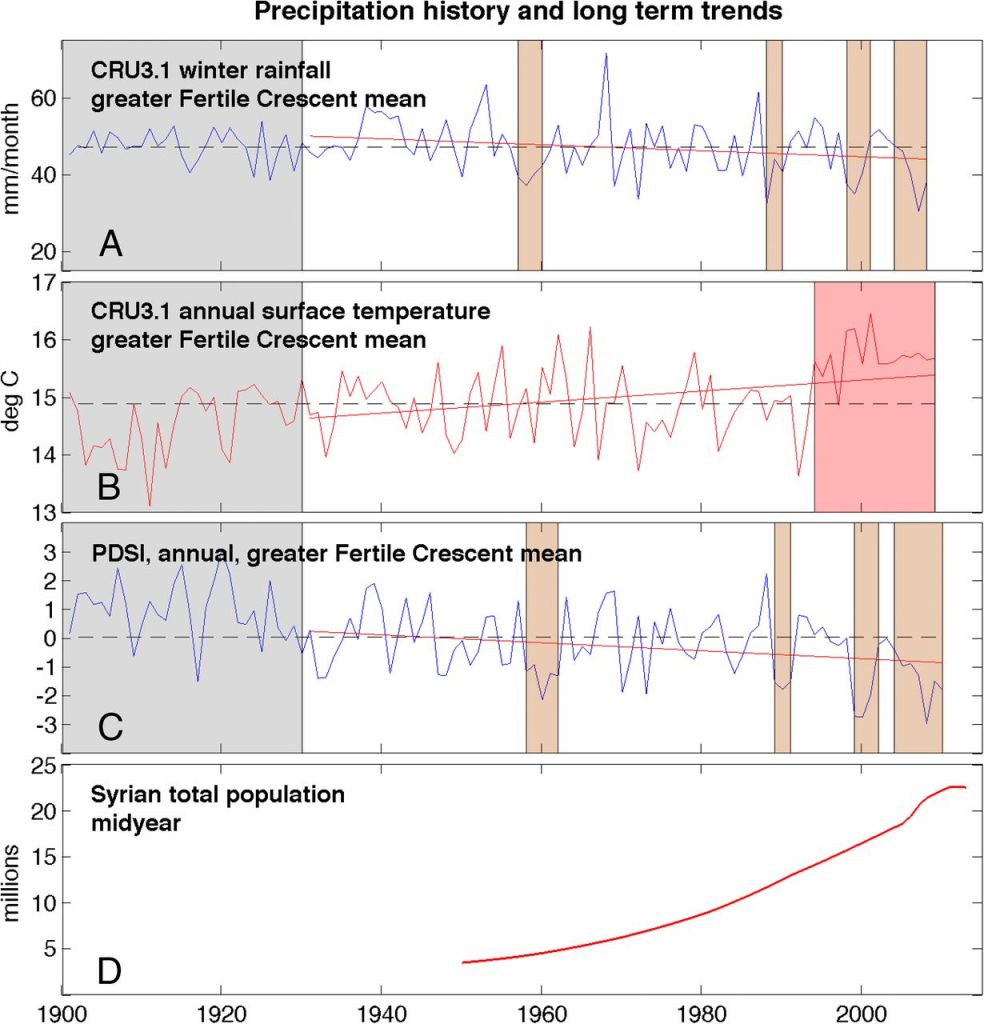

As ocean and atmospheric currents shift, different regions of the globe see increased precipitation or increased drought. Today, fueled by human-caused global warming, these patterns are revealed by satellite measurements, such as those from NASA in Fig. IV.4. There we can see that the Fertile Crescent, the site of early civilizational collapse from the droughts of the 4.2-kyr event, is once again suffering from intense drought. This can be seen in more detailed data for the Fertile Crescent, shown in Fig. IV.5. During the current century, surface temperatures are higher, winter rainfall lower, and droughts more severe than the long-term averages. The recent changes may seem small on graphs such as Fig. IV.5, but the impacts, especially when coupled with the rapidly growing Syrian population (lower frame), have been catastrophic.

The local climate change in the Fertile Crescent indicated in Figs. IV.4 and IV.5 undoubtedly played an important role in the Syrian Civil War that began in 2011. A multi-year severe drought beginning in 2006-7 (indicated by the rightmost brown shaded band in frame C of Fig. IV.5) led to the collapse of agricultural productivity in the northeastern “breadbasket” region of Syria, which had traditionally produced over two thirds of the country’s crop yields. Between 2007 and 2008, wheat, rice and feed prices in Syria more than doubled. By the winter of 2010 the drought had obliterated nearly all of the livestock herds in the country. In the northeast provinces, nutrition-related diseases increased rapidly and school enrollments dropped by as much as 80%. The crisis was exacerbated by President Bashar al-Assad’s decision to liberalize the economy by cutting food and fuel subsidies on which many Syrians had become dependent.

What followed was a mass migration of roughly 1.5 million people from rural farming areas to the peripheries of urban centers. The burden on Syria’s cities was high to begin with, as a result of population growth of roughly 2.5%/year and an additional influx of 1.2-1.5 million Iraqi refugees. Kelley, et al. report that “The total urban population of Syria in 2002 was 8.9 million but, by the end of 2010, had grown to 13.8 million… The rapidly growing urban peripheries of Syria, marked by illegal settlements, overcrowding, poor infrastructure, unemployment, and crime, were neglected by the Assad government and became the heart of the developing unrest… Thus, the migration in response to the severe and prolonged drought exacerbated a number of the factors often cited as contributing to the unrest, which include unemployment, corruption, and rampant inequality.” The Syrian situation provides an object lesson in how mass migrations driven by climate change and agricultural failures can add extreme burdens that tip previously stable urban areas into dangerous instability.

When the rebellions in Syria exploded into full-fledged Civil War, the impacts spread into Europe, and quite possibly beyond. The influx of Syrian refugees has spurred the rise of right-wing anti-immigrant populism in Europe and possibly in the U.S. These populist movements, in turn, have increased the threat of violent internal instability in countries that were not affected by the climate anomalies that triggered the Syrian unrest. But since other impacts of human-caused global warming are by now being felt worldwide, we may well be in the midst of a 21st-century illustration of how climate change can contribute to societal collapse. In particular, the severe drought conditions in the once Fertile Crescent continue, sparking tensions over scarce water supplies. With Syria as a template, what used to be known as the “Cradle of Civilization” could turn into the “Coffin of Civilization” if global warming continues throughout this century.

V. worst-case future scenarios

The Syrian collapse is our first example of societal crises exacerbated by human-caused climate change. One may think that current human societies are so much further advanced technologically than collapsed societies through history that first-world countries are no longer so susceptible to the ravages of changing climate, drought and floods, etc. One counterpoint to that thought is that we live in a much more interconnected world today, where what might previously have been local or regional crises now have international impacts. The Syrian Civil War, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War are three recent examples. Another counterpoint is that Nature has shown repeatedly that it can overpower human defenses.

Furthermore, Earth’s climate is highly nonlinear and disasters can turn deadly unexpectedly rapidly. Greenland and polar ice sheets are already melting faster than the most pessimistic of the early climate model predictions. As they melt, they cause local ocean temperature changes that can alter the flow of ocean currents – as was the speculated cause of the Younger Dryas period — that modern agriculture relies on. Ocean current shifts can lead to floods and droughts in areas that have not experienced them in recent history. And that can lead, in turn, to the sort of agricultural failures that trigger social stresses.

Climate scientists have tried for years to raise awareness of a host of possible tipping points in the climate (see Fig. V.1) – changes that become irreversible at some point, no matter what mitigating policies are put into effect after the tipping point has been reached. We are already close to – if we haven’t actually passed – tipping points for the melting of polar ice and for the collapse of coral reefs worldwide. The collapse of coral reefs will seriously impact the food chain in the oceans, and eventually of humans, as well. Furthermore, the passing of some tipping points can accelerate the approach to others, as suggested by the interaction arrows in Fig. V.1. For example, melting of the Greenland and West Antarctic Ice Sheets could well disrupt the Atlantic Ocean Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), the same current whose past disruption was a likely cause of the 4.2-kyr event and the collapse of numerous early human cities. One very recent analysis estimates that an AMOC collapse into a much weaker state could occur well within the current century, with major impact on worldwide climate conditions.

Surpassing some tipping points can further accelerate global warming. For example, as the Arctic permafrost thaws, carbon dioxide and methane currently buried beneath the permafrost would be released to the atmosphere, adding to Earth’s thermal blanket. That, in turn, could lead to more intense droughts, to the loss of greenery and widespread forest fires in the Amazon rainforest, which reduce the Earth’s absorption of CO2 and thereby further increase global warming.

In order to avoid appearing alarmist, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has devoted little serious attention in its assessment reports to the possibility of societal collapse resulting from global warming. But various groups have recently attempted to model how a worst-case scenario might unfold in the future as a result of human-caused global warming. For example, an international group of scholars has recently published an article entitled “Climate Endgame: Exploring Catastrophic Climate Change Scenarios” in order to inform risk assessments for continuing on our current fossil-fuel burning path. As the authors point out: “Knowing the worst cases can compel action, as the idea of ‘nuclear winter’ in 1983 galvanized public concern and nuclear disarmament efforts.”

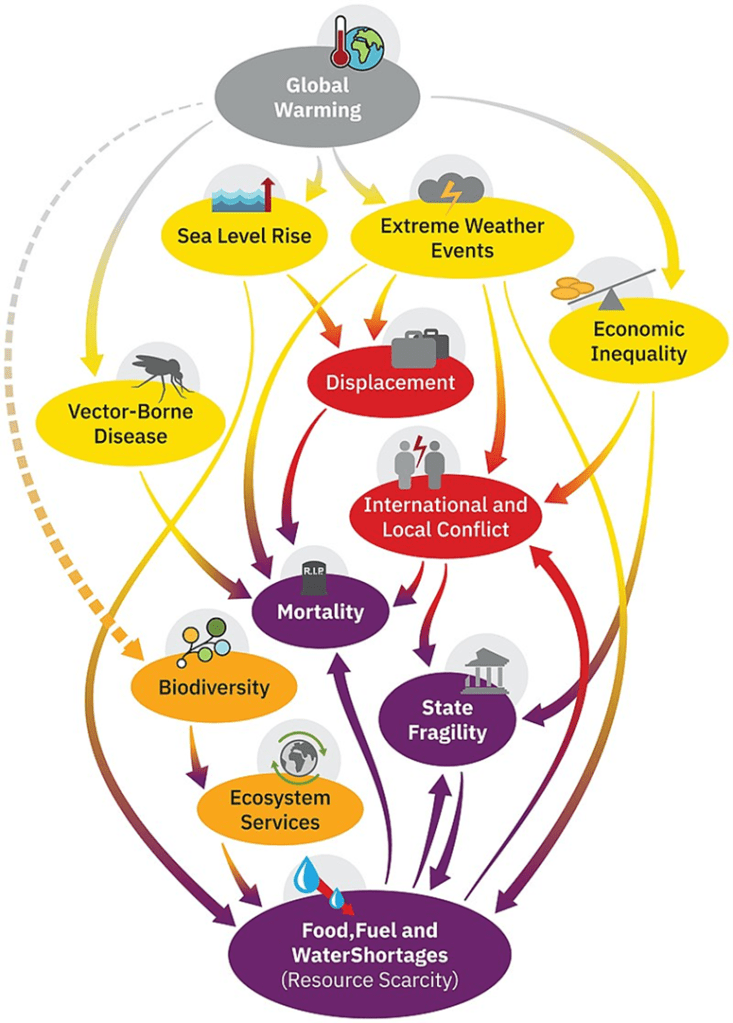

Kemp, et al. point out that “A thorough risk assessment would need to consider how risks spread, interact, amplify, and are aggravated by human responses.” The tipping cascades mentioned above are the first mechanism they consider for such amplification. As for aggravation by human responses, the authors offer the following warnings, in addition to the warnings from human history we have described in Section IV: “Second, climate change could directly trigger other catastrophic risks, such as international conflict, or exacerbate infectious disease spread, and spillover risk. These could be potent extreme threat multipliers. Third, climate change could exacerbate vulnerabilities and cause multiple, indirect stresses (such as economic damage, loss of land, and water and food insecurity) that coalesce into system-wide synchronous failures. This is the path of systemic risk. Global crises tend to occur through such reinforcing ‘synchronous failures’ that spread across countries and systems, as with the 2007–2008 global financial crisis…It is plausible that a sudden shift in climate could trigger systems failures that unravel societies across the globe.”

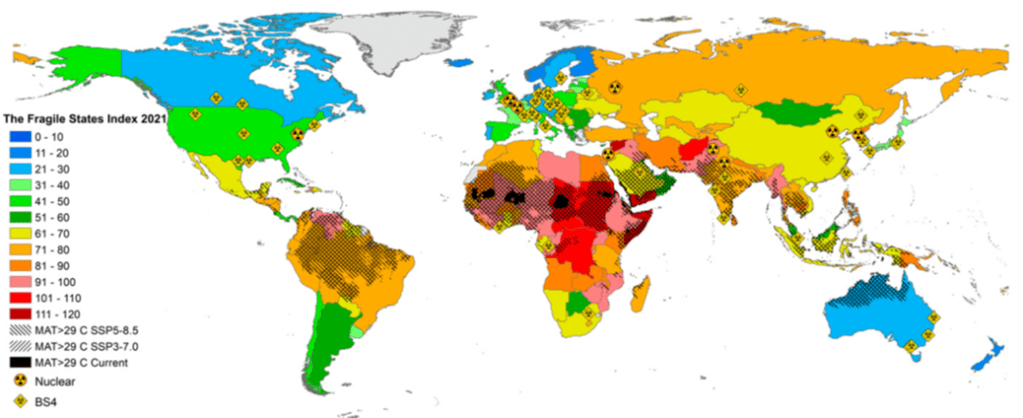

As an aid in assessing risks for how human aggravation could make climate change catastrophic, Kemp, et al. offer the map in Fig. V.2. In that map, the cross-hatched regions are those that are projected to exceed mean annual temperatures of 29°C by 2070, in IPCC scenarios in which global annual mean temperatures reach about 3.0°C above pre-industrial levels by 2070. Temperature extremes in these regions will exceed those for which humans have evolved to live comfortably. By 2070 it is projected that 2 billion people will live within these regions, which include much of India, West Africa, and north central South America. The color-coding of countries in the map indicates values of the Fragile States Index (FSI), a measure of current state instability. The map then shows substantial overlap between projected extreme heat and countries whose governments are unstable. To add further potential risks, the map also indicates the capitals of states with nuclear weapons and the locations of maximum containment Biosafety Level 4 laboratories, which handle the most dangerous pathogens in the world.

The choice of 3°C warming by the end of this century as the scenario that might lead to worst-case impacts relies on the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, which rates the risks at this level of warming as “high” or “very high” for all five of the group’s primary concerns: (1) unique and threatened ecosystems; (2) frequency and severity of extreme weather events; (3) global distribution and balance of impacts; (4) total economic and ecological impact; (5) irreversible, large-scale, abrupt transitions (i.e., passing tipping points). If global temperatures rise by 3°C or more this century, we will enter a climate regime in which human societies have never previously existed. The diagram in Fig. V.3 shows the potential interacting systems and concerns that could be triggered by such warming.

Kemp, et al. describe some of the concerns encompassed in Fig. V.3 this way: “Societal risk cascades could involve conflict, disease, political change, and economic crises. Climate change has a complicated relationship with conflict, including, possibly, as a risk factor…especially in areas with preexisting ethnic conflict [as in Syria]. Climate change could affect the spread and transmission of infectious diseases, as well as the expansion and severity of different zoonotic infections, …creating conditions for novel outbreaks and infections… Epidemics can, in turn, trigger cascading impacts, as in the case of COVID-19…Other important modern-day vulnerabilities include the rapid spread of misinformation and disinformation. These epistemic risks are serious concerns for public health crises…and have already hindered climate action.”

A study of Earth and human history helps to illuminate some of the potentially disastrous interactions triggered by continuing global warming, as summarized in a Wikipedia article on “climate apocalypse”:

- Severe ecosystem changes – Elevated global temperatures and high carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere and the oceans tend to deplete oxygen levels in the oceans. Five of Earth’s past mass extinction events appear to have been correlated with rapid CO2 and methane release to the atmosphere from massive volcanic eruptions, causing oxygen-depleted oceans. As summarized by Wikipedia: “Geoscientists have found that anaerobic microbes would have thrived in these conditions and produced vast amounts of hydrogen sulfide gas. Hydrogen sulfide is toxic, and its lethality increases with temperature. At a critical threshold, this toxic gas would have been released into the atmosphere, causing plant and animal extinctions both in the ocean and on land. Models suggest that this would also have damaged the ozone layer, exposing life on Earth to harmful levels of UV radiation. Deformities found in fossil spores in Greenland provides evidence that this may have occurred during the Permian extinction event… During the Permian–Triassic extinction event 250 million years ago, the Earth was approximately 6°C hotter than the pre-industrial baseline. At this time, 95% of living species were wiped out and sea life suffocated due to a lack of oxygen in the ocean.” A massive ocean die-off would dramatically alter food chains on Earth and threaten societal stability.

- Increased disease exposure – Insects carrying infectious diseases are already moving into regions of the globe that were inhospitable to them only a decade ago. For example, the mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) whose bites transmit Zika (which can cause devastating birth defects), dengue fever and yellow fever cannot survive or breed in cold winters. As a consequence, those diseases have seen outbreaks previously mostly in equatorial climates. But these diseases have already infected many people in southern U.S. states and the mosquitoes have been found as far north as Nevada, Utah and Nebraska over the past few years. They are expected to move northward as global warming continues. A similar trend has been seen as West Nile virus has infected citizens in Texas. In addition to diseases borne by insects, an increased incidence of severe weather and floods and of food scarcity are expected to aid the spread of viral epidemics. Furthermore, “melting permafrost also threatens to release diseases that have been dormant for many years, as was the case in August 2016 when a thawed reindeer carcass that was almost a century old infected several individuals in Siberia with anthrax.”

- Reduced crop yields – As ocean and atmospheric currents weaken and shift with warming global temperatures, patterns of flooding and drought will intensify. Most of the historical climate-induced civilization collapses we covered earlier in this post were triggered by drought and agricultural failures, which led to famines, deaths, wars and mass migrations. Extreme heat and the migration of new crop-endangering pests into new regions of the globe will also contribute to crop shortages, declining human health, and increasing societal stress.

- Deadly heat waves – A European heat wave in the summer of 2003 caused more than 70,000 additional human deaths, compared to the immediately preceding years. In 2015, a heat wave in Karachi, Pakistan raised temperatures above 45°C and caused 2,000 deaths. As worldwide human populations continue to grow older, on average, their ability to weather extreme heat events will diminish. And extreme heat events will only increase in frequency as global warming continues.

- Mass migration – Sea level rise is accelerating as a result of global warming. If tipping points are passed for the eventual melting of the Greenland and polar ice sheets, sea levels could rise as much as 40 meters over the next several centuries. Rising sea levels force mass migrations from coastal regions and, as we have seen from the Syrian Civil War, such migrations transmit societal stress to other countries. In addition, “much of the Internet’s key infrastructure is built near coastlines and is not built to be permanently submerged in water.”

- Water shortages – As the Earth and the lower atmosphere warm, overall global rainfall may increase, with greater ocean evaporation and more water held in the warmer atmosphere. But as we saw in Fig. IV.3, some regions of the globe will see increased precipitation, while others see increased drought. The increased drought will not only impact agricultural productivity, but will also deplete fresh water resources. The IPCC’s report on climate Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability estimates that roughly one billion people in dry regions will face increasing drinking water scarcity. Furthermore, many societies worldwide depend on glacial melt for their supply of drinking water. These glaciers are disappearing at accelerating rates as a result of global warming, only increasing global concerns about long-term water shortages.

- Ocean current changes – Ocean current weakening is believed to have been responsible for both the Younger Dryas and 4.2-kiloyear climate events we discussed earlier. Today’s global warming is causing accelerating ice melt from Greenland and this appears already to be disrupting the Gulf Stream that warms many northern regions in North America and Europe. Over the 20th century, analyses of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation – the same current whose disruption is believed to have led to the collapse of Bronze Age civilizations – indicate that the flow has slowed by 15-20%. A critical part of the ”overturning” in that current is the sinking of increased density cold salt water at northern latitudes. But the ice sheet melt adds lower-density cold fresh water to the ocean surfaces, disrupting the circulation. Increasing disruption from increasing Earth temperatures, culminating in a collapse of the current as early as this century, will exacerbate regional differences in temperatures, storm activity, precipitation and drought patterns.

It is essential to keep in mind the nonlinear behavior of Earth’s climate when it is forced out of equilibrium. There are many positive feedback effects that reinforce warming triggered by greenhouse gas emissions. As ice sheets and glaciers melt, less sunlight is reflected into space by Earth’s surface, and the heating is increased. As the permafrost melts and as the oceans warm, they release more methane and CO2 into the atmosphere and thereby enhance the warming. The warmer atmosphere holds more water, but water vapor itself is a heat-trapping greenhouse gas. Increased droughts lead to an increased frequency of forest fires that reduce biological uptake of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Warming soil increases microbial respiration, which releases more CO2 to the atmosphere. And, as was shown in Fig. V.1, when one climate tipping point is surpassed, this may well accelerate the approach to other tipping points. Humans have already driven Earth’s climate to a state in which these positive feedback mechanisms appear to dominate over negative feedbacks – e.g., the absorption of CO2 from the atmosphere by forests, land and oceans – that have historically maintained the stability of the Holocene climate.

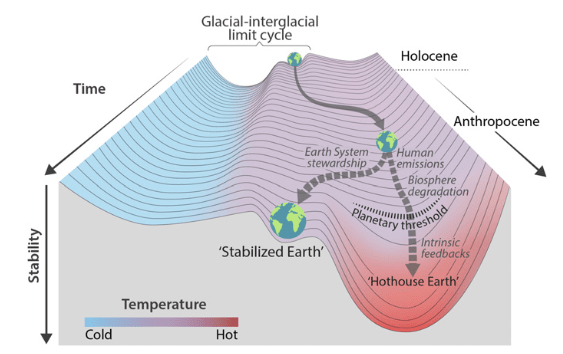

A paper published in 2018, entitled Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene, has raised the possibility that there is a threshold – realistically reachable in the 21st century –beyond which all of these self-reinforcing warming trends can drive the Earth’s climate into a new, much warmer, equilibrium state they label the “Hothouse Earth,” from which it would be extremely difficult to recover. The ”Anthropocene” is the proposed new geological epoch in which “human activity now rivals geological forces in influencing the trajectory of the Earth System.” Figure V.4, reproduced from the “Hothouse Earth” paper, illustrates two possible trajectories for Earth’s future climate development from its current human-influenced warm conditions.

In Fig. V.4, valleys represent stable, and therefore typically long-lasting, climate conditions, while peaks are unstable conditions from which the climate changes readily in response to any forcing. Blue regions are those where global temperatures are colder than the pre-industrial average, and purple-to-red regions are those with hotter temperatures. The left half of the figure represents the range of conditions that has characterized Earth’s million-year-long geologic cycle of Ice Ages and interglacial periods. The right half is terra incognita for humans, where global temperatures exceed those experienced since homo sapiens left Africa some 70,000 years ago.

If humans do not get their act together quickly enough to eliminate fossil fuel burning and to take active measures to restabilize the climate, all those self-reinforcing positive feedback mechanisms will eventually drive Earth’s climate toward a hothouse state that “poses severe risks for health, economies, political stability…(especially for the most climate vulnerable), and, ultimately, the habitability of the planet for humans.” Guided by our reading of human prehistory and history, described in this post, such a runaway climate would undoubtedly lead to the collapse of multiple human societies over the coming centuries.

VI. summary

The birth and maintenance of human civilization has relied on a largely stable Earth climate emerging from the last Ice Age. The development of farming and the domestication of animals provided reliable food supplies, without the need for nomadic hunting and gathering, that allowed the first sizable cities to accumulate in naturally fertile regions some 6000 years ago. The rise of agriculture did not lead automatically to the kingdoms and states with hierarchical governments that we often associate with early human history, but these seem rather to have resulted from conquests by a new class of wealth-seeking Bronze Age warriors outfitted with new metal weapons.

A number of societal collapses or severe crises throughout human history have been triggered by persistent changes in regional climate. Sometimes century-long droughts and sometimes century-long cold spells have decimated agricultural productivity, leading in turn to famine, wars, the spread of disease, mass migrations, and many human deaths. We have described as examples the collapse of Bronze Age societies in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley and the Yangtze Valley, and the General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century in Europe. A more recent example, driven now by human-induced global warming, has occurred in the Syrian Civil War beginning in 2011.

We are now living in an epoch when human activities have raised global temperatures to the upper limits of those survived by previous human societies. If global temperatures continue on the current trajectory to rise by 3°C or more (above pre-industrial levels) this century, we will enter a regime in which human societies have never existed previously. Positive feedback mechanisms in the Earth system could then trigger a cascade of disastrous changes to ice sheets, ocean currents, sea levels, forests, permafrost, and severe weather events that lead to an irreversible transition to a new, stable “hothouse” state of the Earth climate. Of particular concern is a potential weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, an ocean current that normally maintains temperate conditions over much of the globe, and whose weakening in the past likely produced the regional climate changes that doomed so many Bronze Age civilizations.

It is not possible as of now to reliably estimate the probabilities of such cascading failures, but the potential for them must be considered seriously. Humanity seems, for the most part, to be sleepwalking into societal collapse triggered largely, at this point, by the corporate greed of fossil fuel industries, exacerbated by the promotion of disinformation. The level of concern and political will in the countries most responsible for greenhouse gas emissions is currently insufficient to avoid catastrophe; it seems to be based on the bet that the rich will survive what might cause the weak and the poor to succumb. There is, indeed, a growing trend among the super-rich to prepare for the possible collapse of civilization with lavish underground bunkers and rapid get-away plans. But as global resources get stressed, as mass migrations take root, as disease and disaster spread, as food supplies suffer, and as humans respond irrationally to all these threats, all bets are off. Everyone’s safety is threatened. Even if human extinction is avoided, multiple human societies may collapse. We can only hope that the younger generation, who seem much more alert to these dangers, take over global power sooner rather than later.

references:

D. Graeber and D. Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250858801/the-dawn-of-everything

B. Handwerk, How Did Climate Change Affect Ancient Humans?, Smithsonian Magazine, April 13, 2022, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-did-climate-change-affect-ancient-humans-180979908/

Britannica, Climate Change Since the Emergence of Civilization, https://www.britannica.com/science/climate-change/Climate-change-since-the-emergence-of-civilization

E. Sohn, Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations, https://climate.nasa.gov/news/1010/climate-change-and-the-rise-and-fall-of-civilizations/

Wikipedia, Societal Collapse, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Societal_collapse

A. Glikson, Climate and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations: A Lesson from the Past, The Conversation, Dec. 10, 2015, https://theconversation.com/climate-and-the-rise-and-fall-of-civilizations-a-lesson-from-the-past-51907

D. Steel, C.T. DesRoches, and K. Mintz-Woo, Climate Change and the Threat to Civilization, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, e2210525119 (2022), https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2210525119

L. Kemp, et al., Climate Endgame: Exploring Catastrophic Climate Change Scenarios, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, e2108146119 (2022), https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.2108146119

Wikipedia, Recent African Origin of Modern Humans, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recent_African_origin_of_modern_humans

Wikipedia, Interbreeding Between Archaic and Modern Humans, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interbreeding_between_archaic_and_modern_humans

S. Walters, How Humans Survived the Ice Age, Discover Magazine, Dec. 9, 2021, https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/how-humans-survived-the-ice-age

Wikipedia, Holocene, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holocene

Wikipedia, Pleistocene, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pleistocene

Wikipedia, Neolithic, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neolithic

https://debunkingdenial.com/ten-false-narratives-of-climate-change-deniers-part-i/

https://debunkingdenial.com/ten-false-narratives-of-climate-change-deniers-part-ii/

J.D. Shakun, et al., Global Warming Preceded by Increasing Carbon Dioxide Concentrations During the Last Deglaciation, Nature 484, 49 (2012), https://www.nature.com/articles/nature10915

Britannica, Younger Dryas, https://www.britannica.com/science/Younger-Dryas-climate-interval

Britannica, Thermohaline Circulation, https://www.britannica.com/science/thermohaline-circulation

Wikipedia, Fertile Crescent, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fertile_Crescent

Wikipedia, Holocene Climatic Optimum, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holocene_climatic_optimum

G. Beyer, Human Civilization’s First Cities: 6 of the Oldest, The Collector, May 18, 2023, https://www.thecollector.com/first-cities-human-civilization-oldest-cities/

Wikipedia, Neolithic Revolution, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neolithic_Revolution

S. Gulyás, et al., Intensified Mid-Holocene Floods Recorded by Archeomalacological Data and Resilience of First Farming Groups of the Carpathian Basin, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 12, article #170 (2020), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-020-01120-3

Sea Level in the Past 20,000 Years, https://www.e-education.psu.edu/earth107/node/1506

Wikipedia, Code of Hammurabi, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Hammurabi

Wikipedia, Epic of Gilgamesh, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epic_of_Gilgamesh

Wikipedia, 4.2-Kiloyear Event, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/4.2-kiloyear_event

Wikipedia, Sahara, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sahara

S. Kaboth-Bahr, et al., A Tale of Shifting Relations: East Asian Summer and Winter Monsoon Variability During the Holocene, Scientific Reports 11, article #6938 (2021), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-85444-7

Wikipedia, Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlantic_meridional_overturning_circulation

NOAA, What Is the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)?, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/amoc.html

S. Kaplan, Scientists Detect Sign That a Crucial Ocean Current is Near Collapse, Washington Post, July 25, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/07/25/atlantic-ocean-amoc-climate-change/

P. Ditlevsen and S. Ditlevsen, Warning of a Forthcoming Collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, Nature Communications 14, article #4254 (2023), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-39810-w

L.B. Railsback, et al., The Timing, Two-Pulsed Nature, and Variable Climatic Expression of the 4.2 ka Event: A Review and New High-Resolution Stalagmite Data from Namibia, Quaternary Science Reviews 186, 78 (2018), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S027737911731003X?via%3Dihub

D.D. Zhang, et al., The Causality Analysis of Climate Change and Large-Scale Human Crisis, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 17296 (2011), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3198350/

Wikipedia, Little Ice Age, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Ice_Age

Wikipedia, The General Crisis, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_General_Crisis

Wikipedia, Thirty Years’ War, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thirty_Years%27_War

Wikipedia, Holy Roman Empire, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holy_Roman_Empire

NASA, Warming Makes Droughts, Extreme Wet Events More Frequent, Intense, Mar. 13, 2023, https://www.nasa.gov/feature/warming-makes-droughts-extreme-wet-events-more-frequent-intense

C.P. Kelley, S. Mohtadi, M.A. Cane, and Y. Kushnir, Climate Change in the Fertile Crescent and Implications of the Recent Syrian Drought, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 3241 (2015), https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1421533112

Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/climate-data/palmer-drought-severity-index-pdsi

A.J. Rubin, A Climate Warning from the Cradle of Civilization, New York Times, July 29, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/29/world/middleeast/iraq-water-crisis-desertification.html

W. Steffen, J. Rockström, K. Richardson, and H.J. Schelinhuber, Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, 8252 (2018), https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1810141115

N. Wunderling, J.F. Donges, J. Kurths, and R. Winkelmann, Interacting Tipping Elements Increase Risk of Climate Domino Effects Under Global Warming, Earth System Dynamics 12, 601 (2021), https://esd.copernicus.org/articles/12/601/2021/

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, http://www.ipcc.ch/

IPCC, AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/

IPCC Working Group II, Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, https://www.ipcc.ch/working-group/wg2/?idp=180

Wikipedia, Nuclear Winter, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_winter

N. Haken, et al., Fragile States Index 2022 – Annual Report, https://fragilestatesindex.org/2022/07/13/fragile-states-index-2022-annual-report/

Wikipedia, Climate Apocalypse, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Climate_apocalypse

Wikipedia, Anoxic Event, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anoxic_event

M. McKenna, Why the Menace of Mosquitoes Will Only Get Worse, New York Times Magazine, April 20, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/20/magazine/why-the-menace-of-mosquitoes-will-only-get-worse.html

Yale Climate Connections Team, Mosquito That Can Carry Viral Infections Spreads Northward in U.S., June 28, 2023, https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2023/06/mosquito-that-can-carry-viral-infections-spreads-northward-in-u-s/

M. Doucleff, Anthrax Outbreak in Russia Thought to be Result of Thawing Permafrost, NPR, Aug. 3, 2016, https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2016/08/03/488400947/anthrax-outbreak-in-russia-thought-to-be-result-of-thawing-permafrost

J.-M. Robine, et al., Death Toll Exceeded 70,000 in Europe During the Summer of 2003, Comptes Rendus Biologies 2008, 171, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18241810/

K. Haider and K. Anis, Heat Wave Death Toll Rises to 2,000 in Pakistan’s Financial Hub, Bloomberg News, June 24, 2015, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-06-24/heat-wave-death-toll-rises-to-2-000-in-pakistan-s-financial-hub#xj4y7vzkg

S. Connor, Gulf Stream is Slowing Down Faster Than Ever, Scientists Say, The Independent, Mar. 23, 2015, https://www.independent.co.uk/climate-change/news/gulf-stream-is-slowing-down-faster-than-ever-scientists-say-10128700.html

E. Osnos, Doomsday Prep for the Super-Rich, The New Yorker, Jan. 22, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/01/30/doomsday-prep-for-the-super-rich