Update 04/12/2025: As you may have already seen from the worldwide press coverage (for example, see Fig. 1), dire wolves are back. Temporarily and, as we’ll show below, with some very serious caveats. The original dire wolves were predators that roamed the Americas during the last Ice Age. Fossils indicate that they were comparable in size to the largest of modern Yukon and Northwestern wolves, with somewhat larger heads, stronger jaws, and sharper teeth. Their likely prey comprised large mammal herbivores of the period: extinct camels, horses, and bisons, ground sloths, “dwarf” pronghorns, and even mastodons. The dire wolves became extinct some 9,000-10,000 years ago, probably because most of their prey had disappeared.

In part II of this post below we described ongoing efforts to revive a number of extinct species, yet we never mentioned the dire wolf. In fact, the Dallas-based biotech company Colossal Biosciences that has now succeeded in producing dire-wolf “look-alikes” (to be explained below), did not even advertise this project publicly as one of its major de-extinction aims. Colossal was founded by geneticist and de-extinction enthusiast George Church of Harvard and technology entrepreneur Ben Lamm, who has to date attracted private funding of nearly half a billion dollars to establish scientific research and bioengineering aiming to revive woolly mammoths, dodos, and Tasmanian tigers (thylacines), all of which we discussed in this post. Dire wolves appear to have entered the picture surreptitiously for two reasons: first, their de-extinction was viewed as technically somewhat less challenging than the other projects, with hounds available to serve as surrogate mothers; second, dire wolves have been popularized in modern culture, most significantly in the HBO series Game of Thrones, based on the novels by George R.R. Martin. Hence, his appearance in Fig. 1 as one of the first “outsiders” to Colossal to have viewed and handled the new pups. The de-extinction of dire wolves has basically served as a prototype project for Colossal, a proof of principle that its techniques will work. The project’s success will undoubtedly help to secure even more funding.

Today, George Church serves as a scientific advisor to Colossal and Ben Lamm is the CEO. Beth Shapiro, the ancient DNA expert who features prominently in our post below, came on board in 2024 to serve as Chief Science Officer. Shapiro has described the processes and limitations of de-extinction very well in her book How to Clone a Mammoth. The first step in the process used by Colossal involves the extraction of DNA from fossils of the extinct species. In the case of the dire wolf, this was accomplished by extracting DNA from a thirteen thousand-year old dire wolf tooth found in an Ohio cave. Colossal scientists were able to reconstruct about 91% of the dire wolf’s entire genome, an unusually good result for ancient DNA.

Once you have reconstructed ancient DNA, there are three basic next steps in the de-extinction process:

- Extract a mature tissue cell from a genomically close living relative of the extinct species – in this case, from a grey wolf – and convert it by a well-established technique to an induced pluripotent stem cell, iPSC. iPSCs are analogous to embryonic stem cells, and once in place in a growing embryo they can re-differentiate into multiple distinct defined-function cell types.

- Use CRISPR technology to edit the genes in the iPSC to substitute in genetic features deduced from the extracted ancient DNA.

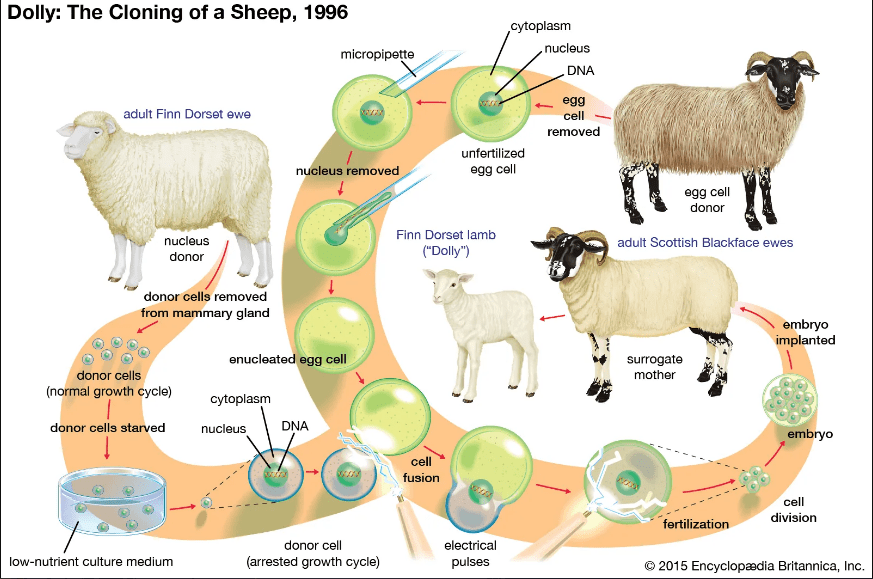

- Inject the edited iPSC to replace the nucleus of an unfertilized egg cell taken from a living female of a relative species and allow that modified egg to gestate within the relative female. Optimally one would want to use a grey wolf surrogate mother, but much more is known about the reproductive details and breeding of dogs and they are much easier to monitor during gestation. So for the dire wolves, hounds were used as the female hosts.

If you wanted to create an exact clone of the extinct species you would have to make as many simultaneous CRISPR edits as possible in the iPSC to reproduce the ancient genome. Even if the ancient dire wolf genome had been 100% reconstructed, the technology to do this does not yet exist. The Colossal scientists determined that the dire wolf DNA was a 99.5% match to the grey wolf DNA. But the grey wolf genome comprises over 2.4 billion base pairs. So a 0.5% mismatch implies about 12 million base-pair differences between grey and dire wolves, far too many edits to make with today’s CRISPR technology. In fact, the Colossal researchers set an animal gene-editing record by making a total of 20 edits to 14 distinct grey wolf genes. They chose edits designed to induce changes that would lead to a larger size, larger head with pronounced muzzle and ears, and fluffier, paler fur than are typical for grey wolves. They could tell from the ancient DNA that the dire wolf coloring was paler than that of a grey wolf, but there is no way of knowing if it was as snowy white as seen for the pups in Fig. 1. In this sense, what the Colossal team were hoping to create were dire-wolf-like grey wolves (birthed by a hound mother), just as George Church’s ultimate goal, described in the post below, is to create a woolly-mammoth-like Asian elephant. Indeed, it is probably incorrect to think of the new dire wolves as a distinct species; they have so much grey wolf DNA that they could in all likelihood mate with grey wolves if they were given the opportunity to do so when they reach adulthood.

The Colossal researchers were able finally to insert 45 genetically modified embryos into two surrogate mother dogs. One embryo in each mother – both drawn from the same edited iPSC – survived to term during the 60-day gestation period, during which the mothers were kept under close supervision at a secure animal center. The new pups were extracted by Caesarian section because they would probably have been too large to survive, along with the surrogate mothers, a normal vaginal birth. The two dire wolf “look-alikes” – named Romulus and Remus — are in fact identical twins; they share the same DNA despite coming from two different surrogate mothers. The surrogate mothers nursed them for the first few days, but the pups were then switched to bottles.

Romulus and Remus are by now about seven months old and reside on an undisclosed 2,000-acre property somewhere in the U.S. They have been observed to behave differently from dogs in several ways, but it is impossible to know if their behavior mirrors that of ancient dire wolves. A third, younger dire wolf “look-alike” pup – named Khaleesi – has also been produced. As D.T. Max, the author of a very recent New Yorker article on the dire wolves puts it, Romulus and Remus “are now at the age when their parents would teach them to hunt, but of course they have no parents; in fact, they have never seen other wolves.”

Colossal’s ultimate goal is to modify ecosystems by introducing multiple individuals of revived species, whose extinction removed critical pieces from the ecosystem, and then allowing those individuals to mate and breed normally. But that is not their goal for the dire wolves. Ben Lamm told D.T. Max “that Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi will not be allowed to breed; moreover, the company anticipates genetically engineering just three to five more of the animals. They will be kept on their preserve, protected by a ten-foot-high security fence and surveilled by drones—and visited, one suspects, only by the occasional billionaire.” The dire wolves are the first successes in creating animals that have substantial DNA resurrected from extinct species. That is a major breakthrough for science and for Colossal Biosciences. But it is a dead-end project for the dire wolves themselves, who will once again become extinct when these several individuals die. It is far from clear that they could survive in the wild without parents and other species members to learn from. That is a challenge that will also be faced by early successes in all future de-extinction efforts.

For a Colossal promotional video heralding the dire wolf success, Donald Trump’s Department of the Interior sent a draft statement indicating that the births were proof that “innovation – not regulation – had spawned American greatness.” We take away a very different message. Apart from the specific goals of de-extinction, Colossal has demonstrated fairly extensive CRISPR gene editing to make very significant changes to a species’ phenotype – its appearance and structure. An era of designer human babies and attempts to create a class of “super-soldiers” cannot be far behind. Regulation of such “innovation” is needed sooner rather than later!

An even more worrisome takeaway was enunciated by Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum when he claimed that “The revival of the Dire Wolf heralds the advent of a thrilling new era of scientific wonder, showcasing how the concept of ‘de-extinction’ can serve as a bedrock for modern species conservation.” His accompanying comments made clear that he saw this as a reason to ignore or repeal the Endangered Species Act. Why spend millions to save an entire species from extinction when there are private investors willing to devote billions to the risky project of bringing back “look-alikes” of extinct species one by one?

July 9, 2024

III. Biotechnologies, challenges, and major advocates for de-extinction

In this section we will review the biotechnology approaches that allow for consideration of de-extinction. We will pay some attention to the challenges facing each approach.

Cloning:

Cloning, in general, refers to any process to generate a genetically identical copy of a cell or an organism. For example, some organisms, such as bacteria, reproduce by cloning themselves rather than via sexual reproduction. Many human cells, such as those of the skin or the gastrointestinal tract lining, which regenerate themselves during life do so by cloning, i.e., by splitting into two cells with identical copies of its chromosomes. However, in the context of de-extinction, cloning refers to a specific technique known as somatic cell nuclear transfer. The process, as applied to the cloned sheep Dolly, is illustrated in Fig. III.1. A somatic cell is extracted from a living mammal to be cloned, and its nucleus, containing the paired chromosomes that were given to the mammal by its two parents, is injected into an unfertilized egg cell extracted from a different female mammal, which has had its own DNA-carrying nucleus removed. Once the somatic cell nucleus is inside the egg, a mild electrical current is used to stimulate cell division and embryo formation. The embryo must successfully reprogram the specialized somatic cell nucleus into an unspecialized embryonic stem cell, and this step is quite inefficient. The embryonic stem cells will subsequently begin to differentiate into the wide variety of specialized cells needed by the many bodily systems of the fetus. The embryo is then implanted within the womb of a surrogate mother, where it hopefully gestates until birth. In the case of Dolly, 277 distinct cloned embryos produced only one successful live birth.

Somatic cell nuclear transfer can only work if the somatic cell is extracted from a living animal, although the cell may then be frozen and preserved in a repository such as the Frozen Zoo at the San Diego Zoo. Thus, for cloning to work in the context of de-extinction, the species to be revived must have gone extinct in the very recent past and had cell samples extracted and preserved. Even then, a cloned embryo must undergo gestation in the womb of a different, though related, species. There is very limited experience with such cross-species cloning. In the attempt to clone the now extinct Pyrenean ibex, the surrogate mother was a hybrid of a domestic goat and a different species of ibex.

Beth Shapiro points out another limitation of cloning: it is not applicable to bird species. “In a mammal, the egg whose nucleus is removed and then replaced is collected from the female reproductive tract after it has matured but before it is fertilized. At precisely this stage, the egg is primed to reprogram the nucleus of the somatic cell. It turns out to be extremely challenging to collect bird eggs that are at this stage of development. The reproductive tract in birds is long and sinuous, and the yolk is tricky to recover prior to fertilization. If we wait until the egg has been laid, the [stem] cells in the embryo will have already started to differentiate, and the embryo—which is held in position within the egg by many layers of twisted fibers—will be too large to remove.”

The near impossibility of extracting living or preserved cells from long extinct animals has not completely quelled interest in literally cloning woolly mammoths. Akira Iritani of Japan’s Kinki University has been hoping for many years now to find a mammoth so well preserved in ice from the Ice Age that he can find frozen somatic cells for a cloning operation or even sperm cells his team could use to directly impregnate a female Asian elephant as the first step in a selective breeding process. Some remarkably well-preserved mammoth body parts and, in the case of Fig. III.2, even a whole mammoth have indeed been found trapped in mud and ice within the now thawing Siberian permafrost. But just as for insects trapped in amber, a well-preserved physical specimen is not at all immune from DNA degradation. As Beth Shapiro explains: “While the mummy was slowly freezing, microbes from the animal’s gut and the environment would colonize tissues throughout the body, decomposing the animal from the inside and simultaneously destroying the DNA…the DNA within even the best preserved mummies tends to be in bad shape compared with the DNA that is preserved in bones.” And, as we’ll see below, even that DNA from bones can be recovered only in relatively small fragments, nowhere near good enough to support somatic cell nuclear transfer.

Induced pluripotent stem cells:

It is no longer necessary to rely on an embryo itself to reprogram somatic cells injected from another animal into embryonic stem cells. Shinya Yamanaka and Kazutoshi Takahashi discovered in 2006 that it was possible to do such reprogramming more efficiently in a tissue culture in a laboratory than inside a donated egg cell. The reprogramming of a mature somatic (unipotent) cell into a so-called induced pluripotent stem cell, iPSC – similar in function though not identical to an embryonic stem cell – is effected by the introduction of four genes that encode the production of proteins which bind to specific DNA sequences and control which genes are turned on and when. The iPSCs can then re-differentiate into multiple types of cells. For this discovery with important implications for regenerative medicine, Yamanaka shared the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for the discovery that mature cells can be reprogrammed to become pluripotent.”

In de-extinction research, it is possible in principle to use such iPSCs generated from a living animal, to edit the genes of the iPSCs to substitute at least some of those sequenced from a long-extinct relative species, and then to inject those edited iPSCs into the nucleus of an unfertilized egg cell from a living relative female to start a modified cloning procedure. This is the basic scheme envisioned to generate a mammoth-like elephant – one with a genome adaptable to life in the frigid north — by George Church and his team at Colossal Biosciences. The team has just passed a milestone for their project by managing for the first time to create an iPSC from a somatic cell extracted from a mature Asian elephant, the mammoth’s closest living relative species.

Ancient DNA:

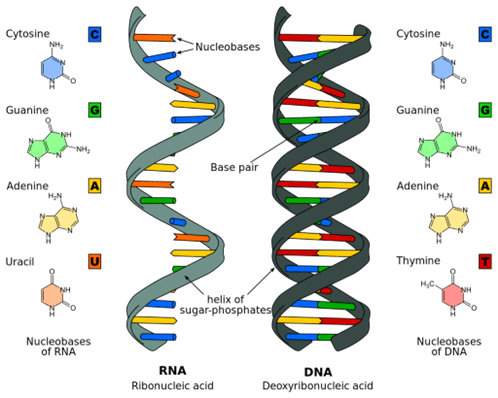

The genome of each species considered for de-extinction comprises pairs of chromosomes, with one of each pair contributed by an individual’s mother and the other by the father. Each chromosome consists of long DNA chains of paired nitrogenous nucleotide bases, with each pair bonded to one another and to a double helical backbone of sugar phosphates, as illustrated in Fig. III.3. The sequencing of the base pairs encodes the genetic information. A typical mammal’s chromosomes may each contain hundreds of millions of base pairs and the genome overall may comprise billions of base pairs. The human genome, now completely sequenced, contains a total of 3.2 billion base pairs distributed among 23 chromosomes, which are paired to make 46 total chromosomes in each individual. The genome of the Asian elephant, the nearest living relative species to woolly mammoths, contains about 3.4 billion base pairs. But over the 5 million years or so that woolly mammoths and Asian elephants genomically diverged (see Fig. I.1), it is estimated that “something like 1.5 million DNA changes have accumulated between the two species.”

DNA sequencing is the determination of the precise ordering of A, C, G, and T bases (see Fig. III.3) within each chromosome. When scientists sequence DNA they cannot typically analyze a fragment longer than several thousand base pairs at one time. Thus, they must first cut chromosomes into such fragments and sequence each fragment. To reconstruct the entire genome, it is necessary to figure out how a million or so of such fragments fit together. Reconstructing the genome of a long-extinct species is much more challenging still, because the recoverable fragments from dug up bones or body parts are usually much shorter than several thousand base pairs and most of the fragments are missing. Worse still, the recovered fragments may be contaminated by DNA from microorganisms that invaded the body part after the animal’s death or from plant roots that grew around the recovered body part when it was buried underground.

Why does DNA deteriorate so much in extinct species? In living cells, DNA has self-repair mechanisms to undo temporary damage from ultraviolet or other forms of radiation or from pathogens, for example, as well as from intentional damage inflicted by molecular scissors to be described below. Not only does this repair mechanism go away in dead organisms, but enzymes contained in each cell with the function of destroying invading pathogens and cutting out damaged DNA, live on for some time to break down dead DNA. Furthermore, bacteria, possibly even from the animal’s gut, and fungi invade the decaying cells and further fragment the DNA. The longer the animal has been dead, the more extensive the DNA degradation.

The most completely assembled ancient DNA at this point is that of Neanderthals, reconstructed by a team led by Swedish geneticist Svante Pääbo from DNA samples extracted from three different Neanderthal bones. In Beth Shapiro’s account, “Each bone contained less than 5 percent Neandertal DNA, with the remaining 95 percent or more comprising mostly environmental DNA – soil microbes and their pathogens, plants, and the like. Of the Neandertal DNA sequences that were recovered from these bones, the average fragment length was 47 base-pairs. The human genome contains 3.2 billion base-pairs, so this is a bit like having a puzzle that can only be solved by correctly assembling 68 million puzzle pieces. Of course, thanks to damage and contamination, what they actually had was far more pieces than they needed, some of which were from the same puzzle but cut in a different way and some of which actually belonged to a different puzzle.” Pääbo’s team managed the reconstruction by using the already mapped human genome as a template, from which only a few percent differences were expected. For this monumental reconstruction Pääbo was awarded the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for his discoveries concerning the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution.”

Reconstructing ancient DNA for species considered for de-extinction will follow the approach used by Pääbo. But homo sapiens and homo neanderthalensis are believed to have branched off from a common ancestor (homo Heidelbergensis) roughly a half million years ago. The corresponding branch point for woolly mammoths and Asian elephants, for example, is believed to have happened more like five million years ago. Thus, one expects considerably greater genomic differences to have arisen over time in their case than between humans and Neanderthals. The modern template for ancient genome reconstruction will not be as good as humans provide for Neanderthals; more guesswork will be involved in the reconstruction. For mammoths and their contemporary Pleistocene mammals, the best one can hope for today is to reconstruct pieces of the genomes. With luck, the reconstructed pieces will contain non-elephant genes that were responsible for mammoths’ ability to adapt to much colder climates. The woolly coats were part of that adaptation. But there must also have been changes in hemoglobin genes that allowed for the construction of red blood cells capable of transporting oxygen around the animal’s body more efficiently, as needed for survival in frigid climates. The hope is to identify several such specific gene alterations that could then be CRISPR-edited into Asian elephant iPSCs, to create mammoth-like elephant embryos.

CRISPR gene editing:

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing has been available for about a decade now. Its discovery was triggered by the mapping of bacterial genomes, which revealed repeated sequences that allowed the bacteria to identify the DNA or RNA of invading viruses and to disable those viruses. The functioning of the CRISPR-Cas9 molecular assembly was worked out by Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, leading to their 2020 Nobel Prize. Its application to gene editing is illustrated schematically in Fig. III.4. A single-stranded guide RNA molecule is engineered to match the nucleobase sequence in the segment of DNA to be edited. The guide RNA attaches itself to one strand of the targeted DNA section and shows the Cas9 “molecular scissors” enzyme precisely where to cleave both strands of the DNA. The cleavage creates a hole that can then be filled in by one of the cell’s natural repair mechanisms: either non-homology end-joining to sew the divided DNA ends back together or homology-directed repair, in which the hole is filled by copying in a nearby DNA template section. That template could come from the other chromosome in the pair or from a payload gene brought in with the CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Other gene editing techniques predated CRISPR, but the CRISPR method is easier, cheaper, and more efficient to use and it has revolutionized the field of genome editing.

In applying CRISPR to de-extinction one would like to edit as much of the recovered genome from an extinct species as possible in to replace corresponding, altered parts of the genome of the nearest living relative species. But there are limits to the application of CRISPR. One can only replace a few genes at a time in one CRISPR application. The current record for most edits in a single cell was obtained by George Church’s group at the Wyss Institute at Harvard. They made 13,000 distinct DNA changes within a human cell but all of them “targeted the same change in a gene that occurs in 3,000 duplicated copies across the genome.” Furthermore, CRISPR is not perfect. It occasionally makes DNA cuts and changes in non-targeted sections of DNA. Some of these off-target collateral damages might be toxic. While there is ongoing research aimed at reducing the occurrence of off-target effects, such collateral damages could undermine an otherwise successful de-extinction experiment.

George Church’s team at Colossal Biosciences aims to use CRISPR to edit in a few selected genes recovered from woolly mammoth DNA to an induced pluripotent stem cell generated from a somatic cell drawn from a living Asian elephant. When that edited iPSC is injected into an unfertilized Asian elephant egg cell in a process akin to normal cloning, it will hopefully generate a mammoth-like elephant embryo to develop during gestation within an Asian elephant womb.

But as noted earlier, scientists do not know how to extract suitable unfertilized egg cells from birds. There are ongoing projects to revive extinct bird species, particularly the passenger pigeon (see Section IV). These efforts must apply CRISPR editing not to iPSCs, but rather to primordial germ cells. These are tiny cells present in bird embryos just after an egg is laid that will develop into sperm or egg cells on their way to sex organs that begin to develop in the embryo about 24 hours later. Primordial germ cells can be grown in a laboratory dish, where their genome can be edited with genes from a related extinct bird species. The edited primordial germ cells can then be injected into the embryo during the second 24-hour development period, where they, too, will develop into (now edited) sperm or egg cells. Beth Shapiro: “When the chick hatches from the egg into which the genetically modified primordial germ cells were injected, that chick itself will not be genetically altered. Instead, the genetically altered cells will be hiding out in its sex organs. The first time the genetically altered genes will be expressed will be when that chick grows up and has its own baby chicks.”

Natural and artificial gestation:

Another significant challenge to de-extinction hopes is the requirement that a cloned or gene-edited embryo get successfully implanted in the uterine lining of a female from a related species and then receive during fetal development all the appropriate hormones and nutrients that would have been provided by a now extinct mother of the same species. Will the surrogate womb environment foster the expression of the edited genes copied from an extinct species? The revived fetus must not grow too large to threaten the surrogate mother during gestation or at birth. For example, there has been discussion of reviving Steller’s sea cows, a marine mammal that was often about nine meters in length and weighed up to ten tons. If the surrogate mother for a Steller’s sea cow de-extinction had to be its closest living relative, the significantly smaller dugong, the calf at birth would probably exceed the length of the mother. But it also must not end up too small, compared to its extinct cohort, to thrive in the habitat and ecosystem reserved for it. And if the gestation is long – Asian elephant gestations last 623-729 days – is it unfair to the surrogate mother to “waste” that time on a fetus unlikely to survive much past birth (as was the case for the cloned bucardo), when she could have been pregnant with a baby of her own species?

These potential issues with cross-species gestation for at least some de-extinction projects have led some researchers to contemplate following up a projection made in Aldous Huxley’s 1932 dystopian novel Brave New World for in vitro gestation. In Huxley’s novel human women no longer get pregnant, some of them just donate eggs for laboratory fertilization, duplication, and embryo/fetus development. To date, artificial wombs have been considered to aid the development of fetuses in danger of premature birth. A research team from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia has developed a “biobag” to provide hormone and nutrient support within an artificial amniotic fluid for extremely premature lambs. They have shown “that fetal lambs that are developmentally equivalent to the extreme premature human infant can be physiologically supported in this extra-uterine device for up to 4 weeks.” Colossal Biosciences is now working to develop an artificial womb for revived woolly mammoth gestation, because “an enormous amount of energy expenditure is required for gestation and is often unsuccessful due to fractured populations, late sexual maturity and extremely long gestation times.”

Backward breeding:

While the opportunity to find novel applications for some of the biotech wizardry outlined above is undoubtedly part of the attraction for some scientists working on de-extinction, there is a lower-tech option that might work for some extinct species. It’s called back-breeding and it represents a selective breeding approach to unwind some aspects of evolution. When an evolutionary ancestor is superseded by animals better adapted to survive current environments, the ancestral genes are not uniformly replaced. Some of the genes that contributed to unique physical and behavioral characteristics of the now extinct species probably persist, along with many evolved genes, in some fraction of its descendants. If one gathers good DNA sequencing for the extinct species of interest, it is then possible to identify members of the descendant species which share more of the now outdated genes and breed them together. Even without the extinct DNA one can identify current animals which come closer to the appearance of the extinct species and use them for selective breeding. After a number of generations in the lineage of such selective breeding a subset of the current species will look and act similarly to the extinct species of interest, although they are unlikely to fit genomically within the extinct species.

Back-breeding is most likely to succeed for species that became extinct in the not-too-distant past and whose descendant species are common in today’s world. This approach is being tried today to reconstruct features of aurochs, a type of large, powerful, wild cow that is an ancestor of today’s domesticated cattle. Aurochs went extinct during the 17th century. We will describe attempts to revive them in the next section. Another target is the quagga, a subspecies of plains zebra that died out in 1883.

IV. some specific de-extinction projects

De-extinction is highly challenging and will be quite expensive to carry out. Clearly, it would make no sense to try to revive an extinct species that is highly likely to go extinct again, or one for which the technical procedures are unlikely to work well. There are, in our judgment, a number of criteria that should be satisfied in choosing target species:

- There should be significant demand to see the species revived and living beyond captivity.

- There should be positive benefits beyond satisfying the curiosity or guilty consciences of humans to restoring the species.

- There should be living species with sufficiently similar genomes to serve as tissue donors and surrogate mothers.

- There must be sufficient access to ancient DNA from the target species, or to frozen living cells, to facilitate gene editing or cloning.

- There must be suitable wild habitat either existing on Earth or prepared by humans for a resurrected species to thrive, if the de-extinction were to succeed.

- There should be sufficient understanding of the conditions that caused the species’ extinction in the first place to remove those causes, to the extent possible, in the habitats and ecosystems into which the revived species are to be released.

- Significant study should be addressed to the possible impacts introduction of a revived species would have on the ecosystems into which they would be released.

- Care should be taken that gene editing of ancient DNA does not inadvertently include ancient pathogens that might prove deadly to either the revived species or ones that share its ecosystem. One must also worry that revived species may be exposed to new pathogens to which they never developed immunity in their previous existence.

- Humans must find ways to train the first young successful products of de-extinction in ways to survive in their intended wild habitat, without getting them so adapted to human captivity that they will die out in the wild.

We outline below some of the ongoing de-extinction projects around the world. Readers can decide whether any of them satisfy all the above criteria.

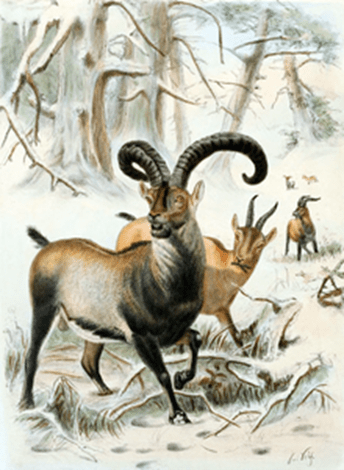

Pyrenean ibex:

The Pyrenean ibex (see Fig. IV.1), also known as the bucardo, went extinct quite recently, a victim of overhunting by humans during the 19th and 20th centuries. A tissue sample was taken from the last surviving bucardo, a female living in a national park in the Pyrenees, before she died in the year 2000. Cells from that frozen tissue sample were used in attempts to clone the last bucardo using egg cells taken from domestic goats. 208 different goats served as surrogate mothers for the cloned embryos that survived out of 782 cloning attempts, but only one – a hybrid of a goat and a different species of ibex – brought the pregnancy to full term. Unfortunately, that baby ibex had a lung defect and survived only for several minutes after birth in 2003. To date, however, this represents the only example of a resurrected animal to actually be born.

The bucardo project was led by scientists from Spain and France, who saw funding for the project dry up after that first bucardo clone died shortly after birth. The project has been revived at some level beginning in 2013 with new funding from the Aragon Hunting Federation. But there have been no new reports of successful de-extinction. In some sense, bucardos represented a best case for de-extinction, because the animal went extinct only recently, living tissue was preserved, and its habitat still exists in the same state where the animals previously thrived. However, a simpler solution to the biodiversity problem was found in 2014 when another subspecies of ibex was introduced into the French Pyrenees. The newly introduced ibex now seem to be developing features similar to the bucardo’s with each new generation, as they adapt genetically and epigenetically to the same habitat in which the bucardos previously thrived. Now the challenge will be to limit human hunting of this adapting species.

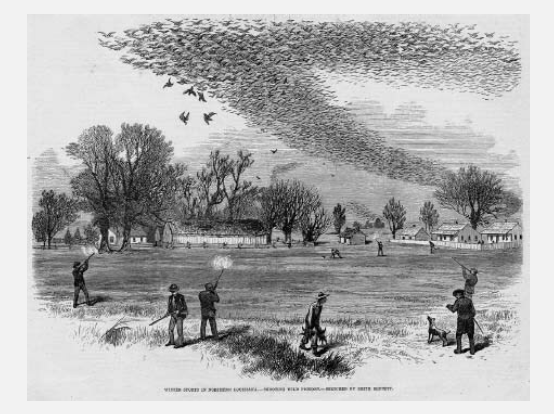

Passenger pigeon:

Passenger pigeons once numbered in the billions in the eastern and midwestern United States and often blackened the skies when enormous flocks went on their seasonal migrations (see Fig. IV.2). M.C. O’Connor notes that Alexander Wilson, a Scottish poet who emigrated to America near the end of the 18th century, wrote of an astonishing event he witnessed near Shelbyville, Kentucky when a flock of passenger pigeons he estimated to contain 2 billion birds took hours to fly over him. This used to be a common sighting in America. The pigeons often descended en masse to build nests and find food in a forest. O’Connor: “The largest nesting on record took place in 1871 in central Wisconsin where flocks congregated over 850 square miles…As many as 100,000 people traveled to Wisconsin to kill the birds for food and sport…By 1899, the last passenger pigeon in Wisconsin was shot. By 1914 there was only one known surviving bird of the species, and she died at the Cincinnati Zoo.”

Passenger pigeons seem to have been a species that relied on the sheer numbers of birds in their flocks for protection against most predators and for efficiency in finding mates and food. Hence, it is likely that humans did not kill all the birds, but rather enough to bring the species below a threshold abundance, where their numbers were no longer sufficient for their long-term survival. This is an illustration of something called the Allee effect, which argues that below a threshold density the individual fitness of members of some species deteriorates. This would make the passenger pigeon an odd choice for de-extinction since one would have to revive a large number of birds for the species to have a chance to become self-sustaining. In addition, farmers used to view passenger pigeons as pests who destroyed some of their crops; they might well be inclined to hunt the birds again unless they are then protected under endangered species laws.

Nonetheless, passenger pigeon de-extinction was one of the very first projects backed by Revive & Restore. Part of the argument for this particular project is that the passenger pigeon “quite possibly is the most important species for the future of conserving the woodland biodiversity of the eastern United States,” because the historically huge passenger pigeon flocks provided essential disturbances in the canopy of America’s forests. The de-extinction plan is to use parts of the passenger pigeon genome to edit the DNA in primordial germ cells extracted from and then injected back into the related band-tailed pigeon embryos, using the method outlined for birds in Section III. When those band-tailed pigeon chicks mature to have their own chicks, the new chicks will be part band-tailed and part passenger pigeon. The passenger pigeon DNA is being sequenced in Beth Shapiro’s lab at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

There is even a proposal “to teach resurrected passenger pigeons how to find food. [Ben Novak] proposed painting hundreds or thousands of homing pigeons so that they looked like passenger pigeons and training these painted homing pigeons to fly over the breeding colonies [of resurrected band-tailed/passenger pigeons]. These ‘surrogate flocks,’ as he called them, would attract the attention of the fledglings, who would follow their instincts and join the flocks. The surrogate flocks would ferry the young passenger pigeons between feeding sites that Ben intended to set up across the northeastern United States.” The challenge will remain to revive and breed sufficient numbers of the passenger pigeon-like birds sufficiently quickly that they reach a self-sustaining density before they die out all over again.

Woolly mammoth:

The woolly mammoth (Fig. IV.3) has clearly been extinct far longer than bucardos or passenger pigeons. They lived during the Pleistocene epoch and evolved to adapt to Ice Age conditions across northern North America and Eurasia, areas covered in ice sheets some 20,000 years ago. Compared to modern elephants they had much thicker fur, shorter ears and tail to minimize frostbite, and longer tusks which curved toward each other to avoid the excessive tipping torques that such heavy tusks would have caused if they angled further away from the animal’s central axis. In addition, they must have had genetic adaptations to increase oxygen flow within their red blood cells and to affect their metabolism, in order to survive in such cold conditions. They coexisted with early humans who occasionally depicted mammoths in cave drawings and who hunted the mammoths for food and for bones and tusks they could use to make tools, dwellings, and even for making artworks.

Most woolly mammoths went extinct about 10,000 years ago, except for small, isolated tribes on a couple of islands that lasted several millennia longer. Ancient DNA analyses of the last band of mammoths on tiny Wrangel Island just north of the Siberian coast reveals that they may have succumbed eventually to a lack of genetic diversity, an issue that often plagues small surviving populations of endangered species. Along with a number of other late Pleistocene animals that populated the northern steppes – woolly rhinoceros, Arctic fox, cave lion – the main populations of woolly mammoths presumably succumbed both to human hunting and to climate change arising from deglaciation at the end of the Ice Age.

But as noted earlier there are ample woolly mammoth remains, including mummies of essentially entire animals (see Fig. III.2), that have been discovered, especially in thawing Siberian permafrost. From such remains an extensive, though still incomplete, mapping of the woolly mammoth genome was performed in 2008. As discussed in Section III, the DNA from such ancient remains is both highly fragmented and contaminated with DNA from invading species. The team of scientists from Penn State University who sequenced the mammoth DNA “used a draft version of the African elephant’s genome [whose sequencing was then in progress]…to distinguish those sequences that truly belong to the mammoth from possible contaminants. Only after the genome of the African elephant has been completed will we be able to make a final assessment about how much of the full woolly-mammoth genome we have sequenced.”

Because there are no preserved living mammoth cells, it is not possible to clone woolly mammoths. Rather, the focus of George Church and Colossal Biosciences is to inject some critical genetic features of woolly mammoths – ones that allowed them to adapt to Ice Age cold – into egg cells taken from their nearest living relatives, the Asian elephants. In 2024 they have reached the challenging milestone of extracting induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from Asian elephant somatic cells. The next stage is to use CRISPR-Cas9 to edit the DNA in those iPSCs to replace some Asian elephant genes with woolly mammoth genes that the team guesses are most important for adaptation to cold environments. But they intend to go further than this and to also engineer other genes to give their targeted mammoth-like elephants “higher levels of adaptability to a warming planet. By de-extincting the core genes and engineering the physical characteristics of a lineage lost to extinction, Colossal will equip species with enhanced adaptability to new climates, drought tolerance and resilience against disease.” The edited iPSCs will then be injected into Asian elephant egg cells to create embryos of the new species, which undergo gestation either within the wombs of Asian elephants or, if parallel research succeeds, in artificial wombs designed for the purpose.

The Colossal research program is veering from de-extinction to species design. The stated goal of their designs is to raise, breed, and release their engineered mammoth-like elephants into the wild in Sergey Zimov’s Pleistocene Park and other protected northern reserves where they can “invigorate” the tundra. Zimov argues that “Large herbivores play different ecological roles within a community than do smaller herbivores. Large herbivores knock down trees and trample bushes, for example, and transport seeds and nutrients over much longer distances than small herbivores can.” The hope is that revived mammoth-like elephants can help to “transform a mostly barren tundra into a rich grassland,” where the revived species will graze. An added conceivable benefit would be to moderate the dangerous thawing of the permafrost caused by ongoing global warming. Under present conditions the permafrost does not cool much in winter months, even though the Siberian air is frigid, because the permafrost is insulated by a thick top blanket of snow. But the re-introduction of large herbivores would trample the snow and cool the permafrost underneath.

The goal of using de-extinction to help restore ecosystems is noble although risky. For real impact beyond a demonstration of proof-of-principle, the revived species would have to be spread wide throughout the tundra and the permafrost, beyond protected preserves. What then would prevent poachers from killing the animals for their coveted ivory? Perhaps these are issues to be addressed later. But it is difficult to avoid the feeling from the Colossal Biosciences website that the team is too enamored of their technical prowess and their belief they will transform the world. They bring to mind the hubris in a quote from the fictional film director Eli Cross, played by Peter O’Toole in the 1980 movie The Stunt Man: “If God could do the tricks that we can do he’d be a happy man.”

Aurochs:

The aurochs (Fig. IV.4) was a large, muscular herbivore ancestor of today’s domesticated cattle. It was a Pleistocene contemporary of woolly mammoths but survived in abundance in Europe until the Middle Ages. Aurochs were common objects depicted in European cave drawings. Then overhunting by nobility and loss of habitat caused the numbers of aurochs to dwindle until the last wild one died in the early 17th century. However, there is interest in Europe, led by a non-profit organization called Rewilding Europe, in re-introducing wilderness areas and their ecosystems on the continent. As part of those efforts, they have worked to save endangered species such as the European bison and the Iberian lynx. In addition, they are partnering with groups aiming to recreate aurochs, or at least cattle that share many of their physical features.

The idea that aurochs might be re-created by back-breeding from modern cattle that most resembled some aurochs features was already apparent to the Nazis in the early 1930s. Hermann Göring, who envied hunting the same prey as ancient Roman hunters, instructed the brothers Heinz and Lutz Heck, directors of German zoos, to recreate the aurochs. Heinz Heck’s efforts succeeded in breeding a more primitive-looking breed now known as Heck cattle, and these have already been introduced in nature preserves throughout Europe. But the Heck cattle are smaller, less muscular, and of different shape than aurochs. More modern efforts to get closer to aurochs features are cross-breeding Heck cattle with other types that share some aurochs-like physical features. Two such European programs, the Taurus Project and the similar-sounding but distinct Tauros Programme, have so far produced the aurochs wanna-be’s shown in the lower frames of Fig. IV.4.The competing Uruz Project seeks to accelerate the back-breeding process, i.e., to require fewer generations of breeding to get aurochs-like animals, by supplementing the breeding with gene editing based on the reconstructed aurochs genome.

Are Heck, Taurus, and Tauros cattle in wilderness areas not enough to make the rewilded ecosystems thrive? Perhaps. But the argument to continue working toward the aurochs is similar to the argument made above for woolly mammoths, emphasizing the unique role played by large herbivores in helping to re-establish healthy grasslands. In principle such a project might succeed, so long as humans do not, once again, hunt them to extinction.

Tasmanian tiger:

As is clear from Fig. IV.5, the Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, is not a member of the cat family at all. It is a carnivorous marsupial that looks rather like a dog or wolf with some tiger stripes. It was once native to Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea, but appears to have vanished from the Australian mainland some 3,000 years ago. It survived into the 20th century, however, on Tasmania, until farmers trying to protect their livestock hunted it to extinction. It was officially declared extinct in 1982. Before the species went extinct, 13 thylacine babies were taken from their mother’s pouches and preserved in ethanol. Thylacine DNA was remarkably well preserved in one of those babies and has been sequenced by a team led by Andrew Pask of the University of Melbourne, using as a template the genome of the Tasmanian devil – a still extant carnivorous marsupial confined to Tasmania, but recently reintroduced in Australia. The Tasmanian devils, by the way, are suffering from an aggressive, transmissible cancer known as devil facial tumour disease, highlighting the possibility that resurrected species may themselves be subject to diseases they had not contracted before their extinction.

The thylacine may resemble a dog or wolf, but its closest living genetic relative species may be a type of mouse, the fat-tailed dunnart – a mouse-like marsupial found throughout Australia that belongs to the same phylogenetic family (Dasyuridae) as the thylacine. Beginning in 2022, Pask’s research team has partnered with Colossal Biosciences on a project to revive the thylacine by gene-editing egg cells drawn from dunnarts to produce thylacine-like embryos. The fat-tailed dunnart will need help from “marsupial assisted reproductive technology” to serve as surrogate mothers to the much larger thylacine. The Colossal team argues that ecosystems in which the thylacine once thrived have been seriously disrupted by the extinction of their apex predator, i.e., the top of the food chain. Finding wild reserves, particularly in Australia, where revived thylacine can be reintroduced without once again being seen as pests by farmers will be somewhat analogous to the attempts we described in Section II to save the endangered gray wolves.

Other de-extinction targets:

The technology options outlined in Section III are, in principle, applicable to any extinct species for which there is reasonable DNA sequencing and genetically similar living species. While the specific animals discussed above are those for which there are recent or ongoing serious attempts at de-extinction, a number of other species are under consideration. We mention some of them here:

- The dodo, a large, flightless bird once endemic to Mauritius. It went extinct around 1700 and has a close living relative species in Nicobar pigeons.

- The little bush moa, a New Zealand bird that went extinct 500-600 years ago, after the Māori people arrived. Its genome has by now been mostly sequenced.

- The cave lion, steppe bison, and woolly rhinoceros, three of the Pleistocene contemporaries of woolly mammoths in near-Arctic steppes. Revived species would presumably be released into Pleistocene Park in Siberia.

- The Christmas Island rat, which succumbed around the turn of the 20th century to disease inadvertently brought with a human exploration expedition in the late 19th century. It is genetically similar to the living brown rat.

And what of Neanderthals, whose genome sequencing led to the 2022 Nobel Prize for Svante Pääbo? When the Neanderthal sequencing was completed in 2009, George Church opined that the technology he was pursuing could, indeed, recreate Neanderthals (using chimpanzees rather than humans as egg donors and surrogates) and that this might “satisfy the human desire to communicate with other intelligences.” Church said he had no plans to revive Neanderthals but “might go along with it” if someone else provided the necessary funding. This idea prompted Pääbo himself to pen a New York Times op-ed in 2014 entitled “Neanderthals Are People, Too.” In the op-ed Pääbo argued that “Neanderthals were sentient human beings, after all. In a civilized society, we would never create a human being in order to satisfy scientific curiosity. From an ethical perspective it must be condemned.” Beth Shapiro puts it this way: “de-extinction for the purposes of alleviating guilt seems remarkably selfish; what kind of existence would [Neanderthals]…have in the world today?”

There are currently no active programs to resurrect Neanderthals. But the arguments against de-extinction merely “to satisfy scientific curiosity” or “for the purposes of alleviating guilt” must apply to all animal species, not only hominins. It seems to us that these motivations do form a part of the inspiration, along with the allure for scientists of “technically sweet” pursuits, for most of the ongoing de-extinction projects. The public relations argument that the efforts are aimed mostly at restoring ecosystems are not wholly convincing, because the impacts on ecosystems – many of which simply no longer exist or have changed radically since the species went extinct – do not come across as seriously thought through. Nor do considerations of removing threats – including ones to which ancient species may never have been subjected – that might drive resurrected species back to extinction again.

V. when is de-extinction worth pursuing?

Just as genetic diversity is crucial for a species, so that they can sample genetic variations that may optimize adaptation to changing environments, biodiversity is essential for the health of ecosystems in which each resident species plays a role. The ongoing loss of biodiversity on Earth, attributable largely to humans taking over natural habitats, polluting the environment, and altering the climate, is alarming. Efforts to save endangered species such as those we covered in Section II are very important, even if they are not always successful.

Endangered species that succumb to extinction, but whose habitat remains more or less intact, can be revived using today’s biotechnology. A crucial step is collecting tissue samples from living members of the species and preserving them in cryogenic storage. For example, the San Diego Zoo hosts the Frozen Zoo, under the leadership of conservation geneticist Oliver Ryder. The Frozen Zoo currently contains in cryogenic storage over 10,000 living cell cultures representing about 1,000 distinct species. Among those preserved cells are sperm and egg cells that can be inseminated via in vitro fertilization. If members of the species are still alive, the resulting embryos can undergo gestation in the womb of a living female of the same species. The resulting birth can help to increase the genetic diversity of a dwindling species. For example, southern white rhino egg cells have been fertilized with sperm frozen for 20 years.

Using the technology we covered in Section III, even preserved somatic cells can be converted to induced pluripotent stem cells that can be injected, in a cloning-like procedure, into the nucleus of an unfertilized egg cell extracted from a living female of the same species or of a closely related species. If the resulting embryo can undergo successful gestation within the womb of a surrogate mother, it will lead to a birth that adds genetic diversity to a dwindling species, rescues a species on the brink of extinction, or revives a recently extinct species. These applications of the de-extinction technology we have outlined in earlier sections are praiseworthy as they work to increase biodiversity in existing ecosystems. Revived species that went extinct only recently will presumably still be covered by endangered species legal protections. However, the inefficient high-tech solution may not always be the best one. As we saw in Section IV in the case of the Pyrenean ibex, maintaining biodiversity within forests in the Pyrenées may be accomplished instead by introducing a related living ibex species and allowing it to adapt to its new habitat over a few generations.

We are more skeptical of the headline-grabbing research to revive ancient species like the woolly mammoth or its Pleistocene contemporaries. The habitat in which they originally thrived is hardly recognizable in today’s warming world. When ecosystems have evolved over millennia since a species lived on Earth, it is risky to bet that de-extinction will produce animals that thrive and advance the evolved ecosystem, as opposed to just serving as curiosities to attract tourism or prove the technical prowess of the revivers. Woolly mammoth de-extinction has been advertised as essential to transform Siberian tundra and mitigate permafrost thawing, but it is far from clear that the goal could not be reached with living species. Beth Shapiro notes that: “Working within the boundaries of his Pleistocene Park over the past few years, Sergey Zimov has [already] shown how large herbivores – bison, muskox, horses, and several species of deer – can transform a mostly barren tundra into a rich grassland over the course of only a few seasons.”

There are certainly ethical issues surrounding de-extinction of ancient species. Are the scientists involved exhibiting excessive hubris or “playing God”? Does their work and the attention (as well as possible future funding) it gets distract from the far larger efforts to save currently endangered species? Will de-extinction scientists commit as much time and energy to training and protecting any animals they revive as they do to advancing the “technically sweet” biotechnology they need? How would recovered species be altered by changes from natural breeding and social contexts? How would resurrected, genetically modified, species be treated by laws, e.g., as GMOs, or endangered species, or subject to protections from hunting by humans, or confinement to specified preserves, or benign neglect? Will revived species succumb soon enough to re-extinction? But these are not yet urgent public policy issues as the ongoing de-extinction research is largely underwritten by private funds and it will take at least several more years to even demonstrate proof of principle. The technology is fascinating but the dangers of hubris are real.

references:

Beth Shapiro, How to Clone a Mammoth (Princeton University Press, 2020), https://www.amazon.com/How-Clone-Mammoth-Science-Extinction/dp/0691157057/

M.R. O’Connor, Resurrection Science (St. Martin’s Press, 2015), https://www.amazon.com/Resurrection-Science-Conservation-Extinction-Precarious/dp/113727929X

Wikipedia, De-extinction, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De-extinction

World Wildlife Fund, What is the Sixth Mass Extinction and What Can We Do About It?, https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/what-is-the-sixth-mass-extinction-and-what-can-we-do-about-it

MedlinePlus, What is Epigenetics?, https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/howgeneswork/epigenome/

R.J. Safran, Speciation: The Origin of New Species, Nature Education Knowledge 3, 17 (2012), https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/speciation-the-origin-of-new-species-26230527/

Smithsonian Human Origins, Ancient DNA and Neanderthals, https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/genetics/ancient-dna-and-neanderthals

Amphibiaweb, Amphibian Species by the Numbers, https://amphibiaweb.org/amphibian/speciesnums.html

Wikipedia, Extinction, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extinction

National Geographic, Mass Extinctions, https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/mass-extinctions/

S. Callegard, et al., Recurring Volcanic Winters During the Latest Cretaceous: Sulfur and Fluorine Budgets of Deccan Traps Lavas, Science Advances 9, eadg8284 (2023), https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adg8284

T. Begum, What is Mass Extinction, and Are We Facing a Sixth One?, Feb. 21, 2023, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/what-is-mass-extinction-and-are-we-facing-a-sixth-one.html

Wikipedia, Baiji, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baiji

DebunkingDenial, Climate Tipping Points: Coming Soon to a Planet Near You?, https://debunkingdenial.com/climate-tipping-points-coming-soon-to-a-planet-near-you/

Wikipedia, Dolly (sheep), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolly_(sheep)

National Museums Scotland, Dolly the Sheep, https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/natural-sciences/dolly-the-sheep/

Wikipedia, Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Induced_pluripotent_stem_cell

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2012, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2012/summary/

Wikipedia, Ancient DNA, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_DNA

Wikipedia, Jennifer Doudna, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jennifer_Doudna

Wikipedia, Emmanuelle Charpentier, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emmanuelle_Charpentier

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2020, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2020/summary/

DebunkingDenial, The CRISPR Arms Race, https://debunkingdenial.com/the-crispr-arms-race-part-i/

Wikipedia, George Church (geneticist), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Church_(geneticist)

Wikipedia, Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wyss_Institute_for_Biologically_Inspired_Engineering

R. Stein, Scientists Take a Step Closer to Resurrecting the Woolly Mammoth, NPR, March 6, 2024, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2024/03/06/1235944741/resurrecting-woolly-mammoth-extinction

Wikipedia, Pleistocene, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pleistocene

Wikipedia, Sergey Zimov, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sergey_Zimov

Wikipedia, Mauricio Antón, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mauricio_Ant%C3%B3n

M. Zargar, S. Dehdashti, M. Najafian, and P.M. Choghakabodi, Pregnancy Outcomes Following in vitro Fertilization Using Fresh or Frozen Embryo Transfer, JBRA Assisted Reproduction 25, 570 (2021), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8489809/

Revive & Restore, https://reviverestore.org/

Wikipedia, Stewart Brand, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stewart_Brand

Wikipedia, Whole Earth Catalog, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whole_Earth_Catalog

Wikiquote, Robert Oppenheimer, https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Robert_Oppenheimer

Wikipedia, Manhattan Project, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manhattan_Project

DebunkingDenial, Scientific Tipping Points: The Banning of DDT, https://debunkingdenial.com/scientific-tipping-points-the-banning-of-ddt-part-i/

Wikipedia, Whooping Crane, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whooping_crane

International Recovery Plan: Whooping Crane, https://savingcranes.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/whooping_crane_recovery_plan.pdf

International Crane Foundation, Saving a Species, https://savingcranes.org/learn/species-field-guide/whooping-crane/saving-a-species/

International Crane Foundation, Raising Cranes, https://savingcranes.org/learn/species-field-guide/whooping-crane/raising-cranes/

Wikipedia, California Condor, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_condor

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, California Condor, https://www.fws.gov/species/california-condor-gymnogyps-californianus

Cornell Lab, California Condor, https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/California_Condor/overview

Wikipedia, Wolf Reintroduction, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolf_reintroduction

World Population Review, Gray Wolf Population by Country 2024, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/gray-wolf-population-by-country

The Humane Society, Legal Action Launched to Protect Wolves in Northern Rocky Mountains, Feb. 7, 2024, https://www.humanesociety.org/news/legal-action-launched-protect-wolves-northern-rocky-mountains

T. Williams, America’s New War on Wolves and Why It Must Be Stopped, Yale Environment 360, Feb. 17, 2022, https://e360.yale.edu/features/americas-new-war-on-wolves-and-why-it-must-be-stopped

K. Shepherd, Montana’s Governor Broke Rules to Kill a Yellowstone Wolf. A State Agency Gave Him a Warning, Washington Post, March 24, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/03/24/montana-greg-gianforte-wolf/

Protections for Gray Wolves Restored Across Much of the U.S., NPR, Feb. 10, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/02/10/1079965463/protections-for-gray-wolves-restored-across-much-of-the-u-s

Defenders of Wildlife, Livestock and Wolves, https://www.defenders.org/sites/default/files/publications/livestock_and_wolves.pdf

K. Almond, Just Two Northern White Rhinos are Left on Earth. A New Breakthrough Offers Hope, CNN, Jan. 27, 2024, https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2024/01/world/rhino-ivf-pregnancy-scn-cnnphotos/

Brittanica, Cloning, https://www.britannica.com/science/cloning

Frozen Zoo, https://science.sandiegozoo.org/resources/frozen-zoo%C2%AE

Wikipedia, Pyrenean Ibex, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyrenean_ibex

Wikipedia, Yuka (mammoth), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuka_%28mammoth%29

E. Jozuka, The 90-Year-Old Japanese Scientist Still Dreaming of Resurrecting a Woolly Mammoth, CNN, March 18, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/03/18/health/japan-woolly-mammoth-resurrection-intl/index.html

Colossal Biosciences, https://colossal.com/

M. Shi, et al., Haplotype-Resolved Chromosome-Scale Genomes of the Asian and African Savannah Elephants, Scientific Data 11, Article #63 (2024), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-023-02729-4

Wikipedia, Svante Pääbo, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Svante_P%C3%A4%C3%A4bo

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2022, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2022/paabo/facts/

B. Liu, A. Saber, and H.J. Haisma, CRISPR/Cas9: A Powerful Tool for Identification of New Targets for Cancer Treatment, Drug Discovery Today 24, 955 (2019), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1359644618305245

A. Regolado, Genome Engineers Made More Than 13,000 CRISPR Edits in a Single Cell, MIT Technology Review, March 26, 2019, https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/03/26/103248/genome-engineers-made-more-than-13000-crispr-edits-in-a-single-cell/

J.M. Topp Hunt, C.A. Samson, A. du Rand, and H.M. Sheppard, Unintended CRISPR-Cas9 Editing Outcomes: A Review of the Detection and Prevalence of Structural Variants Generated by Gene-Editing in Human Cells, Human Genetics 142, 705 (2023), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10182114/

Wikipedia, Steller’s Sea Cow, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steller’s_sea_cow

Wikipedia, Dugong, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dugong

T. Hildebrandt, et al., Foetal Age Determination and Development in Elephants, Proceedings of the Royal Society in Biological Sciences 274, 323 (2007), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1702383/

DebunkingDenial, Still Relevant After All These Years, Part II: Brave New World, https://debunkingdenial.com/still-relevant-after-all-these-years-part-ii/

R. Stein, An Artificial Womb Could Build a Bridge to Health for Premature Babies, NPR, April 12, 2024, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2024/04/12/1241895501/artificial-womb-premature-birth

E.A. Partridge, et al., An Extra-Uterine System to Physiologically Support the Extreme Premature Lamb, Nature Communications 8, Article #15112 (2017), https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms15112

M. Yeomans, Woolly Mammoth De-extinction Project Underway in Dallas, NBCDFW, Nov. 14, 2023, https://www.nbcdfw.com/news/local/woolly-mammoth-de-extinction-project-underway-in-dallas/3387516/

Colossal Labs, https://colossal.com/labs/

Wikipedia, Breeding Back, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breeding_back

Wikipedia, Aurochs, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aurochs

Wikipedia, Quagga, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quagga

P. Rincon, Fresh Effort to Clone Extinct Animal, BBC News, Nov. 22, 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-25052233

A. Searle, Spectral Ecologies: De/Extinction in the Pyrenees, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47, 167 (2022), https://rgs-ibg.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tran.12478

Wikipedia, Allee Effect, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allee_effect

Revive & Restore, Passenger Pigeon Project, https://reviverestore.org/about-the-passenger-pigeon/

Wikipedia, Woolly Mammoth, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woolly_mammoth

C. Zimmer, The Last Stand of the Woolly Mammoths, New York Times, June 27, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/27/science/mammoth-genes-wrangel.html

Woolly Mammoth Genome Sequenced, Science News, Nov. 20, 2008, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/11/081119140712.htm

Colossal Biosciences, De-extinction, https://colossal.com/de-extinction/

Wikipedia, The Stunt Man, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Stunt_Man

Wikipedia, Rewilding Europe, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rewilding_Europe

Aurochs: Back from Extinction to Rewild Europe, https://www.mossy.earth/rewilding-knowledge/aurochs-rewilding

Wikipedia, Taurus Project, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taurus_Project

Wikipedia, Hermann Göring, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermann_G%C3%B6ring

Wikipedia, Tauros Programme, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tauros_Programme

Wikipedia, Uruz Project, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uruz_Project

S.D.E. Park, et al., A Complete Nuclear Genome Sequence from the Extinct Eurasian Wild Aurochs (Bos primigenius), in Plant & Animal Genome XXI, January 2013, https://pag.confex.com/pag/xxi/webprogram/Paper7121.html

Tasmanian Tiger Genome May Be First Step Toward De-Extinction, National Geographic, Dec. 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20171211203647/https:/news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/12/thylacine-genome-extinct-tasmanian-tiger-cloning-science/

Wikipedia, Tasmanian Devil, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tasmanian_devil

Wikipedia, Devil Facial Tumour Disease, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Devil_facial_tumour_disease

Colossal Biosciences, Thylacine, https://colossal.com/thylacine/

Wikipedia, Fat-Tailed Dunnart, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fat-tailed_dunnart

N. Wade, Scientists in Germany Draft Neanderthal Genome, New York Times, Feb. 12, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/13/science/13neanderthal.html

Svante Pääbo, Neanderthals are People, Too, New York Times op-ed, April 24, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/25/opinion/neanderthals-are-people-too.html