September 27, 2023

I: The Fukushima Reactor Disaster

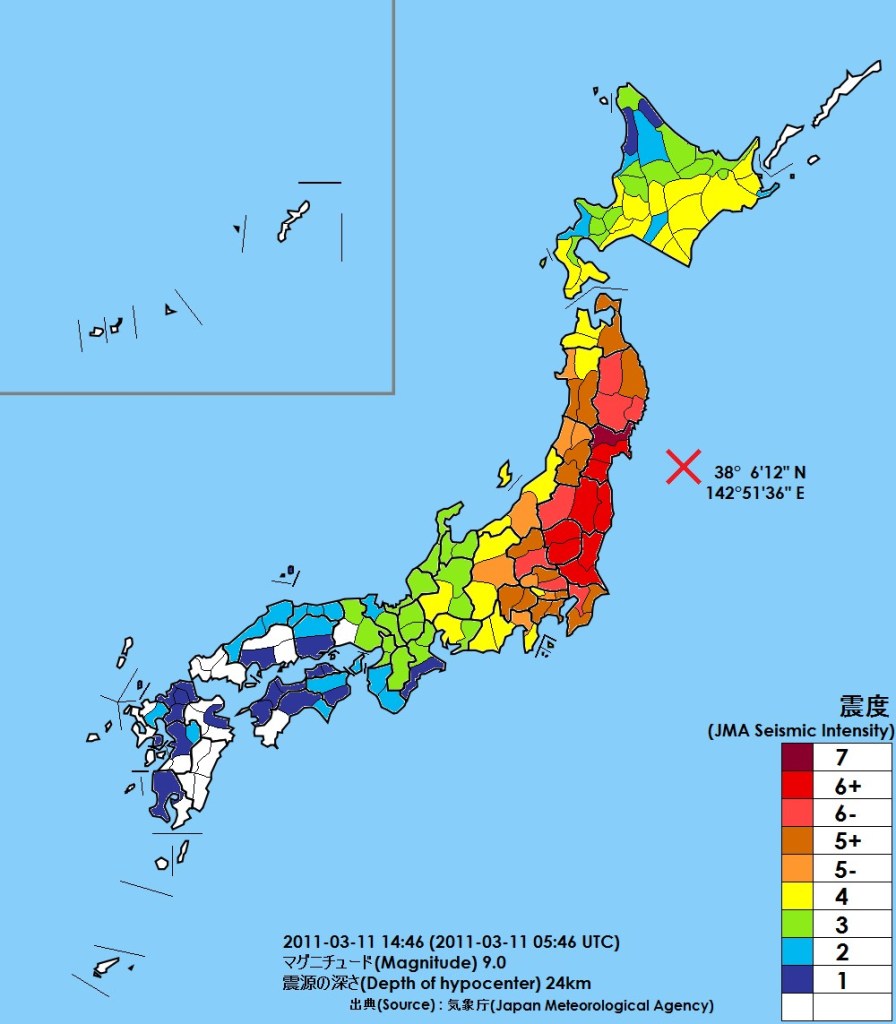

On March 11, 2011, the Tohoku earthquake occurred, centered under the ocean off the East coast of Honshu Island, with an epicenter marked by the red X in Figure I.1. The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor complex, on the east coast of Honshu, withstood the shaking generated by the massive earthquake that registered 9.2 on the Richter scale. We have previously discussed the earthquake and the massive tsunami created by the quake in an earlier post on our Debunking Denial Website. Here, we will briefly summarize the damage done to the nuclear power plant and the release of radioactive materials into the atmosphere and into the sea adjoining the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor complex. Then, we will discuss the accumulation of radioactively contaminated water at the Fukushima reactor complex, the process that has been developed to treat the contaminated water, and the release of treated water into the ocean. Much of our argument relies on an article by Prof. Attila Aszodi of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics.

Figure I.1: Epicenter of the March 11, 2011 Tohoku earthquake off the eastern coast of Honshu Island in Japan (red X). The tsunami generated by that quake precipitated the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi reactor complex.

In the hours following the earthquake, the Fukushima Daiichi plant was struck by two giant waves from tsunamis that resulted from the quake. At the Fukushima reactor complex, these waves reached a height of 14 – 15 meters; they completely overwhelmed the sea wall constructed adjacent to the Fukushima plant, which was 5.7 meters above sea level. The tsunami cut off the main power to the reactor, but it also knocked out the connection between the backup batteries and the reactor cores. This meant that no emergency cooling water was provided to the reactor cores. Without this cooling water, temperatures rose rapidly in the cores of three of the five reactors in the complex. Eventually the core temperatures reached a level where the cladding around the fuel rods melted; this led to chemical reactions that produced hydrogen gas held under very high pressure in the reactor vessels. The hydrogen reacted with oxygen and produced chemical explosions in three of the reactors.

The resulting explosion released radioactive materials from the reactor cores in two ways. First, large clouds of gas containing radioactive materials were released into the atmosphere surrounding the Fukushima complex; second, radioactive materials from the reactor cores were released into the sea surrounding the complex. Figure I.2 shows fire boats pouring seawater into the reactor complex in an attempt to extinguish the fires resulting from explosions in the reactor core, and to cool the extremely hot radioactive fuel rods. The explosions, combined with the radioactive contamination of water pumped into the reactor complex, resulted in the release of a significant amount of radioactive materials around the Fukushima plant. The two most dangerous radionuclides were Iodine-129 (with a half-life of 15.7 million years) and Cesium-137 (with a half-life of 30 years). Of these, roughly 80% of the release was into the ocean and into rivers adjoining the Fukushima complex. Over 300,000 tonnes of radioactive material were released immediately following the accident.

Figure I.2: Fire boats spraying seawater over the reactor core units at Fukushima Daiichi in an attempt to extinguish the fires in the reactor cores and cool the fuel rods in the cores.

In April 2011, Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), which administers the Fukushima site, discharged 11,500 tonnes of untreated radioactive water into the ocean. This was done to free up storage space for even more contaminated water. A second discharge of 300,000 tonnes occurred in May 2011. From 2011 to 2013, groundwater beneath the Fukushima site was contaminated with radioactive materials. However, for two years following the accident, the management at TEPCO denied that this leakage had occurred. The lack of candor from TEPCO has contributed greatly to the skepticism of Japanese citizens for official pronouncements regarding the safety of the reactor complex.

Since the reactor cores remain at very high temperatures due to nuclear reactions from the fuel rods, beginning in 2011 water has been pumped into the reactors to cool them. In addition, rainwater runs past the core elements and picks up radioactive materials from the core; and finally, groundwater passing through the reactor complex becomes contaminated with radioactive materials. The total amount of contaminated water is about 90 – 100 cubic meters per day. This water is collected in large tanks located within the Fukushima reactor complex, with each tank holding 1,300 m3 of contaminated water. Figure I.3 shows an aerial view of the Fukushima reactor complex. In the middle and bottom of the Google maps satellite image, one can see the tanks that hold the radioactively contaminated water. Figure I.4 is a photo of some of the 1,000 tanks on the Fukushima complex.

Figure I.3: A Google maps satellite image of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor complex. In the middle and lower parts of this complex one can see the large number of tanks that hold water that has become contaminated with radioactive nuclides after passing across the reactor cores.

Figure I.4: Some of the 1,000 tanks at the Fukushima reactor complex that hold contaminated water.

Altogether, the tanks can hold 1.37 million cubic meters of water. Because of the presence of long-lived radioactive nuclides in the water, it is unsafe to release it into either the air or surrounding water. It is also unsafe to simply store the water forever on the reactor site. The site is still subject to natural disasters such as typhoons, earthquakes or tsunamis, which could cause yet another disastrous release of radioactive materials into the region. As of a few months ago, the tanks held 1.33 million m3 of radioactive water; if no action is taken by early 2024, 100% of the tanks will be full of water. As a result, the TEPCO management has developed a plan to treat the water before discharging it. This is called the Advanced Liquid Processing System or ALPS, and is described in detail in the following section.

II: The Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS)

The Advanced Liquid Processing System or ALPS is a procedure involving several steps, which is designed to remove nearly 100% of the radioactive contamination from the water in the Fukushima complex holding tanks. In the first step, two of the most dangerous radionuclides, Cesium-137 and Strontium-90 (28.9 year half-life), are removed from the tanks by chemical reactions. These two substances are present in large quantities, and they are dangerous because when they decay they emit high-energy radiation that damages animal and plant cells. They also tend to accumulate over time in cells. The water in the holding tanks is then treated with precipitating agents that remove 60 additional radioactive isotopes from the contaminated water. The first stage is to subject the liquid to iron co-precipitation; this removes alpha-emitting nuclides and organic molecules. The second stage uses carbon co-precipitation which removes alkali earth nuclides. Following the two successive ALPS treatments, only two radioactive isotopes, tritium (an isotope of hydrogen with one proton and two neutrons in the nucleus, and a half-life of 12.3 years) and carbon-14 (with a half-life of 5700 years), remain in the water in any significant amount. Figure II.1 shows the official limits on the remaining concentrations of 64 radioisotopes after the ALPS treatment. The allowed activity concentration limits are expressed in units of Becquerel per Liter, and the half-life of the isotope in years is listed. For example, a concentration activity of 2,000 Becquerel per Liter means that each liter of water would experience 2,000 decays of that radioactive isotope per second. For all isotopes except tritium, the allowed limits are below what would be required for allowed concentrations in drinking water. In addition to the maximum allowed concentration of each radioactive isotope, there is a maximum allowed total concentration activity limit, in order that the treated water be acceptable for release back into the ocean.

Figure II.1: Maximum concentrations of 64 radioactive isotopes (62 that are removed in the ALPS process plus tritium and Carbon-14) allowed after treatment of radioactive water at the Fukushima reactor complex, in units Becquerel/Liter.

What About Tritium, and Why Can’t It Be Removed From the Contaminated Water?

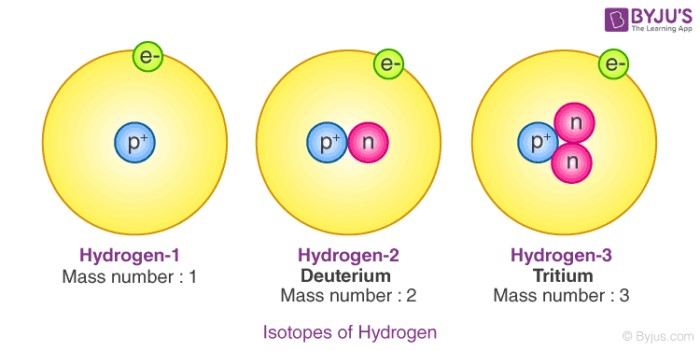

Tritium is an isotope of hydrogen. While normal hydrogen has only a single proton in its atomic nucleus, tritium has one proton and two neutrons, as shown in Figure II.2. Since every isotope of hydrogen has one proton and one electron in a neutral atom, all three isotopes of hydrogen are identical in their chemical reactions. Therefore, no chemical reactions will separate tritium from normal hydrogen.

Figure II.2: The three isotopes of hydrogen. Normal hydrogen or protium has just a single proton in its nucleus, while Deuterium has 1 proton plus a neutron, and the nucleus of Tritium has a proton and 2 neutrons. As each of these atomic isotopes has one proton and one electron, all three isotopes take part in chemical reactions in exactly the same way.

Separation of tritium from normal hydrogen is an exceptionally complicated and costly process, and would be completely unfeasible for the massive amounts of water at Fukushima. Fortunately, tritium is one of the radioactive isotopes that is least harmful to animals and plants. The half-life of Tritium is 12.3 years, meaning that every 12.3 years half of the atoms of a sample containing tritium will decay. Tritium decays by converting to Helium-3 (a nucleus containing 2 protons plus a neutron), while emitting an electron and an antineutrino. The antineutrino does not interact with anything. The electron is very slow-moving; released into the atmosphere, it will only travel about 5 mm in air; it will not penetrate a sheet of paper, nor will it penetrate the skin. The slow-moving electron will do very little damage to tissues or DNA if a tritium atom in the body decays. Furthermore, tritium does not accumulate in an animal or plant. The tritium generally is absorbed in water, and in the human body lasts only for a week or two before it is excreted in the urine. In many countries the permissible upper limit of tritium activity in drinking water is 1,500 Becquerel/Liter. By comparison, the World Health Organization’s limit for the tritium activity in drinkable water is 10,000 Becquerel/Liter. Tritium is produced by the interaction of cosmic rays with hydrogen in the atmosphere. Much of the tritium in the atmosphere today has resulted from atmospheric nuclear bomb tests which were carried out frequently in the 1950s to 1970s, and more than 95% of the tritium from bomb tests has already decayed. But tritium is also produced in nuclear reactors and in plants that re-process reactor fuel rods.

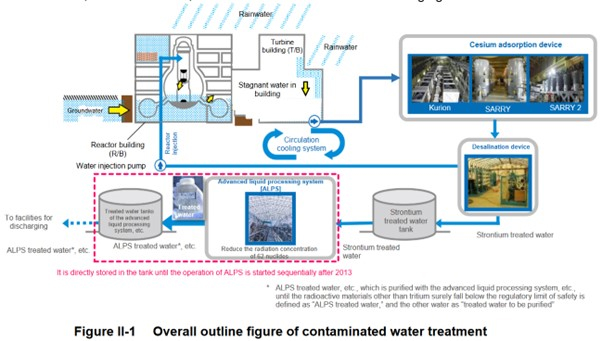

Figure II.3 is a schematic diagram of the treatment process for the radioactive water at Fukushima. Contaminated seawater, rainwater and groundwater is gathered into the storage tanks where it undergoes several processing steps. First, the Cesium-137 is removed in an adsorption process; the water is then run through a desalinization process that removes Strontium-90. After that the water is treated by the ALPS process. Finally, the treated water is mixed with seawater; this dilutes the Tritium content in the discharged liquid to bring the Tritium activity below 1,500 Bq per liter. This is identical to the limit on tritium activity of drinking water in most countries.

Figure II.3: A schematic picture of steps taken to treat water contaminated with radioactive isotopes. First, the contaminated water is run through a process that removes Cesium-137; next, Strontium-90 is removed from the liquid; next, the water is sent through the ALPS system. After this, the treated water is mixed with normal seawater to further dilute the relative amount of tritium; then it is sent for discharge into the ocean.

The TEPCO ALPS plan has been approved by the Japanese nuclear safety agency NRA and the International Atomic Energy Agency IAEA. The water release plan also contains many measurements and tests to ensure that the levels of tritium in the released water are sufficiently low. The goal is to ensure that those Japanese who receive the highest doses of tritium from the released water have an annual exposure of less than 50 µSv (micro-Sieverts). This is 5% of the annual dose limit for Japanese citizens. The plan is to release all of the 1.33 million cubic meters of contaminated water over a 30-year period. The TEPCO plan also calls for extensive testing of marine life off the Japanese coast. The IAEA has certified that the monitoring and investigation programs would be adequate to protect human and marine life in Japan.

III: International Reactions to the TEPCO Plans for Treatment and Testing of Released Water

The ALPS treatment plan developed and carried out by TEPCO, and the release of previously contaminated water into the sea surrounding the Fukushima reactor complex has provoked strong statements, both in favor of and against, this proposal. We will briefly review those agencies and countries that have certified the proposal as reasonable. Then we will discuss those groups that have come out against the proposal.

First, the International Atomic Energy Agency states that “Most nuclear power plants around the world routinely and safely release treated water, containing low level concentrations of tritium and other radionuclides to the environment as part of normal operations … The regular practice in nuclear installations is the authorized and controlled discharge of tritiated water into nearby water bodies, such as rivers, lakes or coastal areas. Water discharges at nuclear power plants are authorized releases and are closely monitored by the operators and regulators to ensure safety.”

The TEPCO administration presented their ALPS processing system to the IAEA, and that agency reviewed it and agreed that the proposal and the measurement and testing protocols were consistent with the state of the art. TEPCO also presented their proposals to the Japanese nuclear agency NRA and to the Japanese government under Prime Minister Suga. Suga’s Cabinet unanimously approved the TEPCO proposal. On August 24, 2023, Japan began dumping the treated and diluted water into the Pacific Ocean, about 1 km from shore. Measurements of the sea water in that vicinity found that tritium levels were below the limits of detection (10 Bq/L). The Japanese Fishery Agency tested fish caught 4 km from the discharge site and found no detectable levels of tritium. In January 2020, an expert Japanese committee calculated that if all the contaminated water was discharged at once, it would provide residents of the Fukushima prefecture with a radiation dose of 0.81 micro-Sieverts per year; this should be compared with the dose from naturally occurring radiation of 2,100 micro-Sieverts per year. The Fukushima water would release far less than the overall tritium emissions limit of 22 trillion Becquerels (22 TBq) per year imposed by the International Atomic Energy Agency on the Fukushima plants during their normal operations. This compares with a release of 11,400 TBq by the French La Hague nuclear reprocessing site in 2018.

Government officials from countries such as the United States, France, Australia, the United Kingdom, Italy and Malaysia commended the TEPCO procedures for treating, releasing and monitoring treated water into the sea.

However, a number of governments, including several in South Asia, have objected strongly to the Japanese release of water from Fukushima into the sea. There was a large South Korean protest against the TEPCO action. The South Korean government issued a strong statement opposing this release. This was also reflected in polls showing that 80% of South Koreans opposed the water release plan, and 60% of those claimed they would no longer purchase Japanese seafood products. However, we can assert that the Korean protests are essentially completely political. First, South Korean nuclear plants release tritium into the ocean; radiation levels from Korean plants are almost ten times larger than the release at Fukushima.

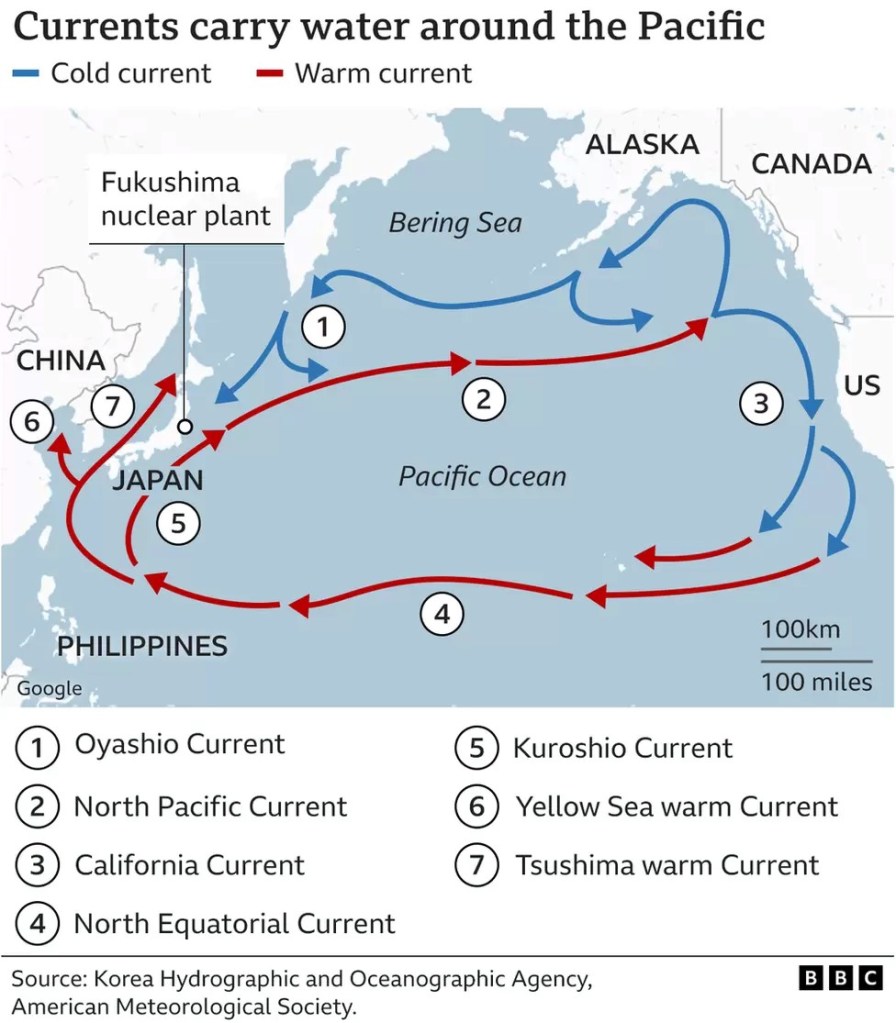

In addition, there have been protests from women who dive for seafood off the coast of Korea. They claim that the Japanese release of tritium makes the waters off Korea unsafe for them. We have already stated that Korean nuclear plants release water that has ten times the activity from radiation as from Fukushima. But water from Fukushima would have to travel at least 1,500 kilometers to reach traditional Korean divers. By that time the water would be diluted to an unbelievable degree and would contain no measurable level of tritium. Figure III.1 shows the major Pacific currents that could carry water from Fukushima to other countries bordering Japan. Water from Fukushima to South Korea and China would travel by the Yellow Sea Current and the Tsushima Current.

The Chinese government has also sharply criticized the Japanese for releasing the treated water at Fukushima back into the ocean. Once again, the Chinese protests are purely political. Like South Korea, water around Chinese nuclear reactors contains much higher levels of tritium than the water being released at Fukushima. The Chinese government seems to be using the water release as an excuse for demonizing the Japanese people and their government.

Figure III.1: Diagram showing major currents that carry water through the Pacific. Water originating at Fukushima would be carried to Korea and China via the Yellow Sea Current and the Tsushima Current.

In addition to official government responses to the situation at Fukushima, there have also been protests from “Green” groups in many countries. In Japan, a survey showed that 55% of respondents opposed the TEPCO plan; and 86% of those polled felt that this action would harm Japan’s reputation abroad. Figure III.2 shows people engaged in a Japanese protest against release of the Fukushima water. They are holding plastic fish with stickers indicating that the fish are radioactive. The protests are fueled in part by the hostility of the public to the TEPCO administration of the Fukushima reactors. TEPCO has a long history of withholding information from the public or making public statements that proved to be false. The track history of TEPCO provides a lesson in how lack of candor can produce great skepticism among the public.

Figure III.2: A Japanese protest against the release of treated water from the Fukushima reactor complex into the ocean. The protesters are holding plastic fish with stickers suggesting that the fish are dangerously radioactive.

There have also been protests by environmental activists against the release of the treated Fukushima water into the sea. Some of the protests explicitly target the release of water containing trace amounts of tritium. In this case, the protesters should be focusing their attention on nuclear reactors that release water with much higher tritium content than the treated Fukushima water. In other cases, environmentalists complain that the Fukushima water contains trace amounts of over 60 radionuclides. The environmentalists point to the history of chemicals such as DDT, which was touted as being perfectly safe before it was discovered that DDT accumulated in animals and plants and had significant negative long-term effects. They state that if low-level radioactivity is found to be harmful in the future, we will have released toxic substances into the oceans. We have noted that the radioactivity from the Fukushima treated water is very low compared to standards for drinking water, and at present everything we know about the biological effects of low levels of radioactivity suggests that it should be quite safe. At the moment, the preponderance of evidence suggests that the treated Fukushima water should not produce any harmful effects.

IV: Summary

In this short post, we have reviewed the March 2011 disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor plant, due to the massive tsunami caused by the gigantic Tohoku earthquake off the eastern coast of Honshu Island in Japan. That tsunami knocked out both the main electric power and the backup power; this resulted in an increase in the temperature in the reactor cores which led to chemical explosions in three of the Fukushima reactors. These explosions produced large amounts of radioactive material, some of which were released in gas clouds emitted from the Fukushima complex and most of which was released into the ocean and the rivers adjoining the Fukushima reactor.

In the two years following the reactor explosions, the Fukushima administrative agency Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) built one thousand tanks to hold water that had become contaminated with radioactive nuclides. Over time, those tanks gradually filled up with this contaminated water. If nothing was done with this water, all 1,000 holding tanks would become full in 2024. So TEPCO developed a plan to treat the water prior to releasing the treated water into the ocean. That plan involved several steps to treat the water, as shown schematically in Figure II.3. After treatment, the water would contain trace amounts of many radionuclides, but still large amounts of tritium. The TEPCO plan was to dilute the treated water with seawater, until the level of tritium activity was identical to the level of tritium in the water during normal operation of the Fukushima plant.

After treating the water with their Advanced Liquid Processing System or ALPS, TEPCO proposed releasing the water into the sea over a 30-year period. The first release of this treated water occurred in August 2023. That release was protested by several governments, and also by environmentalist groups. The protests by governments, particularly South Korea and China, were totally political, as the water released by the Japanese has considerably less radioactive activity than water released by nuclear reactors in both Korea and China. Environmental groups have criticized the Japanese actions on two points. The first is that the treated Fukushima water still contains tritium. However, the level of tritium is substantially smaller than that found in water surrounding working nuclear reactors or nuclear re-processing plants in many countries. The second point of criticism is that the water contains trace amounts of many other radionuclides (see the full list in Figure II.1). However, the levels of radiation in the treated water are exceptionally low, and radioactivity in the released water is significantly below the level required for drinking water.

Based on our current knowledge of the effects of radiation, the water released into the sea at the Fukushima reactor complex should be safe to drink or for marine life. The only danger would be that in the future one might discover that even minuscule amounts of some radioactive substances are harmful to plant or animal life. Given our current understanding of the biological effects of low-level radiation, this would be a very surprising development. For the time being, it appears that the TEPCO plan to remove radioactive materials from the contaminated water at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear complex has been a success.

Source Material:

Attila Aszodi, How the Plan for Releasing Treated Water in Fukushima Works, European Nuclear Society, https://www.euronuclear.org/blog/how-the-plan-for-releasing-treated-water-in-fukushima-works/

International Atomic Energy Agency, Fukushima Daiichi ALPS Treated Water Discharge – FAQs https://www.iaea.org/topics/response/fukushima-daiichi-nuclear-accident/fukushima-daiichi-alps-treated-water-discharge/faq

Wikipedia, Discharge of radioactive water of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discharge_of_radioactive_water_of_the_Fukushima_Daiichi_Nuclear_Power_Plant

BBC News, The Science Behind the Fukushima Waste Water Release https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-66610977

Mike Ives, John Yoon, Hisako Ueno and Olivia Wang, Seafood is Safe After Fukushima Water Dump, but Some Won’t Eat It, New York Times, Aug. 25, 2023 https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/25/world/asia/fukushima-water-seafood-japan-china.html