June 22, 2023

IV. The recent surge of school library bans

Addendum to post on book banning, August 7, 2024:

This post describes a new wave of book banning, the result of right-wing agitation to remove books they view as objectionable from public-school (and sometimes public) libraries. In the post below, we note that book banners are generally in the minority. Thus, when groups such as Moms for Liberty attempt to take over school boards, they can often be defeated when the majority turns out to oppose the book-banning tactics. However, the state of Utah has figured out a way to make it easier for relatively small groups to impose their will on the citizens of that state. In 2022, Utah passed House Bill 374, “Sensitive Materials in Schools.” That bill allowed for books with “sensitive materials” to be banned in public or charter school libraries.

Until now, obscenity has been determined by a three-part test established by the federal court trial Miller v. California that includes the following criteria:

- The “average person” would find the material, on the whole, “appeals to prurient interest in sex.”

- The material is “patently offensive in the description or depiction of nudity, sexual content, sexual excitement, sadomasochistic abuse, or excretion.”

- The material, on the whole, “does not have serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.”

Under the Miller v. California test, material would not be considered obscene or pornographic if it could be shown to have serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value. However, in 2022 prior to HB374, Utah’s Alpine Valley School District, which consists of 21 grade schools and 4 high schools, had selected 275 books for review, based on complaints from a group called Utah Parents United that the books were inappropriate for children. Following the passage of HB 374, which was sponsored by Utah Rep. Ken Ivory, the 275 books were reviewed. The great majority of these books were found to have no objectionable content. However, an internal Alpine Valley library audit determined that 52 books by 41 authors “contain sensitive material … and do not have literary merit.” Of these 52 books, 42% “featured LBGTQ+ characters and/or themes.”

HB 374 appeared to be a powerful force that would prevent Utah public school students from reading this literature. However, Ken Ivory, the sponsor of that bill, felt that HB 374 was not having enough success in banning books that he found objectionable. So this year he sponsored amendments to HB 29, a bill that otherwise deals with Mental Health Support and Law Enforcement. Ivory’s amendments, now signed into law by Utah’s Governor, “clarify” how books should be reviewed and banned. Under HB29, if a book contains “objective sensitive material,” which includes descriptions of sex or masturbation, it could be banned by a school administrator without any prior review. And any book that had been banned by three Utah school districts, or two school districts and five charter schools, must be removed from all public school libraries statewide. According to the amendments’ sponsor Ken Ivory, HB29 was necessary to “create uniformity” across the state in determining what books would be allowed on the shelves. Ivory stated, “It’s time that we stand for the good and the clean and the pure and the powerful and the positive for our children; because that’s why we have public school.” The HB29 bill “was amended to allow the Utah State Board of Education to vote on whether to override a statewide ban.” However, the “objective sensitive material” test would mean that books, films or any other media could be banned from Utah public and charter schools regardless of the literary or artistic merits of the work.

At the beginning of August 2024, the state of Utah ordered all public schools to remove 13 books from classrooms and libraries. The 13 books were by 7 authors. All 13 of these books had been removed from the libraries in Davis and Washington districts, seven of those had been removed in Alpine and Nebo districts, and Jordan district had removed six of the books. Thus, five of the 41 school districts in Utah had forced the rest of the state to remove those books from their libraries. Another feature of the law stipulates that the banned books “may not be sold or distributed.” While most of these books will end up in dumpsters, some schools in Utah may actually end up burning banned books, which brings back uncomfortable images of book burnings in Hitler’s Third Reich.

Figure 1: Three of the authors of books that have been banned from all public school libraries in Utah in August 2024, under the criteria established in HB29. From L: Margaret Atwood; Judy Blume; Sarah J. Maas.

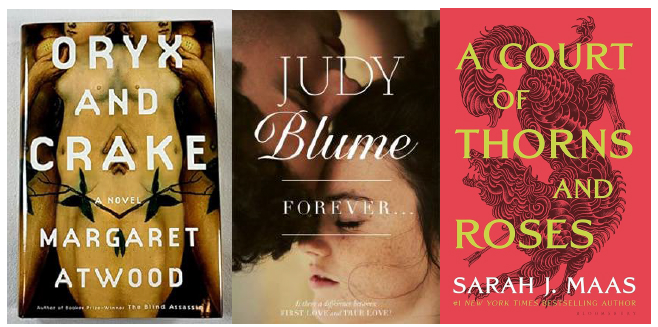

So, what are the authors and titles of the 13 banned books? Three of the authors – Margaret Atwood; Judy Blume; and Sarah J. Maas – are shown in Fig. 1. Fig. 2 shows three of the banned books. Six of the thirteen banned books in Utah were by Sarah Maas, who writes fantasy series for young adults. For example, one of her series re-told the story of Cinderella, in which Cinderella turned out to be an assassin aiming to kill the prince. As of 2024, Sarah Maas has sold over 38 million books and her work has been translated into 38 languages. Her books have won several awards from Goodreads, and her novels regularly appear in lists of the “Best Young Adult books” of the year, or of the decade.

Figure 2: Three of the 13 books that have been banned from all public school libraries in Utah, under the criteria established in HB29. From L: Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood; Forever … by Judy Blume; A Court of Thorns and Roses by Sarah J. Maas.

Two of the banned books were by Ellen Hopkins, who writes fiction for teens and young adults. At one time, Hopkins’ daughter was addicted to crystal meth and spent two years in prison. So Hopkins’ novels often feature teens who struggle with issues such as mental health, drug addiction and prostitution. Hopkins has won a Silver Pen award for emerging writers from the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame, and in 2015 she was inducted into that Hall of Fame. The difficult issues featured in Hopkins’ work has made her books some of the most frequently banned or challenged in the U.S. Four of her novels were included in the American Library Association’s list of the top 100 banned or challenged novels from 2000 to 2019.

One of the banned books was Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood. This was a science fantasy novel by one of the most acclaimed writers of this century. Atwood has won two Booker Prizes, the Arthur C. Clarke Award, the Franz Kafka Prize and a lifetime achievement award from PEN Center USA. She is probably best known for her novel The Handmaid’s Tale. Oryx and Crake is the first of a very well-reviewed trilogy of dystopian novels about the survival efforts of a small band of humans who remain after a global apocalypse triggered by a genetically engineered drug. Oryx and Crake was short-listed for the 2003 Man Booker Prize for best fictional work written in English.

The book Forever … by Judy Blume was another book on the banned list. Ms. Blume has authored 26 books that range from children’s literature to young adult to adult fiction. In 2023, Time magazine named Blume one of the 100 most influential people in the world. The book Forever …, like several of Blume’s books, deals with issues such as masturbation, teen sex and birth control. Among Blume’s many accolades is recognition as a Library of Congress Living Legend, and winning the 2004 National Book Foundation medal for distinguished contributions to American letters.

Another banned book was What Girls are Made Of by Elana Arnold. That novel was a finalist for the 2017 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. Nine of Arnold’s books have been selections of the Junior Literary Guild. The poetry book Milk and Honey by Canadian author Rupi Kaur was another of the banned books. Kaur writes about experiences faced by Indian women and immigrants, and she includes descriptions of surviving sexual assault. Kaur’s book sold 3 million copies, and she has 3.5 million followers on Instagram. In 2017, both the BBC and Vogue included Kaur in their “women of the year” lists; and in 2019, The New Republic named her “Writer of the Decade.” The final author on the state of Utah banned books list is Craig Thompson for his graphic novel Blankets. Thompson is an American author who has been awarded four Harvey Awards, three Eisner Awards and two Ignatz Awards. Blankets was a 600-page autobiographical novel that won an award from Time magazine as the best graphic novel of 2003. Thompson’s gritty novel highlighted his disenchantment over his fundamentalist Christian upbringing.

It should be immediately apparent that all 13 of these banned books would pass the test of having “serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.” These criteria are part of the federal Miller test for determining whether a book could be published. This is why Utah bill HB29 defined the term “objective sensitive material.” Apparently, any appearance of sexual activity or masturbation is sufficient to meet this criterion. This test directly contravenes the federal three-part test for obscenity that included a determination of the artistic merit of the works in question. Of course, these bills were opposed by library associations across the state. Rebekah Cummings, the chair of the Utah Library Association, pointed out that before Utah bills HB374 and HB29, librarians used the “SLAP method” (i.e., serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value) to determine holistically whether books should be banned. If a book met the SLAP merits, uncomfortable situations in books such as assault or sexuality could provide support and relatability for readers. Cummings asked “Are they [school teachers or school librarians] going to uphold the federal law that says the work has to be taken as a whole or are they going to uphold state law that says if any of these things are in it, you have to pull the book?”

PEN America also strongly criticized the Utah bill and its consequences. Kasey Meehan, the Freedom to Read program director at PEN America, called this “A dark day for the freedom to read in Utah … The state’s No-Read List will impose a dystopian censorship regime across public schools and, in many cases, will directly contravene local preferences. Allowing just a handful of districts to make decisions for the whole state is antidemocratic, and we are concerned that implementation of the law will result in less diverse library shelves for all Utahns.” Critics of HB29 pointed out that both the Bible and the Quran, and possibly The Book of Mormon as well, would fail the state’s “objective sensitive material” test.

It is possible that Utah bill HB29 was designed to force the Supreme Court to re-visit guidelines for obscenity. Under normal circumstances, challenges to the Miller test would fail, as there is a significant history of legal decisions that have failed to overturn this test. However, it is uncertain how the current Supreme Court would view such a suit. Not only have the current justices seemed willing, even eager, to overturn prior precedent, but the court has also been willing to give extraordinary deference to arguments based on religious beliefs. In the meantime, we can expect to see many more books banned from all public school libraries in Utah.

The Recent Surge of School Library Book Bans:

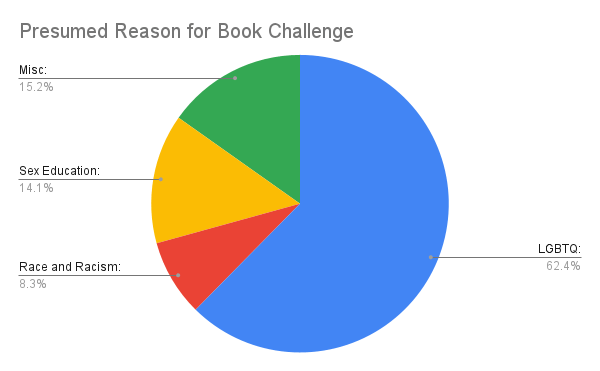

The ongoing surge in book bans in American school and public libraries largely bears on the question of who we are as Americans. It is mostly driven by a small number of conservative activists and politicians, who are reacting against myriad attempts by a number of minority groups and individuals to be included as important parts of American history and the American public. Its advertised goal, although seldom stated quite so bluntly, is to ensure that heterosexual, white Christian children are not made to feel “uncomfortable” by discussions of people not like them or of problems that they presumably do not share. For example, in 2021 a Republican Texas state legislator launched an investigation into 850 books that “might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex.” The categories of books he challenged are summarized in the pie chart of Fig. IV.1.

The surge is triggered in part as a response to recent scholarly attempts to expand the American narrative. In 2019 the New York Times sponsored an essay series known as the 1619 Project, which argued that slavery is such a central aspect of American history that the American story should be considered to have begun with the arrival of the first slave ship in 1619. The descendants of slaves on that and subsequent ships want to be included as a central part of the American narrative. In attempts to understand how racial inequality has persisted in society despite policies designed to eliminate it, critical race theory (CRT) has been introduced in some graduate programs in law and philosophy to consider the viewpoint that some racism is endemic in our customs and sometimes hidden in our laws.

Advances in research on brain development in human fetuses and infants have improved understanding of biological differences between sex and gender. Some social scientists have seized upon those developments to argue more broadly that gender is a social construct. And as we have discussed in our post on Sex and Gender, social pressures and sexual confusion have contributed to a rapid increase in teenagers who now identify as non-binary or trans. Those individuals, too, want to be included in the American story and treated with respect. And in the past decade, many schools and a number of companies have added offices of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) to install policies that welcome candidates from marginalized groups.

But that desire of marginalized groups to be included has also led to some clumsy censorship by left-leaning organizations. This includes the bans discussed above of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn because it used language common in the U.S. of its time. It includes a name change for a Children’s Literature Award to remove the honor from Little House on the Prairie author Laura Ingalls Wilder, because her work included what are now viewed as stereotypical depictions of Native Americans and people of color. It included a decision by Dr. Seuss Enterprises to cease publication of six children’s books by Dr. Seuss because they contained images now judged offensive.

These attempts at censorship to remove material considered offensive by marginalized groups were roundly criticized as “cancel culture” by groups on the political right. But now those right-wing groups have themselves seized the opportunity to raise the ante on cancel culture dramatically. A number of Republican-controlled state legislatures have passed new laws greatly restricting what topics, if any, on race history, sexuality or gender can be discussed in public schools, all the way up to some college classrooms. They have outlawed presentations of critical race theories (very loosely defined in those laws) in middle schools and high schools, where the subject had never actually been taught. New laws also restrict rights granted to self-identified transgender individuals and some outlaw medical treatment for gender dysphoria in teens and pre-teens. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis has signed laws that allow individual parents to demand the removal of works they deem objectionable from school libraries, despite the Supreme Court’s Island Trees Union ruling discussed in Part I of this post. All these efforts of the last few years – cumulatively characterized by Jonathan Friedman as an “Ed Scare” replacing the Red Scare of the Cold War — provide the framework in which we are seeing a dramatic upsurge in U.S. book bans.

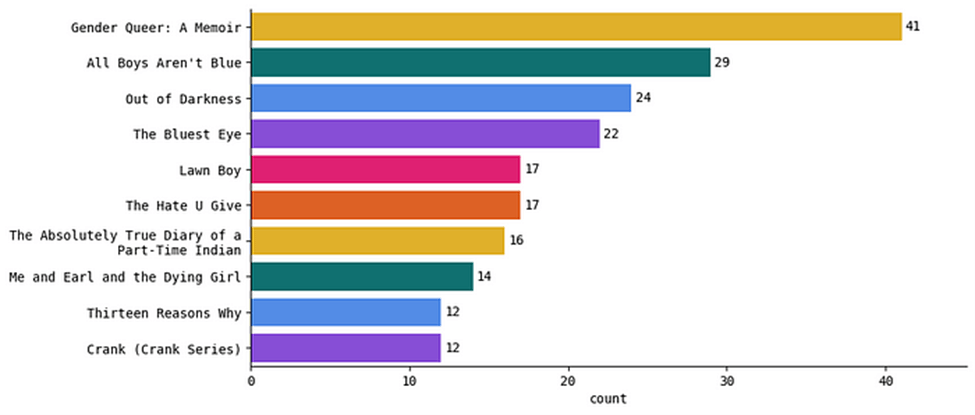

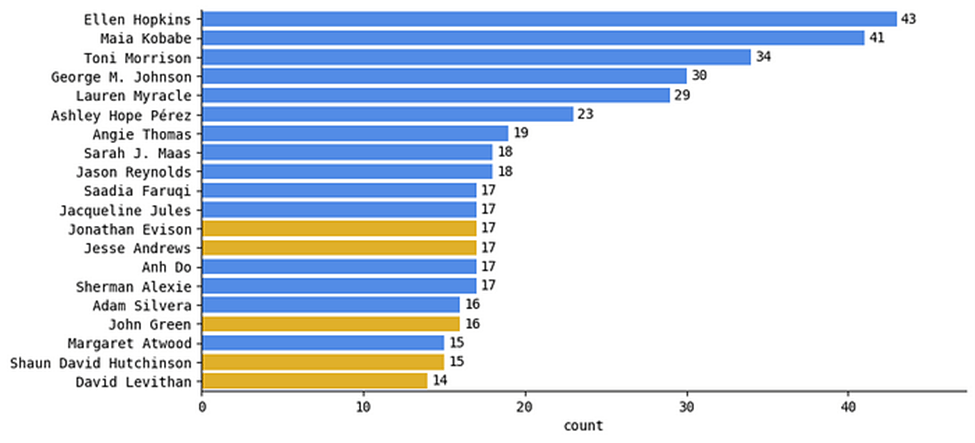

Yennie Jun has carried out a detailed analysis of U.S. school library and classroom book bans during a one-year period beginning on July 1, 2021, using PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans dataset. The dataset, which may not capture all bans during the period, includes 1,648 unique books written by 1,261 different authors. The distribution of bans among states was shown in Part I in the map of Fig. I.2. The ten books banned in the most school districts are shown in Fig. IV.2.

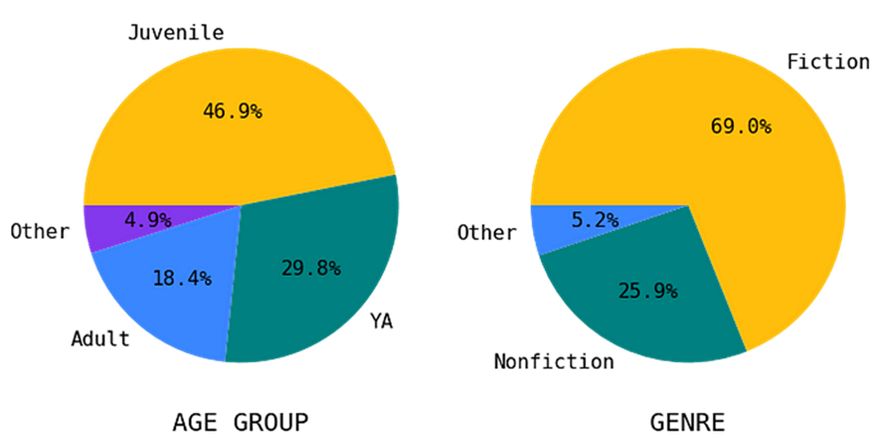

The banned books were mostly written after the year 2000 for juvenile and young adult audiences, as indicated in Fig. IV.3. Among banned books published before 2000 are Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and Beloved, Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel about the holocaust Maus, and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five.

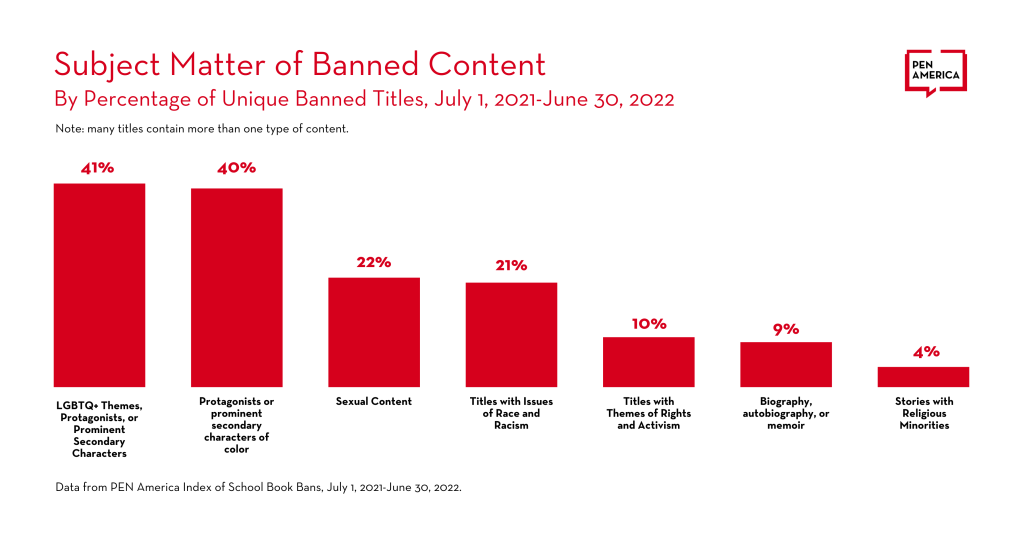

The common themes of the recent book bans and the most frequently banned authors are indicated in Figs. IV.4 and IV.5, respectively. 75% of the most banned authors identify as women, non-binary, or people of color. Frequently banned topics include: discussions of gender, sexuality and transgender experiences, or books featuring prominent LGBTQ characters; books about racism and Black history, including slavery, or just containing prominent characters of color; books about Muslim experiences in America; works on abortion and women in science and mathematics; books about activists’ fight for rights. These are the topics American conservatives do not want their children exposed to. The banned books are chosen to narrow education or exposure about topics that do not fit within an outdated conception of America as an exceptional, prim, white, male-dominated, Christian society, where women are not encouraged to explore non-traditional roles and deviations from traditional heterosexuality are to be kept silent.

The banned books are chosen to narrow education or exposure about topics that do not fit within an outdated conception of America as an exceptional, prim, white, male-dominated, Christian society, where women are not encouraged to explore non-traditional roles and deviations from traditional heterosexuality are to be kept silent.

The trends revealed in Figs. IV.3-5 have only increased in the year beginning on July 1, 2022. This is the heart of Republicans’ current “war against woke”: it is a war against inclusion and tolerance, and often against science. The political agenda seems desperate; in most of these cases, the horse has already left the barn. Demographic trends work against maintaining this outdated conception, except by (minority) government fiat or force.

The vast majority of American citizens (roughly 70% according to an American Library Association poll, see Fig. IV.6) do not support book bans. So how did we get here? Concerned parents certainly can recommend that their own children avoid particular books. But why should the few who object to specific library books, textbooks or curricula get to decide what the many get taught in public schools? Just as we revealed, in our discussion of texts about evolution in Section II, that attempts to censor and eliminate various textbooks in Texas schools in the late 20th century were driven by a single, fundamentalist Christian couple, it turns out that the attempts to suppress critical race theory, and the drive to pass legislation in states to restrict what can be taught there, are to a considerable degree the work of a single person.

V. The instigator: christopher rufo

The recent proliferation of state laws limiting what can be taught in public schools, forbidding certain topics from being discussed in K-12 classes, and encouraging citizen efforts to ban certain books in schools and libraries, represents an organized attempt by the Republican Party to capitalize on divisive social issues. A common theme in laws that have been pushed through state legislatures is a prohibition on teaching ‘critical race theory’ in middle schools and high schools. Critical race theory involves the notion that race relations and racism are endemic in many of our laws and customs. It sprang from an attempt to understand how racial inequality in society persisted despite policies designed to eliminate it. As it involves postmodernist philosophy and is rather abstruse, it is not taught in K-12 schools and is generally restricted to graduate programs in law and philosophy. So, why do conservatives believe that critical race theory is widely taught in our public schools, that it “has pervaded every aspect of the federal government,” and poses “an existential threat to the United States”?

It turns out that the above statements about critical race theory, and the drive to pass legislation in states to restrict what can be taught there, are to a considerable degree the work of a single person. Christopher Rufo (Fig. V.1) is a conservative activist. He is currently a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. Before that, he was a fellow at the Discovery Institute; as we have discussed in our blog post on evolution, the Discovery Institute is an organization that promotes the unscientific Intelligent Design hypothesis, as an alternative to the current scientific consensus on evolutionary theory. Earlier still, Rufo was a member of the Claremont Institute (where he worked with the notorious James O’Keefe of Project Veritas), the Heritage Foundation, and the ironically named Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism. The quote in the preceding paragraph are from Rufo.

Rufo has been quite candid about his goals. He wants funding for public schools to be replaced by ‘universal school choice,’ that is, funds for K-12 education should be provided to all parents who are then free to use those funds for private school tuition. And Rufo has described his methods as “To get to universal school choice, you need to operate from a premise of universal public school distrust.” Thus, Rufo’s mission is to stoke distrust of public schools among Americans. This particular agenda has been taken up by Republican parties across the U.S.

Rufo has described his strategy as follows: “We will eventually turn [critical race theory] toxic, as we put all of the ‘various cultural insanities’ under this brand category. The goal is to have the public read something ‘crazy’ in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory.’” Rufo’s aim is to generate rage among right-wing white Christians, and to translate that rage into legislation to limit and proscribe what teachers can present in the classroom. In his appearances on Fox News and other right-wing programs, Rufo made accusations about programs in diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), which have become very popular at universities and corporations. He invited listeners to leak documents to him that would demonstrate that such programs constitute an attack on straight white citizens.

Rufo received a large number of documents from his listeners. He turned these into provocative sound bites that attempted to cast DEI initiatives as frontal assaults on patriotic white Americans. Some of the situations mentioned by Rufo refer to actual instances where DEI coordinators accused white Americans of systemic racism, or of perpetuating a system of white dominance that needed to be challenged. Such claims feed directly into the sense that conservative white males have, that they are under attack from ‘woke’ leftists who threaten their way of life. These sentiments are widely disseminated through right-wing media and Fox News. So video or print descriptions of a few DEI advocates suggesting that all whites are racist, or that ‘white privilege’ needs to be attacked, have certainly helped to heighten the sense of outrage among white conservatives.

However, Rufo’s attempt was to discredit the entire push for a heightened awareness of diversity issues in our society. In this respect, Rufo has shown himself to be perfectly willing to summarize the views of his antagonists in ways that dramatically mis-state their intentions. Here are a few examples.

- Rufo accused Los Angeles public school teacher R. Tolteka Cuauhtin of pressuring his students to honor the Aztec practices of human sacrifice and cannibalism; and the teacher urged his students to commit “countergenocide” against white Christians. This story was amplified by right-wing journalists Rod Dreher and Fox News’ Laura Ingraham. Cuauhtin responded that Rufo had spread “classically racist interpretations about indigenous cultures, fabricated lies about mass human sacrifice.” Cuauhtin also claimed that Rufo never contacted him regarding the story he issued. He only realized this when he began getting death threats from angry citizens.

- Rufo claimed that a diversity consultant for the Treasury Department had “told employees essentially that America was a fundamentally white supremacist country,” and he urged them to “accept their white racial superiority.” But the diversity consultant did not say that.

- Rufo claimed that a document from an Oregon school district advocated principles of a Brazilian Marxist Paulo Freire, and espoused turning students into “liberated masses” who would fight against the “Marxist revolution’s enemies.” In fact, the document only cited Freire’s advocacy for treating education as an act of liberation and mutual humanization.

- In an article for Hillsdale College’s Imprimis magazine, Rufo accused Prof. Cheryl Harris of UCLA Law School of calling for “suspending private property rights, seizing land and wealth and redistributing them along racial lines.” Prof. Harris responded that “I’ve never said such a thing.” She responded that “It’s difficult to start out a discussion of what [critical race theory] is when what is being projected really bears no resemblance to it and has no intention of bearing any resemblance to it.”

Rufo’s allegations were widely reported by right-wing media. On Fox News, he made regular appearances on shows with pundits such as Tucker Carlson and Laura Ingraham. After an appeal by Rufo, in 2017 President Donald Trump issued an executive order “prohibiting federal agencies from having diversity training that addressed topics like systemic racism, white privilege and critical race theory.” Trump’s executive order was subsequently revoked by President Biden.

In addition to his demonization of critical race theory, Rufo has been a strong proponent of legislative bans on teachers discussing LGBTQ issues in the classroom. He has been particularly visible in Florida, where he has forged a strong alliance with Governor Ron DeSantis. He has proceeded in much the same way as his attacks on DEI measures. In January 2022 Rufo urged people to leak to him “documents, PDFs, audio-video and training materials related to gender, grooming and trans ideology in schools.”

Here, Rufo is again pursuing his goal of making the public distrust our public schools. He is trying to create antagonism between parents of schoolchildren and teachers and librarians. Rufo is specifically aiming at discussions of sex and gender in our schools, with emphasis on LGBTQ issues and with a specific focus on transgender youth. Rufo’s critics claim that his attacks “represent a new era of moral panic, one with echoes from decades ago that gay teachers were a threat to children.” For example, Rufo maintains that public schools are “often hunting grounds for sexual predators.” Ron DeSantis’ press secretary has claimed that opponents to Florida’s new “Don’t Say Gay” law, which restricts discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity issues in public schools, are themselves ‘groomers’ – adults who are sexually pursuing children.

Christopher Rufo has also been deeply involved in the ongoing dispute between Ron DeSantis and the Walt Disney Company. To support his declaration of “moral war” against Disney, Rufo aired a video of an internal Disney meeting where a producer mentioned the addition of “’queerness’ to an animated series and mentioned, tongue in cheek, her ‘not-at-all-secret gay agenda.’” Rufo also posted an article where he showed mug shots of Disney employees who had been charged with child sexual abuse. In Rufo’s article, he neglected to say that none of the sexual abuse incidents had occurred at Disney parks. Nor did he mention a rejoinder from Disney that the number of people arrested constituted “one one-hundredth of one percent of the 300,000 people we have employed during this time period.”

It remains to be seen whether DeSantis’ attacks on the highly popular Disney Company are a politically savvy move or a serious miscalculation, threatening billions of dollars of corporate investment and many thousands of jobs in Florida. However, on the issues of DEI initiatives and LBGTQ and gender issues, Rufo has been very effective. In the state of Virginia race for Governor in Fall 2021, a major reason for the surprising election of Glenn Youngkin over Terry McAuliffe came in a debate when McAuliffe said “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach.” This unfortunate statement galvanized right-wing attacks on progressive school boards and became a rallying cry for conservative voters. Groups like Moms for Liberty and other right-wing parent activist organizations have sprung up across the country. The book banning efforts we described in Section IV form a major thrust of these groups. Their efforts have sometimes been successful, while in other instances they have been blocked by coalitions of parents who support their teachers and librarians. However, a spate of state laws have been passed in the past couple of years which could have a serious effect on subjects that are taught in K-12 classes, or even discussed by teachers in public schools.

VI. are book bans effective?

History demonstrates that book bans are not typically effective. As we noted earlier, works by Copernicus, Galileo and Darwin only grew in importance after their banning, and came to dominate scientific thought. Furthermore, the act of banning tends to arouse curiosity in the public denied access, and the popularity of banned books often surges in the wake of a ban. This is especially true of young people, who often revel in the opportunity to break cultural taboos. This was seen, for example, in the second half of the 20th century, when bans of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita led to enormous popularity of both these particular books and other works by the same authors. All three authors became literary celebrities. In 1998 the Modern Library ranked Portnoy’s Complaint 52nd on its list of the hundred best English-language novels of the 20th century. Lolita is now joined among the best known banned-books-turned-classics by John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, James Joyce’s Ulysses, and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five.

A few examples from the recent spate of U.S. book bans amplify this point. Within a week of its banning by a Tennessee school board in early 2022, Art Spiegelman’s decades-old, Pulitzer-Prize-winning graphic novels Maus (see Fig. VI.1), about his father’s experiences as a holocaust survivor, surged to second place in Amazon’s overall list of best-selling books, when it hadn’t been among the top 1000 books before the ban. When concerns over racist imagery led to six Dr. Seuss books being withdrawn (by Dr. Seuss Enterprises) from circulation, booksellers saw a dramatic, instantaneous surge in demand for many other Dr. Seuss titles.

The most often banned book in U.S. libraries in 2021, according to the American Library Association, was Gender Queer, a graphic memoir by asexual and non-binary artist Maia Kobabe. The publicity from all those bans has led to skyrocketing sales of Gender Queer, producing multiple printings and a new hardcover edition. Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman’s soaring poem The Hills We Climb, recited by her to great reception at Joe Biden’s 2021 Presidential Inauguration, was recently placed on restricted access at a Miami-Dade County school in Florida, when a single parent complained that it contained indirect hate messages (apparent only to that parent). In the wake of that ban, all of Gorman’s books have now skyrocketed in sales.

However, authors have been quick to point out that book bans do not sell books in general. Many banned books gradually disappear, while a few see sales spikes. However, this experience is not so different from that for unbanned books, where only a select few gather the publicity, reviews, and word-of-mouth support to become bestsellers.

While book bans have always had questionable effectiveness, they seem to be downright folly in the internet and artificial intelligence age. Students whose curiosity is aroused by book bans can ask AI chatbots for summaries of the banned books. They can find some of the material, along with far more questionable material, online. They can find banned books easily available on Amazon. PEN America hosts a Banned Books Week every year to celebrate and encourage reading of many banned books. Thus, the main impact of book bans from school and public libraries is to complement word-of-mouth in alerting young people to what they should be reading now. Furthermore, some curious teens may question why their would-be protectors from sexual groomers nonetheless support a candidate for President who was found liable for sexual abuse by a jury of his peers. The bans are often counterproductive on their intended audience.

Thus, the main impact of book bans from school and public libraries is to complement word-of-mouth in alerting young people to what they should be reading now.

Furthermore, allowing individual parents the right to demand removal of selected books from school libraries can easily backfire against Christian conservatives. Consider the recent satirical piece Smutty Books Have No Place in Our Schools. It’s Time to Ban the Bible. Authors Kathryn and Katrina Baecht make the following not-so-outlandish points: “Ever since the school started promoting Bible study, it’s been nonstop questions from our nine-year-old. ‘Daddy, what’s a harlot?’ ‘Daddy, what’s ‘spilling your seed’?’ ‘Daddy, in order to repopulate the earth after the flood, wouldn’t Noah’s family have to commit at least cousin-level incest?’…[The Bible] starts with the story of two slackers walking around naked and taking suggestions from Satan about fruit. It’s downhill from there…[Later] A young Bernie Sanders-type guy goes around feeding the poor and spreading communist propaganda about how there are enough loaves and fishes to feed everybody… Members of the school board, the state of Texas may call the Bible the ‘Good Book,’ but I call it ‘liberal smut.’ If anyone’s going to talk to my kids about incest, seed spilling, or how to identify acceptable fruit, it’s going to be me. So, let’s do the Christian thing and ban this godforsaken book.” Flimsier excuses have been used in many of the recent bans.

It is fine for parents to advise their own children against reading certain books; that is their prerogative. But why should they have the right to impose those bans on other families who don’t support them? It seems there are only a few motivations for calling for book bans today. Some parents may hope to signal their own virtue by doing so. But organized right-wing groups are aiming for a two-track education system, where students receive instruction on two very different narratives concerning the American story. As we pointed out in Section V, another motivation is to provide conservatives with ammunition to fuel their outrage through claims that left-wing “radicals” are attempting to force conservative parents to accept ideas that they find abhorrent (such as claims that racial bias exists or has existed in the past, that LGBTQ+ groups deserve acceptance and tolerance, and that the beliefs of non-Christian groups should be tolerated on the same level as Christian beliefs).

Book bans are effective only within the context of fascism, when there is tight control on all information, when the bans are broad, and violations are subject to extreme punishment. But in the history of human civilizations, fascism does not itself last for long. Citizens eventually rebel against government constraints they find too tight or unreasonable, often with leadership from young rebels. Book bans and book burning are one symptom of desperation to hold onto power.

references:

American Library Association, 2022 Book Ban Data, https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/book-ban-data

J. Friedman and N.F. Johnson, Banned in the U.S.A.: The Growing Movement to Censor Books in Schools, https://pen.org/report/banned-usa-growing-movement-to-censor-books-in-schools/

Freedom to Read, Bannings and Burnings in History, https://www.freedomtoread.ca/resources/bannings-and-burnings-in-history/

Spark Press, The History of Banned Books, https://gosparkpress.com/the-history-of-banned-books/

Banned Books: The History of Banned Books, https://libguides.pima.edu/bannedbooks/history

B. Blakemore, The History of Book Bans – And Their Changing Targets – in the U.S., National Geographic, April 24, 2023, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/history-of-book-bans-in-the-united-states?loggedin=true&rnd=1683057817913

A. Brady, The History (and Present) of Banning Books in America, https://lithub.com/the-history-and-present-of-banning-books-in-america/

H.J. Graff, The History of Book Banning, https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/columns-and-blogs/soapbox/article/88195-harvey-j-graff-examines-the-history-of-book-banning.html

Wikipedia, List of Books Banned by Governments, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_books_banned_by_governments

C. Grady, How the New Banned Books Panic Fits Into America’s History of School Censorship, Vox, Feb. 17, 2022, https://www.vox.com/culture/22918344/banned-books-history-maus-school-censorship-texas-harold-rugg-beloved-huck-finn-dr-seuss

J. Mathis, A History of Book Banning in America, The Week, Sept. 22, 2022, https://theweek.com/briefing/1016831/us-book-banning

Starting Point: Banned Books of the Scientific Revolution, https://shareok.org/bitstream/handle/11244/47154/SP-Banned-books.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y

Wikipedia, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncle_Tom%27s_Cabin

K.L. Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture (University Press of Florida, 2019), https://upf.com/book.asp?id=9780813064130

Wikipedia, Lost Cause of the Confederacy, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lost_Cause_of_the_Confederacy

Wikipedia, Comstock Laws, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comstock_laws

L. Vander Ploeg and P. Belluck, What to Know about the Comstock Act, New York Times, May 16, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/16/us/comstock-act-1978-abortion-pill.html

Wikipedia, Deutsche Physik, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deutsche_Physik

Wikipedia, Fahrenheit 451, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fahrenheit_451

Wikipedia, McCarthyism, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/McCarthyism

Wikipedia, A Canticle for Leibowitz, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Canticle_for_Leibowitz

Wikipedia, The Book Thief, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Book_Thief

A. Gratz, Ban This Book (Tom Doherty Associates, 2017), https://www.alangratz.com/writing/ban-this-book/

Wikipedia, Reading Lolita in Tehran, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reading_Lolita_in_Tehran

Britannica, Ptolemaic System, https://www.britannica.com/science/Ptolemaic-system

Wikipedia, Nicolaus Copernicus, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicolaus_Copernicus

Wikipedia, On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_revolutionibus_orbium_coelestium

Wikipedia, Inquisition, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inquisition

Wikipedia, Index of Forbidden Books, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Index_Librorum_Prohibitorum

Wikipedia, Sidereus Nuncius, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sidereus_Nuncius

Wikipedia, Aether (Classical Element), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aether_(classical_element)

A. Rein, Banned Books Week: Galileo’s Dialogue, American Institute of Physics, Sept. 24, 2018, https://www.aip.org/history-programs/niels-bohr-library/ex-libris-universum/banned-books-week-galileo%E2%80%99s-dialogue

Wikipedia, Galileo Affair, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galileo_affair

J. Mianecki, 378 Years Ago Today: Galileo Forced to Recant, Smithsonian Magazine, June 22, 2011, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/378-years-ago-today-galileo-forced-to-recant-18323485/

DebunkingDenial, Evolution, Part I: Concepts and Controversy, https://debunkingdenial.com/evolution-part-i-concepts-and-controversy/

Wikipedia, On the Origin of Species, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_the_Origin_of_Species

Wikipedia, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Descent_of_Man,_and_Selection_in_Relation_to_Sex

Wikipedia, Evolution and the Catholic Church, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolution_and_the_Catholic_Church

Wikipedia, Humani Generis, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humani_generis

Wikipedia, Of Pandas and People, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Of_Pandas_and_People

U.S. Supreme Court case, Edwards v. Aguillard (1987), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/482/578/

Wikipedia, Foundation for Thought and Ethics, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foundation_for_Thought_and_Ethics

Wikipedia, Institute for Creation Research, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Institute_for_Creation_Research

Wikipedia, Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kitzmiller_v._Dover_Area_School_District

National Center for Science Education, Censorship of Evolution in Texas, Creation/Evolution Journal 3 (1982), https://ncse.ngo/censorship-evolution-texas

A. Bridgman, Texas Board Votes to Change Rule on Texts’ Treatment of Evolution, April 25, 1984, https://www.edweek.org/education/texas-board-votes-to-change-rule-on-textstreatment-of-evolution/1984/04

The U.S. Constitution Doesn’t Establish a Christian Nation, https://presidentialsystem.org/2019/06/28/the-u-s-constitution-doesnt-establish-a-christian-nation/

J.R. Vile, Christian Amendment, The First Amendment Encyclopedia, https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1037/christian-amendment

Wikipedia, The Rabbit’s Wedding, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Rabbits%27_Wedding

Wikipedia, Girolamo Savonarola, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Girolamo_Savonarola

Wikipedia, Roth v. United States, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roth_v._United_States

U.S. Supreme Court Case, John F. TINKER and Mary Beth Tinker, Minors, etc., et al., Petitioners, v. DES MOINES INDEPENDENT COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT et al., https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/393/503

U.S. Supreme Court Case, BOARD OF EDUCATION, ISLAND TREES UNION FREE SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 26 et al., Petitioners, v. Steven A. PICO, by his next friend Frances Pico et al., https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/457/853

American Library Association, 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books: 1990-1999, https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/decade1999

American Library Association, Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books: 2000-2009, https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/decade2009

American Library Association, Top 100 Most Banned and Challenged Books: 2010-2019, https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/decade2019

Why Do People Think Huck Finn is Racist?, PBS, Sept. 23, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/video/why-do-people-think-huck-finn-is-racist-0rhbwg/

M. Farkus, Banned Books: ‘The Catcher in the Rye’, The Simmons Voice, Sept. 27, 2017, https://simmonsvoice.com/8495/2017-2018/banned-books-the-catcher-in-the-rye/

P. Radulovic, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark’s Legacy of Library Challenges and Bans, Polygon, Aug. 14, 2019, https://www.polygon.com/2019/8/14/20804222/scary-stories-to-tell-in-the-dark-banned-books

Marshall Libraries, Banned Books 2020 – Harry Potter Series, https://www.marshall.edu/library/bannedbooks/harry-potter-series/

S. Lee, Lauren Myracle: Her Novels Are Beloved – And Banned, Entertainment, Nov. 4, 2011, https://ew.com/article/2011/11/04/lauren-myracle-her-novels-are-beloved-and-banned/

P. Engel, Why ‘Captain Underpants’ is the Most Banned Book in America, Business Insider, Sept. 26, 2013, https://www.businessinsider.com/why-captain-underpants-is-the-most-banned-book-in-america-2013-9

C. Collins, Top Ten Banned Book: Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, American Library Association, April 28, 2022, https://www.oif.ala.org/top-ten-banned-book-absolutely-true-diary-of-a-part-time-indian/

A. Clark, Critics Hate Grey. So Why Can’t Readers Get Enough of the Dark Side of Fifty Shades?, The Guardian, June 27, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jun/28/what-el-james-grey-success-tells-us-about-future-of-fiction

N. Ford, Book Banning and Romance Fiction in the United States, https://sites.duke.edu/unsuitable/book-banning/

American School of Madrid, Challenged/Banned/Retrained: Of Mice and Men, https://asmadrid.libguides.com/c.php?g=679335&p=4841647

B. Chappell, A Texas Lawmaker is Targeting 850 Books That He Says Could Make Students Feel Uneasy, NPR, Oct. 28, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/10/28/1050013664/texas-lawmaker-matt-krause-launches-inquiry-into-850-books

The 1619 Project, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html

S. Sawchuk, What Is Critical Race Theory, and Why Is It Under Attack?, Education Week, May 18, 2021, https://www.edweek.org/leadership/what-is-critical-race-theory-and-why-is-it-under-attack/2021/05

DebunkingDenial, Sex, Gender, Genome, and Hormones, https://debunkingdenial.com/sex-gender-genome-and-hormones-part-i/

K. Chow, Little House on the Controversy: Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Name Removed from Book Award, NPR, June 25, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/06/25/623184440/little-house-on-the-controversy-laura-ingalls-wilders-name-removed-from-book

C. Grady, Dr. Seuss Is a Beloved Icon Who Also Drew Some Extremely Racist Stuff, Vox, Mar. 3, 2021, https://www.vox.com/culture/22309286/dr-seuss-controversy-read-across-america-racism-if-i-ran-the-zoo-mulberry-street-mcgelliots-pool

J. Friedman, Goodbye Red Scare, Hello Ed Scare, Inside Higher Ed, Feb. 23, 2022, https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2022/02/24/higher-ed-must-act-against-educational-gag-orders-opinion

Y. Jun, The Forbidden Pages: A Data Analysis of Book Bans in the U.S., Towards Data Science, Mar. 6, 2023, https://towardsdatascience.com/the-forbidden-pages-a-data-analysis-of-book-bans-in-the-us-e03a22fb0fa8

K. Meehan and J. Friedman, Banned in the USA: State Laws Supercharge Book Suppression in Schools, PEN America, April 20, 2023, https://pen.org/report/banned-in-the-usa-state-laws-supercharge-book-suppression-in-schools/

American Library Association, Large Majorities of Voters Oppose Book Bans and Have Confidence in Libraries, Mar. 24, 2022, https://www.ala.org/news/press-releases/2022/03/large-majorities-voters-oppose-book-bans-and-have-confidence-libraries

Wikipedia, Christopher Rufo, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Rufo

Wikipedia, Project Veritas, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Veritas

S. Jones, How to Manufacture a Moral Panic, New York Magazine, July 11, 2021, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2021/07/christopher-rufo-and-the-critical-race-theory-moral-panic.html

L. Meckler and J. Dawsey, Republicans, Spurred By an Unlikely Figure, See Political Promise in Targeting Critical Race Theory, Washington Post, June 21, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2021/06/19/critical-race-theory-rufo-republicans/

K. Drum, At Fox News, It’s Always About Scary Threats to White People, Mother Jones, Jan. 8, 2021, https://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2021/01/at-fox-news-its-always-about-scary-threats-to-white-people/

T. Gabriel, He Fuels the Right’s Cultural Fires (and Spreads Them to Florida), New York Times, April 24, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/24/us/politics/christopher-rufo-crt-lgbtq-florida.html

Wikipedia, Florida Parental Rights in Education Act, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florida_Parental_Rights_in_Education_Act

K. Tumulty, McCauliffe Ended Up Dancing to Youngkin’s Choreography, Washington Post, Nov. 3, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/11/03/mcauliffe-ended-up-dancing-youngkins-choreography/

Wikipedia, Moms for Liberty, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moms_for_Liberty

Wikipedia, The Catcher in the Rye, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Catcher_in_the_Rye

Wikipedia, Portnoy’s Complaint, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portnoy%27s_Complaint

Wikipedia, Maus, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maus

S. Kasakove, The Fight Over ‘Maus’ Is Part of a Bigger Cultural Battle in Tennessee, New York Times, Mar. 4, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/04/us/maus-banned-books-tennessee.html

L. Brown, Holocaust Book ‘Maus’ Sales Soar After School Board Ban, New York Post, Jan. 31, 2022, https://nypost.com/2022/01/31/holocaust-book-maus-sees-sales-soar-after-school-board-ban/

L. Brown, Dr. Seuss Decision Followed Lengthy Study of Racist Themes in His Books, New York Post, Mar. 2, 2021, https://nypost.com/2021/03/02/decision-to-pull-dr-seuss-books-followed-study-accusing-author-of-racism/

S. Prager, While Some Banned Queer Books See a Sales Bump, Others Quietly Disappear, NBC News, Feb. 22, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-news/banned-queer-books-see-sales-bump-others-quietly-disappear-rcna16859

https://www.theamandagorman.com/

S. Barnes, Who Is Amanda Gorman? Learn More About the Young Poet Laureate Who Stole the Show with Her Inauguration Poem, My Modern Met, Jan. 21, 2021, https://mymodernmet.com/amanda-gorman-inaugural-poet/

S. Barnes, Amanda Gorman’s Book Sales Skyrocket Following a Ban on Her Poem in a Florida School, My Modern Met, June 6, 2023, https://mymodernmet.com/amanda-gorman-banned-books/

A. Karre, No, Actually, Book Bans Don’t Sell Books, AZMirror, April 21, 2022, https://www.azmirror.com/2022/04/21/no-actually-book-bans-dont-sell-books/

Amazon, Banned Books List 2023, https://www.amazon.com/s?k=banned+books+list+2023&i=stripbooks&crid=2L9860UBHNBNL&sprefix=bann%2Cstripbooks%2C141&ref=nb_sb_ss_ts-doa-p_1_4

PEN America, Banned Books Week 2022, https://pen.org/campaign/banned-books-week-2022/

K. Baecht and K. Baecht, Smutty Books Have No Place in Our Schools. It’s Time to Ban the Bible, McSweeney’s, April 25, 2023, https://www.mcsweeneys.net/articles/smutty-books-have-no-place-in-our-schools-its-time-to-ban-the-bible