September 25, 2024

I. introduction

It has been three decades since the first introduction of genetically engineered (GE) crops to food markets around the world. And yet consumers worldwide remain largely unconvinced of their value or safety. The ‘GMO’ label generically attached to these foods has become a signifier of risk for the public. In this post we will discuss the science of genetically engineering plants, the reasons for public skepticism, scientific studies and reviews of GMO food safety, and a number of specific marketed products.

But first we offer a comment on terminology. Foods that contains products of genetically engineered crops have traditionally been labeled as ‘GMO,’ but this is a slightly misleading label and that has contributed to some of the controversy surrounding these products. First of all, GMO is actually a much broader term, applying to any organism modified by one or another technique of modern genetic engineering. For example, it could be applied to the attempts to revive extinct animal species that we have described in a previous post or the attempts to engineer sterility into malaria-bearing mosquitoes. Secondly, the term does not distinguish sufficiently from natural processes. Evolution by natural selection leads to species that are genetically modified with respect to other species. Conventional crop breeding techniques seek to produce genetically modified properties. We prefer the term ‘genetically engineered’ crops to signify the explicit human intervention to introduce DNA properties chosen by human {as opposed to natural) selection, even if these would be extremely unlikely to ever occur naturally. Because public attitudes toward the foods are based on the labels ‘GMO’ or ‘non-GMO,’ we will continue to refer to GMO foods, but when we discuss the science and the crops we will use the GE terminology.

While some individual farmers and food companies have been happy to label their products as ‘non-GMO,’ the U.S. government has long been reluctant to go against the wishes of genetically engineered seed producers and require them to label food products derived from their seeds. So consumers are not only skeptical about the value of genetically engineered foods, but also mostly in the dark about whether they are consuming such products or not. As illustrated in Fig. I.1, a surprisingly large percentage of some fruits and vegetables presently sold in the U.S., prominently including corn, soy beans, sugar beets, and canola oil, are indeed unlabeled GMO foods.

The U.S. government reluctance about labeling was finally modified when Congress passed the 2016 National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard. But that standard seems designed only to increase the confusion of consumers. It requires producers by January 1, 2022 to label their genetically modified food products in one of three ways, none of which use the letters ‘GMO’: the package may include the words ‘bioengineered food’ or ‘contains a bioengineered food ingredient’; or it may include one of two logos for bioengineering approved by the U.S. Department of Agriculture; or it may simply include a QR code or a phone number that consumers can scan or call to find out more information. And enforcement of the law can take place only in response to complaints.

Consumers are also unsure of the benefits to them of genetically engineered crops. In a foreword to Sheldon Krimsky’s book GMOs Decoded, Marion Nestle states that: “The industry also promised that food biotechnology would feed the world and create new foods that would solve problems for the developing world, such as those able to withstand poor soil conditions, excessive heat, and limited water. But instead, the industry concentrated on far more profitable insect- and herbicide-resistant first world crops…” In fact, the bioengineered seed industry markets to farmers, and mostly to large industrial farms, not to consumers directly. Nearly all commercially available genetically modified foods have been engineered to improve crop resistance to herbicides, insects, and diseases.

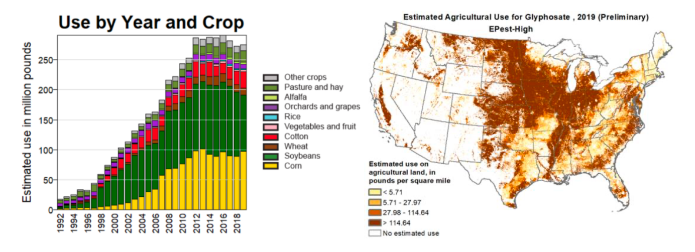

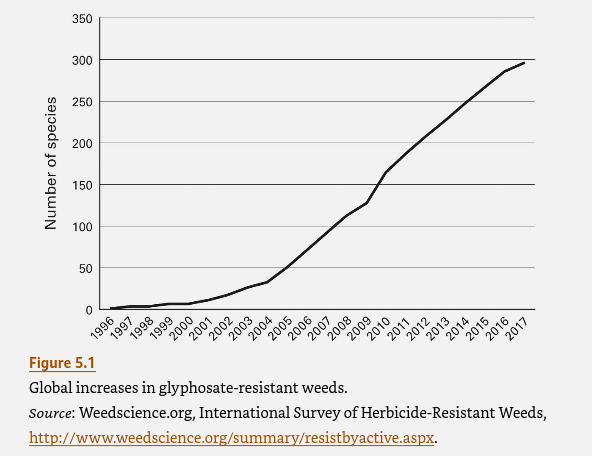

The profitability of that approach for the seed manufacturers is well illustrated by Monsanto’s marketing of “Roundup Ready” crops. Monsanto developed its weed killer Roundup in the 1970s on the basis of its patent on the herbicidal properties of the chemical glyphosate. Roundup sales were initially okay but limited by the fact that its application also destroyed many crops. When techniques for genetic engineering were first discovered, Monsanto seized the opportunity to send sales skyrocketing. Monsanto and other chemical giants bought up seed-producing companies starting in the 1980s. Monsanto then introduced its first genetically engineered glyphosate-tolerant soybean seeds in 1996 and followed up for other crops shortly thereafter. The company not only sold lots of seeds but also saw the use of glyphosate — to kill weeds but not marketable crops — grow very rapidly, as illustrated in Fig. I.2. As various weed varieties then began to evolve their own glyphosate resistance (see Fig. I.3), farmers sprayed more and more glyphosate and sales continued to grow, before leveling off in about 2012. Despite the fact that Monsanto was earning multiple billions of dollars annually from Roundup sales, the company was sold to the German company Bayer in 2018, as Monsanto faced multiple lawsuits with billion-dollar damage assessments from Roundup’s role in causing cancer.

The genetically engineered seed manufacturers claim that their modifications are not qualitatively different from conventional breeding approaches long used in agriculture. They have tried to assure consumers that the engineered modifications carry no health risk. Many scientific studies have been carried out to assess safety, looking for indications that the genetic changes might cause effects that are either toxic, carcinogenic, or allergenic, and have produced both negative and positive results. Nonetheless, major reviews of all those studies have concluded that there is not yet any convincing evidence of pervasive health hazards.

A prominent study in this regard was provided by the U.S. National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) in 2016 in their exhaustive report Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects. The NASEM report cautions that “the technologies, traits, and contexts of deployment of specific GE crop varieties are so diverse that generalizations about GE crops as a single defined entity are not possible.” They offer various recommendations about ways to improve testing of GE crops. But in the meantime they conclude: “The Committee could not find persuasive evidence of adverse health effects directly attributable to consumption of GE foods.” A similar conclusion was reached in 2019 by an Advisory Panel to the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare.

The tension between findings of distinguished scientific panels and widespread public skepticism has created a conundrum for governments deciding whether to regulate GMO foods and, if so, how. Different countries have made widely divergent choices. For example, Russia has completely banned the cultivation and importation of GE crops. As of 2015 cultivation was banned in 38 countries, prominently including France and Germany and most of the European Union, although Spain and Portugal have approved cultivation of one specific GE variety of insect-resistant corn. In contrast, the U.S., China and Australia are major suppliers of GE crops, along with 26 other countries.

Although most EU countries ban cultivation, Europe is one of the world’s major consumers of GE crops, especially biotech corn and soy for livestock feed. But the sale of GMO foods is heavily regulated in the EU. All GMO foods, in addition to crops generated by mutations induced by radiation (a technique normally included among “traditional” breeding mechanisms), are subjected to extensive, case-by-case evaluation by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). The EFSA mandates certain safety tests and recommends others for each food product, requires accurate labeling and traceability of GMO products, and considers whether consumers have adequate “freedom of choice” in food selection. If the EFSA decides that the GMO product is “substantially equivalent” (even though not chemically identical) to a non-GMO counterpart, they recommend approval for sales in the EU. Furthermore, “even after authorization, individual EU member states can ban individual varieties under a ‘safeguard clause’ if there are ‘justifiable reasons’ that the variety might cause harm to humans or the environment.”

In marked contrast to the EU, the U.S. maintains an “innocent until proven guilty” approach toward GMO foods. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has adopted a policy that genetically engineered foods are “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS) and “substantially equivalent” to analogous foods developed by traditional breeding techniques. They see genetic engineering as not qualitatively distinct from traditional breeding methods. They therefore leave to the food manufacturers themselves the responsibility for carrying out risk assessment of their products and fairly reporting the results of their tests. The Department of Agriculture had been reluctant to impose any requirement on labeling GMO products until the adoption of the confusing Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard discussed earlier.

We attempt in this post to summarize the current understanding of the various technological approaches to genetic engineering of crops and to more traditional breeding methods, and to assess whether there are qualitative differences between the two. We discuss surveys and reasons for public skepticism about GE crops and the absence to date of compelling safety results to quell that skepticism. We discuss specific crops engineered to advance agricultural productivity and assess whether such advances have indeed been found to outlive the evolutionary adaptation of weeds, insects, and bacteria to resist the engineered DNA changes in the crops. In Section V of this post, we discuss the 2016 NASEM report on GE crops, its conclusions, cautions, and possible shortcomings. In Section VI, we discuss the failure to date to commercialize many GE crops designed instead to improve nutritional value for consumers, with specific focus on the product Golden Rice. In all of these descriptions we rely heavily on Krimsky’s well-balanced accounts in GMOs Decoded, along with a variety of other sources. And we offer our own opinions about the essential need for clear and accurate labeling of GMO products to facilitate informed consumer choices and meaningful long-term epidemiological research to evaluate human health impacts.

II. Techniques of conventional breeding vs. genetic engineering

Conventional breeding of plants, whether for new flower varieties or new crops, has been proceeding for at least two centuries. Hybrid species are produced by cross-pollination of two related species, often via human intervention in the breeding process. When the two species of interest are not naturally reproductively compatible, human intervention becomes essential to create hybrids. Methods using electrical currents, wire brushes, or heat treatments have succeeded in inducing “reluctant stigmas to be fertilized by foreign pollen.” The hybrid embryos created in such processes have to be developed in a laboratory culture with appropriate nutrient solutions, so the technique is known as embryo rescue.

Conventional breeding methods are usually classified to include at least one technique of purposely modifying a plant’s DNA, known as mutagenesis. In this approach one exposes a plant to radiation or chemicals to cause random DNA mutations, which might occasionally, though unpredictably, lead to improvements in the plant’s appearance or robustness. The technique was highlighted in the title of a 1970s play, The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds. Mutagenesis is basically a process to speed up natural processes of mutation and evolution, but without any human control over the outcome. But because it alters a plant’s DNA it has been central to claims that modern genetic engineering techniques are merely part of a continuous spectrum of plant breeding methods. We noted earlier that in European Union regulations crops generated by mutagenesis are lumped together with GMO foods to be assessed for approval on a case-by-case basis by the European Food Safety Authority.

Recombinant DNA:

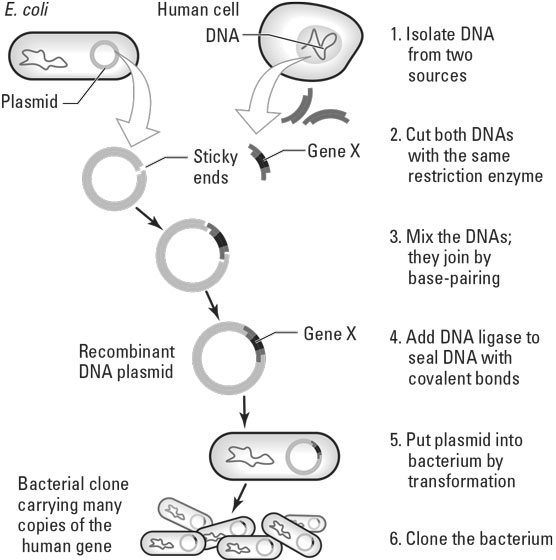

We have dealt extensively in previous posts (see here and here) with the gene-editing procedure known as CRISPR/Cas9, which was established in 2012. CRISPR is being applied today to create GE crops, as we will describe further below, but the vast majority of marketed GMO foods were generated instead by the older technique of recombinant DNA. As applied in plant breeding, recombinant DNA is a method for transplanting a specific gene or genes extracted from the DNA of organisms of one species into the germ cell (i.e., a cell involved in reproduction) DNA of the species to be modified. The resulting modified plants are called transgenic. Basic steps in the procedure are illustrated schematically in Fig. II.1.

Genes are DNA sections that encode the production of proteins with specific functions. The first step in creating a GE crop by recombinant DNA is to identify specific genes in some donor species that produce proteins that will generate the desired characteristic, such as glyphosate tolerance, when inserted into the DNA of the targeted host species. DNA is extracted from the chromosomes of the donor organism and many copies are made. Cleavage enzymes, known as endonucleases, are used to cut out the genes of interest from many of those copies. The extracted genes comprise mostly double-stranded helical sequences of paired nucleotides (from the four chemical categories labeled A, C, G, or T) that form the building blocks of DNA, but they contain “sticky ends” of single strands that will aid their adhesion into a carrier for transport and penetration into host cells.

The carriers generally used are plasmids, which are small, circular double-stranded DNA molecules commonly found, physically separated from the chromosomal DNA, within bacterial cells (such as the E. coli in Fig. II.1), where they can replicate independently of the chromosomes. The bacteria usually used to supply plasmids for producing transgenic crops is known as Agrobacterium tumefaciens or A. tumefaciens, a soil-dwelling bacterium that infects some plants.Endonucleases are also used to cut out a section of each plasmid, into which the extracted donor genes will hopefully settle. Plasmids that don’t successfully recombine with donor genes repair their cuts by simply joining the cleaved ends together. All of the plasmids are then reinjected into A. tumefaciens cells and the bacteria are allowed to reproduce by cloning in a culture.

Not all cleaved plasmids and donor genes will successfully recombine, so the donor genes are accompanied also by marker genes, which allow the breeder to detect which plasmids have accepted the transgenes. For example, the markers may add resistance to a given antibiotic so that when the bacterial sample is exposed to that antibiotic only the cells with recombined DNA survive. The transgenes are also accompanied by a termination sequence comprising three paired nucleotides that signal the end of the coding section of the transgene. In addition, they are accompanied by a promoter DNA sequence that will facilitate the expression of the transgene once it is in its new environment within cells of the host organism.

The surviving bacteria are then used to penetrate cells of the host plant in a tissue culture, where they inject the transgenes into the host cell chromosomes. The modified cells are allowed to reproduce in the culture until a transgenic plant seedling can be carefully grown under laboratory conditions. When the seedling is sufficiently robust it can be planted and cultivated in a field. The health and characteristics of the transgenic plants can be monitored to see if the desired traits have been successfully transferred and their yields are adequate, and their safety can be assessed by chemical analysis and/or animal studies. It often requires many attempts at DNA recombination to produce a single successful transgenic plant. Successful transgenic plants can then generate seeds for sale to farmers.

Recombinant DNA has been used to introduce glyphosate tolerance, insect and disease resistance into transgenic plants. It has also been used to produce a variety of rice (so-called Golden Rice) and other vegetables that express enzymes responsible for the synthesis of beta-carotene, which holds the promise of reducing the incidence of vitamin A deficiency in many countries. All of these applications will be discussed in more detail in later sections. But recombinant DNA is a hit-or-miss process. There is little control over where within a host chromosome the transgene will be inserted and how its expression will interact with those of its neighboring genes or neighboring non-coding DNA in the new environment. If the transgene is expressed, it is not a priori clear that the protein it produces will generate only the desired trait change and no deleterious effects, either to the plant itself or to an eventual consumer of the plant or its products.

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing:

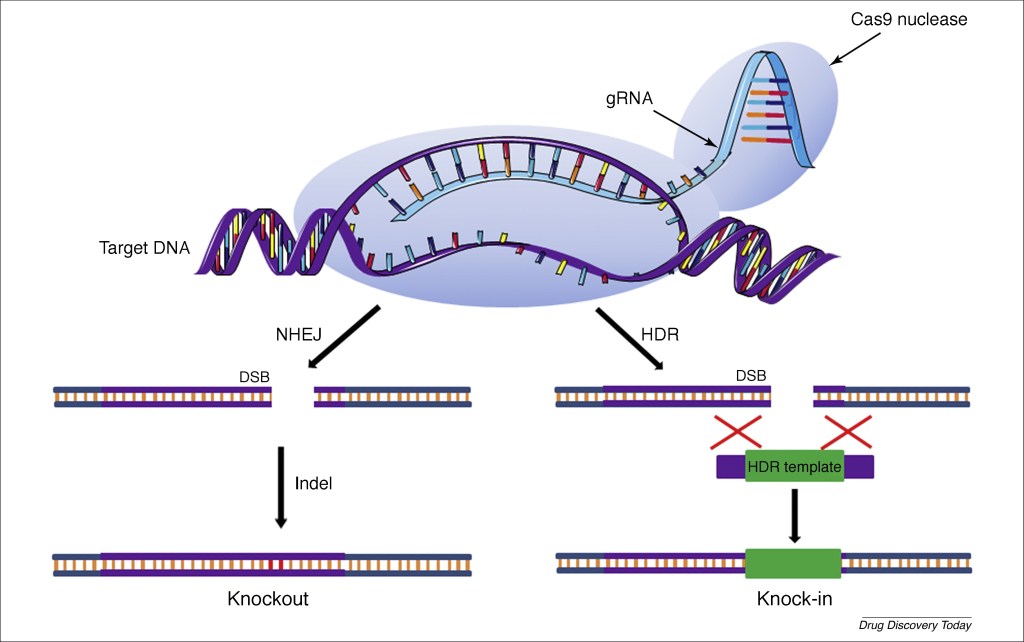

Plant breeders are thus eager to exploit the more precise elements of more modern gene-editing techniques, of which CRISPR/Cas9 is now the method of choice. It provides the biomolecular equivalent of find, cut and paste word-editing procedures to allow a payload gene to be edited directly into a desired location in targeted DNA. As illustrated in Fig. II.2, a guide RNA molecule is engineered to attach itself to a single strand of the targeted DNA section at a specific location, so that the associated Cas9 enzyme can then cut the double-stranded DNA at both ends of the targeted section. The payload gene in the CRISPR complex can then be edited in to fill the resulting gap by a natural DNA self-repair mechanism. The payload gene can be extracted from another member of the same species (when it contains an alternative, and more desirable, variant of the gene in question), from an organism in a different species, or can even be synthesized in the laboratory.

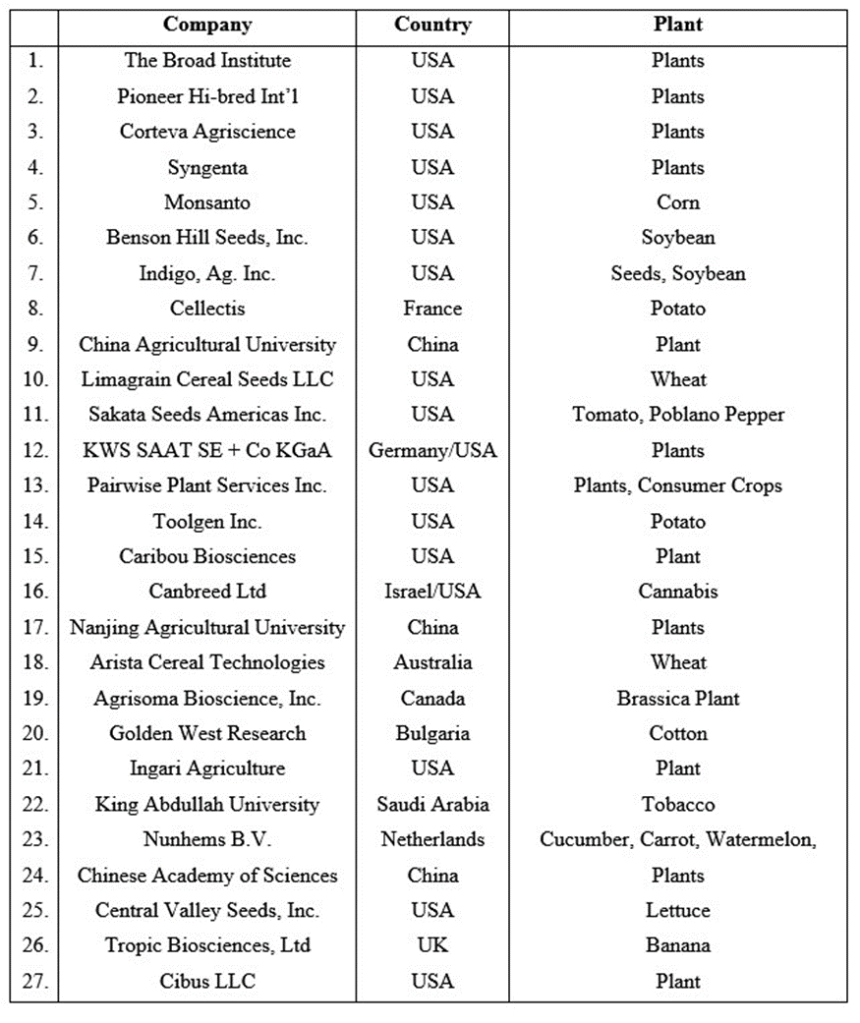

Worldwide patent applications to use CRISPR editing to improve agricultural crops began in about 2014 and have increased exponentially since. Some of the patent holders and crops covered are indicated in Fig. II.3. The patent filings cover “all plant types, including rice, tomato, maize, soybean, tobacco, alfalfa, wheat, rapeseed (canola), cotton, and cannabis.” Some of the patent applications address traits to meet consumer demand, such as “gluten free, reduction in browning, reduction in allergen levels, improved fruit color, flavor, and shelf life.” Others address traits that benefit farmers, such as resistance to viruses, bacteria, and fungi, increased tolerance to temperature variations and drought, and improved crop yield.

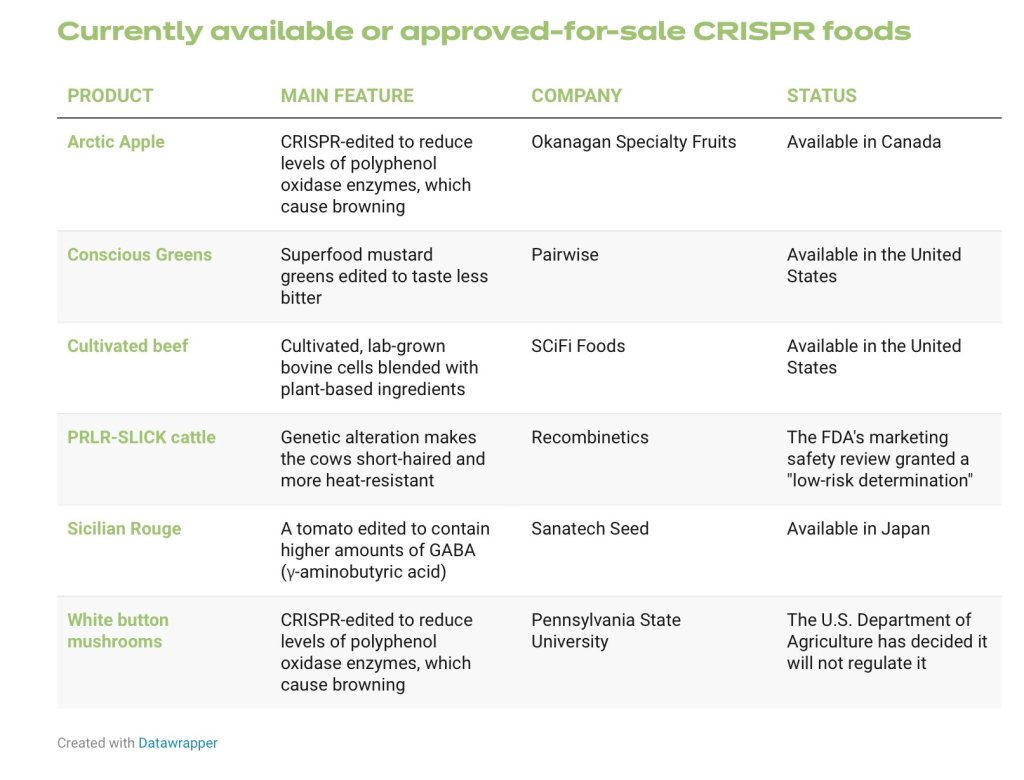

As of July, 2023 the CRISPR-edited foods that have already hit the market or been approved for commercial sale are summarized in Fig. II.4. The first of these foods to reach commercial markets was the Sicilian Rouge High-GABA Tomato, marketed in Japan beginning in 2021. GABA, or gamma-aminobutyric acid, is a neurotransmitter that appears naturally in the human brain, where it helps to regulate the brain’s activity between neurostimulation and calmness. “Dietary GABA has been linked to reduced anxiety, stress relief, insomnia relief, lower blood pressure, and improved cognition.” Tomatoes are naturally rich in GABA, so the researchers for Sanatech Seed “did not add any exogenous gene to the tomatoes’ genome but just edited the tomato’s own GABA synthase enzyme to cause an increased conversion of glutamate. Confident that the company’s claims were verified, Japanese regulators decided that the fruit should not be labeled as a ‘genetically modified’ crop.”

CRISPR gene editing is certainly more precise and controllable than recombinant DNA modifications or mutagenesis. And the early applications seem more focused on improving food quality for consumers than most commercial applications of the recombinant DNA techniques. But CRISPR/Cas9 editing is not without flaws. It occasionally makes DNA cuts and unplanned changes in non-targeted sections of DNA. Some of these off-target collateral damages might conceivably be toxic or allergenic. While there is ongoing research aimed at reducing the occurrence of off-target effects, such collateral damages could undermine the improvements aimed for in CRISPR-edited crops. Hence, despite wishes of the industry to avoid regulation altogether, it seems prudent to require safety approvals for CRISPR-edited crops that are similar, but not necessarily identical, to the procedures required for more conventional GMO foods. Currently, the U.S. Department of Agriculture imposes minimal restrictions on CRISPR-edited crops that do not introduce foreign DNA or pesticidal properties to the engineered crops. But DNA sequencing should be carried out on CRISPR-edited plants at least to check that there are not off-target modifications.

Is genetic engineering qualitatively different from conventional breeding?:

Much of the debate concerning genetically engineered crops has centered around the question of their similarity to foods obtained by conventional breeding methods such as hybridization. Conventional methods may mix genetic properties of two different plant species, but the two species have to be relatively closely related for cross-breeding to occur, even with human help in embryo rescue techniques. Recombinant DNA, on the other hand, is qualitatively different since it can bring in genes from species that are far removed in a phylogenetic tree from the plant being modified, and hence, make changes that could never occur naturally. For example, the glyphosate-tolerant crops marketed by Monsanto are based on a transgene derived from microorganisms, which produces an enzyme relevant to plant growth that is glyphosate-insensitive.

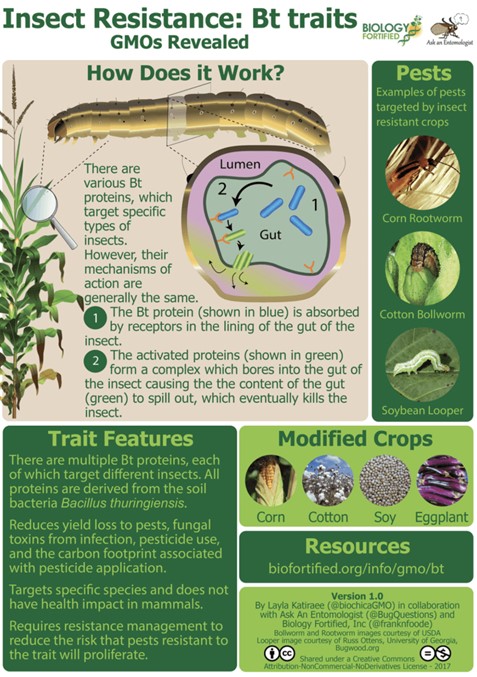

Insecticides have been engineered into the germ cells of many GE plant species via transgenes that encode crystalline proteins (called Cry proteins) produced by the soil-based bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis (normally abbreviated by Bt), when it forms a spore. Different Cry proteins are toxic to different types of insect. One such insect-resistant GMO product, StarLink corn (see Section IV) modified with the Bt protein Cry9c, was approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (which regulates pesticides) for use in animal feed, but was rejected for human consumption in the year 2000 on the basis of concerns that those proteins toxic to corn borers might cause allergenic effects in humans. There should always be concerns about potentially harmful effects of the transport of genes that could hardly end up in crops by natural means. Transgenic GMOs require testing to demonstrate their safety.

When CRISPR is used to edit in different variants of a gene already present in a plant species, or transgenes from closely related species, it is more similar to conventional breeding, except for concerns about off-target DNA alterations. But CRISPR can, in principle, also be used to edit in transgenes from distant species or even synthetic genes. In such cases, it is also qualitatively different from conventional breeding methods. In any case, as emphasized in the 2016 NASEM GE crop report, there is as yet no standardized quantitative metric for determining that a GE crop is “substantially equivalent” to one generated naturally or by conventional breeding techniques, even though that qualitative criterion is invoked in decisions by numerous food regulation agencies worldwide.

III. much of the public skepticism is rational

Before going into more detail about specific GMO foods, it pays to assess public perceptions. Worldwide public attitudes toward GMO foods were surveyed in 2019-20 by the Pew Research Center. The basic results of the survey are displayed in Figs. III.1 and III.2. While attitudes differ considerably among different countries, perhaps the most important takeaway from the survey is that in none of the countries is there more than one-third of the public that considers GMO foods to be generally safe for human consumption. Up to one half of the population in each country feels they don’t have sufficient information to judge. In the U.S. 27% of people consider GMO foods generally safe, 33% don’t feel they have enough information to judge, and 38% consider the foods unsafe. The even larger fractions of Europeans who consider GMO foods unsafe helps to explain some of the significant regulatory differences between the U.S. and the E.U. Figure III.2 demonstrates that women, who are typically more involved in food preparation, are considerably more skeptical of GMO food safety than men in all countries surveyed.

Much of the widespread skepticism appears to us to be rational. People like to know what is in the foods they eat and they seldom understand in any detail what genetic engineering has done to the crops. The technology is still relatively new and it seems too early to know whether there might be long-term negative health impacts. It took a half-century of heavy cigarette smoking across the globe before epidemiological studies had enough precision to establish a clear link between smoking and lung cancer. Industry assurances of product safety have frankly been highly devalued by the history we have reviewed in other posts on this site of corporations’ repeated efforts to hide their own internal findings of toxicity or other adverse health effects from the public. Indeed, we have reviewed in detail Monsanto’s efforts to use the toxic product defense industry and to fund or even ghost-write research papers refuting a finding by the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer that glyphosate is “a probable human carcinogen.” In the case of Roundup-ready GE crops, safety is a concern not only for consumers but also for farm workers, who have the greatest exposure to glyphosate.

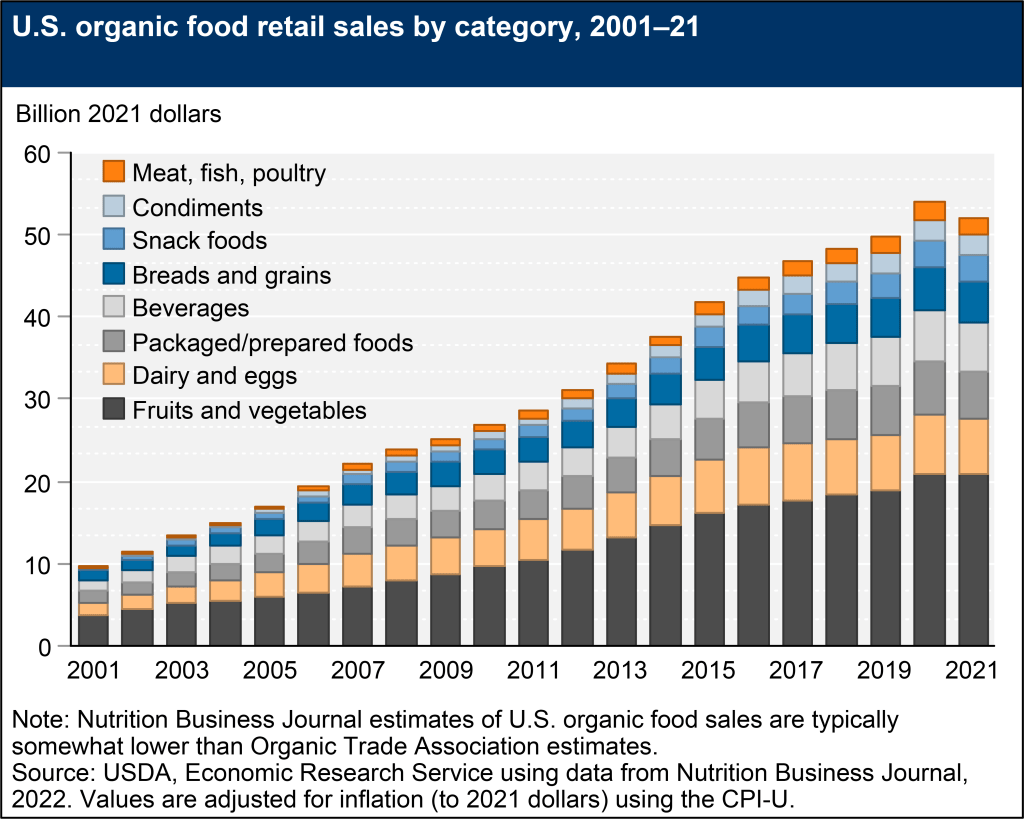

Furthermore, the GMO food industry has developed during a period of growing preferences for natural, organic (which are required to be non-GMO), and often locally sourced farm products. For example, Fig. III.3 illustrates the rapid growth in organic food sales in the U.S. during this century. The Pew survey results in Fig. III.4 show that organic food preferences are strongest among the young, and that among those who care some or a great deal about GMO foods 2/3 to 4/5 believe that organic foods are better for health. Organic farms are typically small and individually owned. The GE seed manufacturers instead sell predominantly to large, industrial farms.

The strong resistance GE seed manufacturers have put up to labeling GMO products only adds to public skepticism and uncertainty about what they are eating. This is especially true in the U.S., where the Food and Drug Administration relies on the GMO food manufacturers to do their own safety testing. The manufacturers are generally more interested in the robustness and yield of the crops than in the potential for long-term health impacts on consumers or farm workers. Their opposition to labeling in the U.S. has been based on a claim that labeling would reduce sales and therefore raise prices. In fact, surveys have found that consumers in both the U.S. and the E.U. (where labeling is mandatory) are only willing to purchase GMO foods at discounted prices compared to non-GMO alternatives, even when the engineering introduces a physical improvement visible to consumers, such as apples resistant to browning after being sliced. So, raising prices on labeled GMO foods would likely suppress sales even further than labeling alone.

To date, there are inadequate safety standards. The generic worldwide criterion used to judge GMO food safety is assessment whether the GMO food is “substantially equivalent” to the non-GMO counterpart. However, the 2016 National Academies report acknowledges that “No simple definition of substantial equivalence is found in the regulatory literature on GE foods.” The report expresses doubts about the methodology and validity of tests that have evaluated health impacts of GMO foods on animals, and such tests are not required by the U.S. FDA in any case. In tests comparing chemical properties of GMO and non-GMO foods, the NASEM study questions both the statistical and biological relevance of many tests carried out to date. The bottom line of the report, to be described in more detail in Section V, is that we haven’t seen any convincing evidence of consumer health impacts yet. Much of the public wants to see continued testing and a clearer explanation of how GMO foods benefit consumers.

Not all of the public skepticism is based on individual, rational doubts about safety. A good deal of it is promoted by organizations that oppose nearly all corporations and globalization and feel no need to see more data. These organizations fear domination of world food markets by a few large GE seed corporations — Big Seed to join ranks with Big Pharma, Big Tobacco, and Big Oil. Greenpeace, for example, has worked to promote much of the skepticism of GMO foods in Europe. They have even fought, to the consternation of many scientists, to block the marketing of golden rice, one of the few noble efforts of genetic modification to date, aimed at improving human health, by overcoming vitamin-A deficiency in many countries. Section VI of this post provides a review of the Golden Rice issue. The Institute for Science in Society, a strident critic of GMO foods, declares that “Genetically modified (GM) crops…will not play a substantial role in addressing the challenges of climate change, loss of biodiversity, hunger and poverty.” Perhaps it would be wise instead to see what CRISPR editing can accomplish toward those ends in the near future, before dismissing the possibilities out of hand.

What is clear is that genetic engineering of foods must be regulated by governments. The first required step is mandating clear and accurate labeling of both GMO and non-GMO products worldwide, with unambiguous standards and non-confusing product labels. This will allow consumers to exercise their freedom of choice in deciding what to eat. Over decades, controlled epidemiological studies of health outcomes for comparable groups of consumers who have, and who have not, consumed GMO foods may begin to deliver more meaningful data on safety that can then inform all consumers going forward. It seems unlikely to us that public perceptions will change dramatically from the current widespread skepticism until there are such long-term, large-sample studies of comparable groups.

IV. GMOs to advance agricultural productivity

As we have mentioned, transgenic crops have revolutionized the farm industry. Since their introduction to American farming in the mid-90s, transgenic crops have dominated areas such as corn, soybeans, and cotton. In this section we will review three different purposes for transgenic plants. The first of these is crops that are resistant to certain herbicides. Such crops are sprayed with a specific herbicide – the most dominant is glyphosate which is marketed under the trademark Roundup. Roundup kills a wide variety of weeds, but the crops are resistant to Roundup and thus survive. A second type of transgenic plant is altered to make them resistant to plant pathogens such as bacteria, viruses or fungi. A third type of transgenic plant is modified so that the plant contains proteins that are toxic to a particular insect. When that insect feeds on a transgenic plant, certain ‘Cry’ (crystal endotoxin) proteins are expressed in the gut of the insect. Those proteins kill that insect. The great appeal of these insecticidal plants is that they only kill specific insects. The Cry proteins appear to be benign to other insects and to humans.

A: Roundup Ready Crops

Some of the most widely used transgenic products are called ‘Roundup Ready’ (RR) plants. These were developed by the Monsanto Corporation, which developed and commercialized them. In 2018, Monsanto sold this company to chemical giant Bayer. The first commercialized Roundup Ready crop was soybeans, which were first introduced in the U.S. in 1996. In 1998, Roundup Ready corn was introduced. Since then, Roundup Ready varieties of canola, sugar beets, cotton and alfalfa have been rolled out. Figure IV.1 shows a schematic picture of a Roundup Ready plant together with a normal plant or weed. The Roundup Ready plant has a gene inserted that makes it resistant to glyphosate. When the herbicide Roundup, with the active ingredient glyphosate, is sprayed on a field, normal plants and weeds are killed by Roundup; but the Roundup Ready plant is engineered to survive.

Here is how the gene modification is carried out for soybeans. The bacterium Agrobacterium CP4 possesses a gene that is resistant to glyphosate, specifically the EPSPS gene (5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase for the chemistry lovers among you). A plasmid containingtwo CP4 EPSPS genes and a markergene extracted from E.coli are then injected into one specific variety of soybeans using a device called a ‘gene gun.’

Herbicide-resistant GE plants have become a massive business. Monsanto researchers realized that glyphosate was a herbicide in 1970, and in 1974 they marketed glyphosate under the trade name Roundup. It was also realized that glyphosate was less toxic to animals, compared to other herbicides used in farming. At that time, seed companies produced and sold their own varieties of seeds, while chemical companies produced herbicides. However, after Monsanto discovered that they could use genetic engineering to produce seeds whose plants were resistant to a specific chemical (in this case, glyphosate), chemical companies bought up seed producers and created their own transgenic seeds that were resistant to their own weed killer chemicals.

Figure IV.2 shows a canister containing Roundup. Bayer bought out Monsanto in 2018 for $63 billion, despite the fact that Roundup, the world’s best-selling herbicide, was the target of thousands of lawsuits from people who claimed that it caused their cancers. In June 2020, Bayer agreed to a $10 billion payment to settle claims against Roundup for causing cancer.

In 1974, 800,000 pounds of glyphosate was applied by farmers. But by 2014, 250 million pounds of glyphosate was used in U.S. agriculture. By 2003, Monsanto was the largest producer of genetically engineered seeds on the planet; Monsanto accounted for over 90% of the GE seeds planted globally. By 2018, 93% of U.S. acres devoted to soy beans were using transgenic seeds, while 83% of corn and 82% of cotton was GE plants. The great success of Roundup Ready seeds leads immediately to the vexed question: what are the benefits and drawbacks of using GE seeds? The first issue is whether Roundup Ready products lead to less use of herbicides. For RR cotton and soybeans, for a certain amount of time the net herbicide use decreased. However, as should be obvious, continued use of glyphosate herbicide led to the evolution of Roundup resistance among the weeds. Thus, over time larger and larger amounts of glyphosate were needed to provide the same weed-killing ability. The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture stated that “An overreliance on glyphosate and a reduction in the diversity of weed management practices adopted by crop producers have contributed to the evolution of glyphosate resistance in 14 weed species and biotypes in the United States.” As shown in Fig. I.3, by 2017 there were nearly 300 weed species worldwide that had developed resistance to glyphosate.

One benefit of using RR crops is that the reliance on more toxic herbicides decreases; also, those other herbicides tend to be more toxic to animals. The toxicity is often measured using the LD-50 dose; LD-50 is the dose of a substance, “in milligrams per kilogram of animal body weight, which when administered as a single dose will produce death within 14 days of half of a group of 10 or more laboratory white rats.” The larger the LD-50 dose, the less toxic the substance. On this scale, glyphosate has an LD-50 of 4,900; by comparison the LD-50 dose of alternative herbicide paraquat is 100, 2,4-D is 666, and atrazine is 3,090. On the other hand, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) declared in 2015 that glyphosate is “a probable human carcinogen,” despite furious lobbying and counter-claims by Monsanto.

Another issue is whether the use of GE crops results in decreased costs for farmers. It is argued that farmers will benefit from using Roundup Ready plants, because they will have to spend less time weeding. However, as time goes on, the use of herbicides in RR fields will increase as glyphosate resistance among weeds grows. A 2010 USDA study showed that “Herbicide use on corn by HT (herbicide tolerant) adopters increased from around 1.5 pounds per planted acre in 2001 and 2005 to more than 2.0 pounds per planted acre in 2010, whereas herbicide use by nonadopters did not change much.”

One of the touted advantages of RR crops is that they are claimed to have higher yields than traditional varieties. But a 1999 review of Roundup Ready soybean crops found that they had a 6.7% lower yield than the top conventional soybeans. Monsanto challenged this finding, saying that their later varieties of RR soy produced yields that were 7-11% higher than the earlier variety; however, Monsanto did not publish the actual yields of this new variety.

Reports from the non-profit Union for Concerned Scientists (UCS) give reasoned arguments against the long-term use of genetically engineered herbicide-tolerant plants. The UCS argues that the goal should be sustainable agriculture, i.e. “both highly productive and protective of the natural resources on which future productivity depends.” UCS claims that Roundup Ready crops are not sustainable in the long run, since weeds will evolve to acquire resistance to Roundup. In that case, farmers will either use successively larger amounts of Roundup herbicide, or supplement Roundup with additional more toxic herbicides, or else return to tilling their fields, a practice that has numerous ecological drawbacks. In addition, UCS claims that our nation’s traditional seed supply is slowly but surely becoming contaminated with seeds containing transgenic products. To counter this, UCS argues that the US Dept of Agriculture (USDA) should tighten regulations to minimize mixing of transgenic and traditional seeds. In addition, UCS urges the USDA to create a repository of traditional seeds that are free of pollution by transgenic products.

B. Disease-Resistant Transgenic Crops

Crops are affected by a number of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses and fungi. In the U.S., it is estimated that between 8% and 23% of vegetable crops are lost each year to plant disease. Here we will discuss transgenic methods for conferring resistance to disease using the example of the papaya, a major source of income in Hawaii. In the 1950s, a virus called papaya ringspot virus or PRSV wiped out the papaya industry on the island of Oahu. Papaya growing then moved to the Puna area of Hawaii’s Big Island; however, PRSV emerged there in the 1990s. A method using biotechnology has been developed to induce papaya immunity against PRSV. A transgene is developed that contains fragments of the PRSV genome. The transgene is then connected to a promoter, which is often the cauliflower mosaic virus. This is then introduced into the host cells of the plant using a gene gun. After the transgene has entered the host cells, when the cells are exposed to the invading virus, they “are activated to express RNA or proteins that disable the invading pathogen.” This type of plant defense is known as RNA silencing, or RNA interference. This method had great success when applied to the papaya industry. A scientific study of this process concluded that “The GM papaya has saved the papaya industry in Hawaii, without any significant adverse effects to environment and human health during the application for more than a decade.” Figure IV.3 shows an advertisement that praises the effectiveness of the RNA silencing techniques for saving the Hawaiian papaya industry.

Scientists have examined the possibility of adverse outcomes when transgenes are utilized to fight plant disease. One possibility is that the transgenic cassette might migrate to wild papaya plants. Thus far no such outcomes have been found. Another possibility is that these transgenic plants could interact with existing viruses to create new virus epidemics. Another possibility is that genome segments from the virus inserted into the plant might recombine with the genome of a different virus that enters the plant. To date, no such recombination effect has been observed. Finally, it is possible that amino acid sequences in the transgene cassette could cause new allergens or could enhance existing allergens. Again, no such allergens have been observed in the plants that have obtained disease resistance through RNA silencing techniques.

The inducement of disease resistance by transgenic techniques appears to have many benefits and very few drawbacks. However, one study examined the effects of transgenic papaya and traditional papaya on the properties of the soil where it was planted. It reported that “Transgenic papaya altered the chemical properties, enzyme activities, and microbial communities in soil.” Thus, it is important that these RNA silencing techniques be studied to ensure that no adverse outcomes occur in the future.

C. Insect-Resistant Crops

Crops and commercial plants suffer losses from insect predation. Over the centuries, many different methods were employed to kill insect pests. In the middle of the 20th century, chemical insecticides were developed. These included aldrin, DDT, chlordane and parathion. They proved highly effective in killing insects; however, as chronicled by Rachel Carson in her book Silent Spring, they had very harmful effects with respect to animals, and the chemicals were either proscribed or highly regulated. So, an important development occurred when it was discovered that resistance to specific insects could be built into plants by transgenic methods.

It was realized in the 1970s that the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis or Bt possessed proteins that seemed to be toxic to some insects. Bt was widely studied and eventually it was understood that at least 200 types of Bt proteins are toxic to specific insects. When Bt forms spores, proteins called crystal endotoxins or Cry proteins form around the spore. Some of those proteins are toxic to specific insects. The insecticidal properties are shown schematically in Fig. IV.4. When an insect or larva ingests part of the plant containing the Bt proteins, those proteins are activated by enzymes in the insect’s gut. The protein toxins are released and eventually cause the gut to rupture, killing the insect.

To date, Bt seeds have been developed for a number of different plants such as maize, soybeans, eggplant, cotton, potatoes, tomatoes and tobacco. In each case, researchers needed to find proteins that would bind to receptors in the gut of a specific insect. Humans and many other insects do not have Cry toxin receptor sites, so Bt plants are generally regarded as safe for humans to consume. Studies by both the EPA and the FDA have concluded that the endotoxins expressed in Bt plants do not pose a health hazard to humans. Note that Bt crops provide an attractive alternative to traditional spraying of crops by insecticides. The Bt toxins are highly specific, which means that broad-spectrum insecticides do not have to be used with these plants. It is possible that Cry proteins could induce allergenicity in animals, even if they do not have the same effect on humans. We are not aware of any examples of this occurring with Bt transgenic crops.

The Case of StarLink

In 1995, the chemical company AgrEvo purchased Plant Genetic Systems. That company had developed a transgenic corn product that expressed a toxic protein from Bt called Cry9c. The company sold the Bt corn under the trade name StarLink. That product had two different transgenes – one of those was a transgene that was resistant to the herbicide glufosinate; a second transgene encoded the Cry9c protein, which is toxic to the European corn borer. Before StarLink corn was released in the U.S., its properties were reviewed by three different regulatory agencies: the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA); and the Animal and Plant Inspection Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, or APHIS/USDA. In 1997, the EPA issued a permit for Plant Genetic Systems to carry out field tests of StarLink. Later that year, Plant Genetics Systems asked the EPA to allow them to use transgenic corn for feed that would be consumed by cattle or chickens.

In May of 1998, EPA approved the registration of StarLink corn to be used as feed for animals, but not for humans. One year later, AgrEvo requested that the EPA authorize StarLink for direct human consumption. The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act of 1996 (FIFRA) gave the EPA oversight on genetically modified organisms that contained insecticidal proteins. Under that act, GMOs that incorporated transgenic insecticidal proteins were classified as a new type of pesticide, called plant-incorporated protectants or PIPs. In Feb. 2000, the EPA Scientific Advisory Panel on FIFRA issued a report stating there was “No evidence to indicate that Cry9c is or is not a potential food allergen.” On the basis of that ambiguous report, the EPA did not allow StarLink corn to be consumed directly by humans. (It is not at all clear that the different U.S. federal agencies with responsibility to regulate different aspects of GMO foods even share the same criteria for approval.) Various environmental groups claimed that StarLink corn seeds would contaminate traditional seeds. After corn products from a market were tested for Cry9c proteins, some evidence for Cry9c proteins was found in taco shells. After this result was widely publicized, 51 people complained to the EPA that they had become ill after eating these tacos.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) investigated these complaints and studied the blood of people who had claimed illness after eating the tacos. They concluded that there was no evidence that the adverse reactions were caused by allergies to StarLink corn. Nevertheless, there was a great deal of concern that the transgenic seeds had somehow commingled with traditional maize seed. A survey done on studies of Bt insecticidal plants concluded that “The majority of the laboratory studies that were performed to test the infectivity and toxicity of Bt commercial products have indicated that these products are safe.” It is believed that “-omics” studies, to be described in Section V, might provide more specific information on the precise differences between transgenic plants and traditional ones.

In summary, all three of these uses for transgenic plants prove to be effective in protecting the plants from competing with weeds, predation by plant diseases, or attacks by insects. With some caveats, we know of no significant health effects to humans or from the use of transgenic products. There do not yet seem to be any significant association with disease or allergies from transgenic plants. In particular, transgenic products that protect against specific plant diseases seem to be highly successful in those cases where these products have been used. Also, Bt plants that are toxic to certain insect pests appear to be quite effective. The toxins produced by these plants are very specific; they kill only targeted insects and not other more desirable species.

However, all of these transgenic products have drawbacks that will eventually limit their use. The first is that they are not sustainable in the long run. When these products are used, the targets – weeds, plant diseases, or insects – will eventually evolve to produce resistance to these products. For plants engineered with herbicide resistance, farmers will have to employ more and more herbicide, or to supplement Roundup with other herbicides. Similar long-term effects will arise for plants resistant to certain diseases or plants that are toxic to targeted insects. A second concern is that transgenic plants seem to be contaminating our stock of traditional seeds. At present, only a very small fraction of traditional seeds seems to be contaminated by the transgenic seeds, but it is extremely important that serious efforts be devoted to maintaining a supply of uncontaminated seeds.

The case of Roundup Ready seeds involves the business model adopted by Monsanto and others. The seeds are engineered so that the plants are resistant to a particular chemical herbicide – in the case of Monsanto (and the current owner of Roundup, Bayer) the seeds must be purchased every year from the manufacturer, and they must be used with the target herbicide. The question of the toxicity of Roundup to humans is a vexed one – as we will see in Section V, while the EPA classifies the active ingredient in Roundup, glyphosate, as “non-carcinogenic in humans,” the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization classifies glyphosate as having “sufficient evidence in experimental animals for the carcinogenicity.” While we accept the results of the cancer tests on mice cited by the EPA, we have little confidence that a company like Bayer would voluntarily report any studies that suggested problematic human health effects from Roundup.

Finally, it is not clear that transgenic products, particularly plants that tolerate certain herbicides, actually increase agricultural productivity. There are contradictory studies of productivity for these products – while some claim greater yields for Roundup Ready products, other studies find that yields are smaller for those plants. Also, over time these methods will become progressively less productive as resistance to these products evolves.

— Continued in Part II —