August 8, 2024

I. introduction

This post is about the rapidly growing global resource demands of several aspects of the high-speed computing sector, in an era when the world should be focused on reducing humans’ greenhouse gas emissions and exhaustion of fresh water resources. In the words of environmental journalist Elizabeth Kolbert in a recent New Yorker article, “How can the world reach net zero if it keeps inventing new ways to consume energy?”

Let’s first put the issue in perspective by comparing to overall energy and electricity usage worldwide. In 2022 the total energy generated globally by all sources was roughly 160,000 terawatt-hours (TWh) or 160 billion megawatt-hours (MWh). To put that number in perspective, the total annual electrical energy consumption by a typical U.S. home is about 10 MWh. Less than 20% of this total was devoted to electricity production, the rest going to oil and gas for heating and gasoline in the residential, industrial, commercial, transportation and government/military sectors, or to waste.

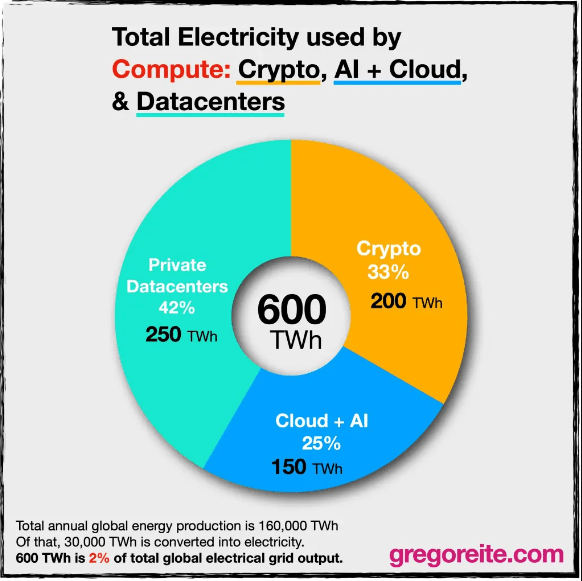

In round numbers, the total electrical energy consumed globally in 2022 was about 30,000 TWh. The approximate breakdown among energy use sectors is shown in Fig. I.1. Note that only about 2% of all global electricity usage was attributed to the commercial computational sector, primarily to operating data centers, maintaining cloud data storage, cryptocurrency mining, and the training and operation of artificial intelligence (AI) systems. The total global energy consumption by all classes of computers and computational infrastructure was more like 5% of total global electricity demand. The 5% includes: private servers and server farms; laptop and desktop computers; charging smartphones and tablets; supercomputer centers; and network hardware. So, the cyberhogs we focus on in this post are manageable for the moment. The problem is that their energy demands are growing much more rapidly than those in all other sectors, as we will explore in this post.

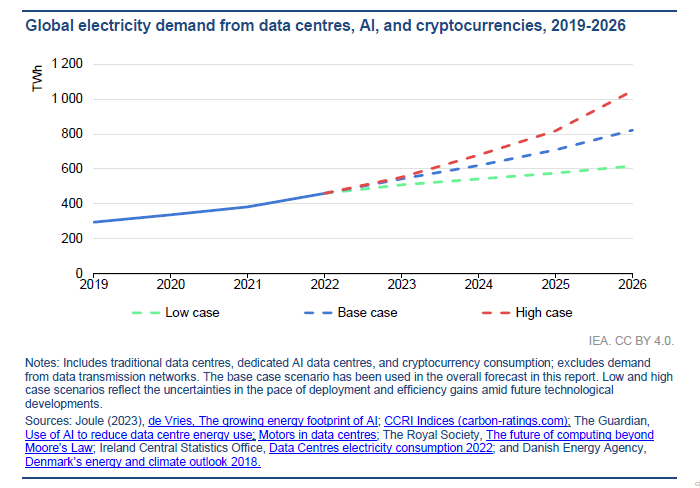

Among crypto-mining, AI, and commercial-scale cloud storage and data centers, the approximate breakdown in electricity usage for 2022 is shown in Fig. I.2. The numbers here are guesstimates because reporting of resource usage by the computer industry is sketchy, at best. But Fig. I.2 is a snapshot in time. The energy demand of the cyberhog sector – crypto-mining, AI, and commercial data centers – has been growing rapidly and is projected to continue growing rapidly – by about 50% every three years — as shown in Fig. I.3 from the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Electricity 2024 Report. By 2026 these sectors may well use 1000 TWh of electricity. In contrast, the global electricity production is growing slowly at best and that growth may be interrupted as we phase out fossil fuel plants and replace them with renewable sources.

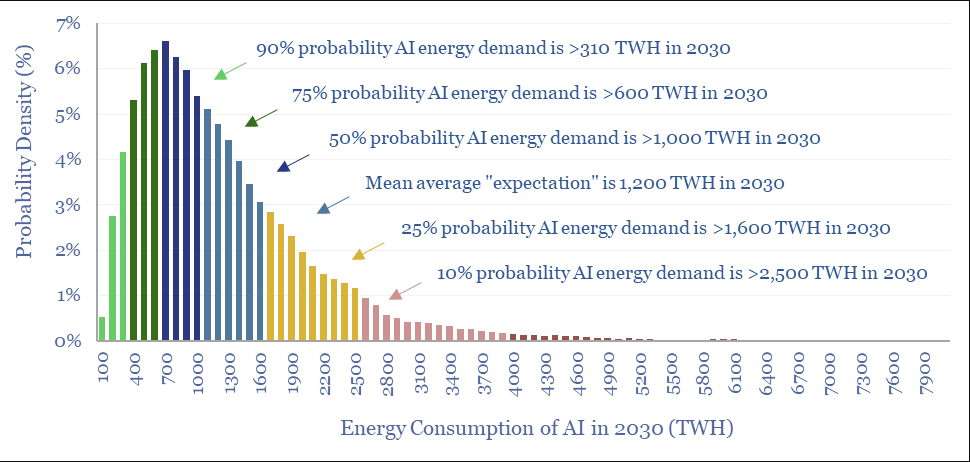

The IEA projections may well be conservative. For example, Fig. I.4 shows that half of the projections that have been made out to 2030 suggest that AI demands alone may exceed 1,000 TWh by then.

II. cryptocurrency mining

Blockchain:

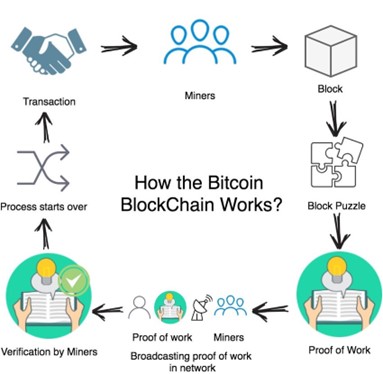

In this post we will argue that cryptocurrency, and specifically the currency Bitcoin, are employing methods that use enormous amounts of energy to run specialized computers. We will demonstrate that the amounts of energy being used are unsustainable, unless significant changes are made in the Bitcoin system. The general details of cryptocurrency were discussed in an earlier post on our blog. In that post, we reviewed the operations of the cryptocurrency system. These operations represent the steps that are taken to produce a system of currency, including all the transactions that would normally be done by banks, in a way that is transparent and involves none of the human interactions that would normally be performed by bank employees. In the cryptocurrency system, groups of transactions are added to a permanent and transparent ledger called the blockchain, which is a running ledger of all the transactions that have occurred. In this process, many cryptocurrency transactions are bundled into a block. Figure II.1 gives a schematic picture of the process by which additional blocks are added to the blockchain. ‘Miners’ assemble a group of transactions into a block, and then attempt to solve a computationally intensive puzzle. When they are successful, their block is loaded onto the end of the blockchain. A ‘proof of work,’ evidence that the miners have successfully solved the puzzle, is included with the block, to show everyone that the puzzle was solved. As we will see, it is this ‘proof of work’ process that makes Bitcoin unsustainable.

Here, we will concentrate almost exclusively on Bitcoin. Although there are currently more than 2,500 different cryptocurrencies, as of July 2024 the market capitalization of Bitcoin was over 50% of the total value of cryptocurrency. Thus, Bitcoin continues to dominate the field of cryptocurrency. Because there are no individuals who check the verification of data blocks, one has to rely on automated systems to perform this verification task. Bitcoin has adopted a system called proof of work. This concept was introduced by Hal Finney in 2004. Our claim that the Bitcoin system is unsustainable is based on the proof of work system that Bitcoin uses to allow users to add an additional block to the blockchain.

Proof of Work:

In the ‘proof of work’ system, all would-be Bitcoin ‘miners’ participate in a network where each Bitcoin transaction is submitted for validation by all miners. Each miner has the opportunity to assemble a number of authenticated transactions into a block. But the miners compete against one another for the opportunity and reward that comes with adding a new block to the blockchain of all previously approved transactions. Each transaction and each block in the blockchain is identified by a unique 256-bit binary number (or equivalently, 64-digit hexadecimal number) called a cryptographic hash. The miner’s task is to generate a hash header for the new block by combining the hash header of the last block in the blockchain with the identifiers for all transactions in the new block and adding to all this a random integer called a “nonce.”

The miner then sends this combined information through a program called a hashing algorithm that generates a new hash unique to the provided input, which is akin to a lottery ticket. The hash output cannot be predicted from the input to the hashing algorithm, and a change of even a single character or a unit change to the nonce in the input will lead to an entirely different output hash. If the hash is smaller than a pre-assigned difficulty target, then the miner gets to add their block to the blockchain, and they are given a reward. In the far more likely event that the lottery ticket hash is not small enough, the miner’s program chooses different random nonces to add to the transaction information and iterates the process many (typically, trillions of) times per second. There is no shortcut alternative to random iterations to try to generate a small enough hash.

The blockchain system is arranged to determine the rate at which blocks are added to the blockchain. Let’s say that the system is designed so that one block will be added to the blockchain every ten minutes (this is the rate at which new blocks are currently being added to the Bitcoin blockchain). The difficulty target takes into account the number of data miners in the network and the rate at which they are completing the hashing algorithm; the target determines how many attempts per second must be submitted before a solution is obtained.

The successful data miner adds their block to the blockchain. That block contains the winning hash number, so everyone can see that the miner won the blockchain lottery. The new block also contains the hash number for the previous block in the chain. The sequence of hash numbers creates a ‘chain of proof’ that all blocks are valid. To give a real example, on May 17, 2024, block 843,900 had a difficulty target of 83.148T, or 83.148 trillion attempts per second per miner (one trillion = 1012), in order that one miner would be likely to meet the difficulty target within 10 minutes. And the winning hash for that block was the hexadecimal number: 000000000000000000033028b3c8296ed776653032030cd01290f4345f5a9b6e. Note the 19 zeros, corresponding to 76 binary zero bits, at the beginning of that hash. The fraction of all 256-bit binary numbers that begin with 76 or more zeros is 1.3 x 10-23, meaning that it may take on the order of 100 billion trillion random tries – or about 2 million mining computers each carrying out 83 trillion hashing calculations per second — to generate one hash that small in 10 minutes!

So, why is the difficulty target so hard to achieve? The data miner who adds a block to the blockchain receives a reward in Bitcoin. On July 18, 2024 the value of one Bitcoin was approximately $63,813. The enormous current value of Bitcoin means that the data miner is rewarded handsomely for successfully adding a block to the chain. For example, in November 2020 the reward for adding a block was 6.25 Bitcoins; given the value of Bitcoin at that time, the miner would be rewarded $111,875 for 10 minutes of computation. The system was designed at the start to eventually cap the total number of Bitcoins that would be put into circulation at 21 million. To meet that goal, the reward for adding a new block is designed to be reduced by successive factors of two from its initial (2009) value of 50 Bitcoins, in steps over time. As of July 2024, the reward for adding a block had been halved to 3.125 Bitcoin. In addition to the reward, the successful miner also receives transaction fees in Bitcoin paid by each of the parties involved in transactions they want added to the blockchain. So, even as the number of Bitcoins in circulation approaches saturation and the reward grows small, successful miners will still compete for the transaction fees.

As a result of the competition for a progressively scarcer resource, Bitcoin miners use enormously powerful banks of computers with specially designed computer chips, and programs that are optimized for speed in solving the hash algorithm. It should be clear that in the ‘proof of work’ system, obtaining faster computer chips or more efficient computer programs can provide great advantages for data miners. And these miners compete with other groups of miners spread across the globe. Data miners are generating extraordinarily large numbers of attempts to add a block to the chain; as a result, the difficulty target is then astronomically stringent, in order to achieve the goal of adding one new block every ten minutes to the Bitcoin blockchain. And as more and faster computers get added to the mining network, the difficulty gets progressively more challenging.

Bitcoin mining resource consumption:

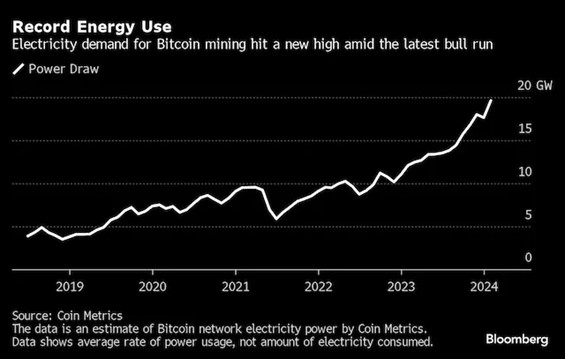

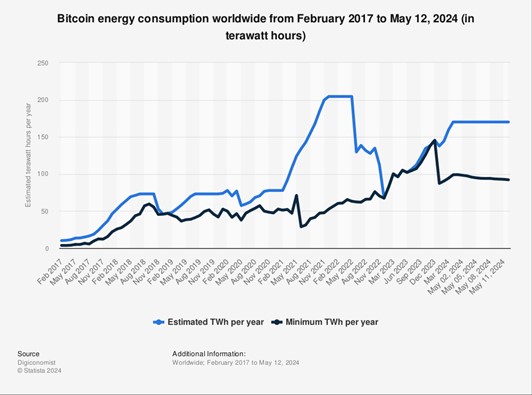

So, how much energy is currently being used in cryptocurrency data mining? Figure II.2 shows the average global use of electrical power in Bitcoin mining vs. time, in Gigawatts (a Gigawatt is one billion Watts or 109 Watts) over the past five years. One can see that the rate of power usage has increased by a factor of four in just five years, or a 62% increase year by year in power usage. Figure II.3 shows the banks of computers in one Bitcoin mining farm. Figure II.4 shows the worldwide Bitcoin energy consumption in the past five years, in Terawatt-hours (TWh, where 1 Terawatt is one trillion Watts, or 1012 Watts). The blue curve is the estimated global energy consumption, which rises from about 10 TWh in 2017 to 150 TWh in 2024. (The 2024 estimate is to be compared to the estimate of 200 TWh for all cryptocurrency mining indicated in Fig. I.2.) The graph includes both the estimated energy consumption per year, and also the minimum energy consumption; this is because at present, estimates of energy consumption in crypto mining have large uncertainties. The energy consumption increases rapidly each time the Bitcoin reward is halved and also whenever the Bitcoin value is surging.

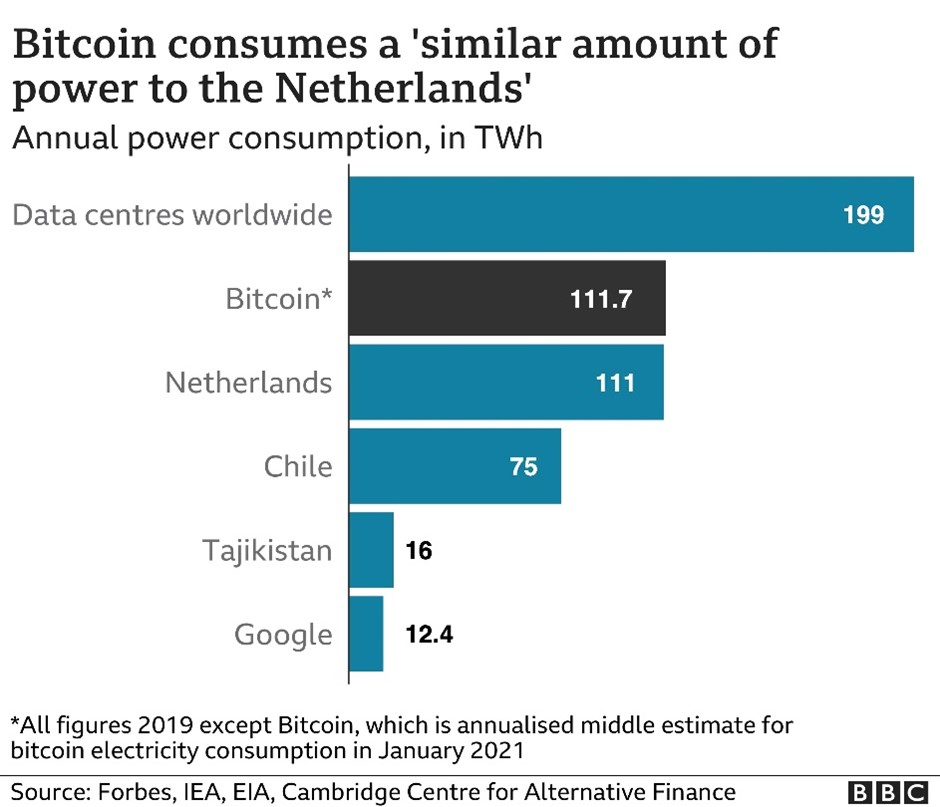

In order to gauge the magnitude of energy being used in cryptocurrency mining, Fig. II.5 shows the annual energy consumption in 2019 for all cryptocurrency data centers, which amounts to 199 Terawatt-hours. The figure for Bitcoin mining alone is about 112 TWh, or more than half the energy from all cryptocurrency transactions (the Bitcoin energy usage is the annualized consumption measured in Jan. 2021). For comparison are shown the energy usage for three countries, the Netherlands, Chile and Tajikistan. Bitcoin mining consumes the same energy as that of the Netherlands, while this mining uses significantly greater energy than Chile or Tajikistan. Finally, the energy used in Bitcoin mining in 2021 is more than 9 times the annual electrical energy consumed by all Google users worldwide.

In 2023, the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health issued a study of the effects of cryptocurrency mining. Their study estimated that the total energy consumed in cryptocurrency mining during the 2020-2021 year was 173.4 Terawatt-hours (this compares to the 200 TWh estimated in Fig. I.2 for 2022, reflecting the uncertainty in this figure). The UN study calculated that the carbon footprint from these operations was equivalent to burning 84 billion pounds of coal per year, or of operating 190 power plants fueled by natural gas. However, as pointed out in this study, energy consumption was only one of the impacts of crypto mining. The vast energy demands for crypto mining computers put great stress on power plants. Those plants require immense amounts of cold water to cool the hot water emitted from the plants. The additional amount of water needed for data mining would fill 660,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools; this is equivalent to the water needs of 300 million people in sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, the land footprint of cryptocurrency mining clusters was 1.4 times the size of Los Angeles. And without government regulation, all of these resource demands are likely to continue growing rapidly as new Bitcoins grow scarcer and increase in value.

As of 2021, Bitcoin mining operations relied heavily on fossil fuel sources. Figure II.6 shows the estimated mixture of energy sources that were used in Bitcoin mining in that year. Coal burning accounted for 45%, while natural gas accounted for 21%, hydro power for 16%, and nuclear for 9%. Other renewable resources such as solar, wind and bioenergy accounted for 8%. Given the mixture of energy sources shown in Fig. II.6, in the 2020-2021 year Bitcoin mining emitted over 85.9 megatonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere. If one attempted to mitigate this release of carbon dioxide by planting trees, it would take 1.9 billion trees; this would cover an area the size of Switzerland, or alternatively would take up an area equal to 7% of the Amazon rainforest. A study of the environmental impact of Bitcoin concluded that in the United States, “each 1 USD (US dollar) of Bitcoin that was created was responsible for 0.49 USD in health and climate damages.” Furthermore, another study argued that if cryptocurrency mining continues to increase, it could push global average temperature increases above 2o C over the pre-industrial average global temperature.

It should be noted that these figures have changed significantly in recent years. Until the middle of 2021, the country with the largest crypto mining industry was China. However, in June 2021 China closed down most of its crypto mining activities, as Chinese officials realized that the large expenditure of energy in cryptocurrency was interfering with their climate change target of becoming carbon-neutral by 2060. As a large fraction of China’s energy usage came from coal burning, the fraction of crypto energy expenditure from burning coal will decline, while in the past few years crypto mining has increasingly relied on renewable energy sources.

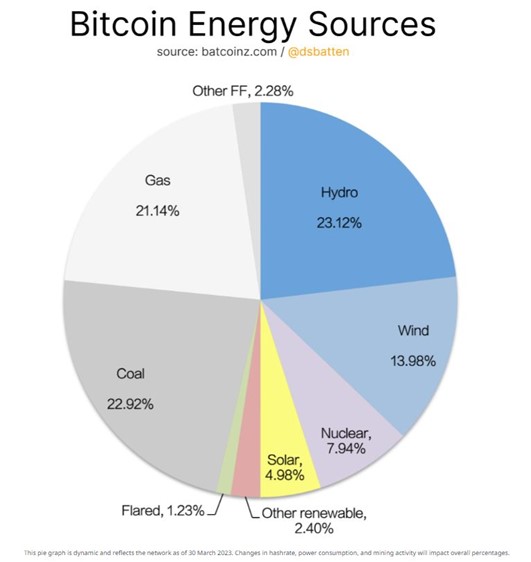

Figure II.7 shows the mix of energy sources used in Bitcoin crypto data mining in 2023. This is an estimate from batcoinz.com. As we noted, when China closed down most of their crypto mining operations in June 2021, this would decrease the amount of coal burning. It is claimed that much of the off-grid crypto mining is hydro-powered, and that this was not included in the estimate shown in Fig. II.6. When that off-grid computing is included, the claim is that the contribution from hydro power jumps to 23%. There are several “sustainable mining” companies that rely mainly or entirely on hydro power for their mining operations. The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance estimates the current Bitcoin data mining network annualized energy demand. If 100% of the data mining utilized hydro power as the energy source, the energy would be 91.78 Terawatt-hours; using their best guess as to the energy mix for data mining, they obtain 159.85 TWh; and if all of the crypto mining used coal burning, it would be 286.25 TWh. This highlights the significant uncertainties associated with crypto data mining energy use.

Figure II.7 also shows a significant increase in wind energy sources compared to Fig. II.6. It is claimed that a major source of wind energy comes from the Electricity Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) grid. However, a less optimistic view of the Texas electrical grid comes from an article by Keaton Peters in the July 2024 issue of Mother Jones. Peters points out that the Texas grid has experienced many outages and shutdowns. He notes that at present, crypto miners can draw 2,600 Megawatts of power from the grid, roughly the amount used by the city of Austin. However, ERCOT estimates that by 2027, as much as 43,600 Megawatts of additional energy demand may be added to the Texas grid, and that “currently, the crypto mining industry represents the largest share of large flexible loads seeking to interconnect to the ERCOT system.” To deal with this large demand, Texas is anticipating new natural gas power plants, rather than hydro or wind power.

Some advocates of crypto data mining claim that this data mining could utilize “surplus” power provided by wind farms. This suggests that crypto mining might use essentially “free” energy from renewable sources. However, when wind farms produce more energy than the grid can process, that energy is stored in banks of batteries. The stored energy can later be released when needed by the grid. Furthermore, it does not seem feasible for data mining operations to utilize energy only during limited periods of time. Crypto mining companies run their data clusters 24/7 in order to compete with other companies vying for the same block creation bonuses.

And even if 100% of crypto data mining used renewable sources of energy, these operations would still compete for energy with growing global human demands and would still generate enormous amounts of e-waste. Figure II.8 shows an e-waste recycling center in Hong Kong. Every 1.5 years on average, the computers used in data mining become obsolete and must be replaced. But these specialized computers cannot be used for other purposes, so they simply add to our enormous waste-disposal issues. In 2021, it was estimated that Bitcoin data mining generated 11.5 kilotons of e-waste every year. And as data mining increases along with the value of Bitcoin, the e-waste will also increase.

As of February 2024, the top countries in Bitcoin mining are the U.S. at 40%, China at 15% (despite having halted most of its crypto mining operations in 2021), and Russia at 12%. However, in the near future cryptocurrency mining is expected to increase rapidly in Africa and Latin America. The energy usage in Bitcoin mining is directly related to the price of Bitcoin. From 2021 to 2022, the price of one Bitcoin increased by 400%. This was accompanied by a 140% increase in the global Bitcoin mining network. Bitcoin miners are attracted to countries where energy is cheap and relatively unregulated. An interesting example is Kazakhstan. A few years ago, the price of energy in Kazakhstan was much lower than in the U.S. Furthermore, that country provided significant tax incentives to data miners. And many Kazakh power companies installed data mining operations onsite, as they could charge more for data mining operations than for supplying energy to the national grid. Thus, when China shut down its cryptocurrency mining operations, Kazakhstan rapidly became a major player in data mining.

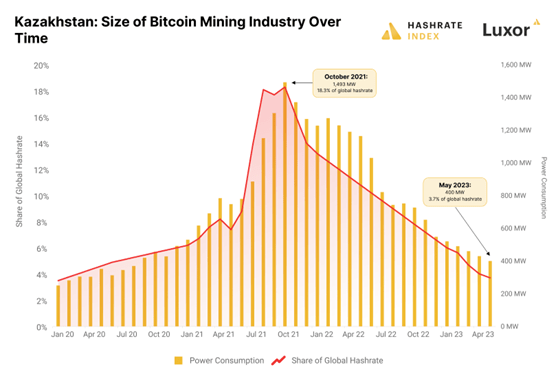

As a result, cryptocurrency miners flocked to that state, and in October 2021 the hashrate index (a measure of the amount of energy consumed in crypto mining) in Kazakhstan reached 18% of the world’s total; at that point the country was second in the world. However, Kazakhstan subsequently experienced a crisis as it was unable to handle the greatly increased demand for power. Eventually, the country began rationing energy. As a result, Bitcoin miners packed up and left that country, so that by May 2023 their share of the global hashrate had decreased to less than 4%. This is shown in Fig. II.9, which plots the cryptocurrency power consumption and global hashrate share in Kazakhstan from Jan. 2020 to May 2023. The solid curve (and left-hand axis) shows the percentage of the global hashrate in Kazakhstan, while the orange bars (and right-hand axis) plot the power consumption in MegaWatts. The two quantities are very closely, but not perfectly, correlated. It can be seen that the power consumption peaked in Oct. 2021, while by May 2023 it had dropped by nearly a factor of four from its peak.

The Kazakhstan experience illustrates another issue with cryptocurrency data mining. If energy sources are plentiful and energy use is largely unregulated, data miners can move in, erect warehouses filled with specialized computers, and begin using vast amounts of electric power. However, if data mining becomes unprofitable, or if cheaper alternatives present themselves, data miners can abandon their companies overnight. When Kazakhstan’s energy grid became overwhelmed with crypto mining, it rationed energy and tried to control the behavior of data miners by introducing regulations and taxing the miners. However, at present miners are free to abandon a country in search of areas with few regulations and cheap electric power. So, regulations and taxation by individual countries may have little influence on reducing the energy generated in crypto data mining.

The ’Proof of Stake’ Concept:

There is an alternative to the ‘proof of work’ concept, as a means of determining who can add a block to the blockchain. We have described the ‘proof of work’ concept used in the Bitcoin system and in several other cryptocurrencies. The ‘proof of stake’ concept was devised in order to avoid the extraordinarily large energy costs now required for a proof of work system. In the proof of stake system, a group wishing to add a block to the blockchain stakes a certain amount of their own cryptocurrency as collateral. They vouch for the validity of their block – in particular, they guarantee that the transactions in the block are legitimate, and that a given transaction in the block is not “double-spending” cryptocurrency spent in an earlier transaction.

In the proof of stake system, one of the groups wishing to load a new block is chosen randomly, and they load that block onto the blockchain. As a means of avoiding bad actors, the successful block creator is required to spend a small amount of crypto. The successful block creator then receives a reward for loading a new block onto the blockchain. Furthermore, if a creator is found to have violated the rules with their block or have behaved dishonestly, the network can punish violators by ‘burning’ some of their cryptocurrency; this is a process called ‘slashing’ and represents a penalty against bad behavior. It should be obvious that in the proof of stake system, there is no need to expend vast amounts of computer time; hence the environmental costs are massively decreased in the proof of stake system.

The most prominent example of proof of stake is the Ethereum cryptocurrency. Ethereum is currently the second-largest cryptocurrency, with a market cap just about 1/3 that of Bitcoin. In September 2022, alarmed by the exorbitant energy costs of the proof of work system, Ethereum switched to a proof of stake system. The current requirement for a stake in the Ethereum system is 32 Ether (as of July 22, 2024 one Ether token was worth roughly $3,462 USD). Each stake purchases one lottery ticket. One can purchase additional tickets for 32 Ether apiece. The more lottery tickets one holds, the greater their chance of winning the lottery and loading a block onto the Ethereum blockchain. Every twelve seconds a new block is chosen randomly from blocks submitted by stakers. As a result of this change, the energy costs associated with Ethereum dropped by 99.95% compared with their previous ‘proof of work’ method. As advertised, adopting this new system made Ethereum a sustainable product.

Why doesn’t Bitcoin change to the proof of stake concept? First of all, the largest data mining companies are giant corporations with a vested interest in maintaining their profits. So long as Bitcoin is largely unregulated, it can continue to use vast amounts of energy in data mining. A claim made by advocates of proof of work (PoW) is that the proof of stake (PoS) system has not yet demonstrated that it is robust against bad actors. Because the PoW blockchain requires enormous amounts of computer time to load a block, it is nearly impossible to alter earlier blocks in the chain for nefarious purposes, such as double-spending one’s Bitcoin; the computing time required to do this is daunting and every computer on the network contains a copy of the blockchain. However, since the PoS method requires so little computational time to create and load a block, this also makes it relatively easy to modify earlier blocks on the blockchain. However, after another year or two where Ethereum uses the proof of stake method, one should be able to assess the reliability of that system.

Advocates of the proof of work system argue that the proof of stake system may lead to consolidation among a small number of block creators. They claim that the proof of work system is ‘democratic,’ since anyone can start a data mining operation while the amount of crypto that is staked as collateral is often very large, and thus the proof of stake system can move towards one or a very small number of block creators dominating the system. We find this argument unconvincing. At present, only billionaires can compete in Bitcoin mining, since the costs of purchasing, programming and maintaining these computer farms are astronomical. Furthermore, even giant data mining companies now frequently join forces to run these vast computations. It remains to be seen whether the number of block creators tends to decrease in the proof of stake system.

Making Cryptocurrency More Sustainable:

Groups that sponsor cryptocurrencies are aware of the issues with enormous energy demand in the proof of work system. In 2021, a Crypto Climate Accord was created when over 150 crypto companies signed an accord that was inspired by the targets in the Paris Climate Agreement. They describe the Climate Accord as “a private-sector-led initiative for the entire crypto community focused on decarbonizing the cryptocurrency industry in record time.” The group now has over 250 signatories. They describe their goal as “achieving net-zero emissions from electricity consumption associated with all of their respective crypto-related operations by 2030.” They promise “To deliver the crypto industry an open-source toolbox of tech solutions to decarbonize and prove progress.”

We remain skeptical that these industries can achieve “net-zero emissions from electricity consumption” in just 6 years. We have seen a number of suggestions for lowering emissions or for mitigating their effects. One method is to use “carbon-offset pricing.” This method uses a voluntary fee paid by companies that emit large amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. Currently, companies that voluntarily provide these fees are paying about $6 – $8 a ton for sequestering carbon in forests; the price is generally less if a company purchases energy produced by wind or solar. However, a climate envoy from the Asian Development Bank described a study concluding that the price of carbon offsets needs to rise to a level of $25 – $35 per ton in order for polluting companies to mitigate the effects of their release of CO2. Furthermore, at the COP28 climate change meeting to be held in Dubai in November 2024, negotiators are expected to produce firmer rules on what constitutes ‘good’ carbon pricing. It remains to be seen whether crypto mining companies will increase their commitments to effective carbon-pricing offsets.

Another method for ‘green’ crypto mining involves capturing methane flares from underground wells and using the energy from those flares to power their data mining programs. Methane from the wells is burned to produce CO2, and the energy released in this process is used to operate banks of crypto mining computers. Since one ton of methane produces the same greenhouse-gas effect as 80 tons of CO2, methane burning reduces the overall amount of greenhouse gases that are released to the atmosphere. A 2022 report by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy concluded that “crypto-asset mining operations that capture vented methane to produce electricity can yield positive results for the climate, by converting the potent methane to CO2 during combustion… and …is more likely to help rather than hinder U.S. climate objectives.”

A company called Diversified Energy Company PLC has purchased a large number of natural gas wells in Pennsylvania. They installed machinery that captures methane being emitted in flares from these wells. The captured methane is burned to produce CO2 and release energy. Diversified Energy claims that their operations will decrease the amount of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere. However, an article in DeSmog.com questions these claims. It turns out that Diversified Energy purchased thousands of old, low-producing wells in Appalachia. These wells had been shut down because they were producing very little natural gas. When Diversified Energy re-started these wells to burn methane flares that powered data mining operations, they were producing additional CO2 emissions by opening up wells that had previously been shut down. Furthermore, Diversified Energy had installed the data mining operations without getting permission from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. A study by the Ohio River Valley Institute concluded that “taxpayers could be left with a massive bill for cleaning up the wells that Diversified leaves behind, as well as an ongoing discharge of climate-warming greenhouse gases.” So, using methane flares from natural gas wells for crypto data mining is a technique that needs to be investigated very carefully, before it is endorsed as a method for decreasing the release of greenhouse gases.

— Continued in Part II —