June 21, 2023

I. Introduction

The last two years have seen the latest in a long historical series of surges in the banning of books in the U.S. (see Fig. I.1). This time, it’s Republican state legislatures in combination with a handful of conservative parents and parent groups that have banned school, and sometimes public, library books that deal with the latest right-wing “bogeyman” topics. Because book bans are often a form of intellectual denialism, it fits well within the theme of this blog site to dig into this trend.

According to PEN America, from July 2021 through June 2022 they have recorded in U.S. school libraries “2,532 instances of individual books being banned, affecting 1,648 unique book titles…by 1,261 different authors.” The states involved in those bans are shown in the map of Fig. I.2. While the bans are dominated by Texas and Florida, whose Republican governors have both appeared to want their party’s nomination for the 2024 Presidential election, there have also been several hundred bans apiece in Tennessee and Pennsylvania. The schools affected by these bans have a combined enrollment of nearly 4 million students. And as seen in Fig. I.1, the trend seems to be still increasing.

Before getting into the subjects and reasons for the recent U.S. book ban surge, we will review some of the history of book bans worldwide. Book bans and book burning have been around pretty much as long as books themselves. A chronology of the major book bans and burnings in recorded history is given here; we will briefly mention only a few of these incidents in this section, but will deal with particular incidents in more detail in subsequent sections.

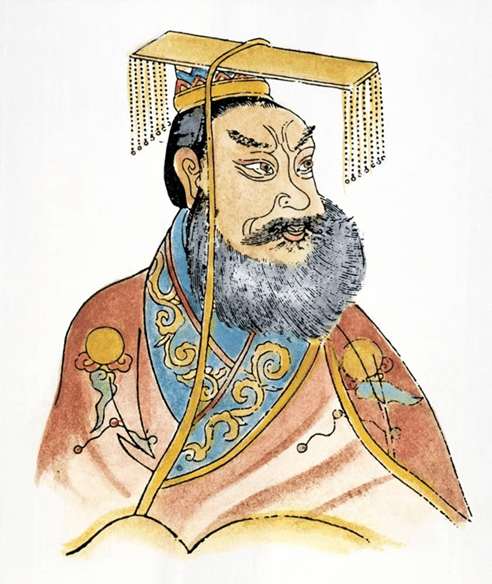

In the third century B.C.E., “the Chinese emperor Shih Huang Ti is said to have buried alive 460 Confucian scholars to control the writing of history in his time. In 212 B.C., he burned all the books in his kingdom, retaining only a single copy of each for the Royal Library—and those were destroyed before his death. With all previous historical records destroyed, he thought history could be said to begin with him.”

In 640 A.D., the Islamic caliph Omar reportedly “burned all 200,000 volumes in the library at Alexandria in Egypt. In doing so, he said: ‘If these writings of the Greeks agree with the Book of God they are useless and need not be preserved; if they disagree, they are pernicious and ought to be destroyed.” Much later, the Catholic Church in Europe banned two of the most important science books ever written: Copernicus’ On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres (1543) and Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), two books that established that the Earth orbits the Sun and not vice-versa. Galileo was famously imprisoned for the rest of his life for his “heresy” and forced to renounce his scientific arguments under threat of torture. Multiple bans affected Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), which established Darwin’s evidence that diverse species evolved from common ancestry via natural selection, favoring those species that were able within their environments to produce the most surviving offspring. Darwin’s fundamental book was banned from the library of Trinity College, Cambridge, where Darwin had been a student, in the late 19th century and was later banned by Yugoslavia, Greece, and the state of Tennessee during the middle of the 20th century.The “sin” of these important science books was providing evidence of phenomena in opposition to a literal interpretation of biblical accounts.

Many book bans (including the recent surge in the U.S.) have served causes of intolerance. In Nazi Germany in 1933, the government-led promotion of Aryan supremacy led to a series of massive bonfires in 34 cities across Germany to destroy “corrupt” and “degenerate” books (see Fig. I.4). It is estimated that as many as 80,000 – 90,000 books may have been burned in these ceremonies, including “thousands of books written by Jews, communists, and others. Included were the works of John Dos Passos, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Ernest Hemingway, Helen Keller, Lenin, Jack London, Thomas Mann, Karl Marx, Erich Maria Remarque, Upton Sinclair, Stalin, and Leon Trotsky.” One of the authors whose books were burned was the German poet Heinrich Heine. An 1820 play by Heine included the prophetic phrase: “Where they burn books, they will, in the end, also burn people.”

Book bans in America began long before the establishment of the United States. Later, in the leadup to and during the U.S. Civil War, the southern states banned many books exposing the evils of slavery, including Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851). Meanwhile, “Union authorities banned pro-Southern literature like John Esten Cook’s biography of Stonewall Jackson.” During the long aftermath of the Civil War there were many attempts in southern states to ban textbooks that described the war as one fought over slavery, as something less than the noble “Lost Cause” of the southerners’ preferred narrative. Following the adoption of the Comstock Act by the U.S. Congress in 1873 there was a century of bans affecting books about sexuality or birth control, and later fictional works accused of obscenity.

What even this small sampling of historical book bannings makes clear is that, generally speaking, book bans are an implicit recognition by groups in power (religious institutions, governments, even parents or groups of parents, etc.) that the seeds of their loss of power have been planted. The bans are acts of desperation, attempts either to hold back the tide of history and the advancement of human knowledge, or to regain the upper hand in an ongoing competition of ideas, or to impose on the masses concepts of morality held by the few.

…book bans are an implicit recognition by groups in power (religious institutions, governments, even parents or groups of parents, etc.) that the seeds of their loss of power have been planted. The bans are acts of desperation, attempts either to hold back the tide of history and the advancement of human knowledge, or to regain the upper hand in an ongoing competition of ideas, or to impose on the masses concepts of morality held by the few.

And they seldom succeed in the long run. History is not viewed as beginning with Shih Huang Ti. Works of the Greeks have long outlasted memory of caliph Omar. The scientific revolutions launched by Copernicus, Galileo, and Darwin have become foundations of modern scientific understanding of our universe and our planet. The “Jewish” books burned by the Nazis have long outlived the Nazi regime, and Einstein’s “Jüdische Physik” of Relativity has become the foundation of our modern understanding of the cosmos. The Lost Cause narrative has never taken root outside the American South, birth control has transformed the lives of women and families, and books once thought of as obscene have proliferated, not to mention far more controversial sexual material available on the internet. Indeed, book bans themselves are usually a “lost cause.”

Freedom of speech is not absolute. Consequently, there are conditions under which the banning of particular books may be justified. Among justifiable examples are books presenting: fraudulent claims; military or intelligence secrets without authorization; willful dissemination of disinformation or defamation; material intended to inspire insurrection against a duly elected government; or child pornography. But such cases cumulatively represent only a tiny fraction of all the book bans that have been enacted throughout history. Most books get banned because they present inconvenient truths or arguments.

Book bans in literature:

Since book bans so directly impact authors, it is not surprising that the subject has been central in a number of fictional works. Most famously, there is Fahrenheit 451 (see Fig. I.5), Ray Bradbury’s science fiction novel that imagines a future in which all books have been condemned as sources of confusion complicating people’s lives. Firemen have been reassigned to burn books and houses that harbor them. The protagonist of the novel is the fireman Guy Montag, who becomes disillusioned with his role, quits his job, and commits himself to the preservation of literary and cultural texts. While Bradbury’s original motivation for the book seems to have been triggered by the 1950s Joseph McCarthy hearings and blacklisting of Hollywood screenwriters and directors, in his later life Bradbury came to view “political correctness” as the effective censorship threat akin to book burnings. Fahrenheit 451 itself, despite critical success, numerous awards, and wide popularity, was banned and burned in apartheid South Africa and banned or censored in a number of U.S. schools.

Another science fiction novel, A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr., imagines a post-apocalyptic Dark Ages, called the “Simplification,” in which survivors of a global nuclear war turn violently against advanced knowledge and technology. During the multiple centuries of the Simplification, rampaging mobs of Simpletons destroy books en masse and attack and kill anyone with learning or the ability to read. The book centers on a monastery in the Utah desert, established by the war survivor Jewish engineer Isaac Leibowitz as a sanctuary to hide and preserve the collected writings and artifacts of 20th-century civilization, in the hope that they will help future generations eventually to rebuild with the aid of long-forgotten science. With the aid of these preserved texts, a new Renaissance begins by the year 3174. By 3781 a new age of high technology, similar to our own, has arisen and a new nuclear war begins, to complete a full cycle of cyclical history.

There are also two popular young adult novels that prominently feature book bans. In The Book Thief, by Australian Markus Zusak, pre-teen Liesel Meminger steals books that the German Nazis are threatening to destroy during World War II. Liesel survives bombings, but loses her own manuscript documenting her story, along with her foster family, which had been harboring a Jewish man. Many years later, as Liesel is dying as an old woman, Death returns to her the manuscript she lost in the bombing. In Ban This Book, by Alan Gratz, young Amy Anne Ollinger is angered by the banning of her favorite book from her school’s library. So she fights back by starting a secret banned book library out of her school locker, and finds herself embroiled in a battle with adults over censorship and book banning.

The importance of banned literature in guiding oppressed lives is highlighted in the 2003 non-fiction memoir Reading Lolita in Tehran, by Iranian professor of English Azar Nafisi. After her expulsion by the Islamic Republic from her university and her resignation from teaching, Nafisi formed a small book club with seven of her female students to read and discuss works of western literature that had been banned by the Islamic fundamentalist government of Iran. The highlighted books include works by Vladimir Nabokov (Lolita), F. Scott Fitzgerald (The Great Gatsby), Jane Austen (Pride and Prejudice), and Henry James (Daisy Miller and Washington Square). Nafisi ties together interpretations of these novels with themes of oppression, totalitarianism, and blindness vs. empathy. Not surprisingly, her memoir has not been well received within Iran or by some Iranian ex-pats. Nafisi told the New York Times: “People from my country have said the book was successful because of a Zionist conspiracy and U.S. imperialism, and others have criticized me for washing our dirty laundry in front of the enemy.”

II. banning science books that challenge biblical narratives

There is no more telling indicator of the desperation of book bans than censorship of scientific breakthroughs. The examples we deal with in this section are worthy of particular consideration because the scientific method provides a framework in which subsequent evidence can convincingly confirm or refute competing viewpoints.

Heliocentrism:

The Judeo-Christian bible, if taken literally, places the Earth at the center of a universe created some 6000 years ago. Some apparent scientific backing for that geocentric view had been provided some 150 years after the birth of Christ by the Egyptian astronomer Ptolemy, who viewed the moon and Sun revolving around, and the other planets in the solar system executing rather complicated epicycles around, a stationary Earth slightly displaced from the center of the system. The first major milestone in the overthrow of geocentric models was the publication by Polish scholar Nicolaus Copernicus, just before his death in 1543, of On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres. Copernicus proposed a heliocentric mathematical model of the solar system, in which Earth and the other planets orbit the Sun. Copernicus’ model reasonably accounted for the observed motions of the planets from a vantage point on Earth without invoking the complication of Ptolemy’s epicycles, although it still assumed perfectly circular orbits.

The threat posed to the accuracy of the Bible by Copernicus’ theory was not lost on Christian hierarchies. Reacting already to rumors about the heliocentric model before even the actual publication of On the Revolutions, Martin Luther is quoted as saying the following in 1539:

“People gave ear to an upstart astrologer who strove to show that the earth revolves, not the heavens or the firmament, the sun and the moon … This fool wishes to reverse the entire science of astronomy; but sacred Scripture tells us [Joshua 10:13] that Joshua commanded the sun to stand still, and not the earth.”

In 1549 Luther’s principal lieutenant Philip Melanchthon advocated that “severe measures” be taken “to restrain the impiety of Copernicans.” There were, in fact, only a handful of Copernicans during the 16th century. One of them was a Spanish theologian, Diego de Zúñiga, who published in 1584 a Commentary on Job, which attempted to reconcile heliocentrism with Scripture. By decree of the Roman Catholic Inquisition in 1616, the works of Copernicus and Zúñiga were placed on the Index of Forbidden Books (Index Librorum Prohibitorum, see Fig. II.1), along with thousands of books and publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality.

The Index had been started in 1559, a century after Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press had made it possible to mass produce books and distribute them widely. In its original version, it banned Catholics from reading the entire works of 550 authors and hundreds more individual titles deemed at odds with official Church doctrine. The Index was not formally abolished until 1966 by Pope Paul VI. In addition to the scientific works discussed here, over the years it banned: the works of Protestant theologians such as Martin Luther and John Calvin; philosophical treatises by Thomas Hobbes, Rene Descartes, John Locke, George Berkeley, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Simone de Beauvoir; and the writings of John Milton, Daniel Defoe, Samuel Richardson, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Edward Gibbon, Stendhal, Balzac, Flaubert, Emile Zola and Andre Gide, among many others.

In fact, the Catholic Church’s determination that heliocentrism was heretical was a response to further explorations by Galileo. In 1610 Galileo published Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger) based on his astronomical observations with the telescope he had invented. Galileo’s data supported Copernicus’ model, which the Church had previously tolerated as a hypothetical, mathematical curiosity. It also provided descriptions of the Moon and planets at odds with earlier centuries of their treatment as perfect heavenly bodies composed of “quintessence.” The Church told Galileo to abstain from teaching or further discussing his support for heliocentrism.

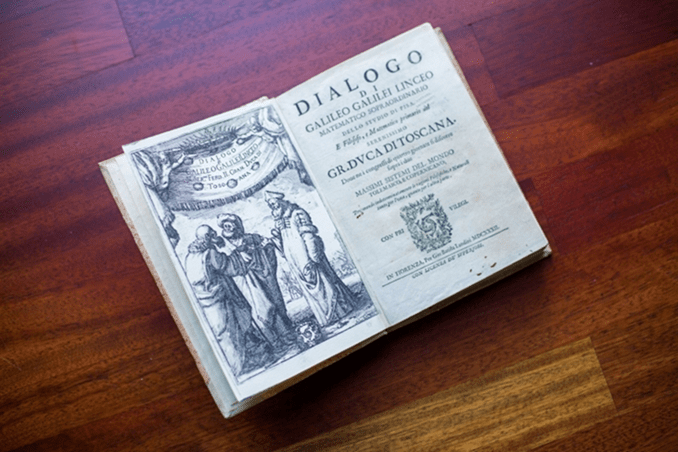

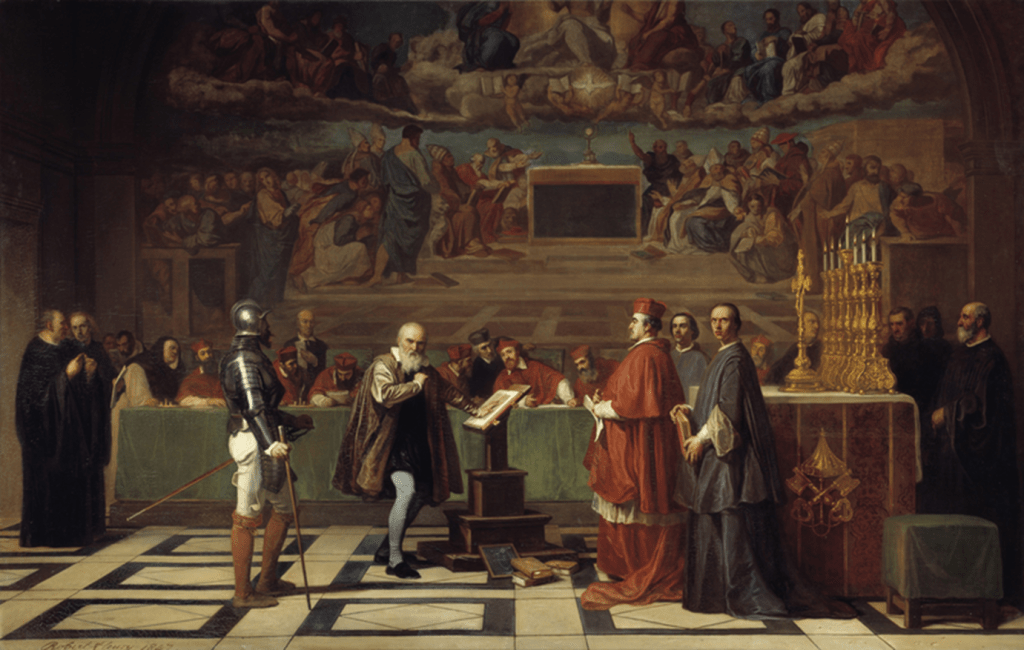

Galileo attempted to get around this ban in his 1632 Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (see Fig. II.2) by presenting an imagined conversation among three men, one pro-Copernicus, one pro-Ptolemy, and one neutral. But his strong arguments for a heliocentric model shone through and the Catholic Church, despite early patronage for Galileo from Pope Urban VIII, ordered Galileo to stand trial before the Inquisition for heresy in 1633. During the trial, under the threat of torture, Galileo was forced to recant his heliocentric views (see Fig. II.3), although legend has it that he muttered under his breath “And yet it moves.” After his conviction Galileo was sentenced to house arrest for the rest of his life and his books were banned until 1822.

But banning important books does not prevent their ideas from spreading and advancing. By the beginning of the 19th century, boosted by Isaac Newton’s theory of gravity and detailed accounting for planetary motions, it was widely accepted that the Sun is the center of the solar system. But the debate over Galileo’s treatment raged on within the Catholic Church hierarchy until almost the present day. In 1990 Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) quoted the philosopher Paul Feyerabend in a speech at La Sapienza University in Rome:

“The Church at the time of Galileo kept much more closely to reason than did Galileo himself, and she took into consideration the ethical and social consequences of Galileo’s teaching too. Her verdict against Galileo was rational and just, and the revision of this verdict can be justified only on the grounds of what is politically opportune.”

But only two years later Pope John Paul II wrote:

“Thanks to his intuition as a brilliant physicist and by relying on different arguments, Galileo, who practically invented the experimental method, understood why only the sun could function as the centre of the world, as it was then known, that is to say, as a planetary system. The error of the theologians of the time, when they maintained the centrality of the Earth, was to think that our understanding of the physical world’s structure was, in some way, imposed by the literal sense of Sacred Scripture…”

Evolution:

A similar scientific revolution against the “literal sense of Sacred Scripture” was launched with the 1859 publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. Darwin (see Fig. II.4) deduced the importance of natural selection for “survival of the fittest” from his observations of animal species, especially on the isolated Galapagos Islands. Darwin did not discuss the origins and evolution of mankind in this book, because he considered the subject too surrounded by prejudice and too devoid of fossil evidence. He waited until 1871, when he published The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. In the latter book he argued that the available evidence was consistent with humans also having evolved from a common ancestor shared with apes and originating in Africa. He suggested that differences among human races result in part from females exerting mating preferences for different traits among males of the species.

Darwin’s books, along with contemporaneous works by Alfred Russel Wallace, were in striking contrast to the biblical account of intelligent design of each species by a Creator and of humans, in particular, in God’s image, during a single creation week. That conflict of ideas led to multiple bannings of On the Origin of Species: from the library of Trinity College, Cambridge, where Darwin himself had been a student; from use in schools in Tennessee from 1925 to 1967; in Yugoslavia in 1935 and in Greece in 1937.

But perhaps having learned of the long-term ineffectiveness of book bans from the Galileo affair, the Catholic papacy refrained for nearly a century from making any official pronouncement about Darwin’s theories. Just as Galileo’s heliocentrism was dramatically advanced by the later development of Newton’s foundational theory of gravity, Darwin’s natural selection was put on much more solid grounds by the later development of genetics, which helped to explain the mechanism for natural selection. This led Pope Pius XII in the 1950 encyclical Humani generis to confirm “that there is no intrinsic conflict between Christianity and the theory of evolution, provided that Christians believe that God created all things and that the individual soul is a direct creation by God and not the product of purely material forces.”

Many Christians have, of course, been less generous to Darwin and evolution than Pope Pius XII. In our posts on evolution we have described numerous attempts by fundamentalist Christians, especially in southern U.S. states, to outlaw the teaching of natural selection or, at the very least, to present a balanced classroom treatment between evolutionary science and creation science (or its more modern form of Intelligent Design, ID) as two alternative explanations for the diversity of life on Earth. In the 1980s supporters of creation science wrote their own textbook intended to replace more standard school biology texts, with the title morphing from Creation Biology in 1983to Of Pandas and People in 1989, in the light of a 1987 Supreme Court case that found that “balanced treatment” laws represented unconstitutional infringements on the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Establishment Clause prohibits government laws respecting the establishment of a preferred religion.

The Foundation for Thought and Ethics (FTE), a fundamentalist Christian non-profit institution that first published Creation Biology, undertook an intensive and lengthy public campaign, with aid from the Institute for Creation Research, to get Of Pandas and People adopted for use in schools around the country. Their efforts have met mostly with failure. A few scattered school districts considered adoption of the book as a textbook, but it was rejected by local school boards or state textbook committees. In a few cases, it was allowed as an “extra resource,” but not as the official textbook, for school biology classes. The closest brush FTE had with success was the temporary 2004 decision by the Dover Area School District School Board in York County, Pennsylvania, to amend the district’s science curriculum to include Intelligent Design (ID) with Of Pandas and People used as a reference book. However, that decision was barred from taking effect by Judge John E. Jones in the resulting 2005 lawsuit Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District. The judge permanently barred the Dover School Board from “maintaining the ID policy in any school within the Dover Area School District, from requiring teachers to denigrate or disparage the scientific theory of evolution, and from requiring teachers to refer to a religious, alternative theory known as ID.”

Because evolutionary theory and the extensive evidence favoring evolution have been discussed in many books – and the same is true of Big Bang theory and the origins of the universe — it has become impractical for fundamentalist Christians to ban them all. The battlefield has thus turned, in the wake of failures to get Of Pandas and People adopted, to censoring school textbooks that make any mention of evolution. This effort goes well beyond biology textbooks and is centered in the state of Texas. For example, in 1982 the Texas State Textbook Committee “refused to adopt the top-rated world geography textbook, Land and People (Scott, Foresman, and Co.), because it contained the following sentence: ‘Biologists believe that human beings, as members of the animal kingdom, have adjusted to their environment through biological adaptation.’ The book also contained many passages stating that the earth and its features were millions of years old and that the universe began as stated by the Big Bang theory. These items were heavily criticized by a religious fundamentalist and creationist husband-and-wife team, Mel and Norma Gabler of Longview, Texas, whose sole business is reviewing textbooks. The Gablers are known in education circles throughout the nation as the most effective textbook censors in the country.”

At the time of that event, the Texas Textbook Proclamation contained a clause that required textbooks to describe evolution as a theory and “only one of several explanations of the origins of humankind” and in a manner “not detrimental to other theories of origin.” That clause, which had been adopted in 1973 largely at the urging of the Gablers, was subsequently repealed in 1984 under the threat of lawsuits. The repeal was a big deal nationally because Texas’ centralized textbook buying made it the largest purchaser of textbooks in the U.S. and, hence, made it difficult for publishers to offer different textbook versions for other states. This example highlights how a very small group of people can exert wildly disproportionate influence over the teaching of science in American public schools. Textbook censorship by states and local school boards has remained a prominent front in the fight to keep students from learning inconvenient truths when book bans fail.

III. prior waves of american book bans

The U.S., despite paying lip service to freedom of speech, has hardly been immune to book banning throughout its history. The first known banning in America, long before the establishment of the U.S., concerned a disagreement over Christian doctrine. A pamphlet written in 1650 by William Pynchon, a colonist in Massachusetts, asserted that “anyone who was obedient to God and followed Christian teachings on Earth could get into heaven.” His fellow colonists burned and banned his pamphlet because it contradicted Puritan Calvinist beliefs that only a select few were destined for heaven.

…the vast majority of historical and present American book bans manifest attempts to maintain and promulgate the myth that the U.S. was established to be a prim, white Christian society.

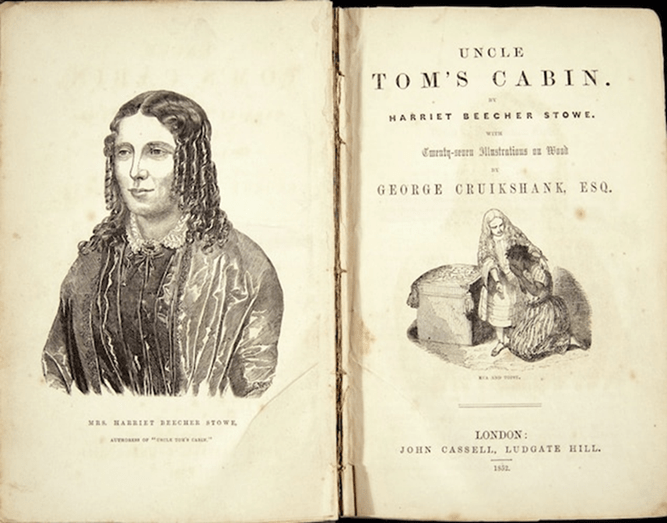

However, the vast majority of historical and present American book bans manifest attempts to maintain and promulgate the myth that the U.S. was established to be a prim, white Christian society. In fact, there is no mention whatsoever of God, Jesus Christ, or Christianity in the text of the U.S. Constitution or any of its 27 amendments. A late 19th-century push to add an amendment acknowledging “the rulership of Jesus Christ and the supremacy of the divine law” failed and the movement behind it faded. Most American book bans address the conflict of ideas about what America, or at least parts of America, stands for. In the southern states before and after the U.S. Civil War, this led to efforts to suppress texts that described slavery as evil. The most prominent ban was of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1851 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Fig. III.1), which was barred from stores throughout the Confederacy for its pro-abolitionist agenda. “In Maryland, free Black minister Sam Green was sentenced to 10 years in the state penitentiary for owning a copy of the book.”

PHOTOGRAPH BY FINE ART IMAGES, HERITAGE IMAGES/GETTY

After the war, Southern sensitivities continued to be offended by unsympathetic portrayals of the Confederacy’s loss as less than a noble “Lost Cause.” Well into the 20th century, the United Daughters of the Confederacy successfully banned school textbooks that argued that the war was fought and lost over the issue of slavery, rather than over the issue of states’ rights and the preservation of Southern culture and economy. As late as 1958 there were attempts to ban Garth Williams’ children’s book The Rabbits’ Wedding, because opponents maintained that its depiction of a marriage between a white rabbit and a black rabbit encouraged interracial relationships.

By a decade after the Civil War, the primary focus of U.S. book bans turned to issues of morality. A moralist government official named Anthony Comstock convinced the U.S. Congress to pass a law (known as the Comstock Act) in 1873 prohibiting the use of the U.S. Postal Service to mail any materials deemed “obscene” or “immoral.” Court cases stemming from applications of the Comstock Act and its subsequent clarifications led to a century of attempts by U.S. courts to define “pornography.” But in its initial applications the Act led to bans of “anatomy textbooks, doctors’ pamphlets about reproduction, anything by Oscar Wilde, and even The Canterbury Tales.” The law further “criminalized the activities of birth control advocates and forced popular pamphlets like Margaret Sanger’s Family Limitation underground, restricting the dissemination of knowledge about contraception at a time when open discussion about sexuality was taboo and infant and maternal mortality were rampant.” The ban on birth control remained in effect until 1936.

The Comstock Act was hardly the first historical attempt to use book and art bans to impose one view of morality on the masses. At the end of the 15th century, the local government in Florence, Italy came under the dominating influence of the friar Girolamo Savonarola (Fig. III.2). In addition to his prophecies and his charismatic personality, Savonarola was also contemptuous of articles that would tempt people toward sinful acts. He included a large class of books, paintings, sculptures, cosmetics and musical instruments in this class. Under Savonarola’s leadership, Florentines collected large quantities of these objects and burned them in what were called “bonfires of the vanities” in the Piazza della Signoria, a central square in Florence. Many priceless works of art were destroyed in these bonfires. In an ironic twist, in May 1498, after his politically motivated excommunication by Pope Alexander VI, Savonarola and two of his supporting friars were hanged on crosses and their bodies were burned in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria, the same location where the “bonfires of the vanities” had been carried out.

In the U.S. the city of Boston became the hotbed of Comstock Act bans. Works judged “indecent” in Boston included Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms. “The New England Watch and Ward Society, a private organization that included many of Boston’s most elite residents,… spurred the Boston Public Library to lock copies of the most controversial books, including books by Balzac and Zola, in a restricted room known as the Inferno… By the 1920s, Boston was so notorious for banning books that authors intentionally printed their books there in hopes that the inevitable ban would give them a publicity boost elsewhere in the country.”

By the 1920s booksellers, school and public librarians began to organize in order to advocate for people’s rights to read whatever they chose. Legal interpretations of obscenity and First Amendment protections began to shift in the 1933 court case The United States v. One Book Called Ulysses. In that case, Judge John M. Woolsey overturned a federal ban of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses that had been in effect since 1922. Despite his admitted distaste for Joyce’s novel, Woolsey ruled “that the depiction of sex, even if unpleasant, should be allowed in serious literature.”

Further clarification came in the 1957 Supreme Court case Roth v. United States. The Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s conviction of Samuel Roth, a writer and bookseller convicted of mailing pornographic magazines to subscribers. But the Court narrowed the definition of obscenity to include only works which are “utterly without redeeming social importance.” While a few legal challenges to this definition continued into the 1960s and 1970s, book bans for obscenity began to drop and more explicit art works began to flourish. Popular novels of the late 20th and early 21st centuries often included more or less graphic depictions of sex and occasionally descriptions of sexual obsessions. And on today’s internet it is often difficult to identify any “redeeming social importance” in much of the sexual material posted online.

Attention began to turn during the presidency of Ronald Reagan toward attempts to ban books that promoted narratives deemed unfit for a prim, white Christian nation from individual school and public libraries. Challenges to school boards and libraries rose dramatically to 700-800 per year, and often included requests to remove classics of American or world literature from the shelves.

Two relevant Supreme Court cases aimed to clarify the rights of school students. In the 1969 case Tinker v. Des Moines, brought by students who protested against the Vietnam War with black armbands during school hours, the Court ruled that “neither teachers nor students shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” The specific issue of school library book bans was addressed in a 1982 case brought by a group of students who sued a New York school board for removing books by authors like Kurt Vonnegut and Langston Hughes that the board deemed “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic, and just plain filthy.” In their ruling in Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico, the Supreme Court cited students’ First Amendment rights to conclude: “Local school boards may not remove books from school libraries simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books.”

Book bans just before the recent surge:

Despite those rulings, book challenges to school and public libraries continued at a fairly steady pace, before the current surge. To give some flavor of the types of books challenged, we consider the leading challenges during the three decades directly preceding the current surge. The American Library Association (ALA) maintains lists of banned and challenged books. Every decade they compile a list of the 100 most frequently banned and challenged books across the United States. By tracking the books most frequently banned and noting their subjects, we can recognize trends in the subjects that are the major targets of those who wish to censor certain topics. These are issues that particularly affect public libraries and schools in the U.S. We should mention that despite their efforts to compile a comprehensive list of book bans and restrictions, the American Library Association emphasizes that their list is at best a partial summary of all book bans. They estimate that their list comprises roughly 70% of the actual number of book bans across the U.S.

From the decade 1990 – 1999, here are the top ten banned and challenged books in the U.S.

- Scary Stories (series), by Alvin Schwartz

- Daddy’s Roommate, by Michael Willhoite

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, by Maya Angelou

- The Chocolate War, by Robert Cormier

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain

- Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck

- Forever, by Judy Blume

- Bridge to Terabithia, by Katherine Paterson

- Heather Has Two Mommies, by Leslea Newman

- The Catcher in the Rye, by J.D. Salinger

Of the top ten banned books, four are literary classics. Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a perennial addition to banned book lists. After it was first published, the book was attacked because it featured protagonists who were lower-class Americans. Thus, Huckleberry Finn was criticized as glorifying under-achievers; critics complained that literature should focus more on the accomplishments of distinguished citizens. More recently, Huckleberry Finn has come under attack for its frequent use of the “N-word.” Despite the fact that Twain’s book is actually anti-racist, it is now attacked on the grounds that it might be offensive to racial minorities.

Several of John Steinbeck’s novels find themselves under attack for their portrayal of the struggles of America’s poor. For example, Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men frequently appears on banned-book lists. A major reason is because of the profanity in the book; censors complain that it “takes the Lord’s name in vain.” Other criticisms cite the presence of racial epithets and violence in the book. J.D. Salinger’s novel The Catcher in the Rye has been criticized for its portrayal of a youth with serious mental health issues. According to the ALA, Salinger’s novel has been banned for having “excessive vulgar language, sexual scenes, things concerning moral issues, excessive violence, anything dealing with the occult and communism.”

A number of banned and challenged books were written by distinguished black authors. Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings made the top ten in this decade, but Alice Walker’s The Color Purple and three of Toni Morrison’s novels were listed in the top 100. These books depict the harsh realities of issues faced by American minorities. Attempts to ban or restrict these books often cite their negative portrayal of racial issues in America, or they attack the books as being inappropriate for reading by youth of a certain age. Efforts to ban books by minority authors show that America’s history of slavery and discrimination against minorities still evokes strong emotions. And it raises the suspicion that those seeking to censor these books may be influenced by racist motivations.

Judy Blume’s Young Adult novels about young women have been singled out for her frank treatment of issues of sexuality in the lives of young teens. There are five Judy Blume books in the top 100 banned books from this decade. During the decade 1990 – 1999, there are also banned books that deal with LGBTQ issues. In Michael Willhoite’s children’s book Daddy’s Roommate, a child learns that his divorced father is now living with a male partner. And Leslea Newman’s book Heather Has Two Mommies features a girl being raised by a lesbian couple. In addition to efforts to ban the books from libraries and public schools, these books are also subject to being stolen, burned or defaced by angry citizens. Books that describe sexual mores are also frequent targets of book banning campaigns. The Kinsey Reports or books by authors from the Kinsey Institute are perennial titles that appear on banned-book lists. The illustrated book Joy of Gay Sex by Charles Silverstein is another book that is a regular target of book-banning efforts.

The number one book on the 1990 – 1999 banned book list was the Scary Stories series written by Alvin Schwartz and illustrated by Stephen Gammell (see Fig. III.3). These books comprised an introduction to horror stories, and many people found Stephen Gammell’s black and white illustrations unsettling. While youngsters tended to read the book avidly and pass it around to their friends, many adults complained that the stories were too negative and that the illustrations were unsuitable for young adults. A schoolteacher complained about the stories to a Chicago Tribune writer “There’s no moral to them. The bad guys always win.” When a 30th anniversary edition of Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark was issued in 2011, the publishers used a new illustrator who produced much tamer pictures. However, they were criticized by readers who vividly remembered the original Gammell drawings from their childhood. Stephen King, who writes horror novels for more adult readers, had four of his novels appear on the ALA list for 1990 – 1999.

Here are the ALA top 10 banned and challenged books from the decade 2000 – 2009.

- Harry Potter (series) by J.K. Rowling

- Alice series by Phyllis Reynolds Naylor

- The Chocolate War by Robert Cormier

- And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell

- Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

- Scary Stories (series) by Alvin Schwartz

- His Dark Materials (series) by Philip Pullman

- ttyl; ttfn; l8r g8r (series) by Lauren Myracle

- The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky

A number of the works that appeared in the top ten list from 1990 – 1999 also appear in this decade. However, the number-one most banned or challenged book was, somewhat surprisingly, the Harry Potter series of novels by J.K. Rowling. The first Harry Potter book, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, was released in 1997, and the seventh and final book in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, was released in 2007. Harry Potter became a blockbuster book series. As of February 2023, the Harry Potter books have sold over 600 million copies worldwide, making it the best-selling series in history. In the U.S., the final installment of the Harry Potter series sold 8.3 million copies in the first 24 hours of its release. A series of eight Harry Potter films were released. In 2016, the total value of the Harry Potter franchise was estimated at $25 billion dollars.

Because of the amazing success of the Harry Potter series, the books came under fire from Christian fundamentalists. Those seeking to ban or restrict the access of Harry Potter books in libraries and schools claimed “it was anti-family, discussed magic and witchcraft, contained actual spells and curses, referenced the occult/Satanism, violence, and had characters who used ‘nefarious means’ to attain goals.” It seems unlikely that young readers of the Harry Potter series believe the wizardry described in these novels to be real; however, around the U.S. there were thousands of attempts to remove Harry Potter books from library shelves and school libraries. Many parents seem to underestimate their children’s ability to distinguish fact from fiction.

Another author whose works appear in the top ten banned book list for this decade is Lauren Myracle. She wrote a series titled Internet Girls. The books simply consist of a series of text messages that are purported to be sent between girls of high school age. They describe what the girls are thinking and experiencing during their teenage years. But the books have been the focus of widespread efforts to ban them from libraries and schools. The first point of contention focuses on the language that appears in the novels. The use of words such as “fuck,” “penis” and “condom” are often cited as reasons to ban the book; although according to Myracle herself, the words most frequently mentioned in book-banning attempts are “thongs, tampons, and erections.” In addition, some of the experiences described in the books have led to demands that they be forbidden to young readers. For example, in one novel a high-school girl attends a party thrown by college students. The girl is persuaded to remove her shirt and be photographed by the college students. Although the author claims that the scene should convince young readers not to engage in such activities, critics claim that the author is encouraging such behavior.

Here are the ALA top ten banned and challenged books from the decade 2010 – 2019.

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- Captain Underpants (series) by Dav Pilkey

- Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher

- Looking for Alaska by John Green

- George by Alex Gino

- And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell

- Drama by Raina Telgemeier

- Fifty Shades of Grey by E. L. James

- Internet Girls (series) by Lauren Myracle

- The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

The Harry Potter series, which topped the “most banned and challenged” list from the decade 2000 – 2009 has disappeared altogether from the top 100 list for 2010 – 2019. It is likely that the tremendous success of the Harry Potter movie series muted the criticism from book censorship advocates.

A curious entry in this decade’s top 10 is Captain Underpants, a series of graphic novels by Dav Pilkey (see Fig. III.5). The books describe the exploits of two school children, George Beard and Harold Hutchins. The boys pull a number of pranks at their school, and they invent a superhero called Captain Underpants who wears only a cape and a pair of underpants. The books have been criticized for “offensive language,” although the language is actually rather mild. Most of the complaints claim that the material in the book is unsuitable for elementary school children. The Captain Underpants books are written in a childlike fashion that appeals to young readers. Furthermore, Pilkey’s frequent reference to underwear in the graphic novels is bound to interest and amuse his readers.

In his novels, Dav Pilkey is clearly kidding uptight parents when his first book contains a “Sturgeon General’s Warning” – “Some material in this book may be considered offensive by people who don’t wear underwear.” The novels are also criticized for their depiction of violence. In a chapter titled The Extremely Graphic Violence Chapter (presumably designed to provoke criticism from adults), the boys beat up a pair of robots that are attacking them. This scene begins with a disclaimer “WARNING: The following chapter contains graphic scenes showing two boys beating the tar out of a couple of robots. If you have high blood pressure, or if you faint at the sight of motor oil, we strong urge you to take better care of yourself and stop being such a baby.”

As Dav Pilkey possibly intended, his novels were widely criticized by people advocating censorship of books. And as might be expected, the controversy over book banning greatly increased the sale of the Captain Underpants series. It is difficult to understand the motivations for banning these novels. It seems that the ‘offensive’ behavior is mild and is presented ironically. The novels simply portray a couple of young boys who like to pull pranks, and who invent a ‘superhero’ who flies around in his underpants.

The number one most banned/challenged book from 2010 – 2019 was The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie. The ALA states that this was one of the most frequently banned books in their history of tabulating these numbers. Alexie’s novel (Fig. III.6) featured a Native American teenager who had grown up on a reservation in Washington state and who was trying to overcome several disabilities. The 14-year-old protagonist Arnold transferred from a school on ‘the rez’ to a predominantly white school. Unfortunately, most of his friends on the rez see Arnold as a traitor for transferring his school. And Arnold is forced to confront a number of obstacles in his effort to improve his lot in life, and to deal with the handicaps of race, poverty and disability. Apparently, the reasons most frequently cited in attempts to restrict this book included the use of profanity, sexual references (including a description of masturbation by a youth), and allegations of sexual misconduct by author Sherman Alexie.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian was hailed by literary critics. For example, a review in Publisher’s Weekly called this book “the Native American equivalent of Angela’s Ashes, a coming-of-age story so well observed that its very rootedness in one specific culture is also what lends it universality, and so emotionally honest that the humor almost always proves painful.” The novel also garnered a number of awards, including a National Book Award for Young People’s Literature in 2007 and a Young Adult Library Services Association “Top Ten Best Books for Young Adults” award in 2008. Regardless of those awards (or perhaps because of them?), for several years running the book was singled out for book-banning efforts across the U.S.

The list of the top 100 banned/challenged books during the decade 2010 – 2019 includes a number of classic books by acclaimed authors, that seem to appear on lists in every decade. So, authors such as Mark Twain, Harper Lee, Toni Morrison, Aldous Huxley, John Steinbeck, Anne Frank and George Orwell make an appearance in this list. A more recent entry to the top 10 list is 50 Shades of Grey by E.L. James. That novel is told from the point of view of a woman who comes under the control of a man who coaches her in sexual practices such as bondage, dominance and sado-masochism. The topic seems a natural for people who wish to censor the book, or otherwise prevent American youth from encountering it. The 50 Shades of Grey trilogy sold an astonishing number of copies – the collected works of E.L. James have sold more than 165 million copies. And three movies based on the trilogy apparently grossed more than a billion dollars worldwide. The books won a number of awards from readers, despite the fact that literary critics tended to pan the writing. A review by Bryony Gordon in The Daily Telegraph described the male lead billionaire Christian Grey as “A cut-price Mr. Darcy [of Pride and Prejudice] with nipple clamps … the joke is taken too far … creepy doesn’t even begin to cover it.”

Over the past 30 years, the number and type of books that have been banned, restricted or otherwise challenged in schools and public libraries have remained relatively constant. The types of novels on book-banning lists feature descriptions of sexual practices, or they include accurate but disturbing descriptions of the racial history of our country. In other cases, books are attacked because of crude language in the text. Many classic novels have been banned because of their grim portrayals of warfare, or because of leftist views of their authors. The books that appear on American Library Association top-100 lists have generally been the focus of organized efforts across the country; in many cases they result from organized campaigns by fundamentalist Christian groups.

However, as we will see in Part II of this post, in the past few years the book banning movement has become supercharged. Populist groups associated with Donald Trump supporters have joined with white Christian nationalist organizations, and have made book banning a major issue supported by the Republican party across the U.S. This has meant that book-banning efforts are much more widespread and coordinated than has been the case in prior years. We will examine these new movements in detail.

— Continued in Part II —