July 9, 2024

I. Background

Michael Crichton’s 1990 novel Jurassic Park and the movie franchise it inspired alerted the public to the development of scientific technology that is capable, in principle, of resurrecting extinct species. The movies also scared the public about potential impacts of human hubris in using their technical tricks to tinker with Nature. But humans are already tinkering with Nature, with dramatic impacts on both Earth’s environment (climate change) and biodiversity (6th mass extinction). Adopting new biotechnology to resurrect extinct species is the biological counterpart to geoengineering. In both cases, scientists ask whether they can exploit technology in further tinkering to mitigate some of the worst impacts of their prior tinkering. What could possibly go wrong?

In this post we will review some of the relevant bioengineering techniques, major advocates, ethical questions, and current and possible future projects in reviving extinct species, usually referred to as de-extinction. Our understanding of recent efforts to stave off extinction for some endangered species and to revive others that have gone extinct is informed by two excellent recent books: Resurrection Science by M.R. O’Connor and How to Clone a Mammoth by Beth Shapiro. In most cases, the resurrection projects envisioned deal with species closely related to other species still extant on Earth, meaning in general that the target species branched off from the related species within the past ten million years or so of evolution. So it pays to start by discussing how related species are understood to differ from one another.

Speciation:

Closely related species represent parallel, but distinct, evolutionary paths branching off from a common ancestor. Figure I.1 illustrates such branching points for elephants, mammoths, and mastodons, showing that DNA and other analyses reveal that today’s Asian elephants are the most closely related living species to woolly mammoths, one of the primary targets of de-extinction research. Genomic differences along those distinct paths may have been naturally selected to optimize adaptation to distinct environments and ecosystems, or they may simply represent alternative optimization strategies to survive environmental change. Differences in appearance (phenotype) and behavior between the related species are not solely determined by their divergent genomic paths. If they occupy different habitats, interactions with those environments may introduce epigenetic differences that influence whether certain genes are actually activated – expressed — or not.

The goal of natural selection is to increase the chances that individuals within a species can survive and reproduce. Reproductive efficiency is highest when individuals mate with others of similar (but not too similar – inbreeding is not successful in the long term) genetic makeup. The most successful matings increase the frequency in future generations of those genetic characteristics that made the mating successful in the first place. Distinct populations within a given species, whose reproductive success may be driven by different genetic variations, may thus gradually diverge over many generations. Interbreeding between the two populations may at first be suppressed by geographical separation or residence in distinct ecological environments. In general, they become viewed as distinct species when mating of an individual from one group with an individual from the other becomes largely unsuccessful, i.e., has low probability of producing surviving, non-sterile, offspring.

Mating between distinct but related species is not impossible. Mules are the sterile offspring of forced mating between a male donkey and a female horse. The offspring are useful to humans, but not especially useful to donkeys or horses. Neanderthals and homo sapiens overlapped geographically in parts of Europe and the Middle East during the last Ice Age and they occasionally mated successfully, producing non-sterile offspring. Hence, humans today typically share 1-4% of their DNA with the now extinct Neanderthals. Because of such occasional interbreeding, the line between separate populations or subspecies vs. separate species is not a sharp one.

The processes of speciation can lead to dizzying numbers of distinct species of some common animals. For example, there are nearly 8,000 known species of frogs and toads. Some of these have adapted to unique and highly localized habitats. One such endangered species, highlighted by M.R. O’Connor in Resurrection Science, is a tiny, yellow, pointy-nosed frog known as Nectophrynoides asperginis. These guys were found within the intense spray from a single powerful waterfall within a gorge deep inside the remote Udzungwa Mountains of Tanzania. They were discovered in 1996 as part of an ecological impact assessment for a Tanzanian project to convert that waterfall to a hydropower plant in a country desperately in need of more electrical power. The species had developed genetically to thrive in the unique microclimate formed over five acres of wetlands where an intense spray, winds and noise were created by that powerful waterfall hitting the local rocks. For example, “Biologists believe the frog’s combination of ultrasonic and visual communication was a survival mechanism that helped them find reproductive partners” in that deafening environment, which was essentially free of predators.

The story of the “spray” frogs of Tanzania is one among thousands of stories in which human needs are taking over habitats that have spawned unique species. Efforts to stave off extinction of the frogs are ongoing in captivity, with no guarantee of success at survival when new generations of the frog are reintroduced in the wild. Why should we care about saving one among nearly 8,000 species of frogs and toads found around the world? Only because this is one among thousands of such stories. Human activities are responsible for much of what is perceived as the ongoing Sixth Mass Extinction of species on Earth.

Causes of extinction:

More than 99% of all species known to have existed on Earth have gone extinct. Some of them failed to reproduce with sufficient efficiency to keep their species going in competition with many other species for food and resources. Other extinct species succumbed to overhunting by predators or to diseases that spread more rapidly than the species could adapt to by genetic mutations. Some were simply replaced by daughter species that evolved to adapt better to a changing environment. Some went extinct because they lost their habitat or their food supplies dwindled or disappeared. Some succumbed to changes in Earth’s climate to which they could not adapt.

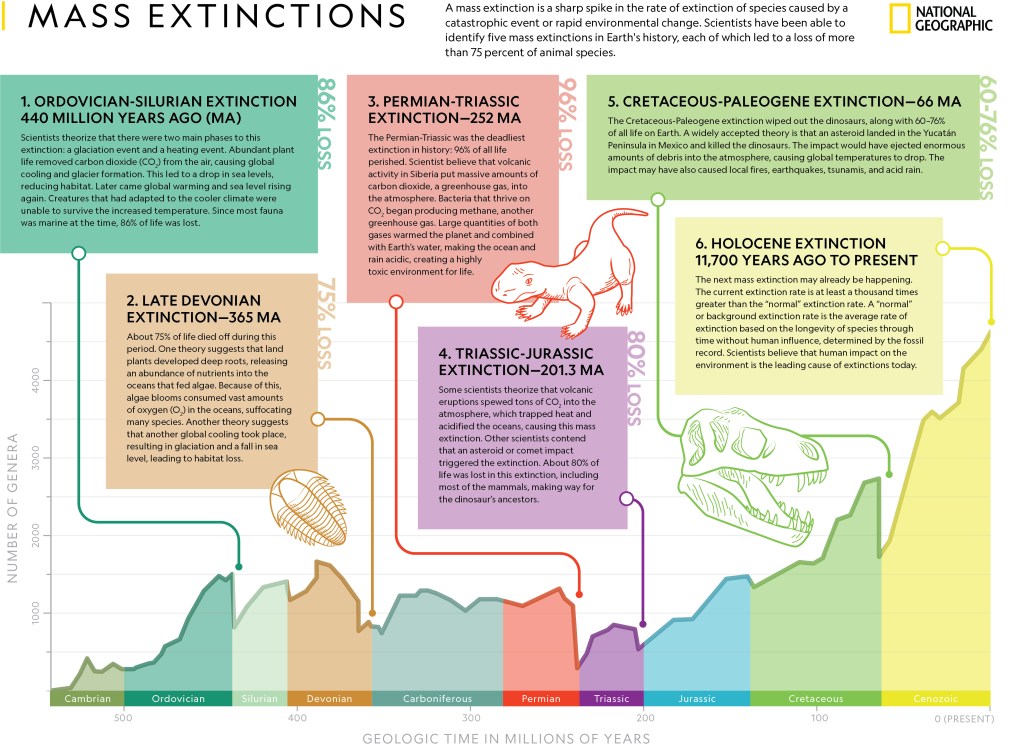

Extinctions are a natural feature of evolution and they occur continuously throughout Earth’s geological history. But the paleohistory revealed by study of fossils highlights five mass extinction episodes when extinction rates went through dramatic spikes, which occurred abruptly on geological time scales summarized in Fig. I.2. Educated guesses regarding likely causes of each mass extinction episode, summarized in Fig. I.2, are based on other aspects of Earth’s paleohistory that can be gleaned from geological and fossil studies. The first two of these mass extinctions were most likely associated with the emergence of abundant new plant life that either removed significant fractions of the warming carbon dioxide atmospheric blanket surrounding Earth, causing massive global cooling, or soaked up much of the oxygen in the oceans, suffocating other marine life. The next two may have been caused by massive volcanic eruptions that spewed so much carbon dioxide and methane that the climate warmed too rapidly for most species to adapt.

Only in the case of the most recent of these five paleohistory episodes, the one occurring 66 million years ago that wiped out all but airborne dinosaurs, along with 60-76% of all life on Earth, has detailed evidence been uncovered to illuminate the cause. It seems to have been triggered by a massive asteroid impact in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, which in turn caused other catastrophes. But a recent study has also shown that contemporaneous with that asteroid collision there were also massive volcanic eruptions in the Deccan Traps of Western India. The combination of the asteroid impact and the volcanic eruptions would have drastically altered atmospheric conditions over a very short period of time.

Today we are seeing species extinctions at a thousand or more times the historical background evolutionary extinction rate of less than one extinction per century out of each 10,000 species. We seem then to be in the midst of a Sixth Mass Extinction, this time associated most directly with human activities. Humans, of course, are predators to many animal species and that, to some extent, represents an evolutionary norm. But humans are also unique in hunting not only for food, but also for luxury clothing, for sport, and for trophies, with advanced weapons. For example, illegal poaching within the allegedly protected Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya has recently driven the northern white rhino to near-extinction in the wild with support from “international criminal networks operating with the help of corrupt politicians. The crime syndicates are feeding a seemingly insatiable hunger in countries like Vietnam and China, where the nouveau riche view rhino horn for medicine or hangover prevention as a status symbol. A kilogram of rhino horn reportedly fetches up to $100,000 [in 2013] in these countries, much more than gold.”

But the greatest impact humans are having on present-day extinctions is from taking over and developing natural habitat, from polluting the atmosphere and waterways, and from emitting greenhouse gases responsible for the ongoing global warming and climate change. For example, “[h]umans have already transformed over 70% of land surfaces and are using about three-quarters of freshwater resources. Agriculture is also a leading cause of soil degradation, deforestation, pollution, and biodiversity loss. It is diminishing wild spaces and driving out countless species from their natural habitats, forcing them to clash with humans for resources or leaving them vulnerable.” Animals and birds viewed as a threat to farming are often killed by humans. Other species are threatened by their competition with invasive species introduced into new habitats by humans. Still others, such as the Yangtze River dolphin, have been driven to extinction by extensive human use and pollution of their habitat.

One example of the impact of human-caused global warming is the imminent death of coral reefs in many parts of the globe. The disappearance of coral reefs threatens the 25% of all marine species that have life stages dependent on coral reef systems. Fracturing ice shelves and melting sea ice caused by global warming are threatening polar bears in Arctic regions. The increasing frequency of severe storms, forest fires, heat waves, and droughts worldwide are jeopardizing many other species. And within ecosystems, the disappearance of some species has cascading effects threatening others that depended on them for food or symbiosis. In short, humans are altering Earth’s environment, climate, and biodiversity as no species before has ever done.

Biotechnology:

Another way that humans are unique animals is that they experience both guilt and sadness over their impacts on the natural world. Many humans are working assiduously on conservation efforts to save currently endangered species. We will review some of these efforts, with both positive and questionable outcomes, in Section II of this post. But a sense of guilt may also form one part of the motivation for a handful of humans who are seeking passionately to adapt recent advances at the forefront of biotechnology to actually revive at least some already extinct species. We will discuss those biotechnology advances in some detail in Section III, but we mention them briefly here.

Among those biotechnology approaches is cloning, the technique first used to create an exact replica of a living mammal in 1996, when scientists at the Roslin Institute in Scotland created the cloned sheep Dolly (see Fig. I.3). Dolly, who was born and lived for seven years, developed as a fetus in the womb of an unrelated ewe who contributed none of her own DNA to Dolly. Cloning relies on extracting a living somatic cell from the animal to be cloned and injecting it into the nucleus of an unfertilized egg cell, taken from another (female) animal, whose own nucleus has been removed. Somatic cells, each containing pairs of chromosomes donated by each parent, constitute the majority of cells in a mature body. They are distinct from germ cells – egg cells or sperm – which contain only single chromosomes to be donated to offspring in the act of fertilization.

Cloning is a very inefficient process because mature somatic cells are specialized, with only those genes expressed that are essential to the function of that particular cell. But when an embryo develops it generates stem cells, which are unspecialized but capable of developing during gestation into the wide variety of cells that will be needed in a developing baby. Conversion of the injected somatic cell within the modified egg into an embryonic stem cell is highly inefficient: the Roslin Institute team created 277 embryos of which only one successfully developed into Dolly. The second of the new biotechnology approaches relevant to de-extinction stems from the discovery in 2006 by Shinya Yamanaka and Kazutoshi Takahashi in Kyoto, Japan of a process to convert a somatic cell to a type of stem cell – called an induced pluripotent stem cell, iPSC — in a tissue culture in a lab more efficiently than within a donated egg. For this discovery, Yamanaka shared the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for the discovery that mature cells can be reprogrammed to become pluripotent.” iPSCs are important in attempts to revive extinct species, but even more so for regenerative medicine, where they can give rise to mature cells to replace any somatic cells in a patient that have succumbed to damage or disease, and they can do this without the politically sensitive need to destroy any embryos.

The third relevant advance allows at least a partial sequencing of ancient DNA extracted from remains of animals that lived long ago. Beth Shapiro, the author of How to Clone a Mammoth, heads the Ancient DNA research laboratory at the University of California, Santa Cruz. This is done using the same techniques as those used to map the genome of humans and many other living species, but is far trickier because DNA begins to deteriorate and fragment as soon as an organism dies.

If one can extract at least a partial map of the genome of an extinct species, then one can move on to de-extinction by applying the fourth of the relevant biotechnology breakthroughs: CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, the efficient DNA “find, cut and paste” technique for which Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier shared the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry (see Fig. I.4). We have described the CRISPR action and some its applications in detail in a previous post and will provide reminders in Section III of this post. In the context of reviving extinct species, CRISPR-Cas9 provides a method to edit the DNA in a cell – perhaps an iPSC to be injected into an unfertilized egg – taken from a living animal to replace some genes with ones extracted from ancient DNA of a closely related, but now extinct, species. For example, a research group in the company Colossal Biosciences, co-founded by distinguished geneticist George Church of Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, is currently working to implant some woolly mammoth genes, and hence, characteristics, within an iPSC generated from a living Asian elephant. Their hope is that an edited mammoth-like elephant embryo can survive to birth and beyond after gestation within the womb of a living female Asian elephant.

No Jurassic Park:

Because of the degradation of DNA over time, there is a technical limit to how ancient a species can have its DNA recovered. The current record is partial genome reconstruction for an animal that lived 700,000 years ago. That means it is currently technically possible to get DNA information on extinct species from the geologic Pleistocene epoch, which spanned Earth’s last Ice Age, the time of Neanderthals and woolly mammoths. It is not possible to reconstruct dinosaur DNA from fossils as the dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago (see Fig. 1.2). Scientists cannot actually create a Jurassic Park. In the movie, dinosaur DNA was alleged to have been extracted from dinosaur blood contained within an ancient mosquito trapped in amber, i.e., fossilized tree resin. While it is true that ancient insects are occasionally trapped rapidly within amber and physically preserved remarkably well, the weight of research evidence from ancient DNA teams suggests that ancient DNA is not preserved in amber, despite early claims to the contrary.

It is, however, within the realm of possibility to create a Pleistocene Park. In fact, it has already been established as a 160 square kilometer wildlife preserve in Siberia by Sergey Zimov of the Russian Academy of Sciences Northeast Science Station. Zimov is eagerly awaiting the eventual release of resurrected woolly mammoths, and possibly other Ice Age animals (Fig. I.5), to populate his park and help to convert tundra to grasslands.

Motivations:

Even with the extraordinary biotechnology tools mentioned above, regenerating an entire extinct species, or something close to it, would be no mean feat. It will already be a considerable breakthrough to generate a single embryo with a genome resembling that of a long-dead species. But then that embryo must survive through implantation in the womb of a female animal of a related species. For some calibration, the survival rate of human embryos produced by in vitro fertilization up to successful implantation in the uterine lining of a female of the same species is only about 30%. Will a female of a related species provide all the hormones and nutrients needed by that embryo during gestation? If the animal survives birth, will it survive infant mortality? The most successful attempt to date to revive an extinct species was the cloning of a Pyrenean ibex (or bucardo) using a living somatic cell preserved from the last surviving bucardo shortly before it died in 1999. According to Beth Shapiro’s account, “Only one of 208 embryos that were implanted into the surrogate mothers survived to be born. Unfortunately, the baby bucardo had major lung deformity and suffocated within minutes.”

And of course, producing one living representative of an extinct species is hardly enough. One must generate a community with enough genetic diversity in their DNA makeup that one could anticipate successful mating and propagation of the species, with enough genetic flexibility to adapt to future environmental changes. One must also prepare a habitat resembling that for which the species was originally adapted. And who is to train these infants in the methods of survival – finding appropriate food and shelter, evading predators, etc. – within the habitat prepared for them, when there are no living adults of their species who have survived in that environment? If they are trained by humans in a protected environment like a zoo, will they survive release to the wild? And if they survive release, can we be sure that the conditions that drove them to extinction in the first place no longer exist?

Given these daunting challenges, what motivates excellent scientists and entrepreneurs to work on such de-extinction? For some it represents one way of fulfilling what they see as humans’ sacred duty to protect biodiversity on Earth. Some of the funds are provided by a non-profit organization named Revive & Restore, which was started in 2013 by San Francisco Bay area writer Stewart Brand and his wife, entrepreneur Ryan Phelan. Brand first came to prominence in the 1960s when he co-founded and edited the Whole Earth Catalog, a counterculture magazine and product catalog focused on “self-sufficiency, ecology, alternative education, do-it-yourself” and holistic medicine and lifestyles. In announcing his intentions for Revive & Restore in a 2013 TED talk, Brand said “humans have made a huge hole in nature in the last 10,000 years. We have the ability now, and maybe the moral obligation, to repair some of that damage.” The organization funds projects not only in de-extinction, but also in applying biotechnology to “enhance conservation outcomes, from restoring genetic diversity to facilitating adaptation.”

Some of the scientists involved in the field, including Beth Shapiro and George Church, are focused on reviving species that can help to restore endangered ecosystems. Church’s focus on the woolly mammoth, for example, is based on the hope that mammoth-like elephants, genetically adapted to survive in cold environments and reintroduced in Sergey Zimov’s Pleistocene Park, can help to restore steppe grasslands in Arctic regions and to ameliorate the thawing of the Arctic permafrost, which threatens to release even more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere than fossil fuel burning has yet done. But the impact revived species will have on ecosystems is far from certain. As Beth Shapiro points out in How to Clone a Mammoth, “When a species goes extinct, the ecosystem in which it lived changes to adapt to its disappearance. If the extinction took place many thousands or possibly only even hundreds of years ago, it may be that reintroducing that species would actually destabilize whatever new equilibrium that ecosystem had achieved.”

But there is something quixotic, perhaps even cruel, about a program to revive passenger pigeons, which were once superabundant on Earth but driven to extinction near the turn of the 20th century largely by human hunting. Or to bring back a species once successfully adapted to life in the frigid north of Earth’s last Ice Age, during an era of global warming. So one must also see in the motivations something of the nature of scientists that was articulated by J. Robert Oppenheimer in his own defense during the 1954 Atomic Energy Commission hearings that revoked his security clearance: “…when you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead and do it and you argue about what to do about it only after you have had your technical success. That is the way it was with the atomic bomb.” In other words, Oppenheimer was effectively arguing that the Manhattan Project scientists would have gone ahead to develop the atomic bomb in a crash program even if they had known that the U.S. government was purposely exaggerating the threat that the Germans were rapidly advancing toward the bomb themselves. George Church and others are currently intent on achieving the technical bombshell of de-extinction; they and others will figure out the next steps later.

We will describe several of the most prominent de-extinction projects under way in Section IV of this post and will discuss conditions under which de-extinction may make sense to pursue in Section V.

II. Attempts to save endangered species

Given the daunting challenges to de-extinction, it is not surprising that there are far more extensive efforts underway to save currently endangered species from extinction. We will describe several of these efforts in this section. The challenges, successes and failures in our attempts to save endangered species may assist us in determining the most promising methods that can be used in de-extinction efforts. If de-extinction efforts succeed in reviving individual members of an extinct species, they will still face all the difficult and costly challenges we describe below in transitioning to a viable, self-sustaining population.

An early effort to protect endangered species arose from the publication of Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, Silent Spring. We summarized this in an earlier post on our blog. Carson pointed out the dangers of widespread use of pesticides. She advocated for a holistic approach to the environment, and she pointed out the importance of insects in our ecosystem. Carson claimed that dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane or DDT accumulated in the bodies of apex predators, and she suggested that birds such as eagles, hawks and ospreys were experiencing reduction in numbers that may have been associated with deleterious effects from DDT that caused eggshells to thin.

The chemical industry fought vigorously against Carson’s claims, but after the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1972, its director William Ruckelshaus declared that DDT was a carcinogenic hazard for humans, and he banned sales of that chemical in the U.S. The effect on the population of raptors was quite dramatic. Numbers of eagles, hawks and ospreys increased rapidly. In hindsight, it appears that DDT was interfering with the ability of these birds to reproduce. In this case, although the use of DDT had adverse effects on animals, the birds still existed in sufficient numbers that they could rebound once the chemical was no longer in use. The examples we choose for trying to save endangered species – the whooping crane, the California condor, the gray wolf, the northern white rhinoceros, and the Florida panther — are more dire. In the case of the whooping crane and the condor, the number of existing birds had dwindled to a handful before captive-breeding efforts were undertaken. In the case of the gray wolf, it had been exterminated in the Western U.S. before efforts were launched to re-introduce the wolves in that area.

II.A The Whooping Crane:

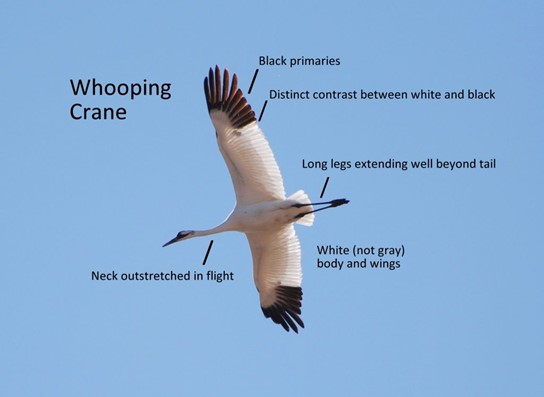

The whooping crane (Grus americana) is one of two crane species in North America, the other being the sandhill crane. The whooping crane is the tallest bird species in North America, with birds ranging from 1.24 to 1.6 meters in height. A typical wingspan is between 2 and 2.3 meters. Adult whooping cranes are white, with a red crown and a long, dark pointed bill, while immature whooping cranes are a cinnamon-brown color. Figure II.1 shows a pair of adult whooping cranes with an immature crane. When cranes are in flight, they keep their long necks straight and trail their black legs straight behind them. When in flight, the black wing tips are clearly visible. Figure II.2 shows a whooping crane in flight; it points out distinguishing features by which one can identify the whooping crane.

Whooping cranes nest on the ground in raised areas in a marsh. In late April to the middle of May, a female will lay one or two eggs in the nest. Both parents take part in rearing the young. If two eggs are hatched, the parents will devote nearly all their efforts to one of the young, with the result that it is rare that more than one young crane survives.

Scientists believe that whooping crane populations were never very large. Before Europeans colonized the midwestern United States, it is estimated that the whooping crane population was over 10,000 birds, and whooping cranes were found in marshes and wetlands through much of the North American Midwest. However, the numbers of whooping cranes decreased radically through the 19th and early 20th century. By 1870, the number of whooping cranes had dropped to around 1,400 birds. By 1938, there were just 15 adults in a single migratory flock, plus about 13 birds in a non-migratory population in Louisiana. There were several reasons for this population decline. The most notable was the loss of plains wetlands habitat, as farmers plowed prairie grasses and drained marshes. However, cranes also suffered losses to a number of predators such as bobcats and coyotes and occasionally eagles; whooping cranes were also hunted for their plumage and their eggs were stolen by collectors.

In the 1950s, whooping cranes were featured on a U.S. postage stamp, shown in Fig. II.3, that highlighted wildlife conservation. But by this time it was felt that the whooping crane had reached a point where only drastic measures could save them from extinction. This resulted in a coordinated effort between the U.S. and Canada, since cranes wintered in areas such as Texas, Louisiana and Florida, while many of them summered in Wood Buffalo National Park in Alberta, Canada. Several whooping cranes winter at the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and surrounding areas in the San Antonio Bay area of Texas.

In 1967, the whooping crane was listed by the U.S. as threatened with extinction and it was further listed as endangered in 1970. In 1973, with the passage of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), whooping cranes were grandfathered into the list of endangered species. In Canada, whooping cranes were listed as endangered under the Canada Species Act of 1974, and subsequently in 2003 under the Species at Risk Act. There is a detailed International Recovery Plan by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; it is updated every five years and involves a collaborative plan with the Canadian government.

Despite the designation of whooping cranes as endangered and prohibitions against hunting these birds, the number of cranes in the wild continued to decrease. After considerable debate, it was decided to transfer eggs from Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park to the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center near Laurel, Maryland. In 1989, it was decided to split the captive flock of whooping cranes into two groups, with a second group at the International Crane Foundation in Baraboo, Wisconsin. The captive crane populations have been relatively successful, with the numbers of birds and eggs increasing steadily.

There is a significant difference between raising captive birds, and successfully re-introducing birds into the wild. In captivity, male and female cranes are carefully studied, both from the point of view of genetics and to learn their personal characteristics. Potential mates are introduced to one another and encouraged to mate. Frequently, eggs from an adult couple are removed from the nest and placed in a nest of a juvenile or infertile couple. When those eggs are hatched, the foster parents care for them. The fertile parents are then induced to produce one or even two more pairs of eggs. The last pair of eggs remain in the nest of the parents. Artificial insemination is often used to maintain genetic diversity of the flock, and to provide an avenue to produce chicks between strongly bonded pairs who are not a good genetic match. Also, some of the eggs are placed in nests of ‘surrogate’ parents such as other species of cranes.

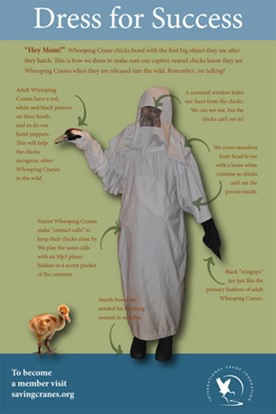

Once the chicks are hatched, they need to be reared and prepared to enter the wild. Most whooping crane chicks from either the Patuxent or Baraboo sites are eventually released into the wild. Other young cranes are sent to facilities with populations of captive cranes. Initially, some young cranes were reared by their surrogate parents from other species of cranes, or by human researchers. However, it was soon realized that baby cranes imprint on other types of cranes or on humans. This makes it difficult or impossible for the cranes to be released into a flock of wild whooping cranes. So, when a baby crane is hatched to a surrogate crane of a different species, the crane is taken away and reared by human volunteers. Those volunteers are dressed in a “crane costume,” so that the baby crane imprints on the image of an adult crane. Figure II.4 shows a volunteer dressed in a crane costume. The costume was designed by George Archibald, the co-founder of the International Crane Foundation. The costume is white, and one hand contains a sleeve that resembles the head of an adult crane. This will allow the young crane to be released into a flock of adult whooping cranes on which it is imprinted.

A novel approach was developed by pilots Bill Lishman and Joe Duff, who collaborated with a non-profit group called Operation Migration. Beginning in fall 2001, Lishman and Duff employed a technique they had previously used with Canada geese. After whooping cranes were hatched, they were trained to follow an ultralight aircraft, as shown in Fig. II.5. The cranes were then taken to their breeding grounds in Wisconsin. When it was time to migrate, the cranes followed the ultralight craft to their winter home in Florida. The next spring, the cranes returned to their breeding grounds in Wisconsin. The program was sufficiently successful that juvenile cranes that had been born in captivity were released directly into the flock of whooping cranes, where they could learn their migratory path from their peers.

Although the ultralight aircraft program was initially successful, over time the hand-raised and guided birds failed to reproduce in the wild. In January 2016, the US Fish and Wildlife Service decided to halt the ultralight program in favor of other methods for rearing. This program had 102 birds in 2018 and by 2020 the number had dropped to 86 birds.

Several whooping cranes have been transferred from the Florida non-migratory population to a non-migrating group in central and northeastern Louisiana. This population has been moderately successful through the introduction of a new technique. Some eggs have been laid by juvenile whooping cranes; however, these eggs are infertile. Researchers have noticed that although cranes generally lay two eggs, they focus their efforts on one of the hatchlings, and it is quite rare for both chicks to survive. Therefore, scientists remove one egg from a pair laid by an adult bird, and they substitute that egg for an infertile egg laid by a juvenile. When that egg hatches, the juvenile pair raise the chick as their own. This procedure has greatly increased the number of chicks that survive to adulthood. In 2020, there were 76 birds in the Louisiana non-migratory flock.

A major cause of whooping crane deaths in the Eastern migratory flock is from illegal hunting. In the first decade of the 21st century, approximately five of the 100 birds in the Eastern Migratory Population of cranes were illegally killed. An illustrative example was the case of Wade Bennett of Cayuga, Indiana. On March 30, 2011, Bennett and a juvenile companion shot and killed a whooping crane called First Mom, so named because she and her mate were the first captive raised and released pair to successfully raise a chick to adulthood in the wild. After killing First Mom, Bennett took a photo of him holding up her body. We don’t know whether Mr. Bennett or the judge who sentenced him was more of an idiot. For killing a rare and federally protected whooping crane, Bennett was fined $1 plus court costs of $500, and was sentenced to probation. It is estimated that it costs roughly $100,000 for every crane that is raised and then re-introduced to the wild.

However, the non-migratory flock in Louisiana has suffered even more deaths from illegal shootings. Roughly 10% of the first 150 cranes released to this population were shot and killed. In January 2016, a Texas man was fined $25,000 for killing a whooping crane. He was also barred from possessing firearms for a five-year period. When he violated his probation, he was sentenced to 11 months in jail.

As of 2020, the efforts to save the whooping crane appear to have succeeded to some degree. We now have an Eastern migratory flock plus three re-introduced non-migratory groups. In addition, there are captive populations of whooping cranes at locations such as “the Calgary Zoo, the International Crane Foundation [in Baraboo, Wisconsin], the Audubon Species Survival Center in Louisiana, and other sites in Florida, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Texas.”

However, we should note that several attempts to get whooping cranes to mate, raise their young and release them into the wild have failed. These include:

- Attempts to have whooping crane young be raised by other crane species failed because the whooping cranes imprinted on the cranes that raised them. This prevented them from forming their own flocks and reproducing with other whooping cranes. In 1975 a joint US – Canadian project attempted to create a new whooping crane flyway from Idaho to New Mexico. The project placed whooping crane eggs in the nests of sandhill cranes and allowed the sandhills to raise the whooping cranes and teach them to migrate. This resulted in several adult whooping cranes who followed a successful flyway, but because of imprinting on the sandhill cranes, the birds failed to reproduce with other whooping cranes, so this project was discontinued in 1989.

- A similar failure occurred when human volunteers attempted to raise young cranes. Once again, the young whooping cranes imprinted on the humans and would not socialize and migrate with other whooping cranes, until the volunteers adopted the “crane costume” shown in Fig. II.4. The use of crane costumes has allowed humans to raise young whooping cranes in captivity. Most of those cranes have been released into the wild, with a few cranes placed in colonies at various zoos, or in research flocks in various states.

- In 1993, a joint US – Canadian project attempted to establish a non-migratory flock of whooping cranes near Kissimmee, Florida. Over an 11-year period 289 cranes were released to this population. However, this project was plagued with high mortality rates and low reproductive success in the flock. Eventually the US Fish & Wildlife Service moved some of the Florida whooping cranes to a non-migrating flock in Louisiana, and by 2020 only nine cranes remained in the Florida population.

- A more successful project involved the creation of a new flyway east of the Mississippi River. Cranes were reared in captivity and taught to follow an ultralight aircraft as shown in Fig. II.5. The cranes were taken to a breeding territory in central Wisconsin. When it was time for the cranes to migrate, they followed an ultralight aircraft to their winter home in Florida. After the whooping cranes had learned their migration route, and the population had stabilized, other young whooping cranes were released directly into the existing flock, where they would learn the migratory route from their peers. By June 2018, there were 102 birds in this eastern migratory flock; by 2020 this number had decreased to 86 birds.

Many of the whooping cranes in the eastern migratory flock gather at the Goose Pond Wildlife Fish and Wildlife Area in south central Indiana. Over 8,000 acres of farmland and surface strip mines have been converted into wetlands, grasslands and woodlands habitat. The level of the shallow wetlands is maintained by a series of levees. Goose Pond has become a critical part of the eastern migratory flyway. Every spring and fall, hundreds of thousands of shorebirds, raptors and songbirds pass through the Goose Pond refuge. It is common to see vast flocks of snow geese, American pelicans and sandhill cranes during their migration. In addition, the Goose Pond area is the only location in Indiana where we have seen groups of short-eared owls. We have seen two or three whooping cranes at Goose Pond (a first sighting of a whooping crane for both of us who write this blog). This was a big thrill as whooping cranes are truly majestic birds. They are frequently found amongst vast flocks of sandhill cranes. Sandhill cranes are large birds, but whooping cranes tower over them.

In conclusion, the efforts to save the whooping crane from extinction seem to have resulted in small flocks of whooping cranes in the wild, with one established eastern flyway between Wisconsin and Texas, and one non-migratory population in Louisiana. Efforts to breed whooping cranes in Maryland and Wisconsin have been quite successful. After a series of projects were attempted, scientists have been able to produce significant numbers of eggs and to hatch and rear many young whooping cranes. From a low of about 20 whooping cranes, we now have about 800 whooping cranes. Some of these are situated at the crane breeding establishments in Laurel, Maryland and Baraboo, Wisconsin. Other birds are held at zoos and other research parks, in addition to the wild populations of whooping cranes that either migrate or are stationary.

One challenge is to maintain genetic diversity in the whooping crane population. Because the crane population dwindled to such a low number, scientists are taking proactive methods in attempts to provide genetic diversity in the whooping crane flock. When male and female cranes are paired off, the birds are carefully selected based on their “genetics, behavior, age and rearing history.” Artificial insemination is also used, so that even females who are otherwise not able to mate can produce offspring. This helps to manage genetic diversity and to increase the fertility of eggs. Although most of the cranes that are hatched are released into the wild, young cranes that are ‘genetically valuable’ may be retained in the captive-breeding population.

Despite the successes of this program, the wild populations are still at risk. Whooping cranes are threatened by a number of natural predators. They also have limited reproductive success in the wild. They are subject to natural disasters like tornadoes, hurricanes and wildfires. Cranes are also vulnerable to disease. Researchers are worried about the H5N1 strain of highly pathogenic avian influenza or HPAI, which has recently been sweeping the globe. They are closely monitoring cranes in captive-breeding programs and in the wild. At present, whooping cranes do not seem to have been seriously affected by the H5N1 virus; however, the cranes are vulnerable to viruses like H5N1.

And whooping cranes in the wild are still killed by illegal hunters. Until penalties are enacted that will prevent hunters from shooting these birds, we can expect hunting to decimate herds of whooping cranes. Finally, these conservation efforts are extremely costly. It is estimated that it costs $100,000 per bird to produce a wild flock of whooping cranes. These high costs will continue each year, until the whooping cranes reach a point where they are reproducing successfully in the wild, and managing to avoid the various perils that threaten their existence. Unless these costs can be significantly reduced, efforts to maintain flocks of whooping cranes will be competing with other worthy environmental projects. We note that the training of whooping cranes using ultralight aircraft was halted after the Trump administration discontinued funding for this project.

II.B. The California Condor:

The California Condor (Gymnogyps Californianus) is a New World vulture and is the largest land bird in North America. The wingspan of the condor can reach 3 meters. Although we know of at least four prehistoric types of North American condors, the California condor is the only surviving member of its species. As shown in Fig. II.6, the California condor has a bald head and neck, with a ruff of feathers around the base of the neck. Condors are among the longest-living birds, with a lifespan of up to 60 years. The condor’s plumage is black. When they are flying, their feet are extended straight back, and white triangles are visible on the underside of the wings. This is shown in Fig. II.7, which features a soaring condor viewed from below. Note that the condor has numbered plates on both wings; condors that have been released from captivity all have numbered plates so that individual birds can be easily recognized. Condors tend to float on thermals in canyons; some can often be seen in the Grand Canyon in Arizona. To take off, they jump off a cliff, flap their wings a few times and then soar through the air. When floating, they can go for long periods of time without flapping their wings. They reach top speeds of 40 miles per hour and take about 16 seconds to complete a circle when they are soaring.

Condors feed on carrion. They prefer to feed on large mammals such as deer, sheep, horses, cattle, pigs or cougars. But they may also eat carcasses of smaller animals such as rabbits or squirrels. They are even known to eat whales or sea lions. Condors can go as long as two weeks without eating; when they do have a meal, they eat ravenously. They can store up to 1.2 kg of meat in their crop, for later digestion. When condors locate a carcass, they are able to scare away nearly all other scavengers. The only exceptions are bears and golden eagles; although condors have twice the weight of the eagles, the talons of the condors are straight and blunt, and are significantly less sharp than those of the eagle. In fact, the talons of the condor are more suited for walking than for grasping; this has led some scientists to question the presumed close evolutionary relationship between vultures and condors.

At one time, condors roamed across the canyons of western North America. At this time,the birds fed off the carcasses of large apex predators. However, as giant mammals died off, the number of condors decreased. Another reason for the decline of condors is that they reproduce extremely slowly. Female condors lay a single egg and often lay an egg every other year. The parents tend to their chicks for between 6 months and one year. The numbers of condors plummeted in the late 20th century. Other factors in the decline of condors included poaching, lead poisoning (more about this later), collecting of condor eggs, the loss of habitat, and effects of chemicals such as DDT.

In 1987, when the total number of condors reached 27, it was decided to remove all the condors and rear them in captivity. The San Diego Wild Animal Park and the Los Angeles Zoo were leaders of a captive breeding program that included some other participating zoos. The condor breeding program utilized several features of the whooping crane breeding effort. Researchers realized that if an egg was removed from a condor nest, the female condor would often lay a second egg, and sometimes even a third egg. Using this “double-clutch” technique, many more baby condors were produced. When adult condors were not available to raise a chick, it would be raised by humans using puppets that resembled the head of an adult condor. Figure II.8 shows a condor chick being fed by a human with a condor head puppet.

The project to breed and release condors, the California Condor Recovery Program, is an example of cooperation between federal and state governments, the Mexican government, and a number of partners in condor recovery. All of this is coordinated by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). In 1992, the USFWS began reintroducing captive-bred condors to the wild. To date, condors have been released in three general areas, shown on the map of Fig. II.9. The first area is in canyons in southern and central California; a second area includes the Grand Canyon in Arizona and Zion National Park in Utah. A third area of release is in northeastern Baja California. Although condors roam for very long distances in search of food (they can travel up to 250 km in a day), they remain in these general areas year-round and do not migrate.

Just like the whooping crane recovery program, the captive-breeding program for condors has been a big success. In May 2024, it was estimated that there were now 561 California condors, with about 2/3 of them released in the wild and 1/3 in captive breeding programs. However, despite the relatively large number of condors in the wild, California condors are still listed as Critically Endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. This is because of the very low rate of reproduction of condors, and because the condors are still threatened by various factors. One of those factors is collisions of condors with power lines. However, the captive-breeding program teaches young condors to avoid both power lines and humans.

Perhaps the biggest threat faced by condors in the wild today is lead poisoning. When condors eat animals that have been shot with lead-based ammunition, the lead bullets fragment and leave shards of lead in the carcass. When condors consume those animals, lead accumulates in the bodies of the birds and can prove fatal. As lead poisoning is currently the number one cause of death of condors, legislation to ban lead-based ammunition (which is currently the case only in California) would greatly benefit condors, as well as other birds such as vultures, eagles and hawks.

Another risk factor for condors is ingestion of microtrash, small bits of trash such as shards of glass, bottle caps, or tabs from pop cans. When people leave microtrash in the wild, condors can pick them up and either ingest them or, worse, feed them to their young. Effects of microtrash are currently the leading cause of death among baby condors. Other risk factors faced by California condors are poaching and bird flu. As more wind farms are constructed, collisions with wind turbines may become a significant risk factor in the future.

One of us (TL) was visiting the Grand Canyon in about 2010. A notable sight was watching large birds float, apparently effortlessly, among the thermals in the Canyon. We mentioned to a park ranger that we were enjoying the vultures soaring through the canyon. The ranger asked us “By chance, did the ‘vulture’ have a number plate on its wing?” We remarked that it did (see Fig. II.7). “That was no vulture,” replied the ranger, “that was a California condor.” We were overjoyed to see this magnificent bird, back from near extinction. On the morning that we left the Grand Canyon, we decided to re-visit the cliff site where we had seen the condor. Alas, there were no condors in the canyon. However, we noticed a crowd of people at the cliff edge about 100 yards away. When we joined this crowd, we saw seven condors sitting on a large rock at the edge of the cliff. We were thrilled to see these condors up close. However, about two minutes later, a park ranger shooed the birds away with an air horn. He explained that the condors needed to avoid humans. If they came in contact with condors, tourists would feed the birds and they would no longer forage for carrion.

Like the whooping crane effort, the condor recovery program has been quite expensive. The US and state governments have currently spent about $35 million on the program; it continues to cost about $2 million per year. Despite the impressive numbers of captive-reared birds that are released, the California condor program is still subject to potential setbacks, or to unforeseen threats that could still decimate this effort. It is also possible that future administrations will cut the funding for this effort.

II.C Gray Wolves:

Gray wolves are somewhat unique, in that there are countries with large wolf populations. For example, Russia is estimated to have 300,000 gray wolves (with large uncertainty) and Canada has 60,000 wolves. Alaska has between 8,000 – 11,000 gray wolves. However, there were almost no gray wolves left in the lower 48 states, as packs of gray wolves had been extirpated in the American West by the 1940s. A coalition of farmers and hunters had deemed the wolves a pest and had systematically wiped out packs of these animals. However, wildlife ecologists saw the existence of packs of the gray wolf (Canis lupus) as essential to a healthy ecosystem. The gray wolf was seen as a necessary apex predator to re-establish a balance that was currently lacking.

The idea of reintroducing gray wolves in the continental U.S. had been broached for some time; however, the impetus for carrying out wolf reintroduction was given a major boost with the passing of the Endangered Species Act in 1973. In 1980 five Mexican gray wolves, the last known wild gray wolves in the continental U.S., were captured and were enrolled in captive-breeding programs at zoos and research facilities. For 16 years, wolves were bred at these facilities. In 1998, the first gray wolves were reintroduced into the wild in states that had no existing wolf packs. Three packs of wolves were released into the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest in Arizona, and 11 gray wolves were released into the Blue Range Wilderness Area in New Mexico. Figure II.10 shows a gray wolf in a holding pen, prior to its release in Yellowstone National Park.

The captive-breeding and wolf reintroduction program has been fairly successful. By March 2024, there were at least 257 wolves in Arizona and New Mexico. And there are 380 wolves still in captive-breeding populations.

Starting in 1995, gray wolves were reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park (YNP) in Wyoming and into Idaho. Figure II.11 shows a pack of wolves in Yellowstone National Park following their reintroduction. As we will see, reintroduction of wolves has always been an extremely controversial effort. Scientists and ecologists strongly believed that Rocky Mountain ecosystems had been significantly skewed with the lack of the apex predator in that region. There were also Great Lakes states such as Minnesota, Michigan and Wisconsin where scientists claimed that reintroduction of wolves could restore a balance in the ecosystem. As an example of imbalance, ecologists pointed to the vast overpopulation of elk in YNP, and the damage that elk had caused to various species of plants and trees in that area. Although coyote had largely filled in the niche left by the wolves, the coyote could not control the elk population. Coyote, on the other hand, had seriously diminished the number of foxes, pronghorns, and wild sheep, and had eliminated altogether the beaver.

On the other hand, ranchers and hunters were vehemently opposed to reintroduction of wolves. A number of compromises were made in an attempt to mollify the anti-wolf lobby. For example, the reintroduced wolves were designated an “experimental, non-essential” population under the Endangered Species Act. This allowed farmers to kill wolves that strayed onto their land. We will discuss the objections of these groups to wolves below.

Although they were in the minority, the opponents formed a united front in opposing the release of wolves in the West. In a 1985 poll, “74% of visitors to Yellowstone National Park thought wolves would improve the park, while 60% favored reintroducing them.” However, after their release into the wild, gray wolf populations in North America increased, and in states where they had been killed off, wolves seemed to be establishing a foothold. However, as we will see, several states in the American West are currently determined to eliminate nearly all wolves in their state.

Figure II.12 shows the location of wolf packs in the greater Yellowstone National Park region, as of 2002. Each color represents a different pack of gray wolves. The boundaries of Yellowstone National Park, Grand Teton National Park, and the Gros Ventre Wilderness are indicated. However, at present we are uncertain about the future of these wolf packs. The reintroduction program included a protected region for wolves outside the boundaries of YNP. However, in the past few years Wyoming has refused to maintain that wolf-protection region. This means that wolves living in the area surrounding YNP, or venturing outside the boundaries of that park, could be killed. Margie Robinson, staff attorney for wildlife at the Humane Society of The United States, stated that “Nearly 30 years after wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park, wolves in the region are once again in danger of extinction.”

Opposition to Reintroduction of Wolves:

As we pointed out, the reintroduction of gray wolves in the American West has always been controversial. In particular, groups of farmers and hunters have been consistently and viscerally opposed to the reintroduction of wolves. So, the program of reintroduction of gray wolves remains a polarizing issue. The viability of wolf packs in the American West now depends on which political party is in power. If Donald Trump is elected in 2024, we can expect protections on wolf populations to be cut back or eliminated altogether.

After wolves were reintroduced into the American West, they formed packs, and the numbers of wolves in the wild increased significantly. But in 2021, wolves in Idaho, Montana and parts of other states were removed from the Endangered Species Act due to a congressional rider that was attached to a “must-pass” budget bill. Also in 2021 “conservative state lawmakers in Idaho, Montana and Wisconsin seized wolf management authority from trained wildlife professionals and reembarked on the age-old war on wolves.” Figure II.13 shows a group of hunters at an anti-wolf rally in Bozeman, Montana. As we will see, these conservative Western lawmakers authorize the killing of wolves in the most cruel ways imaginable. In Wyoming, wolves had been delisted from the Endangered Species Act protections in 2017. Wyoming’s Department of Game and Fish allows wolf killing by virtually any means, “including running them over with snowmobiles and incinerating pups and nursing mothers in dens.”

In 2022 the superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, Cam Sholly, asked Montana Governor Greg Gianforte to restore a wolf buffer zone that had existed around Yellowstone National Park. Not only did Governor Gianforte refuse to restore the buffer zone, Gianforte himself “had been cited for illegally trapping and shooting a wolf near the former buffer zone without completing the required trapping-education program.”

In February 2022, U.S. District Judge Jeffrey White ruled that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had failed to show wolf populations could be sustained in the Midwest and portions of the West without protection under the Endangered Species Act. A ruling near the end of the Trump Administration had removed protection for wolves under the ESA. The ruling restored ESA protection for much of the United States. In particular, protection for wolves was restored in the Great Lakes region, and especially in the state of Wisconsin. In 2021, a wolf hunt in that state during the wolf breeding season greatly exceeded the state’s quota of 119 wolves; 218 wolves were killed in just a 63-hour period. However, Judge White’s ruling did not apply to the states of Idaho, Wyoming and Montana, because of the 2021 law passed by Congress that removed protection for wolves in those states.

It should be noted that the arguments put forward by hunters and farmers are by and large specious. The following arguments were put forth by anti-wolf groups. First, they claimed that children would be killed by wolves while waiting for school buses. We know of no such deaths in any state following reintroduction. Then, they claimed that livestock herds would be slaughtered in tremendous numbers by wolf packs. This argument was shown to be inconsistent with the data. From 1987 to 2007, depredation of cattle and sheep by wolf attack amounted to 0.04% of cattle losses and 0.01% of sheep losses. Furthermore, in 1987 the group Defenders of Wildlife established a “’wolf compensation fund’ that offered to pay a rancher market value for any stock that was lost to wolf depredation.” More recently, Defenders of Wildlife has transitioned to a program that advocates for farmers to use nonlethal methods to control wolves; this includes removing carcasses to avoid attracting scavengers, use of lighting, adoption of guard dogs for herds, and increased human presence near herds.

In Yellowstone National Park, the number of elk has decreased significantly since the reintroduction of gray wolves. However, the elk population before wolves was extremely large and unsustainable. At one point in time, officials had allowed roughly 5,000 elk per year to be killed in Yellowstone, since the elk population was far above a sustainable level, and the alternative seemed to be starvation. After the culling procedure stopped, the elk population in Yellowstone had soared. Elk had grazed on trees such as aspen and willows at dangerously high levels. After reintroduction of wolves to YNP in 1995, the numbers of elk have decreased significantly, and this vegetation is now recovering rapidly. Other desirable animals such as beaver and red fox have seen increases in population, which ecologists attribute to the role of wolves in decreasing the population of coyotes. However, the presence of wolves also caused the elk to change their behavior. The elk herds tended to remain in areas where they were less likely to be subject to attacks from wolves. At the same time, the elk became more difficult to spot, making it harder for hunters to find the elk.

At one time, large herds of elk would leave Yellowstone National Park in the fall, in order to reach fields at lower elevations where food was more prevalent. There were areas where fences from farms outside YNP provided a relatively narrow corridor where elk could migrate. When the elk left the park area where hunting was prohibited, hunters would sit in their trucks and slaughter the elk as they migrated. After this practice was prohibited, hunters blamed the wolves for decreasing the number of elk that could be shot.

The story of gray wolves in North America shows how difficult it is to reintroduce apex predators into an ecosystem. Farmers and hunters in those areas have formed a powerful political coalition that opposes the release of wolves in their states. In the case of farmers, the claim that wolves will wipe out their livestock appears to be largely mythical, as the number of cattle and sheep lost to wolves is rather small. However, it appears that on occasion, a lone wolf or pack of wolves will begin to prey on livestock. In those cases, farmers are allowed to kill wolves found on their ranches. In other cases, a single wolf or a wolf pack will be captured and relocated to an area far from the farm.

There are reasons to be wary of reintroducing wolf packs into regions where they come into contact with humans. Although we know of no cases of humans being killed by wolves, there is always that possibility. Even though the number of wolves in the continental U.S. has reached relatively large numbers, wild wolf packs are still in jeopardy, particularly when a state (like Idaho or Montana) declares that its mission is to eradicate at least 90% of the gray wolves in their state. So, any efforts to reintroduce apex predators in order to restore balance to an ecosystem should be prepared for strong opposition from certain sectors of the population. In Section IV of this post, we will discuss efforts to re-introduce the passenger pigeon in North America and the Tasmanian tiger in Australia. One reason that these species became extinct is that farmers considered them a nuisance. If the passenger pigeon or the Tasmanian tiger survived de-extinction, one might expect groups of farmers to lobby for killing the birds feeding on their crops or the predators killing their livestock.

II.D White Rhinos:

The examples we considered above all relied at some point on breeding endangered species in captivity. But in other cases, conservationists hope to save species in the wild within allegedly protected animal preserves. The contrasting cases of two subspecies of white rhinoceros highlight the challenges in doing so.

In the early 1900s only a few dozen southern white rhinos survived in a remote preserve in South Africa. The South African government then banned rhino hunting and by the 1960s the animals numbered more than 2,000. The numbers strained the capacity of the preserve where they were located, so many were shipped to zoos around the world. By 1980 there were more than 3,000 southern white rhinos worldwide.

The northern white rhinos are genetically distinct from the southern white rhinos, separated by about a million years of evolution. In the early 1980s fewer than a hundred northern whites existed in the wild. But attempts to grow the populations within animal preserves in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Garamba Preserve) and Kenya (Ol Pejeta Conservancy) have been unsuccessful in outdueling poachers, who kill the rhinos for their horns, which are very highly valued in several Asian countries. The governments of these African countries have, at the very least, a laissez faire attitude toward the poachers. As of January 2024 only two northern white rhinos remain on Earth, at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy, and both of them are females (see Fig. II.14).

Yet all hope is not yet lost for the northern whites. Scientists have collected numerous northern white rhino tissues over the past decades. In several cases, somatic cells from these tissues have been converted to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). The saved cells are preserved in San Diego’s Frozen Zoo. The iPSCs can be converted to any type of cell, including sperm cells. Those sperm cells can be used to create northern white rhino embryos via in vitro fertilization using egg cells extracted from the two remaining female northern whites. IVF has recently been demonstrated to work for southern white rhinos, although the female who carried the successful embryo unfortunately succumbed to disease 70 days into the pregnancy.

II.E Florida Panther:

Pumas once had large populations in the southeastern United States, but they were hunted over centuries to near extinction by settlers who viewed them as dangerous predators. By the 1970s they were confined to a small stretch of Florida, where they are known as Florida panthers. A search commissioned by the World Wildlife Fund determined that there might be twenty or thirty remaining panthers “living off deer and feral hogs in the areas around Lake Okeechobee and south into the Everglades.” The Florida Panther Recovery Team was launched in 1976 to save the Florida panther from extinction. While the number of panthers has grown since then, they continue to be endangered by ever increasing urban sprawl and traffic, and they suffer from very low genetic diversity and low sperm quality among the males.

In 1992 a specialist group decided that the best route forward to stave off extinction of the Florida panthers was “to translocate individuals from a wild population of cats and bring them to Florida where their genes could mix with the Florida panthers.” In other words, they sanctioned increasing genetic diversity by producing hybrids with a distinct subspecies endemic to Texas. The decision was one of two that led the U.S. federal government to relax its previous policy that the Endangered Species Act could not be used to protect hybrids of species or subspecies.

M.R. O’Connor recounts the result: “After the translocation [of eight female cougars from Texas], three of the Texas females died before they could reproduce. The remaining five mated with Florida panther males and produced healthy kittens. Until then the total number of Florida panthers had fluctuated between roughly nineteen and thirty animals. By 2008 there were an estimated 104…The cats quickly demonstrated a renewed vitality.” Increasing genetic diversity among dwindling, isolated, endangered subspecies by encouraging hybridization with related but geographically distinct subspecies is now an increasingly common element of efforts to save endangered species. On the other hand, there is little remaining wild place for a panther population in the southeastern U.S., so the chance of dwindling genetic diversity and potential extinction in the future remains for these animals.

The collection and preservation of tissue samples from individual members of endangered species promises another method to increase genetic diversity in the future. iPSCs generated from the frozen cells can be used in IVF procedures for still living species, just as they might in the future be used to try to revive northern white rhinos. Endangered animals that now spend their lives in zoos around the world, where they are fed daily by zookeepers, may not be able to survive release into the wild, but they can still be valuable sources of tissue cultures for the Frozen Zoo and help thereby to save or revive their endangered wild species-mates.

— Continued in Part II —