September 25, 2025

I: Introduction

On August 7, 2025, the Trump White House issued an Executive Order titled “Improving Oversight of Federal Grantmaking.” The order stated that decisions on grants and awards from U.S. government scientific organizations should be subject to review by the political administrators appointed by President Trump. According to the Executive Order, the purpose was to “improve the process of Federal grantmaking while ending offensive waste of tax dollars.” The Executive Order directed each science agency to “designate a senior appointee who shall be responsible for creating a process to review new funding opportunity announcements and to review discretionary grants to ensure that they are consistent with agency priorities and the national interest.” The order maintains that such a process will insure that “Discretionary awards must, where applicable, demonstrably advance the President’s policy priorities.”

So why do we call this proclamation “The Executive Order That Could Kill American Science”? The rationale behind this Executive Order came directly from Project 2025, the 2024 report issued by the Heritage Foundation that proposed a radically expanded vision of presidential powers that would grant the President unheard-of (and in many cases unconstitutional) powers formerly delegated to Congress and the courts. With respect to science and in particular climate science, Project 2025 advocated that “The Biden administration’s climate fanaticism will need a whole-of-government unwinding … the woke agenda should be reversed and scrubbed from all policy manuals, guidance documents, and agendas, and scientific excellence and innovation should be restored as the [Office of Science Technology and Policy] OSTP’s top priority.” Figure I.1 shows the cover of Project 2025. Not only has the Trump administration followed the recommendations in this document extremely closely, but a major architect of Project 2025, Russell Vought, is currently the Director of the Office of Management and Budget.

Figure I.1: Project 2025, a Heritage Foundation report published in 2024. It laid out in detail a project to radically reshape government, with the President seizing powers that had previously been delegated to Congress and the courts. The second Trump administration has closely followed this blueprint, by installing leaders at government agencies whose loyalty was to Donald Trump, rather than to the Constitution or maintaining independence from the President, as had traditionally been the case for their agencies.

The Trump Executive Order would allow senior political Trump appointees at the head of science agencies to review and deny grants and awards that had been approved by scientific peer review processes. It is not hyperbole to conclude that such reviews would end the process by which research agendas were determined by scientists. This proposed process is exactly the opposite of what Vannevar Bush, the father of the U.S. federally-supported science program, envisioned. Bush was a scientific advisor to the President when he authored the 1945 report Science: The Endless Frontier. That report suggested that the federal government fund research in science. The government would provide support to scientists and for the construction of laboratories for research. Bush was adamant that decisions about what science to support be made by scientists themselves and not the scientific administrators. Eventually his efforts led to the creation of the National Science Foundation (NSF). Figure I.2 shows a copy of Science: The Endless Frontier with a photo of Vannevar Bush. This 2020 document was released on the 75th anniversary of the founding of the NSF.

Figure I.2: Vannevar Bush and his 1945 report Science: The Endless Frontier. This special edition was reprinted in 2020 to mark the 75th anniversary of the National Science Foundation that was created as a result of Bush’s report.

The federal support for science outlined by Vannevar Bush has grown into a massive program that supports the sciences in many areas. For the past 80 years, this system has produced extraordinary achievements in physical sciences such as chemistry, physics, astronomy and geology. The life sciences have also made exceptional strides and have established the U.S. as the clear global leader in support for basic research and applied health. But the layer of political oversight outlined in Project 2025 would very likely result in calamitous outcomes for American science. Entire fields such as research in global climate change would be shut down. Areas such as vaccine research and research into HIV/AIDS could be abandoned because of the whims of politically appointed heads of science agencies. Since political priorities generally shift from one administration to the next, tying scientific research funding to political goals would undermine the reliable long-term support that has allowed many scientific fields to flourish in the U.S. since 1945.

In this post we will begin by studying the results in other countries when science was subjected to political interference. Here we will focus on the situation in Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s, when the Germans forbade Jewish scientists from occupying posts in universities, prior to rounding them up and transporting them to concentration camps. Next, we will review the situation in Stalinist Russia, where agricultural scientist Trofim Lysenko gained control of the Russian agricultural system. He then banned research and applications of genetics in favor of his favored theory where characteristics acquired during a lifetime could be passed on to future generations. In both cases, we will show that the political interference into science was a disastrous failure.

We will then review situations in the current Trump administration where scientific research is being subjected to political ideology. Like the situation with the Nazis and Stalinists, the result is likely to prove terribly damaging to American science.

II: Prior Examples of Political Interference in Science

Authoritarian regimes typically attempt to seize control of institutions that pose a threat to their rule. An independent judiciary, a free press, independent universities and other organizations are often attacked, and efforts are made to take over or otherwise thwart the ability of these organizations to operate freely. A good recent example of this is Hungary under their leader Viktor Orbán. Orbán is the leader of Fidesz, the current ruling political party. After taking power in 2010, Fidesz produced a new constitution, to which it has now added some 2,000 amendments, in the process removing checks and balances that could have restrained the government. Fidesz has been applying its right-wing populist rhetoric ever since. The government has overhauled the judiciary, replacing former incumbents with its own adherents; they have taken over nearly all media outlets, and changed election procedures. The result is a Hungarian state that is viscerally hostile to immigrants.

Science is also the source of many inconvenient truths that are opposed by repressive governments. We have seen several cases where the state imposes political constraints on scientific principles and/or individual scientists. In this section we will review the situation with two of the famous cases, Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Russia. As we will show, the results in both cases were disastrous for the countries involved.

A: Aryan Science in Nazi Germany

In Germany at the beginning of the Nazi regime, there was an attempt to create a discipline called Deutsche Physik or “Aryan Science.” This was actually an extension of an earlier nationalistic movement that appeared at the beginning of World War I. So we will first review that period and then move to the Nazi era.

At the beginning of World War I, a coalition of 93 German scientists, philosophers, theologians, artists and others composed a proclamation called Manifest der 93: An die Kulturwelt! The document, which can be found here, was a reaction to charges made by Germany’s opponents in World War I, particularly the British. Figure II.1 shows the cover of the manifesto. The manifesto had several purposes. One was to demonstrate that the German people, and particularly their scientific and philosophical leaders, were strong supporters of the German war effort. A second motive was to contest accusations that the German government had begun the war, that the German state was inherently militaristic, and that German behavior in the war to date (particularly in what was called the “rape of Belgium”), constituted war crimes by the German state. One of the events that led to the manifesto was a letter signed by eight distinguished British scientists protesting the fact that German troops had set fire to the library of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium. Manifesto 93 stated that the German people would “carry on this war to the end as a civilized nation … For this we pledge to you our names and our honor.” Signatories included Nobel Laureate scientists Adolf von Baeyer, Emil von Behring, Paul Ehrlich, Hermann Fischer, Fritz Haber, Philipp Lenard, Walther Nernst, Wilhelm Ostwald, Max Planck, Wilhelm Röntgen, Wilhelm Wien and Richard Willstätter. This represented an impressive group of scientists, who were joined by leading theologians, artists and philosophers.

The militaristic and nationalistic tendencies of the Germans would persist, particularly after the Germans were forced to accept what they saw as unfair and punitive sanctions as part of the Treaty of Versailles that followed the end of World War I and imposed harsh conditions on the German government.

Figure II.1: The Manifest of the 93: the manifesto produced in 1914 and signed by 93 German scientists, theologians, artists and politicians. It rebutted charges that the German government had started World War I, and that German military forces had committed war crimes in Belgium. The manifesto was signed by many of the most prominent scientists and theologians in Germany.

Another feature of German activities in World War I was the participation of several of the most accomplished German scientists in the war effort; in particular, Nobel Laureate Fritz Haber headed the German chemical weapons program and Otto Hahn, who would win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1944 for the discovery of nuclear fission, also worked on the German government’s chemical weapons development.

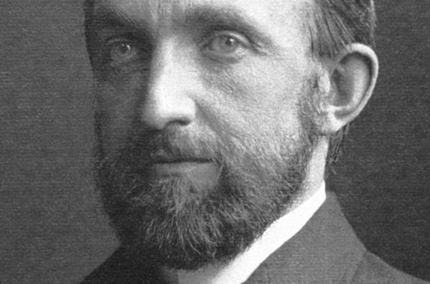

German resentment at their treatment following World War I was one of the factors that led to Adolf Hitler being installed as the Chancellor of Germany in 1933 and the subsequent transformation into the totalitarian government of Nazi Germany. Several of the scientists who had signed the Manifesto of the 93 in 1914 were also sympathetic to the Nazis. Two of the most fervent pro-Nazi scientists were the Nobel Laureates Philipp Lenard (shown in Figure II.2) and Johannes Stark (shown in Figure II.3). The two physicists were leaders of the Aryan Physics movement (called Deutsche Physik in Germany).

Figure II.2: Philipp Lenard. He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1905 for his studies of the properties of cathode rays. Lenard was a fervent nationalist and antisemite. He became a leader of the “Aryan Physics” movement in Germany.

Figure II.3: Johannes Stark. He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1919 for his discovery of the splitting of spectral lines in an electric field. Stark was a strong supporter of the Nazis and an antisemite. He became a leader of the “Aryan Physics” movement in Germany.

Figure II.4 shows the cover of a four-volume physics text by Philipp Lenard called Deutsche Physik. Despite the avid participation of several of the most influential scientists in Germany, the concepts of “Aryan Physics” were always a bit murky. A central feature of Aryan Physics was that physics should be dominated by experimental results. This was in contrast to recent developments in physics (particularly relativity theory and quantum physics) where theoretical developments had often preceded experimental verification. For example, Einstein’s 1905 theory of special relativity postulated that the speed of light was the same when measured by any observer, regardless of their velocity with respect to the light source. In addition, Einstein claimed that time was not an absolute quantity, but that its measurement changed according to the velocity of an observer. Finally, Einstein claimed that electromagnetic (EM) waves could travel through a vacuum. Prior to the special theory of relativity, it was assumed that EM waves were carried by a medium, the luminiferous ether.

Figure II.4: The physics text Deutsche Physik, a four-volume tome written by Philipp Lenard. It attempted to define “Aryan Physics” and justify it, in opposition to what Nazis called “Jewish science.”

Prior to Einstein’s special theory of relativity, scientists had been taught about the luminiferous ether and had assumed its existence throughout their careers. So there was considerable resistance towards the idea that this ether did not exist and should no longer be used. There were also critics of Einstein’s 1915 general relativity theory and its claim that light would bend when moving past a massive object, in analogy to the way that a mass would be attracted towards another mass through the gravitational force. In 1919, Arthur Eddington had confirmed a quantitative prediction of general relativity by measuring the deflection of light from a star as it traveled near the Sun; however, Aryan Physics advocates claimed that Eddington’s measurement was not conclusive. Another “proof” of the validity of general relativity, the explanation of the motion of the perihelion of Mercury, might also be explained without resorting to general relativity.

“Proofs” of special relativity, such as the result of the Michelson-Morley experiment that found the speed of light independent of its direction with respect to Earth’s orbital motion, could also be explained without invoking special relativity. As a result, there was considerable skepticism regarding Einstein’s theories. There was also widespread resistance to the precepts of quantum physics, despite the central role in its development played by the young German (and ‘Aryan’) physicist Werner Heisenberg. Many of the laws of quantum physics seemed counter-intuitive and speculative. They seemed to violate a “common sense” understanding of the laws of physics. So Aryan Physics, in general, rejected principles of relativity and quantum physics. But there was not universal agreement among “Aryan Physics” advocates on which aspects of relativity or quantum physics to adopt, and which to reject.

However, in Germany in the first half of the 20th century, another potent feature was a virulent antisemitism. There was great animosity towards the Jews, who were being blamed for virtually all of Germany’s misfortunes. Aryan Physics explicitly linked their disapproval of “speculative” physics such as relativity and quantum physics with hatred of the Jews. So Aryan Physics advocates such as Lenard and Stark, noting that Jewish scientists and Einstein, in particular, were the leaders of these new fields, labeled the objectionable science as Jewish Physics. This gave the Aryan Physics movement a powerful rallying cry: physics at German universities should be carried out by “Aryan Physicists.” In practice, this meant that Jewish (also Communist and other minority) scientists should be prohibited from holding faculty positions in German universities.

Since antisemitism was a central feature of Nazi dogma, there was a natural bond between the Aryan Physics targeting of Jews and that of the Nazi party. Initially, the two groups collaborated in campaigns to remove Jewish physicists from faculty positions in German universities. However, in 1935 the Nazis passed the Nuremberg Laws; under these laws Jews were forbidden to hold any university positions. Thus, the efforts of people like Lenard and Stark to remove Jews from university positions were no longer so helpful to the Nazis. The most serious blow to the Aryan Physics movement came in the treatment of Werner Heisenberg. Heisenberg, who won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1932 for the discovery of quantum mechanics, was a German hero. Although he worked in the “Jewish science” field of quantum physics, he was not a Jew. Nevertheless, various Aryan Physics advocates sharply criticized Heisenberg for “intuitive” theories such as the Uncertainty Principle, and for Heisenberg’s matrix mechanics. Heisenberg came under severe attack from Aryan Physics advocates; in fact, he was called a “White Jew” (i.e., an Aryan who acted like a Jew), and at one point it was suggested that he should be made to “disappear.” Eventually Heinrich Himmler, the leader of the Nazi SS, intervened and ordered the attacks on Heisenberg to cease. After this incident the Aryan Physics movement gradually lost its status; however, scientists like Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark continued to be strongly pro-Nazi.

B: Nazi Attacks on Jewish Scientists

The attacks on Jewish scientists by groups like the Aryan Physics movement were overtaken by persecution of Jews by the Nazi regime. The Nazis discriminated against many groups – Jews, those who had Jewish relations, Roma, political opponents such as Communists, the disabled and mentally ill, and homosexuals. The Nazi persecution led to the emigration of an entire generation of scientists. By 1936, Nazi discrimination against Jews forced 1,600 academics out of German universities; 500 of these were scientists. When they were able to leave the country, German Jews emigrated to different countries, with a number of German Jewish scientists making their way to the United States. Later on, as the Nazis occupied other European countries, Jewish scientists from those countries also emigrated when possible. As just one example, brilliant Hungarian scientists such as Eugene Wigner, Edward Teller, Leo Szilard, John von Neumann and Theodore von Karman all emigrated to the U.S. and made extraordinary contributions to the Manhattan Project, the field of nuclear physics, the development of the computer, and the field of aerodynamics.

The wholesale migration of talented scientists to the U.S. would completely reverse the standing of German and American science. Up to the 1930s, German science far outstripped that of the U.S. In physics, a new generation of American scientists such as J. Robert Oppenheimer and Ernest Lawrence had received training in Europe that enabled them to achieve leadership positions in the U.S. But the number and quality of European scientists who emigrated to the U.S. transformed the scientific community in this country. In an ironic twist, the European scientist emigrés played crucial leadership roles in the Manhattan Project, at the time the largest scientific project of its time, that eventually led to the production of the atomic bomb. And the physics behind the atomic bomb was the “Jewish physics” of quantum mechanics.

We will not list the many British scientists who collaborated on the Manhattan Project, but a short list of other European scientists who contributed to that project includes Enrico Fermi *, Niels Bohr *, Albert Einstein *, James Franck *, Hans Bethe **, Eugene Wigner **, Edward Teller, Leo Szilard, John von Neumann, Emilio Segre **, Felix Bloch **, Otto Frisch, Samuel Goudsmit, Klaus Fuchs, Rudolf Peierls, Joseph Rotblat **, Stanislaw Ulam, and Victor Weisskopf (in this list, an asterisk denotes scientists who received the Nobel Prize before they emigrated, while a double asterisk denotes those who received a Nobel Prize after they emigrated to the U.S.).

On the Manhattan Project, the brilliant and accomplished European scientists were paired with a young generation of American scientists who quickly became world scientific leaders in their own right. Arthur Compton *, Ernest Lawrence *, Robert Oppenheimer, Glenn Seaborg **, Robert Serber and others were the more senior of the group, while younger scientists such as Richard Feynman ** and Luis Alvarez ** made important contributions to this effort. The combination of European excellence with the less hierarchical and more open American style, together with sources of rapid and generous funding, produced an atmosphere that led to extremely rapid progress. Figure II.5 shows a group of physicists who produced the “atomic pile,” the world’s first sustained nuclear chain reaction, at the University of Chicago in 1942. Enrico Fermi is at left in the first row, while Leo Szilard is on the right in the second row.

Figure II.5: Scientists who worked on the “atomic pile” at the University of Chicago; this was the first sustained nuclear chain reaction. Enrico Fermi is on the left in the first row, while Leo Szilard is on the right in the second row.

The European emigration that transformed American science had, conversely, the opposite effect on German science. At the start of the Manhattan Project, Germany had a significant lead on the Allied powers in the area of nuclear physics. Nuclear fission had been discovered by Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner and collaborators, and quantum physics was dominated by Heisenberg, Hilbert and other Germans. In fact, the German lead in this area was the subject of the famous letter to President Roosevelt composed by Leo Szilard and signed by Albert Einstein, pointing out the fact that nuclear fission had the potential to produce immensely deadly weapons, and that the Germans were far ahead of the Allies.

However, the loss of all the emigrated scientists made it extremely difficult for the Germans to pursue the construction of an atomic bomb. In her 1968 book Illustrious Immigrants: The Intellectual Migration from Europe 1930-41, Fermi’s wife Laura Fermi puts it this way: “European nations did not have the money, the broad vision, or the faith that were required, nor did they have the concentration of brain power. Its best brains had emigrated.” The German effort was further hampered by the fact that Werner Heisenberg, who was the scientific leader of the secret Nazi nuclear program, made a significant error. Heisenberg made a rough calculation of the fissile material needed to produce a chain reaction bomb; however, he estimated that an atomic bomb would require tons of Uranium 235 (U-235), whereas the correct number was only pounds of U-235. Partly as a result of his mistake, Heisenberg did not push as hard for development of a bomb as did the Allies.

In any case, the Nazi persecution of the Jews and others caused many scientists to emigrate. This devastated German science immediately before World War II. While the U.S. and Allied powers benefited enormously from the infusion of European emigrés, after World War II German science never fully recovered its position of supremacy in the physical sciences. The lead in science had passed to the United States. From the end of World War II to the present, the U.S. has been the leader in science. As we noted earlier, this era began with the famous report Science: The Endless Frontier, authored in 1945 by Vannevar Bush. Bush envisioned an American science effort that combined significant government support with universities and research labs that awarded merit and avoided political interference. For the past 80 years, this system has produced scientific results that have often led the rest of the world. The supremacy of politics over science proved disastrous to the Germans, destroying their scientific establishment. It is critical that such political interference not be allowed to demolish the American science effort.

C: Lysenkoism in the Soviet Union

Charles Darwin’s hypotheses regarding evolution introduced a new field of science. However, Darwin was not aware of the process by which natural selection occurred, so a major thrust of biology in the latter half of the 19th century involved the search for the mechanism behind reproduction and natural selection. Led by scientists like Thomas Huxley and Thomas Hunt Morgan, and influenced by the re-discovery of the plant breeding experiments of Gregor Mendel, the field of Mendelian genetics was developed. In this theory, the characteristics of an organism are determined by genes, which are located on chromosomes that reside in the nucleus of each cell. In the process of sexual reproduction, chromosomes from male and female parents are combined and their genes are passed on to the next generation. Genes can be altered by random mutations during reproduction, but they remain largely unaltered throughout an organism’s life. In particular, characteristics that are acquired in the lifetime of an individual are almost never passed on to a subsequent generation.

A given population will have a distribution of various characteristics. As an example, the amount of hair on the body of an individual can vary. For a primitive tribe, if their ecosystem is going through an Ice Age, natural selection will give preference to individuals that have a large amount of body hair, relative to people with almost no body hair. In this way, the majority of the population will eventually end up with large amounts of body hair. In agriculture, changes in the properties of a plant can be affected through selective breeding. The re-discovery of the plant breeding experiments in the 1860s by the Austrian friar Gregor Mendel showed how different genes were expressed in cross-breeding experiments.

By the 1930s, the laws of genetics were being tested in laboratories around the world. It had been demonstrated conclusively that the Lamarckian theory of reproduction, which stated that parent organisms passed on to future generations characteristics that were obtained during their lifetime, failed to provide a satisfactory explanation of reproduction. The germ plasm theory of August Weissmann stated that the material that determines the transmission of inherited properties resides in the reproductive organs. The new generation develops its own somatic cells from the germ plasm. Any changes acquired during the lifetime of the organism have no effect on the germ plasm (i.e., sperm or egg cells). If Weissmann’s theory is correct, then Lamarckism is bound to fail.

However, the Soviet biologist and agricultural scientist Trofim Lysenko became a firm opponent of the field of genetics, and a believer in the Lamarckian hypothesis that acquired characteristics could be passed along to future generations. Figure II.6 shows Lysenko inspecting samples of wheat grown at his experimental farm. Lysenko’s rise to power began in 1927 when he observed that when peas were kept at low temperatures, their seeds germinated faster than at room temperature. He mistakenly concluded that when subjected to extreme conditions, the peas transformed themselves into a different species. He then went on to apply extremes of heat, cold or humidity to various species of plants, and he convinced himself that this ‘conditioning’ could induce plants to transform themselves into new species.

Figure II.6: Plant scientist Trofim Lysenko, at right, examining samples of wheat grown on his experimental farm.

Lysenko also employed a political argument to explain why Lamarckian theory was more compatible with Marxism than Mendelian genetics. Marxist theory stated that man was a product of his own will; man thus had the capability of transforming himself, and according to the Russians he could create a “New Soviet Man.” Lysenko and his colleagues claimed to have created a “Marxist genetics” that allowed for the possibility of unlimited transformation of living organisms through environmental changes passed on via inheritance of acquired characteristics. As a result, Lysenko claimed that there was no such thing as a “clearly defined species;” he also claimed that members of the same species or ‘class’ did not compete with one another, but instead cooperated for the common good. This led him to advocate that farmers plant seeds of the same species very close together, on the notion that the resulting plants would cooperate to maximize the crop yield. This advice proved catastrophic in actual practice.

Mendelian theory said that the evolution of man and other species occurred only through random genetic mutations plus natural selection. Mendelian genetics appeared to be incompatible with Marxist doctrine; thus, Lysenko and his followers attacked genetics as being counter-revolutionary “bourgeois science.” They claimed that modern genetics was the result of a conspiracy by capitalists and other opponents of Marxism; the genetic conspiracy was supposedly created in order to favor eugenics and race theory and to reject Marxist science.

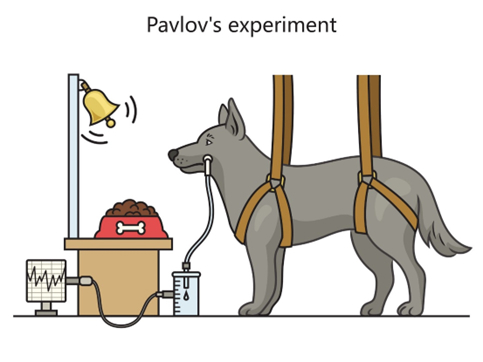

Initially, Lysenko and his supporters pointed to two experiments that seemed to support the idea that acquired characteristics were passed along to future generations. Ivan Pavlov was the discoverer of conditioned reflexes. Figure II.7 shows a cartoon of Pavlov’s experiments that demonstrated conditioned reflexes in canines. Pavlov announced in 1923 that mice conditioned using his methods could pass these acquired conditioned reflexes to subsequent generations of mice. Pavlov later retracted this claim, although it was not noticed by Lysenko and his followers. A second major influence on Lysenko was botanist Ivan Michurin. Michurin claimed that his success in plant breeding was made possible through the Lamarckian inheritance of acquired traits.

Figure II.7: A cartoon of Pavlov’s conditioned reflex experiment on canines. After a bell is rung, food is provided to the dog. After a while, the dog begins to salivate whenever the bell is rung, anticipating the food that will follow.

Lysenko next claimed that through his conditioning methods, he could transform spring wheat into winter wheat. He claimed to have planted spring wheat in the fall, and then repeated this for four years, after which time the spring wheat had transformed itself into winter wheat. Lysenko also claimed that his winter wheat could produce yields far in excess of anything yet achieved. Conventional wheat could be made to produce 2,000 kilograms of wheat per hectare (2,000 kg/ha) under the most favorable conditions. However, Lysenko promised Joseph Stalin that his conditioned wheat would produce 15,000 kg/ha. In addition, these remarkable yields were to be obtained without applying any fertilizer. Of course, these results were never achieved outside the Soviet Union. Modern genetics also stated that such a transformation was essentially impossible. Triticum durum (spring wheat) is a tetraploid (4 sets of 7 chromosomes each, leading to 28 chromosomes) while Triticum vulgare (autumn wheat) is hexaploid (6 sets of 7 chromosomes each, leading to 42 chromosomes). This did not faze Lysenko who simply claimed that his conditioning technique changed the number of chromosomes. Others of Lysenko’s supporters rejected the whole notion of genes.

Lysenko’s claim of a new variety of wheat with unheard-of yields made a significant impression on Soviet agricultural committees. During the era 1929 – 1932, Stalin had announced that all farmland would be collectively owned and operated. He identified prosperous peasants who owned and farmed their own land as “kulaks,” and in 1929 announced the “liquidation of kulaks as a class.” Nearly 2 million peasants were deported, imprisoned, made to work in labor camps, or killed as part of this campaign. Figure II.8 shows wealthy peasants or “kulaks” being evicted from their land by working-class Soviets, who would create collective farms on the land.

Figure II.8: Poster supporting ouster of wealthy peasants (“kulaks”) from their farms in the Soviet Union, in the late 1920s. The title reads “Strengthen working discipline in collective farms.”

But a result of the disruption of the farms was a dire shortage of grain, which caused a major famine in the USSR in 1932-33. Millions of people had died in the resulting famine. So Lysenko’s claims that he had produced grain that would flourish in colder climates and produce record yields were eagerly adopted. Joseph Stalin was impressed with Lysenko’s ’successes,’ and in 1938 Lysenko was named the Director of the Lenin All-Union Academy of the Agricultural Sciences. This began a systematic purge of Russian scientists who believed in Mendelian genetics. A particularly ironic casualty was Nikolai Vavilov, who had been Lysenko’s mentor and was his predecessor as Agricultural Sciences director. Vavilov attempted to point out that Lysenko’s claims were incompatible with proven features of genetics. For his efforts, Vavilov was tried and imprisoned, and died of starvation in a gulag. Approximately 3,000 scientists who advocated for modern genetics were fired, imprisoned or executed.

In 1948, the Academy of Agricultural Sciences held a session where Lysenkoism was pronounced “the only correct theory.” Science departments were directed to fire anyone who did not subscribe to “Michurinist biology.” Textbooks were withdrawn, any references to Mendelian genetics were removed, and labs were ordered to destroy all stocks of Drosophila flies (which were widely used in genetics studies).

Meanwhile, Lysenko had moved on to ever more fantastical (and phony) research claims. Among other claims, Lysenko stated that his experiments showed that some plants would voluntarily “sacrifice themselves” so that the remaining plants might flourish. For example, Lysenko advocated planting trees in close groups or “nests;” under those circumstances, the trees were said to work cooperatively so that the nest would flourish. Lysenko’s journal Agrobiology published reports of transforming wheat into rye and cabbages into rutabaga. Stalin made Lysenko a major figure in his Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature of the late 1940s. Soviet media would print propaganda such as “Siberia is transformed into a land of orchards and gardens,” and “Soviet people change nature.” Figure II.9 shows a Soviet propaganda poster hailing the tremendous agricultural breakthroughs claimed by Lysenko and his followers. As Lysenko was in charge of state agriculture, “official” government releases claimed that the production of food had reached new heights. In reality, Lysenko’s techniques had led to disastrous shortfalls in food production. In hindsight, it was relatively easy to see that Lysenko’s claims were bogus. Decades of genetics research had proved that his assertions about Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics were false.

Figure II.9: A propaganda poster celebrating the tremendous agricultural achievements in the Soviet Union that supposedly arose from Lysenko’s ‘proofs’ of the Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics.

No one outside the Soviet Union was able to reproduce Lysenko’s results of transforming one species into another through application of large changes in temperature and humidity to “condition” the species. Nor were outside researchers able to obtain anything like the crop yields claimed by Lysenko. Scientific bodies that used evidence-based experiments would invariably falsify Lysenko’s claims. This had little effect on Lysenko. He rejected controlled experiments and the use of statistical methods to test theories. Lysenko even asserted that “mathematics has no place in biology” (!) Lysenko’s claims were echoed by his supporters, and by the Russian press that replaced actual crop yield data with fictitious figures claiming “miraculous” results.

It is not clear when Lysenko’s claims turned from hype of his results to downright fraud, although this must have occurred rather early in his career. However, all of Lysenko’s failures were covered up during Stalin’s lifetime. Actual crop yields were simply falsified in government reports while Soviet citizens died of malnutrition. And researchers who dared to challenge Lysenko were subject to being fired, imprisoned or murdered; in this way any challenges to Lysenko’s claims were silenced. After 1953, when Stalin died and was replaced by Nikita Khrushchev, the situation slowly began to change. Although Lysenko was still a top administrator, geneticists who had been jailed were released, and articles advocating modern genetics began to be published in Russia. It was not until 1965 that Lysenko was terminated as director of Genetics for the Soviet Academy of Sciences.

In summary, the influence of Trofim Lysenko and his followers, from roughly 1930 until 1965, was an unmitigated disaster for the Soviet Union. Although Lysenko’s understanding of genetics was extremely limited, he claimed that modern genetics was a “bourgeois science,” the result of a conspiracy of capitalists designed to benefit race theory and eugenics. Lysenko claimed that the Lamarckian theory of inheritance of acquired characteristics was compatible with Marxist theory. He bolstered his political arguments with “demonstrations” where he subjected plants to extremes of temperature and humidity. Lysenko claimed that with these techniques, he could radically change the nature of the plants. First, he claimed that these conditioning techniques could produce record yields; following that, he claimed that he had actually converted one plant species to another.

Lysenko’s claims resonated with Soviet bureaucrats. First, he gained the attention of Joseph Stalin, who appreciated applications of Marxist theory to agriculture. Stalin also found Lysenko’s status as the son of Russian peasants attractive. Lysenko’s claims that he had converted spring wheat to winter wheat, and that he could produce unheard-of yields without the application of fertilizer, were eagerly embraced by Soviet agricultural planners. They had recently suffered through terrible famines due to the annihilation of the Russian “kulak” farm owners. The thought that Lysenko’s miracle wheat could alleviate famines and usher in a Brave New World of Soviet agriculture was irresistible to Russian bureaucrats.

There were those pesky Western scientists, who pointed out that Lamarckian theories had been conclusively falsified by modern genetics. And agronomists outside the Soviet Union invariably failed to replicate Lysenko’s claimed successes. These critiques were dealt with by Joseph Stalin’s repressive regime. Some 3,000 scientists who espoused genetics theory were dismissed, jailed or even executed by Stalin. The remaining scientists either kept their opinions to themselves, or they firmly backed Lysenko’s experimental claims (Lysenko reacted to adverse theoretical arguments by labeling them “bourgeois science,” or ignoring them altogether). Once Lysenko was installed as the head of genetics in the Soviet Union, the takeover of Soviet biology and agronomy was complete.

The only remaining obstacle was the fact that Lysenko’s agricultural methods failed miserably. His “conditioned” plants never achieved anything like the miraculous yields that he claimed, and no one could reproduce his claims of converting, say, wheat into rye or cabbages into rutabagas. Nevertheless, the Soviet system supported Lysenko for many years. Published reports spoke of magnificent yields of wheat and other staples. Lysenko’s methods were said to have converted the bleak Siberian steppes into a paradise of fruits and vegetables. The reality was extremely harsh. Instead of miraculous successes, Soviet harvests were so meager that millions of people starved. This human tragedy was an added “bonus” of the Lysenko affair; Soviet citizens died because actual crop yields were radically below the amounts claimed by the Soviets. Not only was the science suppressed, but control of the press meant that actual crop yields were never made public.

The effect on Soviet biology was stark. In just a few years, Lysenkoism produced a 50-year period where a previously thriving field of modern biology was demolished. Lysenko’s pseudo-science destroyed earlier Soviet advances in biology and agronomy. Thousands of people were fired or even executed for their beliefs, and the remaining scientists either kept silent or embraced the new pseudoscience. Genetics textbooks were withdrawn, and information that contradicted Lysenkoism was purged. Russian biology under Lysenko is a stark object lesson in how rapidly a legitimate field can be destroyed, when science is subjected to a political litmus test. Lysenko’s theories could have been tested and falsified (they were everywhere outside Russia), but under an authoritarian regime legitimate dissent can be punished, and authentic data can be purged, suppressed or replaced by propaganda. The situation with Lysenko offers a vivid picture of the result when science is subjected to a political litmus test, and when scientists are judged by their loyalty rather than by their competence and the scientific verification of their theories and purported experimental results.

— Continued in Part II —