August 11, 2025

I. introduction

Millennial angst is alive and well a quarter of the way through the new century. One manifestation is a spate of recent articles, videos, and books arguing that science, as a broad field, is stagnating, or slowing down, or becoming less disruptive, or losing its usefulness, or getting less bang for its buck, or just simply coming to an end. We will argue here that this hand-wringing is often based on too narrow a perception of science, one informed in large part by Thomas Kuhn’s philosophical work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Kuhn argued basically that real advances in science (although not necessarily converging on some ultimate “truth”) come through occasional dramatic shifts in the paradigm, the underlying language and framework for interpreting results in a given scientific subfield. What happens in between is largely “mopping up” or workmanlike “puzzle solving” that only serve to reinforce the prevailing paradigm. In Section II, we will present what we consider seven real scientific and technical revolutions that have occurred over the past half-century, which without overthrowing central paradigms have nonetheless had profound impact on both our understanding of nature and the lives of humans.

The different “stagnation” authors use disparate arguments but they support a common, though highly flawed, narrative, one with potentially significant implications for science policy. John Horgan, earlier a staff writer for Scientific American, implies in his 1998 book The End of Science (Fig. I.1) that scientists have already solved the important solvable problems: “Scientists have also stitched their knowledge into an impressive, if not terribly detailed, narrative of how we came to be…given how far science has already come, and given the physical, social, and cognitive limits constraining further research, science is unlikely to make any significant additions to the knowledge it has already generated.” Horgan seems uninterested in actually pinning down details of that “not terribly detailed” narrative. He reinforced his claims in a new preface for the 2015 edition of his book, although by 2023 he himself admitted to second thoughts about his book and former opinion.

Peter Thiel, introduced by New York Times columnist Ross Douthat in a recent interview (Fig. I.2) as “the most influential right-wing intellectual of the last 20 years,” – not to mention Silicon Valley billionaire venture capitalist and guru to Vice President JD Vance – argues quite differently that we have lost our nerve, that we’re too risk-averse to complete the big projects like curing Alzheimer’s disease or establishing immortality. Well, if you expect magic, you’re likely to come away disappointed by science. Thiel also seems to conflate scientific ambition with political will: “a moonshot in the ’60s still meant that you went to the moon. A moonshot now means something completely fictional that’s never going to happen…” Not surprisingly, then, he has decided that scientific ambition has been declining since right after the first moon landing in 1969.

In a 2011 article in The Atlantic entitled The End of the Future, Thiel admitted that it was exceedingly difficult to measure scientific progress “given how complex, esoteric, and specialized the many scientific and technological fields have become.” Nonetheless, he proceeded to justify his pessimism by decrying the lack of any significant progress for decades on technical issues that have actually progressed quite a bit since 2011: higher-speed travel (Blue Origin rocket trips for civilians), renewable energy costs (getting cheaper all the time), nuclear power (lots of progress on small modular fission reactors and even on fusion power), curing cancer and Alzheimer’s disease (considerable progress on both). His article becomes mainly a cautionary tale about predicting the future – Thiel is not particularly good at this.

Sabine Hossenfelder supports her opinion that science is being suffocated by its increasing complexity with reference to a number of recent attempts to quantify the extent to which scientific innovation is slowing down. The only problem, as we’ll show in Section III, is that these attempts at quantification are deeply flawed; they devise metrics whose trends tell you a lot about the shortcomings of the metrics and rather little about the state of science. Patrick Collison and Michael Nielsen make a basic argument about diminishing returns on investment (an issue we will address in Section IV of this post) in science, although the methodology they use to determine the rate of progress is subject to similar flaws as the ones Hossenfelder relies on.

Arguments akin to Horgan’s were made by some prominent physicists toward the end of the 19th century. Horgan argues in his book that there is no historical record of such 19th century skepticism, but there is. For example, Nobel Prize-winning physicist Max Planck described in a late-career talk the discouragement his advisor at the University of Munich, Philipp von Jolly, gave him in 1878 against choosing theoretical physics as a career. von Jolly was a well-respected physicist of his era. Planck said:

“As I began my university studies I asked my venerable teacher Philipp von Jolly for advice regarding the conditions and prospects of my chosen field of study. He described physics to me as a highly developed, nearly fully matured science, that through the crowning achievement of the discovery of the principle of conservation of energy it will arguably soon take its final stable form. It may yet keep going in one corner or another, scrutinizing or putting in order a jot here and a tittle there, but the system as a whole is secured, and theoretical physics is noticeably approaching its completion to the same degree as geometry did centuries ago. That was the view fifty years ago of a respected physicist at the time.”

No physicist at the end of the 19th century could have conceived of the revolutions that were to come in the early 20th century, nor of Planck’s essential role in the quantum revolution. Planck was pulling on a loose thread in classical physics, the complete lack of understanding of the observed spectrum of thermal radiation emitted by a black body at finite temperature. He was able to solve this puzzle only by assuming that the energy of vibrating atoms within the body was quantized, i.e., could only take on certain regularly spaced discrete values. This was the initial step on a path that, over the next quarter-century, led to the paradigm shift of Quantum Mechanics and an advanced understanding of atomic structure and emissions. In parallel with that development, Einstein was developing the Special and General Theories of Relativity. The two parallel paths were partially merged by Paul Dirac into relativistic quantum mechanics in 1928. Quantum Mechanics and Special Relativity did not, as Kuhn might have described it, overthrow classical physics and make its language and framework irrelevant. Rather, they modified classical physics in regimes of atomic and subatomic structure and interactions and motion at speeds near that of light. But they did, indeed, involve philosophical paradigm shifts, as we’ll discuss in Section II.

The point is simply that we don’t know what we don’t know. Scientists pull on loose threads and occasionally the entire structure of what we thought we knew unravels. There are numerous worrisome loose threads scientists are working on now. For example, there is a persistent difference in the values one extracts from two different measurement techniques for the fundamental constant (the Hubble constant) that is connected to the rate of expansion of the universe. Will solving this puzzle overthrow much of what we think we know about the evolution of the universe? We don’t know. The Standard Model of particle physics does not yet provide any clear way to understand why all the antimatter that must have been present just after the Big Bang vanished shortly thereafter. Will solving this puzzle lead beyond the Standard Model? We don’t know.

Horgan seems obsessed, and he supports his case by interviewing similarly obsessed high priests of theoretical physics, with seeking “The Answer, a truth so potent that it quenches our curiosity once and for all time.” That sounds to us more like a religious quest than a scientific one. If you’re after religion, again you’re likely to be dissatisfied with science. To be fair, some prominent particle physicists eager to stir the common imagination about their work have inadvisably fed into this quasi-religious vibe. Nobel Prize winner Leon Lederman wrote a book calling the then-predicted but undiscovered Higgs boson The God Particle. Well, the Higgs boson was discovered in experiments at the Large Hadron Collider in CERN, Geneva in 2012. Once you’ve detected God, what’s left to do? Prominent theorists working on the very important problem of combining the theory of gravity with quantum mechanics have said they’re searching for The Theory of Everything. Well, it’s not a theory of “everything,” it’s a theory goal that would provide a common framework for understanding all the fundamental forces of nature. But that leaves a vast swath of natural phenomena still to be understood. And the pursuit of that so-called Theory of Everything has ended up leading many theoretical physicists into a quasi-religious cul-de-sac where testable predictions are considered “old school.”

The vast majority of working scientists are not obsessed with seeking The Answer. We’re trying to advance our understanding of nature while also trying to improve life on Earth. We’re following our noses, pulling on loose threads in current understanding, trying to solve puzzles that are invariably raised by each new discovery. Some of us are inventing new techniques and new technology that facilitate measurements of unprecedented scope, resolution, or precision. And the cumulative impact of such “normal science,” as Kuhn dubbed it, can be revolutionary. It can dramatically advance our understanding of some set of natural phenomena or the technology available to humans.

II. recent scientific revolutions

Going beyond Kuhn:

Thomas Kuhn considered revolutions in science to be those radical changes that so overturn language and understanding that they render earlier explanations as no longer relevant. Such paradigm shifts are historically few and far between, and only a small fraction of them really become “incommensurate” (Kuhn’s term) with past theories and narratives.

Nicolaus Copernicus started a paradigm shift in 1543 when he proposed that he could explain motions of the planets more easily than former contrived models by assuming that the Earth and other planets all orbited the Sun, rather than the Sun and other planets orbiting the Earth. This was viewed by the Church as an anti-Biblical view and it only became accepted as the new paradigm over centuries, supported in 1610 by Galileo’s astronomical observations with his newly invented telescope, and then definitively by Isaac Newton’s late 17th century development of Laws of Motion and of Universal Gravitation. Both Copernicus and Newton certainly initiated scientific paradigm shifts.

Charles Darwin’s 1859 treatise On the Origin of Species launched a paradigm shift by suggesting that species evolved by natural selection, again replacing a Biblical view. The new paradigm in this case was not widely adopted until experimental work in the 1920s and 1930s by Thomas Hunt Morgan and Theodosius Dobzhansky put both inheritance and speciation on a firm genetic footing.

James Clerk Maxwell launched the first of the unification paradigm shifts in the 1860s, when he deduced equations clarifying that the previously disparate fields of electricity, magnetism, and optics were all facets of the same underlying electromagnetic fields. Unification is not incommensurate with previous treatments, but it simplifies them by providing a more fundamental view.

Dmitri Mendeleev’s creation of the periodic table of the elements in 1869 put chemistry on a much firmer basis by demonstrating the repetition of atomic properties across the known elements. The work of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch in the second half of the 19th century clearly established the germ theory of disease as the new paradigm of medicine, replacing the older theory that attributed diseases to miasmas.

While the 19th century may thus be considered productive, the 20th century stands out as a possible historical anomaly in the frequency of establishing profound new scientific paradigms. It began with physics. Albert Einstein developed the Special Theory of Relativity in 1905 and the General Theory of Relativity in 1915, with a spectacular experimental confirmation in 1919. Quantum mechanics was fully developed before the end of the third decade of the century. Neither relativity nor quantum mechanics are truly incommensurate, in Kuhn’s sense, with classical physics. But each represented a truly revolutionary philosophical paradigm. Quantum mechanics taught us that it was no longer possible to predict with certainty the specific outcome of any one experimental trial, but rather only the probabilities of various outcomes. The experimental confirmations of relativity validated Einstein’s postulate that no object could move through space at a speed faster than that of light (although his General Relativity has allowed for expansion of space itself at faster speeds). These developments imposed fundamental limits on attainable knowledge.

20th century paradigm shifts didn’t stop there. The discoveries of the atomic nucleus (1911), the neutron (1932), and much later of quarks and gluons radically transformed our understanding of the fundamental building blocks of matter. Further theoretical unifications combined the quantum field theory of electromagnetism with that of the weak force responsible for radioactive decay (1967) and then with the theory of the strong force binding nuclei (1973) to form the so-called Standard Model of particle physics. The discovery by Edwin Hubble in 1929 that the universe is expanding ended up completely altering our conceptions of the universe and its origin in a likely Big Bang. The development of techniques for dating the age of the Earth and of the universe launched a new frontier in deviations from the timeline of generational history of humans recounted in the Bible. The 1953 discovery by Francis Crick, James Watson and the too-often forgotten Rosalind Franklin of the double helix structure of DNA was the culmination of decades of research establishing the molecular basis of genetics and setting scientists up for the genomic age to be discussed further below. The new paradigms of continental drift and plate tectonics transformed geologic understanding of earthquakes, volcanoes, and the history of the continents.

These Kuhnian paradigm shifts were mostly accomplished by 1970, when Peter Thiel would have us believe that science began to stagnate. But the 20th century scientific developments that have had the most profound impacts on history and human lives are not contained in any of these paradigm shifts but in the “normal science” that proceeds within the paradigmatic frameworks. The discovery of nuclear fission in a German laboratory in December, 1938 led in very short order to the demonstration of nuclear power and nuclear weapons that have altered history. The invention of the transistor at Bell Labs in 1947 launched an era of microelectronics that culminated in personal computers and smart phones owned by a large fraction of humanity. The development of the birth control pill in 1953 ushered in a “Quiet Revolution” of women gaining control of their reproductive choices, entering universities and the workforce in great numbers, and gaining political clout. These developments, too, were worthy of Nobel Prizes – in the case of birth control, the award was in Chemistry in 1939 for Adolf Butenandt, who isolated reproductive hormones that led to the pill. Each of these developments also launched major industries and fueled post-war economic growth in the U.S. and other western countries. The pursuit of fundamental understanding of the universe and of life is a lofty goal worthy of investment. But it is these “normal science” developments that often bring the greatest economic return on investment in science.

In evaluating scientific progress, it is thus essential to go beyond Kuhn’s narrow view of scientific revolutions. Some scientific revolutions are launched by the development of new technology that enables new kinds of experimental studies. Galileo’s invention of the telescope transformed astronomy. The development of vaccines has revolutionized medicine. The invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by American biochemist Kary Mullis in 1983 has transformed the detailed analysis of DNA and facilitated the Human Genome Project and gene-editing. Other revolutions occur when the cumulative impact of a number of breakthrough puzzle-solving accomplishments dramatically advances our understanding of nature or the technology available to transform life on Earth. In this broader view, there are multiple truly important scientific and technical revolutions that have occurred since 1970, giving the lie to claims of scientific stagnation.

Seven scientific and technical revolutions since 1970:

We outline here seven major scientific and technical revolutions that have occurred over the past half-century, indicating numerous milestone developments for each and a few outstanding open questions still being pursued.

The cosmological revolution has dramatically advanced our understanding of the evolution of the universe, while also raising profound questions for the future. Here are some of the most prominent milestones:

- The standard model of particle physics, started in the 1970s but only completed in 2012 with the experimental discovery of the Higgs boson (2013 Nobel Prize in Physics), has provided deep insight into the timeline and stages in the development of matter in the early moments after the Big Bang (see Fig. II.1).

- Precision measurements of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation (2006 Nobel Prize in Physics) have provided insight into the distribution of matter in the universe some 380,000 years after the Big Bang and have constrained the energy budget of the universe, i.e., the contributions to the universe’s total energy that come from normal atomic matter, from radiation, from so-called dark matter, and from dark energy.

- The 1998 observation that the expansion of the universe is accelerating (2011 Nobel Prize in Physics) could not be accommodated in earlier models. It introduced the need for dark energy as a continuous power source, though the microscopic origin of dark energy is not yet understood.

- Discoveries of many exoplanets orbiting distant stars (2019 Nobel Prize in Physics) clarified how many planets must exist even in the neighborhood of our own Milky Way galaxy. These exoplanets are fueling a current search for any that have the appropriate properties and atmosphere to support life.

- The 2015 first detection of gravitational waves (2017 Nobel Prize in Physics) confirmed a century-old prediction of General Relativity and launched a new field of gravitational-wave astronomy. In the years since, gravitational waves have been detected from multiple mergers of distant black holes and neutron stars.

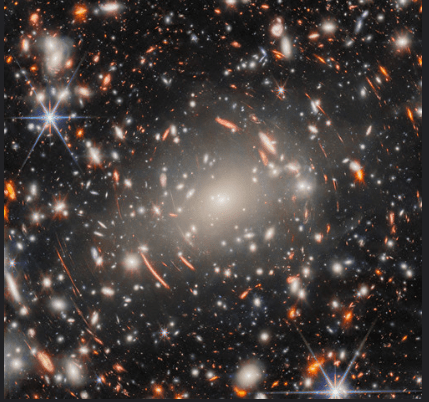

- A new generation of high-resolution telescopes – especially the deep space-based James Webb and the ground-based Vera Rubin telescopes – will provide unprecedented images of galaxies formed early in the universe’s evolution, will enable studies of exoplanet atmospheres to search for signs of life, and will constrain the possible time-dependence of dark energy. A recent deep space image from the James Webb telescope is shown in Fig. II.2.

There are profound open questions in cosmology that will fuel future milestones, for example:

- What are the sources of dark matter and dark energy?

- Will the current discrepancy between measurements of the Hubble Constant from spectra of very distant stars vs. CMB analyses be solved by tweaks to cosmological models or by more dramatic shifts in our understanding?

- Is the expansion of the universe likely to continue accelerating, or will it at some point begin to slow down and possibly even evolve toward contraction?

- Can we detect signatures of the inflationary period proposed to account for the ultra-rapid expansion of the universe in its earliest instants?

- What is the detailed mechanism by which antimatter disappeared in the early seconds after the Big Bang?

- Can General Relativity be combined with quantum theory to allow a better understanding of the beginnings of the universe’s expansion and the inner structure of black holes?

- Will we find exoplanets whose atmospheres bear signatures of life on the planet? Astrophysicists using the James Webb Space Telescope may have already found a first hint in the atmosphere of K2-18b, a large Earth-like planet in the habitable zone of a red dwarf star about 124 light-years away from Earth. The hint consists of the presence in the atmosphere of dimethyl sulfide, a molecule that is produced on Earth only by biological systems such as phytoplankton.

The genomic revolution is fueling research to understand how the properties and disease propensities of individual humans and other animals are influenced by their DNA and is launching an era in which human selection may compete with natural selection as a driver of evolution. The latter development may come to be seen in the future as a paradigm shift in evolution. Here are some of the most prominent genomic milestones:

- The 1983 invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry) to amplify copying of DNA sequences has made genetic testing and genome mapping much more rapid.

- The Human Genome Project succeeded in mapping out the detailed structure of human chromosomes. The same approach has now been applied to many other species, including human predecessors (2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine).

- Curiosity-driven research on bacterial genomes led during this century to the discovery of CRISPR-based gene editing techniques (see Fig. II.3, 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry), which provide a rapid and relatively inexpensive method to find, cut, and replace genes that may be involved in disease.

- Clinical trials are underway to cure a variety of genetic diseases by CRISPR editing. When in the future such editing is deemed sufficiently safe to use on cells involved in reproduction, it may become possible to eliminate hereditary diseases from entire lines of descendants.

- Gene drives provide a managed-evolution method for forcing edited gene changes to propagate through an entire population over several generations. They are being applied, for example, to eliminate disease-carrying mosquitoes.

- Genome-wide association studies have helped to identify specific genes associated with traits common to a large cohort of individuals but not to a control group. Such results are being used, for example, in forensic DNA phenotyping, where small DNA samples from a crime scene can be used to reconstruct some physical features of criminals in cold police cases.

- Ancient DNA from remains of extinct species is being sequenced with increasing accuracy, fueling attempts to use CRISPR editing to revive extinct species.

Here are some open challenges for genomic research:

- Expand the association of specific genes or groups of genes with specific phenotypic characteristics and specific disease susceptibility.

- Understand in more detail the effects of the large portions of the genome that do not code for protein generation.

- Understand in more detail how environment can influence which genes get expressed.

- Develop a framework to guide how gene editing can be ethically used, discouraging “designer babies,” “super soldiers,” and “designer bioweapons.”

- Can DNA replace more conventional methods of data storage in information technology?

The medical revolution has dramatically advanced the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of diseases and the understanding of human brain functioning. Here are some of the prominent milestones:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), adapted from a technique developed in basic nuclear physics research in the 1930s, has transformed medical imaging. The first MRI images were taken in 1973 (2003 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) but the resolution has been steadily improved to reveal fine details of brain structure (see Fig. II.4). Functional MRI (fMRI) images detect changes in blood flow to reveal which brain sectors are activated while patients perform specific tasks, for example, illuminating paths of addiction and psychological disorders.

- The use of robotic arms and endoscopes have brought about an era of precision surgery to minimize incisions and damage to healthy organs and tissue in a wide range of procedures.

- Establishment of the connection between heart disease and cholesterol and research into regulation of cholesterol metabolism (1985 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) has led to development of cholesterol-controlling drugs, which have helped to reduce the heart disease death rate by a factor of three from 1969 to 2015, although heart disease remains the number one cause of death in the U.S. The development of other targeted drugs are addressing other chronic diseases.

- Discovery of the viruses that cause AIDS (HIV) and cervical cancer (HPV) (2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) has allowed development of drugs and vaccines to treat and prevent these diseases.

- Understanding of the genetic mechanism for constructing antibodies in the human immune system (1987 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) has led to the development of immunotherapies to treat cancers by training the immune system to attack tumor cells (2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine).

- The development of mRNA vaccines (2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) to train the immune system to attack specific proteins surrounding invading pathogens helped to temper the COVID-19 pandemic in record time for vaccine development and is now being applied to prevent many other infectious diseases, as well as to treat various cancers.

Of course, medicine has many remaining open challenges. But there is progress on a few of the most important ones:

- Although a failure to date to find a cure for Alzheimer’s disease has been highlighted by Peter Thiel as one of the symptoms of scientific stagnation – not every problem can be solved on a venture capitalist’s timeline – there has been significant recent progress on at least slowing the progression of the disease in its early stages. Two monoclonal antibody treatments – lecanemab and donanemab – have recently received Food and Drug Administration approval after promising clinical trials. Both of these treatments produce antibodies targeted at clumps of beta-amyloid proteins in the brain, which are characteristic of Alzheimer’s. Research on other treatments to at least slow the cognitive decline is ongoing.

- There is strong progress and a great deal of ongoing research on personalized immunotherapy treatment protocols for specific kinds of cancer. These benefit from precision oncology used to determine the genetic makeup and molecular characteristics of tumors in individual patients. Then, personalized vaccines, for example based on mRNA techniques, can be produced to stimulate a patient’s immune system to attack the cancerous cells.

- A generic goal of medical research is slowing the aging process and extending human lifespans. Craig Venter, who sequenced the first human genome in the year 2000, has launched the company Human Longevity, Inc. to develop precision, personalized, genomic medical care. Clinical trials are underway on several drugs intended to slow the aging process in humans.

There is an ongoing reproductive revolution providing methods to assist human procreation and to monitor embryonic and fetal progress. Here are some of the milestones:

- In vitro fertilization (IVF) (2010 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) was first introduced in 1978 to aid infertile couples by fertilizing egg cells donated by the female with sperm cells from the male in a laboratory setting. Successful embryos resulting from the fertilization can then be implanted in the woman’s uterus to begin a normal pregnancy.

- Pre-implantation genetic testing (PGT) allows embryos produced by IVF to be studied for genetic abnormalities prior to implantation to improve the chances of a healthy pregnancy and infant. It is also being applied by some couples to choose among several IVF embryos the one likely to develop the most desirable features.

- Time-lapse embryo imaging uses specialized cameras inside incubators to monitor the progress of IVF embryo formation before implantation in the woman’s uterus.

- In vitro gametogenesis (IVG) (see Fig. II.5) is intended to provide a further reproductive aid to couples who have difficulty producing eggs and/or sperm. These gamete cells can, in principle, be produced in the laboratory by a technique that reprograms mature somatic cells taken from an individual to become induced pluripotent stem cells (2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine), which can then develop into the needed gametes. To date, IVG has only been accomplished in rodents but research is ongoing to develop the technique for humans.

- Research on the maternal environment impacts on fetal development has illuminated conditions that can lead to abnormalities in fetal brains and atypical sexual differentiation of the brain that may later lead to gender dysphoria.

A possibly profound open question in reproductive science is whether it is possible to develop fetuses outside the womb. Artificial wombs are under development to allow extremely premature infants further weeks to develop in a laboratory or hospital environment. Colossal Biosciences, a company dedicated to the revival of extinct species, is currently researching artificial wombs for use in reviving species such as Steller’s sea cows, which have no relevant existing species to provide surrogate mothers. It would have profound impact on the future of homo sapiens, currently suffering from reduced fertility, if human fetuses could gestate fully and successfully outside a woman’s uterus. On the other hand, it would also bring us closer to the baby production technology envisioned in Brave New World.

The electronics revolution has transformed industry and put significant computing power in the hands and pockets of billions of people. Here are some of the milestones:

- The invention and commercialization of rechargeable lithium-ion batteries (2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry) has had an enormous impact on technology, enabling portable consumer electronics, laptop computers, cellular phones, and electric cars.

- The introduction of metal-oxide-semiconductor (MOS) integrated circuits in the late 1950s (2000 Nobel Prize in Physics) led to the first commercial microprocessors in the early 1970s. The years since have seen a million-fold increase in the number of transistors per unit area as transistor size has been reduced to about 10 nanometers, doubling microprocessor power roughly every two years, in accordance with the empirical Moore’s Law. Modern electronics use customized chips called ASICs (application-specific integrated circuits).

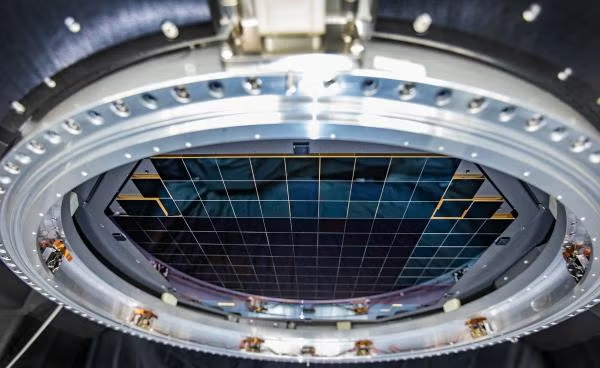

- The development of charge-coupled devices (CCDs, 2009 Nobel Prize in Physics), chips sensitive to light, has been crucial to the rise of digital cameras and the most powerful ground- and space-based telescopes. The newly commissioned Vera Rubin telescope has a 3.2 gigapixel CCD focal plane (see Fig. II.6).

- Microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) – tiny mechanical devices driven by electricity and incorporated within electronic chips – were developed in the late 1980s and are used in digital light processing projectors, inkjet printers, gyroscopes, and airbag deployment in vehicles.

- The miniaturization of microprocessors has fueled the personal computer revolution, culminating in ubiquitous smart phones that today have as much processing power as the most powerful supercomputers near the end of the 20th century.

Current frontiers in electronics development include the following pursuits:

- 3D integrated circuits to pack more processing power into available spaces.

- Reducing the power usage of integrated circuits.

- Transferring data by light rather than electrical signals for higher data transfer speeds at reduced power.

- Incorporating qubits to enable high-performance quantum computing (see below).

- Flexible and wearable electronics for smart clothing.

- Integrated circuit design aided by artificial intelligence.

The computational revolution, which has dramatically transformed access to information, is the one most familiar to lay people. Some of its milestones are well known:

- Development of the internet, which began as a U.S. Department of Defense project in the late 1960s, was rapidly advanced by invention of the World Wide Web around 1990 (2016 ACM Turing Award, often called the Nobel Prize for Computing), to address the needs of enormous international collaborations of physicists and engineers preparing for work on massive detectors and data-rich experiments at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Geneva.

- Internet search engines and encyclopedias have revolutionized the search for information on a very wide range of topics.

- Social media have powered interactions of people around the world.

- The development of deep machine learning (2024 Nobel Prize in Physics) has paved the way for artificial intelligence by allowing programs trained on massive data sets to learn how to determine the optimal paths to extract information ranging from rare physical event signals buried in particle physics data to language usage.

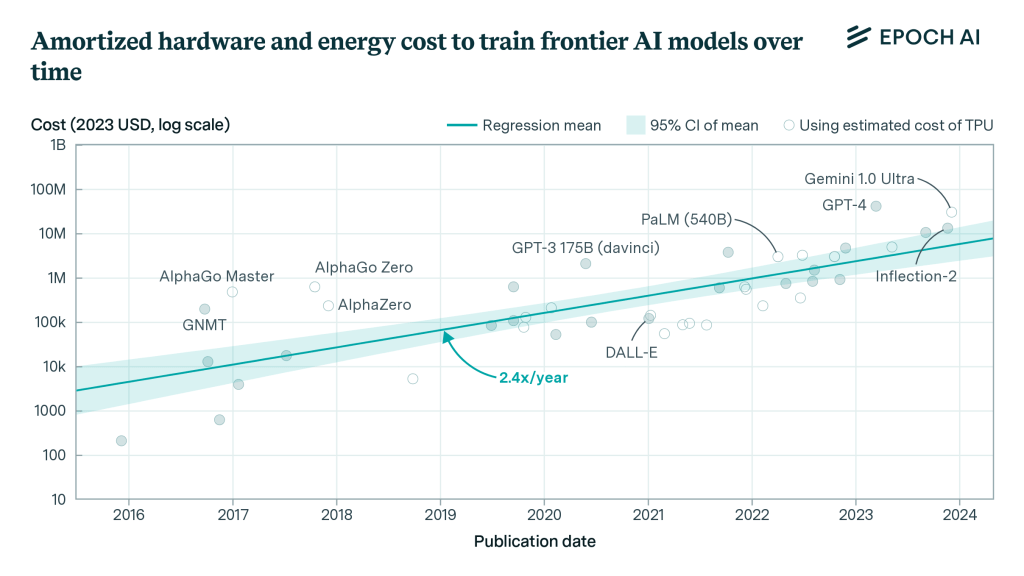

- The ongoing development of artificial intelligence (AI) has allowed applications from game-playing to self-driving cars to facial recognition to chatbots and communicating robots. Generative AI capable of generating text, images, audio, videos, music, and so forth is reshaping workplaces, but at the expense of rapidly increasing demands on electrical energy and cooling water (see Fig. II.7).

- Quantum computing is on the verge of transforming computation by replacing bits with qubits. Whereas a conventional bit can take on a value of either 0 or 1, a qubit can exist in a quantum superposition of 0 and 1, allowing a much wider array of possible results. Manipulations of qubits can use quantum interference effects to speed a wide range of calculations dramatically.

Near-term goals for computation include the following:

- Finalizing the development of artificial general intelligence (AGI), to create machines that can reason, learn, and problem-solve as well as highly competent humans, and perform a wide range of tasks much faster than humans can. But note the following caveats/goals.

- The increasing cost and energy demands of AI illustrated in Fig. II.7 are not sustainable. The development of AI systems that are more energy-efficient is a critical task. Another essential goal is to create AI systems that are capable of distinguishing truth from fiction and lies by looking for inconsistencies with well-established knowledge. Elon Musk has recently given the world an object lesson in the corruptibility of AI when it is trained on the worst of human misinformation and prejudices. The programs are trained on information provided by humans and thus cannot currently be more devoted to truth than are humans. Without improved ability to detect bullshit, AI disinformation systems will outweigh any good provided by AGI.

- The largest current quantum computers comprises a little more than 1,000 qubits. Plans are underway to create one-million-qubit machines, which would vastly increase the capabilities of quantum computers. A 1-million qubit computer could revolutionize the design of new drugs or therapies based on more accurate simulations of molecular interactions, as well as of new materials. It could dramatically advance the optimization of complex systems.

And finally, the last half-century has seen an energy revolution which will take humans beyond the fossil fuel era. Here are some milestones:

- Climate monitoring and modeling of increasing sophistication (2021 Nobel Prize in Physics) has made it clear that the burning of fossil fuels by humans is the predominant cause of ongoing global warming. The effects of the warming are already being felt, for example, in the increasing frequency of severe storms, heat waves, droughts, floods, and forest fires, in the bleaching and dying of coral reefs worldwide, and in the accelerating melting of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets. If the warming continues throughout this century, climate tipping points will be passed, leading to much more severe outcomes.

- Technological developments of wind turbines, photovoltaic solar panels, and concentrating solar plants have fueled rapid growth during this century in the share of worldwide electricity generation that is attributable to renewable energy sources (see Fig. II.8). Ongoing research to improve the efficiency of both solar and wind energy production will help to fuel a continuing increase in the renewable share over the coming decades, as fossil fuel production is phased out.

- The development of small modular fission reactors and of molten salt reactors has created the opportunity to replace aging large fission reactors as they are retired, so that nuclear fission power can maintain its share of global electricity production.

- Recent breakthroughs in energy production from nuclear fusion, together with the multi-country collaboration on the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), have renewed the promise of fusion to provide clean, carbon-free nuclear power during the second half of the 21st century, without the problems of thermal runaway and extensive radioactive waste that plague fission reactors. For Peter Thiel, who claims that humans have become too risk-averse to pursue dramatic advances, the $22 billion dollars invested by multiple countries into ITER represents a major risk to advance worldwide electricity production while avoiding the worst impacts of global warming.

- The discovery of high-temperature superconducting materials (1987 Nobel Prize in Physics) is now allowing construction of compact, very high field strength electromagnets, as needed for future commercial fusion reactors.

Arguments could certainly be made to include additional revolutions, for example, in materials science. Whether one agrees or not that the seven areas of major advances outlined above can be labeled as scientific revolutions, they certainly contradict claims that science and technology have been stagnating since the late 20th century. These advances will continue to provide a strong return on investments in scientific research.

— Continued in Part II —