August 3, 2023

I. introduction

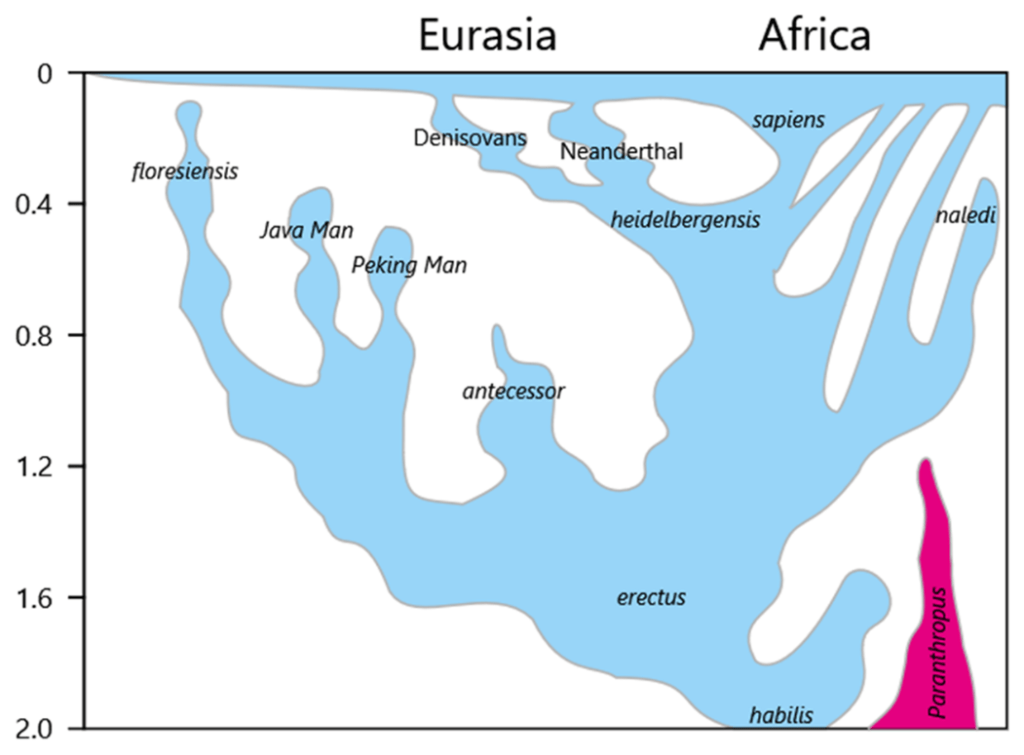

Fossil evidence tells us that homo sapiens have been around on Earth for more than 200,000 years. But human civilizations have been around for only roughly 7000 years. The launch of civilizations was not so much a matter of evolution of humans’ social behavior, but rather was a result of the Earth climate stability that emerged after the end of the last Ice Age. As illustrated in Fig. I.1, homo sapiens emerged, along with Neanderthals and Denisovans, as distinct evolutionary branches from the earlier hominin homo heidelbergensis (see Fig. I.2). Starting about 70,000 years ago, in the early throes of the last Ice Age, some homo sapiens migrated from various locations in Africa, following Neanderthals and Denisovans into Eurasia. This was a period not only of significantly colder Earth temperatures than the present, but also of extensive climate variability.

The peak of the last Ice Age, the so-called Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) occurred roughly 21,500 years ago. At that time the northern third or so of North America and Europe were covered in ice sheets and mountain glaciers were common in Africa and South America. Earth surface temperatures were, on average, about 5°C cooler than today. Global sea levels were about 400 feet below modern levels, since a great deal of ocean water had been transformed through precipitation into ice sheets. The conditions made it difficult for many animal and plant species to survive and for hominins to find food.

Neither the Neanderthals nor the Denisovans survived the Ice Age; in fact, they seem to have gone extinct even before the LGM. But homo sapiens did. The reasons for human survival are still subjects of research, but speculation centers on the genetic advantages that contributed to more effective communication among humans, crafting of stone tools and weapons, and more advanced social webs, including among different early human settlements.

But the launch of human civilizations in a form somewhat similar to what we think of today as “civilization” awaited the advent of agriculture, which was facilitated by the stabilization of Earth’s climate after the end of the Ice Age. Anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow, in their excellent recent book The Dawn of Everything, use recent archaeological discoveries to cast considerable doubt on the conventional narrative that the dawn of agriculture led, directly and inevitably, to the onset of personal property, wealth inequalities, and states with hierarchical governing structures. But farming, animal domestication, and reliable food production were indeed the linchpin of human civilizations that adopted a variety of forms of self-organization and self-government. We rely heavily on Graeber and Wengrow’s book for our discussions of prehistoric human societies.

Human civilizations have thrived during an epoch of unusually stable Earth climate, known as the Holocene, which began about 11,700 years ago. But that stability is now seriously threatened by human-caused global warming, tending toward producing Earth temperatures higher, on average, than humans have ever previously had to deal with. If homo sapiens were adaptable enough to survive the last Ice Age, it is likely that our species will also survive the ongoing global warming. But it is legitimate and timely to ask what damage the warming may do to a number of current human societies.

While the current warming is a truly global phenomenon, there have been throughout the Holocene regional, fairly sudden, climate changes whose effects on human societies we can study via archaeology in order to gain some insight for how such changes affect society. A number of well-established human societies have collapsed over time, some lost to conquest, natural disaster, or disease. But in other cases, climate change was the triggering, or at least threat-multiplying, factor. What climate stability giveth, climate instability may taketh away.

In this post, we will examine what is known of human settlements during the last Ice Age and during the Neolithic period following its end. We will review how the first substantial cities arose and how some early, and even more modern, societies collapsed as a result of regional climate changes. Based on the prehistoric and historic evidence, as well as the ongoing effects of human-caused global warming, we can then speculate about worst-case scenarios in which complex natural and human interactions threaten human societies in the warming 21st century and beyond.

II. homo sapiens in the ice age

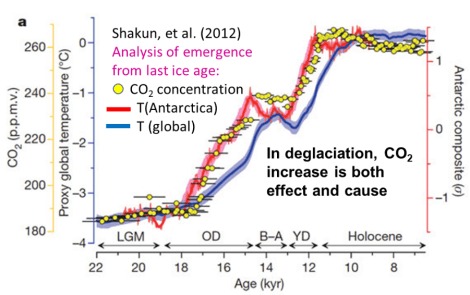

Figure II.1 shows inferred features of Earth’s climate over a time span from the last glacial maximum (LGM) to well past the start of the temperature-stabilized Holocene epoch. The red curve and yellow points represent, respectively, the Antarctic temperature and carbon dioxide concentrations extracted from the chemical composition of Antarctic ice cores, as a function of depth. The blue curve represents a proxy reconstruction of global mean temperatures deduced, in part, from oxygen isotope ratios in Greenland ice cores and in deep ocean sediments. The data suggest that emergence from the last Ice Age began by warming of the southern hemisphere oceans, as a consequence of Earth orbit changes. Carbon dioxide released from those warming oceans into the atmosphere may have provided a positive feedback mechanism to enhance the warming. The blue curve indicates that there was a time lag of about a millennium before the northern hemisphere followed the warming trend, as ocean currents slowly carried the warming waters northward, as carbon dioxide from southern atmospheres slowly diffused to the north, and as the northern ice sheets gradually receded. In Eurasia, where we have the most archaeological evidence of how humans lived during this period, it remained quite cold until 12,000 years ago or so.

Graeber and Wengrow discuss recent archaeological evidence that exhibits the rich societal structures of some of the human settlements during this extended cold period in Eurasia. For example: “In Europe, between 25,000 and 12,000 years ago public works were already a feature of human habitation across an area reaching from Kraków to Kiev. Along this transect of the glacial fringe, remains of impressive circular structures have been found that are clearly distinguishable from ordinary camp-dwellings in their scale (the largest were over 39 feet in diameter), permanence, aesthetic qualities and prominent locations in the Pleistocene landscape. Each was erected on a framework made of mammoth tusks and bones, taken from many tens of these great animals, which were arranged in alternating sequences and patterns that go beyond the merely functional to produce structures that would have looked quite striking to our eyes, and magnificent to people at the time. Great wooden enclosures of up to 130 feet in length also existed, of which only the post-holes and sunken floors remain.”

An even more monumental example of public works was uncovered in the Germuş Mountains of southeastern Turkey, comprising “great T-shaped pillars, some over sixteen feet high and weighing up to a ton, which were hewn from the site’s limestone bedrock or nearby quarries. The pillars, at least 200 in total, were raised into sockets and linked by walls of rough stone. Each is a unique work of sculpture, carved with images from the world of dangerous carnivores and poisonous reptiles, as well as game species, waterfowl and small scavengers. Animal forms project from the rock in varying depths of relief: some hover coyly on the surface, others emerge boldly into three dimensions.”

Discoveries such as these, along with those of contemporaneous “princely” burials of selected, honored individuals ornamented with extensive artwork of the time, provide evidence of social groupings that go far beyond the traditional description of prehistoric bands of loosely organized primitive human hunter-gatherers with no hierarchy. Members of some of these communities may well have subdivided into small bands for seasonal foraging for sparse food and hunting of woolly mammoths and other game with stone weapons they developed.

But the evidence suggests that in other seasons some of those bands gathered into more concentrated settlements, where they presumably had ritual feasts on the wild resources different bands had captured, but also produced time-consuming artwork and developed sufficient hierarchical organization to lead, plan and implement the construction of massive public works. Analogous seasonal organizations of society – with small bands to carry out hunting and food gathering in high seasons, while more concentrated and hierarchical settlements gathered off-season to share the rewards — have also been recorded in early 20th-century anthropological studies of some indigenous groups in North and South America.

Even Ice Age humans thus appear to have been social beings, in addition to being adaptable and innovative. Graeber and Wengrow stress that they also appear to have been politically self-conscious beings, in the sense that they freely chose different societal organizations to suit seasons highlighted by different dominant tasks. Perhaps this political consciousness – this gathering into larger groups and sharing experiences when it was deemed useful — also helped homo sapiens to survive the Ice Age, while their Neanderthal and Denisovan cousins succumbed.

But their human settlements remained small, isolated, and possibly transitory and migratory. Furthermore, the similarity in monuments and tools among different settlements across Eurasia suggests that many humans migrated as nomads among, and were welcomed into, such settlements over time, carrying with them news of how things were done in other settlements. As far as we can tell from the archaeological record to date, this seemed to be the nature of Eurasian settlements until climate stability arrived, enabling the development of agriculture, the domestication of animals and plants, to provide more reliable, stable and storable sources of food, without the need to keep moving in response to shifting weather, ice cover, and plant and animal habitats.

III. the path to civilization

As seen in Fig. II.1, the LGM was followed by a rise in Antarctic temperatures by about 2°C over three millennia, and a similar rise in global temperatures after a delay to allow for warm southern waters and atmospheric carbon dioxide to drift northward and for the gradual receding of the northern hemisphere ice sheets. That rise was then interrupted by a significant dip in temperatures associated with an event known as the Younger Dryas (YD in Fig. II.1). That event is believed to have been caused by the fairly rapid melting of the Laurentide ice sheet that covered much of North America, leading to an influx of cold fresh water into the north Atlantic and to consequent disruptions of Atlantic Ocean currents. As shown in Fig. III.1, that dip cooled central Greenland by more than 5°C as the weakened Atlantic current slowed the circulation of warmer southern waters toward the north. It was followed, about 11,600 years ago, by an extremely rapid rise in Greenland temperatures by about 10°C over less than a single century, as Greenland ice accumulations increased and the Atlantic current was perhaps restored. The Younger Dryas should serve as a cautionary tale about the nonlinear nature of Earth’s climate and the strong sensitivity of regional climates to shifts in the thermohaline ocean currents, which are driven by differences in ocean temperature and ocean salinity in different regions of the globe.

Proxy measurements (see Fig. III.2) indicate that after the Younger Dryas global temperatures stabilized about 10,000 years ago, setting the stage for human agriculture and human civilization. Humans have flourished during an unusually stable, ten-millennium, moderate climate period in Earth’s history, during which the global mean temperature did not vary by more than about ±0.5°C, until the ongoing rapid global warming caused by human industrial activities. There were, however, regions of the globe that saw larger variations in temperature, as well as in rainfall and drought, during the Holocene era, and we will discuss some of these later.

Early Neolithic farming:

As Earth’s climate began to settle down, so, too, did humans as it became less necessary to chase one’s food over long distances. The early period of climate stability after the end of the Younger Dryas event is referred to as the Neolithic, or late Stone Age, era. It lasted, according to most accounts, up to the beginning use of metal tools around 3300 BC. The first fully developed Neolithic cultures appeared around 10,000 BC in the Fertile Crescent – the region often denoted as the “Cradle of Civilization,” where Mesopatamia arose, and encompassing parts of the present Iraq, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, and perhaps Egypt.

Among the very first cultivated crops appears to have been figs, remains of which were discovered in 2006 in a house in Jericho – one of the earliest known towns – dated to 9400 BC. The first cultivation of grains began several centuries later. The domestication of large animals began about 8000 BC. Settlements around these early Fertile Crescent agricultural regions “became more permanent, with circular houses…with single rooms. However, these houses were for the first time made of mudbrick. The settlement had a surrounding stone wall and perhaps a stone tower (as in Jericho). The wall served as protection from nearby groups, as protection from floods, or to keep animals penned. Some of the enclosures also suggest grain and meat storage.” Jericho is estimated to have contained a population of 2000 – 3000 people within its surrounding stone wall.

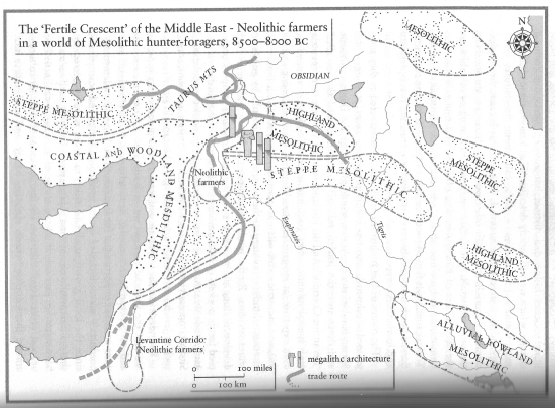

Graeber and Wengrow stress that the early adoption of farming was not at all uniform. Indeed, as indicated in the map in Fig. III.3, Neolithic farming communities were interspersed in the Fertile Crescent with Mesolithic (middle stone age) hunting and foraging groups that had ample available wild resources to satisfy their immediate needs. The stabilized climate proved a boon to foragers as well as to farmers. “The most vigorous expansion of foraging populations was in coastal environments, freshly exposed by glacial retreat. Such locations offered a bonanza of wild resources. Saltwater fish and seabirds, whales and dolphins, seals and otters, crabs, shrimp, oysters, periwinkles and more besides. Freshwater rivers and lagoons, fed by mountain glaciers, now teemed with pike and bream, attracting migratory waterfowl. Around estuaries, deltas and lake margins, annual rounds of fishing and foraging took place at increasingly close range, leading to sustained patterns of human aggregation quite unlike those of the glacial period, when long seasonal migrations of mammoth and other large game structured much of social life…Expanding woodlands offered a superabundance of nutritious and storable foods: wild nuts, berries, fruits, leaves and fungi, processed with a new suite of composite (‘micro-lithic’) tools. Where forest took over from steppe, human hunting techniques shifted from the seasonal coordination of mass kills to more opportunistic and versatile strategies, focused on smaller mammals with more limited home ranges, among them elk, deer, boar and wild cattle.”

Furthermore, as suggested in Fig. III.3, there seems from the archaeological evidence to have been frequent trade between the foragers and the farmers. Graeber and Wengrow point out that “Farming itself seems to have started…as one of so many ‘niche’ activities or local forms of specialization. The founder crops of early agriculture – among them emmer wheat, einkorn, barley and rye – were not domesticated in a single ‘core’ area (as once supposed), but at different stops along the Levantine Corridor, scattered from the Jordan valley to the Syrian Euphrates, and perhaps further north as well.”

The distinction between farmers and foragers began to be blurred. “At higher altitudes in the upland crescent, we find some of the earliest evidence for the management of livestock (sheep and goats in western Iran, cattle too in eastern Anatolia), incorporated into seasonal rounds of hunting and foraging. Cereal cultivation began in a similar way, as a fairly minor supplement to economies based mainly on wild resources: nuts, berries, legumes and other readily available foodstuffs.”

But early cultivation was still a long way from what we think of today as serious farming, with serious soil maintenance and weed clearing. Genetic studies of various wheat seed samples remaining from these early communities make it clear that “the process of plant domestication in the Fertile Crescent was not fully completed until much later: as much as 3,000 years after the cultivation of wild cereals first began.” This can be determined because domesticated wheat differs genetically from wild wheat, in that the domesticated version loses the ability to disperse its seed on its own. The foragers may not have wanted to devote the time needed for serious farming. And furthermore, they may have been most interested at first in cultivating cereals for the straw they used in lighting fires, constructing houses, making baskets, and the like, acquiring a taste for processing wheat for food only much later.

One of the largest of Neolithic towns was Çatalhöyük (Fig. III.4) in the wetlands of the Konya Plain in modern Turkey, first settled around 7400 BC and supporting a population of roughly 5,000. The evidence there, and also in the low-lying Neolithic settlements in the Levant, suggests that early farming was done on the margins of seasonally flooding lakes and rivers, relying on nature, rather than human effort, to prepare suitable soil. This type of farming benefited from the heavy monsoons and floods of the early Holocene period, which may have inspired the story of The Great Flood and Noah’s Ark. Graeber and Wengrow: “This was garden cultivation on a small scale with no need for deforestation, weeding or irrigation, except perhaps the construction of small stone or earthen barriers (‘bunds’) to nudge the distribution of water this way or that.” In other words, this seems to have been proto-farming on collective lands, without the advent yet of private property for more advanced soil management and storage of harvested surplus. This was hardly the oft-discussed Neolithic “revolution.” “The transition from living mainly on wild resources to a life based on food production took something in the order of 3,000 years.”

And since early Neolithic settlements were then based in muddy environments, the mud, too, became an important building material. The Neolithic towns, such as Jericho and Çatalhöyük, consisted of many, very similar, individual family houses, with no striking differences in size or importance, and with none of the monumental stone structures or violent imagery found in a number of the upland Mesolithic hunting/foraging centers, where inhabitants were also becoming less nomadic and more likely to settle in a single locale.

The Rise of Cities:

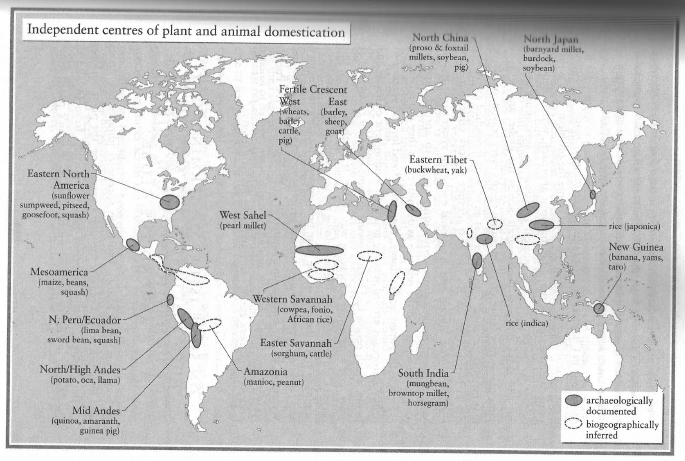

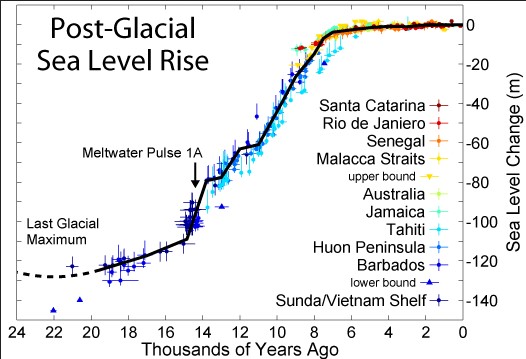

Several millennia passed before the domestication of crops and animals took root not only in the Fertile Crescent, but at a number of independent sites around the world, as indicated in the map of Fig. III.5. It is likely that global climate changes played a significant role in delaying the expansion of agricultural communities. While global temperatures settled down by about 10,000 BC, it took another several millennia for ice sheets to recede fully and for rivers and the seas to stabilize. During the first few millennia after the Younger Dryas, flooding of rivers was unreliable and sea levels were still rising rapidly (see Fig. III.6) as polar glaciers were rapidly melting. When these effects finally slowed down, and ocean and atmospheric currents became more reliable, wide and highly fertile floodplains were created along the Yellow River in China, the Indus River in modern Pakistan, the Tigris in Mesopotamia, and other rivers where the first urban civilizations were found.

The archaeological evidence supports the establishment of cities around local agricultural sites long before the existence of states with hierarchical governments: “Settlements inhabited by tens of thousands of people make their first appearance in human history around 6000 years ago, on almost every continent, at first in isolation…It’s not just that some early cities lack class divisions, wealth monopolies, or hierarchies of administration. They exhibit such extreme variability as to imply, from the very beginning, a conscious experimentation in urban form.” Recent archaeological evidence comes mostly from more mature stages of these early urban settlements, but they still “indicate how much older those cities may be than the systems of authoritarian government and literate administration that were once assumed necessary for their foundation.”

Each of the disparate sites in Fig. III.5 had its own specialty crops and domestic animals, and archaeological finds also reveal that each had its own distinctive culture. Farming communities continued, throughout most of the Neolithic period, to be interspersed with hunting and foraging communities. In some locations, like the Amazon valley in South America, inhabitants appear to have divided their time between the two, spending each rainy season in riverside villages to grow a variety of crops, which were then largely abandoned during the dry season, when the group would break up into small nomadic bands to hunt and forage.

And not all attempts at farming and coexistence fared well. Farming first spread to the central plains of Europe, in present-day Germany and Austria, around 5500 BC, carried by migrants from the southeast. But the excavation of mass graves from these sites, with bones showing “the telltale marks of torture, mutilation and violent death,” suggest the possibility of conquest or simple annihilation by invading groups, leading close to regional collapse between 5000 and 4500 BC. “Only after a hiatus of roughly 1,000 years did extensive cereal-farming take off again in central and northern Europe.”

But by no later than 2000 BC, as human population increased, “agriculture was supporting great cities, from China to the Mediterranean; and by 500 BC food-producing societies of one sort or another had colonized pretty much all of Eurasia…the largest communities were concentrated around lakes, rivers and coastlands, and especially at their junctures: delta environments – such as those of southern Mesopotamia, the lower reaches of the Nile and the Indus.”

It is probably no accident that many of the largest of prehistoric cities arose in river delta regions, with their newly reliable and fertile floodplains. As Graeber and Wengrow put it: “Comprising well-watered soils, annually sifted by river action, and rich wetland and waterside habitats favoured by migratory game and waterfowl, such deltaic environments were major attractors for human populations. Neolithic farmers gravitated to them, along with their crops and livestock…just over the horizon lay the open sea, and before it expansive marshlands supplying aquatic resources to buffer the risks of farming, as well as a perennial source of organic materials (reeds, fibres, silt) to support construction and manufacturing.” On the other hand, “Wetlands and floodplains are no friends to archaeological survival. Often, these earliest phases of urban occupation lie beneath later deposits of silt, or the remains of cities grown over them.”

Mid-neolithic climate stability may also have facilitated several eastern European “mega-sites” unearthed during the past half-century in present-day Ukraine and Moldova. These appear to have been sizable early cities, supporting populations of several thousand, built around the fertile black soil left behind by receding glaciers in the flatlands north of the Black Sea – the same fertility that makes modern-day Ukraine (when not at war with Russia) into a breadbasket for the world. They seem to have thrived from roughly 4100 to 3300 BC. According to Graeber and Wengrow, “The Neolithic people who settled there had travelled east from the lower reaches of the Danube, passing through the Carpathian Mountains. We do not know why, but we do know that…they retained a cohesive social identity…archaeological studies of their economy…suggest a pattern of small-scale gardening, often taking place within the bounds of the settlement, combined with the keeping of livestock, cultivation of orchards, and a wide spectrum of hunting and foraging activities.”

These Neolithic eastern European settlements comprise many individual houses built in concentric circular patterns around an empty region in the center, with “no evidence of central administration or communal storage facilities.” Graeber and Wengrow compare the layout of these Neolithic communities to that of self-organizing modern Basque societies in the southwest corner of France. In those Basque communities the circular layout is intended to emphasize that none of the inhabitants has a more important location than any other, and to facilitate a cyclic assignment of shared communal chores to each household around the circle in turn.

Technical aspects of farming and metal-working certainly benefitted from these mid-Neolithic environments, but there is little evidence to support the traditional narrative that cities with strong political hierarchies were the inevitable result of agriculture with improving technology, the acquisition of private property and wealth, and the need to provide protection for one’s land and livestock, and to manage one’s agricultural surpluses. Indeed, Graeber and Wengrow point out that “the largest early cities, those with the greatest populations, did not appear in Eurasia – with its many technical and logistical advantages – but in Mesoamerica, which had no wheeled vehicles or sailing ships, no animal-powered traction or transport, and much less in the way of metallurgy or literate bureaucracy.”

Governance and the rise of kingdoms:

Much of our modern perceptions about the beginnings of “civilization” are based on biblical accounts and archaeological explorations of Mesopotamia (see map in Fig. III.7). The Bible tells of kingdoms, and sometimes cruel autocratic leaders, in Babylon and Assyria. Victorian era archaeology did, in fact, reveal remnants of such biblical figures, along with: Hammurabi’s Code (Hammurabi ruled Babylon in the eighteenth century BC); clay tablets from Nineveh bearing copies of the Epic of Gilgamesh (fabled leader of Uruk, a city of tens of thousands where Cuneiform writing appears to have been invented); and the Royal Tombs of Ur (in southern Iraq, the site of the ancient Sumerian society), containing burial sites “where kings and queens unknown to the Bible were interred with startling riches and the remains of sacrificed retainers around 2500 BC.”

So, how did the relatively isolated mid-Neolithic farming communities of the Fertile Crescent lead to such strongly structured kingdoms? The earliest Mesopotamian cities, which sprang up around 4000 BC, present no evidence for monarchy. But starting around 2800 BC, monarchies appear to spring up everywhere in the region, marked by “palaces, aristocratic burials and royal inscriptions, along with defensive walls for cities and organized militia to guard them.”

Even during this dynastic period, there is evidence from preserved records, including the Epic of Gilgamesh itself, that the cities retained significant measures of self-government, with substantial involvement of the citizenry. “Popular councils and citizen assemblies…were stable features of government, not just in Mesopotamian cities, but also in their colonial offshoots (like the Old Assyrian karum of Kanesh, in Anatolia), and in the urban societies of neighbouring peoples such as the Hittites, Phoenicians, Philistines and Israelites…This was the case even in areas such as the Syrian steppe and northern Mesopotamia, where traditions of monarchy ran deep…So, far from needing rulers to manage urban life, it seems most Mesopotamian urbanites were organized into autonomous self-governing units, which might react to offensive overlords either by driving them out or by abandoning the city entirely.”

The first archaeological hints of Eurasian aristocracy show up around 3100 BC in the hills of eastern Turkey, on the fringes of what began as relatively small trading outposts of Uruk, initially established to follow the bureaucratic organization of that large city. This was after the dawn of the Bronze Age and the advent of metallic weapons. The rise of a warrior aristocracy is revealed by hill forts and small palaces and “for the first time also tombs of men who, in life, were clearly considered heroic individual of some sort, accompanied to the afterlife by prodigious quantities of metal weaponry, treasures, elaborate textiles and drinking gear…Unlike the isolated ‘princes’ and ‘princesses’ of the Ice Age, there are whole cemeteries of such burials…”

These initial “heroic” societies were aristocracies without any apparent centralized authority: “…all such groups explicitly resisted certain features of nearby urban civilizations,” such as writing and currency. They seem to have been consumed with contests, sometimes bloody, among heroic individuals seeking material wealth. Thus, Graeber and Wengrow conclude: “Aristocracies, perhaps monarchy itself, first emerged in opposition to the egalitarian cities of the Mesopotamian plains, for which they likely had…ultimately hostile and murderous feelings…” And that hostility, combined with the thirst for wealth among the warrior class and supported by Bronze Age weaponry, led to subsequent conquests and the establishment of monarchies throughout Mesopotamia.

But other parts of the globe saw quite different social arrangements in early cities. The Bronze Age, running approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC saw not only the beginnings of “heroic” aristocracies propelled by metal weapons, and the advent of writing in Sumeria and elsewhere, but also the first large-scale, planned cities. The best preserved of the Bronze Age cities is Mohenjo-daro in the Indus River valley in today’s Pakistan (see Fig. III.8). It seems to have begun around 2600 BC and to have lasted about 700 years (more about its demise in part II of this post).

Along with other Indus cities, such as Harappa (on the banks of the Ravi River, a tributary of the Indus), Mohenjo-daro seems from archaeological remains to have yet a different type of organization from the Mesopotamian or Mesoamerican settlements. According to Graeber and Wengrow: “Most of the city consists of the brick-built houses of the Lower Town, with its grid-like arrangement of streets, long boulevards and sophisticated drainage and sanitation systems (terracotta sewage pipes, private and public toilets and bathrooms were ubiquitous). Above these surprisingly comfortable arrangements loomed the Upper Citadel, a raised civic centre, also known…as the Mound of the Great Bath…a large sunken pool measuring roughly forty feet long and over six feet deep, lined with carefully executed brickwork…all constructed to the finest architectural standards, yet unmarked by monuments dedicated to particular rulers, or indeed any other signs of personal aggrandizement.”

The Bath seems to have been a public facility for purifying the body. Whether the Great Bath was open to all citizens or only to the wealthy or ascetics is unclear. But, “Over time, experts have largely come to agree that there’s no evidence for priest-kings, warrior nobility, or anything like what we would recognize as a ‘state’ in the urban civilization of the Indus valley.”

It is not known today if the Indus civilization was egalitarian, but Graeber and Wengrow at least entertain the possibility that the political structure of these early cities helped to inspire the organization of the first Buddhist monasteries in the 5th century BC, as is indeed suggested in some early Buddhist texts. These early monasteries “were meticulous in their demands for all monks to gather together in order to reach unanimous decisions on matters of general concern, resorting to majority vote only when consensus broke down.”

Meanwhile, archaeology in China has revealed a significant number of late Neolithic cities characterized by clear social stratification. “Already by 2600 BC we find a spread of settlements surrounded by rammed earth walls across the entire valley of the Yellow River, from the coastal margins of Shandong to the mountains of southern Shangxi…Many of the largest Neolithic cities contain cemeteries, where individual burials hold tens or even hundreds of carved ritual jades…in ancestral rites, the stacking and combination of such jades, often in great number, allowed differences of rank to be measured along a common scale of value, spanning the living and the dead…Burials in the early town cemetery of Taosi fell into clearly distinct social classes. Commoner tombs were modest; elite tombs were full of hundreds of lacquered vessels, ceremonial jade axes and remains of extravagant pork feasts.”

These studies of early human cities lead us to the following bottom lines. (1) The receding of the Ice Age glaciers and the stabilization of the seas and precipitation patterns led, by 4000 BC, to fertile floodplains and black soil north of the Black Sea that became sites for the emergence of the first substantial cities on various continents. (2) Cities in different regions appear to have chosen different paths to local self-governance and different choices along the egalitarian-to-stratified spectrum of social organizations. (3) There is little evidence for ‘states’ and kingdoms to have arisen before Bronze Age weaponry established a warrior class by the middle of the third millennium BC. Advanced weapons may have played a greater role than agriculture itself in leading to the hierarchical states we see in human history of the past several millennia.

— Continued in Part II —