January 28, 2026

I. introduction

In our previous post Live Free AND Die, we have presented a large amount of data to demonstrate that mortality rates among voters in Republican counties – especially white, rural voters in the South and Appalachia – have been growing systematically worse throughout this century than mortality rates among voters in Democratic counties in the U.S. Many factors contribute to this mortality gap, including lifestyle, trust in science and medicine, and access to quality healthcare. But an additional important factor is politics. Republican politicians have traditionally not placed Americans’ health as a high priority for law-making at either the state or federal levels. They have tended to view healthcare as a privilege, rather than a right of citizens. They have viewed Medicare, Medicaid, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA, often called Obamacare) as exercises in socialized medicine that should be undermined. For fifteen years since the passage of the ACA, Republican politicians have claimed to be working on their own alternative non-governmental approaches to improving healthcare costs for Americans, without ever producing a viable plan. Now, under the second Trump administration, they have resorted to draconian funding cuts for both Medicaid and ACA tax credits, in the apparent hope that these programs will simply implode on their own as fewer Americans can take advantage of them.

Some measure of Republican attitudes toward healthcare is provided by the comments of various Senators and the Vice President surrounding the passage of Trump’s self-labeled “One Big, Beautiful Bill Act” in 2025. When the bill was under debate, Senator Joni Ernst of Iowa dismissed her constituent’s concern at a Town Meeting that the Medicaid cuts in the bill would cause many premature deaths. “We all are going to die,” was her dismissive response. Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky reportedly said in a Republican caucus meeting about the bill, “I know a lot of us are hearing from people back home about Medicaid, but they’ll get over it.” And perhaps the most tone-deaf comment (see Fig. I.1) came from Vice President JD Vance after the bill passed: “Everything else [in the bill] – the CBO score, the proper baseline, the minutiae of the Medicaid policy – is immaterial compared to the ICE money and immigration enforcement provisions.” Vance thus reduced trillion dollar cuts to Medicaid that would result in nearly 8 million Americans losing health insurance coverage to “immaterial minutiae,” giving voice to what Republicans think about the government providing health insurance.

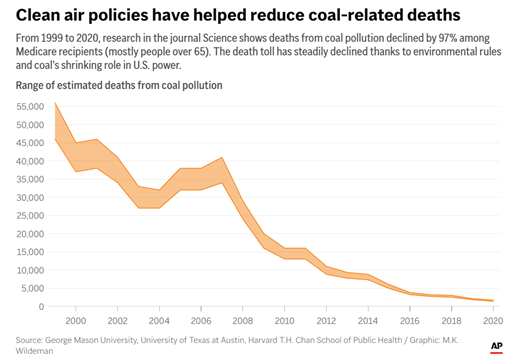

But it is not only Republican attitudes toward government health insurance that affect their constituents’ health. Republicans also tend to oppose all government regulation of industry. Although the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was launched in 1970 under Republican President Richard Nixon, Republican administrations ever since have been working to undermine its actual protections when affected industries complain about compliance costs. Under the Trump administration, current EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin appears focused on making America great again for polluters. He has proposed: exempting many coal power plants from meeting regulations on heavy metal (e.g., mercury) and toxic emissions into the atmosphere; abandoning standards for soot and fine particulate matter pollution; limiting wetlands protections and gas mileage limits; and decimating rules limiting emissions of greenhouse gases. Each of these changes threatens Americans’ health. In a recent opinion piece in the New York Times, Thomas Edsall labeled Zeldin’s plans as “a killing spree cloaked as deregulation.” As one example, we show in Fig. I.2 the rapid reduction in American deaths from coal plant pollution that has resulted from regulations Zeldin now proposes to roll back, at the same time that Trump has stated a goal to increase coal plants by ignoring their contribution to ongoing climate change.

Republicans’ distaste for government-funded health insurance and environmental regulations would already constitute a serious threat to the health of Americans. But Trump and his rubber-stamp MAGA (“Make America Great Again”) Senate have made matters much worse by nominating and confirming Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. as the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), thereby giving a home to the anti-vaxx movement in the federal government. In less than a year, Kennedy’s “Make America Health Again” (MAHA) program has transformed HHS and the Centers for Disease Control into a fount of misinformation about vaccines, autism, and other diseases. His hand-selected advisors on vaccine policy have supported changes to vaccine recommendations that will almost certainly boost diseases and deaths rather than Americans’ health. And he has instituted draconian cuts to staffing at the National Institutes of Health and to funding for critical medical research. All of these changes will jeopardize Americans’ health and serve to accelerate the mortality gap between Republican and Democratic voters. Indeed, as Thomas Edsall has recently opined in the New York Times, “The MAHA Pipe Dream is Going to Hurt MAGA the Most.” In our view, the combination of MAGA and MAHA should be known as MADA: Make Americans Die Again.

In this post we will attempt to quantify the likely health impacts of the most deleterious policies being adopted under the current Trump administration. We will deal with the Congressional cuts to health insurance in Section II, with cuts to medical and scientific research in Section III, with proposed regulatory changes in Section IV, and with the broad array of RFK, Jr.’s HHS policies in Section V.

II. legislative actions

The 2025 Budget Reconciliation Act – otherwise referred to as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act – aims to reduce spending on Medicaid by $1.035 trillion over ten years. It does this by restricting eligibility for coverage by a combination of new work and reporting requirements, together with abandoning efforts to streamline eligibility for both Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). It is estimated that the cuts will increase the number of low-income Americans without health insurance by roughly 8 million by 2034.

In order to estimate the geographic disparities in the impacts of these cuts, it is useful to first understand some basic features of Medicaid. It was signed into law in 1965 along with Medicare and was designed to provide health coverage to low-income people, pregnant women, some seniors, and those with disabilities. CHIP was added in 1997 to provide healthcare coverage to children in families whose incomes were too high to qualify for Medicaid but still too low to afford private coverage. The federal government establishes some basic features of Medicaid coverage but then allows individual states to determine details within those guidelines, including eligibility rules and which services are covered. Medicaid reimburses hospitals, doctors and other providers for care delivered to eligible patients using a combination of federal and state funds.

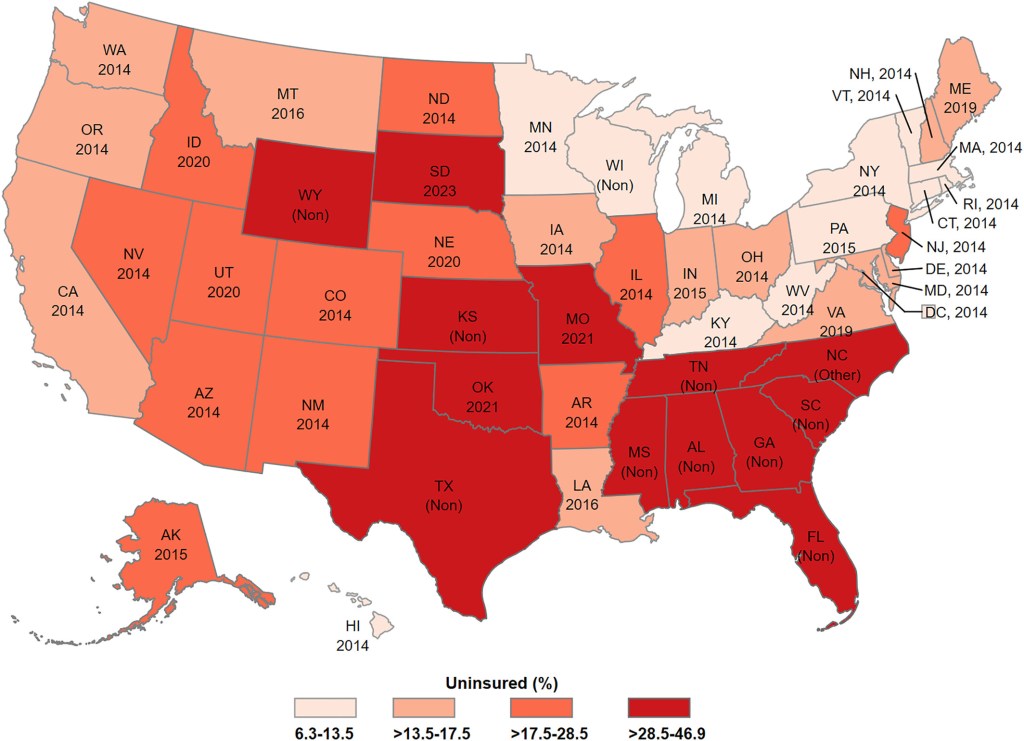

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed in 2010 during the first Obama administration provided authority for states to expand Medicaid coverage to individuals under age 65 in families whose income falls below 133% of the Federal Poverty Level. The federal government would fully fund coverage for the newly covered individuals for three years beginning in 2014, then reducing to 90% of the coverage by 2020. Initially, many states with Republican governors and Republican-dominated state legislatures refused to adopt the expansion. Some of those states have since chosen (often under citizen pressure) to adopt the expansion. With the ACA-authorized expansion there are currently about one-quarter of Americans, or more than 80 million people, whose healthcare is covered by Medicaid. An additional 10 million or more children are currently covered by the CHIP program.

The current situation is illustrated in the map in Fig. II.1, where it is indicated for each state whether it has expanded Medicaid coverage and, if so, the year of the adoption (2014 was the first year the expansion was authorized). The color coding of the states in Fig. II.1 indicates the percentage of the state’s inhabitants below the federal poverty level who have no health insurance coverage. It is clear that the highest percentages of uninsured fall among those Republican-led states that have adopted Medicaid expansion only since 2020 or not at all. (Although Wisconsin has not formally expanded Medicaid, it has its own Badger Care Plus program for low-income inhabitants and is thus among the states with the lowest percentage of uninsured.)

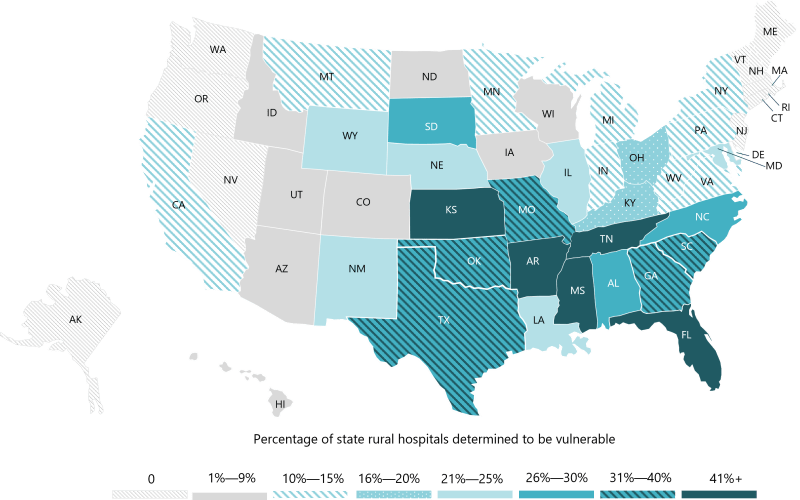

When individuals with no health insurance, including Medicaid, coverage get ill or injured, they generally avoid going to visit doctors or hospitals and their health suffers. In case of medical emergencies, hospitals are required by law to treat even the uninsured, but the costs are then generally absorbed by the hospital. Hospitals in rural areas that include many uninsured patients thus have a difficult challenge to remain financially viable. According to a 2025 Chartis report, “In the last 15 years, 182 rural hospitals have either closed or converted to an operating model that does not provide inpatient care (e.g., long-term care, Rural Emergency Hospital). This represents approximately 10% of the nation’s rural hospitals.” Among remaining rural hospitals, the Chartis report furthermore notes that “In [Medicaid] expansion states, the median rural hospital operating margin is 1.5%, and 43% are in the red. In our analysis, non-expansion states account for nearly 30% of all rural hospitals. 53% are in the red, and the median operating margin is -1.5%.” The Chartis report identifies 432 rural hospitals that are now vulnerable to closure, with the percentage in each state indicated in Figure II.2. Note again that it is almost exclusively states that house a majority of Republican voters which are most at risk. Florida, Tennessee, Kansas, Mississippi, and Arkansas lead the way with 40-50% of their rural hospitals at risk of closure. Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Georgia and South Carolina are not far behind with 31 – 40% of their rural hospitals at risk.

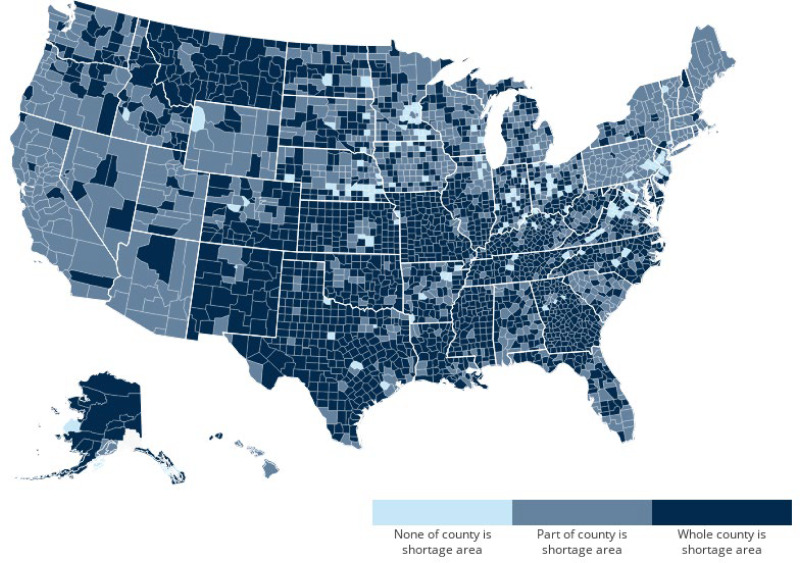

The past closures of rural hospitals in red states have contributed substantially to the growing partisan mortality gap in the U.S. Although the states that have not adopted the Medicaid expansion will see smaller than average Medicaid cuts from the 2025 Budget Reconciliation Act, it is still the red states with the most vulnerable rural hospitals that will be most seriously affected further by the cuts. The hospital closures will amplify the impact of the Medicaid cuts; in addition to the 8 million or so Americans likely to lose Medicaid coverage, a roughly equal number of Americans may retain coverage but lose easy access to hospitals for medical emergencies. Another indirect impact is that physicians tend to move away from counties that do not house viable hospitals. Figure II.3 indicates that much of rural America, especially in the South and Midwest, is already considered shortage areas for primary care health professional coverage. According to the Chartis 2025 report, “Access to primary care providers in rural communities is scarcest in Mississippi and Florida (both at the 13th percentile), Oklahoma (16th percentile), and Tennessee (17th percentile).” That situation will deteriorate further in the light of the enacted Medicaid cuts and will further impact the health of Americans.

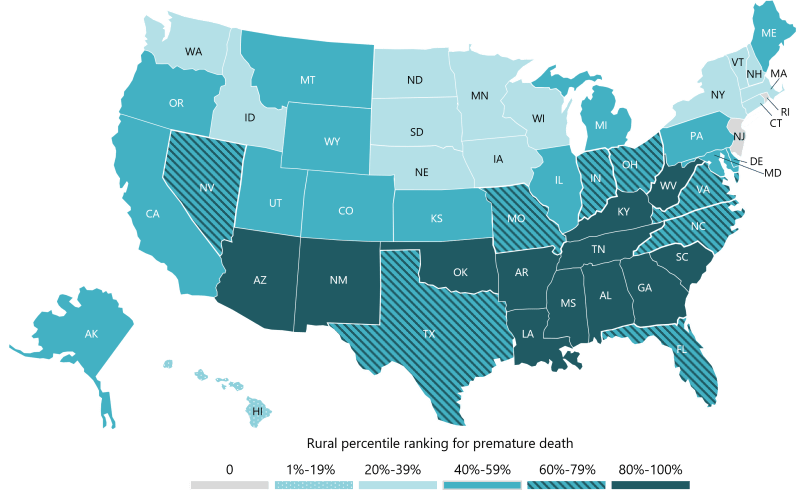

The lack of access to primary care providers and hospitals is one of the leading causes of premature deaths in the U.S. Chartis uses a premature death metric that accounts for the potential years of life lost before the age of 75, which is substantially worse in rural than in urban counties. Figure II.4 indicates the percentile ranking of the various states with respect to the rural premature death metric. The worst states, colored in the darkest color, mostly fall in the deep South and Appalachia. The premature death metric for these states will grow considerably in light of the enacted Medicaid cuts. We will return to estimate the additional number of preventable deaths likely to be caused by the healthcare changes in the 2025 act after first discussing other impacts of the act.

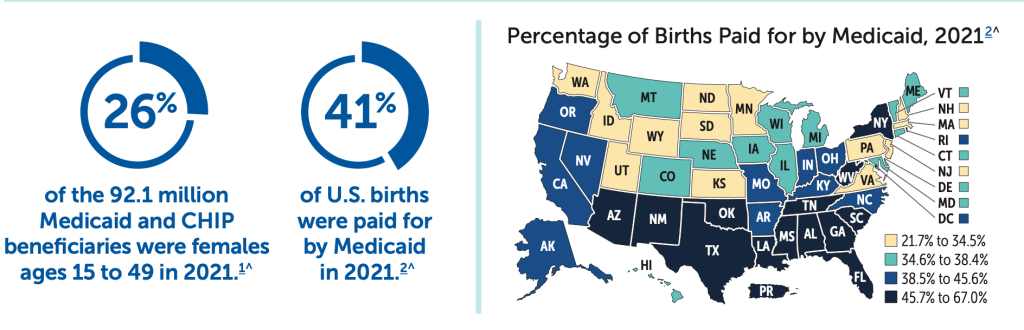

Medicaid covers a surprisingly large fraction of births in the U.S. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), of the 92.1 million Medicaid and CHIP beneficiaries in 2021, 26% were females of child-bearing age (15 to 49). And 41% of hospital births were paid by Medicaid. That percentage varied substantially among states, as shown in Fig. II.5. Louisiana, which already has a maternal death rate above those in Mexico and Nicaragua, had 70% of its rural births funded by Medicaid in 2021. Many of the states with the highest percentage of Medicaid-funded births already have maternal mortality rates above the U.S. average, and the U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rate among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries; in 2024, the U.S. maternal mortality rate was 17.9-19 deaths per 100,000 live births. Furthermore, a number of these states have adopted draconian anti-abortion laws in the wake of the Supreme Court 2022 Dobbs decision that overturned a federal right to abortion; those states have seen substantial increases in their maternal (and infant) mortality rates. For example, the maternal death rate in Texas increased by 56% from 2019 to 2022 in the wake of its anti-abortion law.

The anti-abortion laws in a number of red states have driven many maternal care providers away, so that they now have among the lowest numbers (less than 56) in the U.S. for maternity care providers per 100,000 women of ages 15-49. Furthermore, nearly 300 rural hospitals under financial stress have stopped offering obstetric care over the past 15 years. The enacted Medicaid cuts are going to exacerbate these trends and thereby increase maternal and infant mortality rates, especially in rural areas of the South, and are going to decrease fertility rates in the U.S. The Medicaid cuts are from this viewpoint a peculiar policy for a Republican Party that aims to increase Americans’ fertility.

It is not only the Medicaid cuts that jeopardize Americans’ health. Aside from those covered by Medicaid expansions authorized under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), about 24 million Americans currently have healthcare coverage through insurance plans purchased on the ACA marketplace. That number has nearly doubled since 2021, when Congress enacted expanded ACA tax credits that provided subsidies for those marketplace plans. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act extended those expanded tax credits beyond the COVID-19 pandemic through December 2025. But the Budget Reconciliation Act of 2025 failed to extend those credits beyond the end of the year. Despite Congressional Democrats pushing to extend the credits during a late 2025 government shutdown, they have still not been extended to date. While Congress continues as of this writing to debate the issue, the open enrollment period for 2026 healthcare coverage has passed and most participants in ACA plans have seen steep increases in their premiums. According to an analysis by the healthcare research nonprofit KFF, premium costs for ACA enrollees are rising by an average of 114% for 2026. One analysis of the impact of the premium increases has suggested that nearly 5 million Americans will drop their healthcare coverage for 2026.

What is the likely bottom-line impact of these 2025 legislative actions on American death and disease rates? Researchers from the Yale School of Public Health have recently published estimates based upon simulations they had developed previously to project excess mortality associated with revisions to healthcare policy. They use the Congressional Budget Office estimate that 7.7 million Americans will become uninsured as a result of the Medicaid cuts. In addition, they assume that another 5 million Americans will forgo coverage due to the ACA tax credit terminations. They assume furthermore that healthcare for children and seniors will be minimally affected, so that most of these insurance losses are for individuals in the 19-64 age group. The Yale group’s estimates for excess annual mortality and excess incidence of uncontrolled common chronic diseases are summarized in Fig. II.6.

The estimates in Fig. II.6 are based only on the direct impact of the loss of health insurance. As we have argued above, the loss of vulnerable rural hospitals and healthcare providers will provide an indirect amplification of these impacts in rural areas, especially in red states. The loss of Medicaid support for some pregnancies and births will add further to the mortality rate. Yet an additional impact arises from another provision of the 2025 Budget Reconciliation Act, which repeals CMS minimum requirements for nursing home staffing. Implementation of the CMS rule was anticipated to prevent about 13,000 annual senior deaths. Including all of these effects, it is likely that 2025 legislative actions by the Republican-controlled Congress will lead to 40,000 or more excess preventable American deaths per year. Extrapolating from recent (pre-COVID) trends, it is likely that the excess death rate in Republican counties will be at least 5% above the national average and that in Democratic counties will be at least 5% below the national average. To put these estimates in perspective, the current annual number of deaths in the U.S. from all causes is about 3 million. So the 2025 legislative changes are likely to cause a 1-2% increase in the all-cause mortality rate, whereas the COVID pandemic caused about a 13% temporary increase.

III. cuts to scientific and medical research

FY2025 funding cuts:

In the second Trump administration’s initial frenzy to eliminate what they baselessly label as “waste, fraud, and abuse” in federal spending, they have aggressively targeted funding of scientific and medical research. The cuts that most directly affect Americans’ health are the ones made, with full participation by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). A May 2025 report from the minority staff of the Senate’s Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee has documented how the administration decimated medical research during its first three months in office, by rescinding or withholding funds that had been previously approved, terminating and failing to renew research grants, and drastically cutting HHS staff.

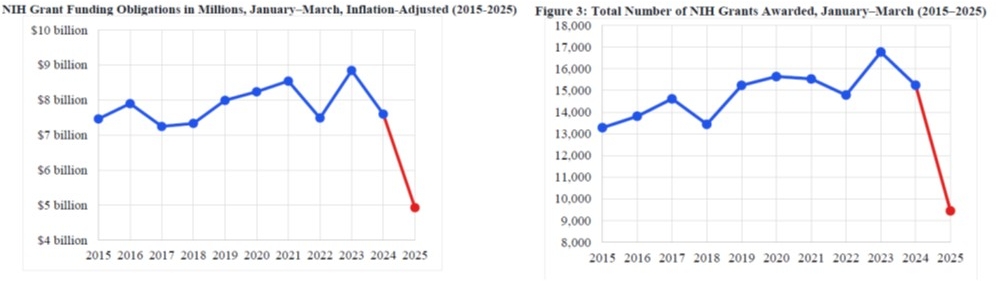

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) are the largest funder of biomedical research in the world. NIH-funded research has been central to many of the greatest discoveries and innovations in disease treatment and prevention made over the past half-century. But during its first three months the Trump administration cut NIH funding by 35% or $2.7 billion and the number of NIH grants awarded by 37%, as illustrated in Fig. III.1. By June 2025, those cuts grew to a total of $8 billion. According to Patricia LoRusso, past President of the American Association for Cancer Research, these cuts “have led to canceled research projects, halted clinical trials, hiring freezes, funding disruptions, and even growing pressure on scientists to adjust how they frame their work.”

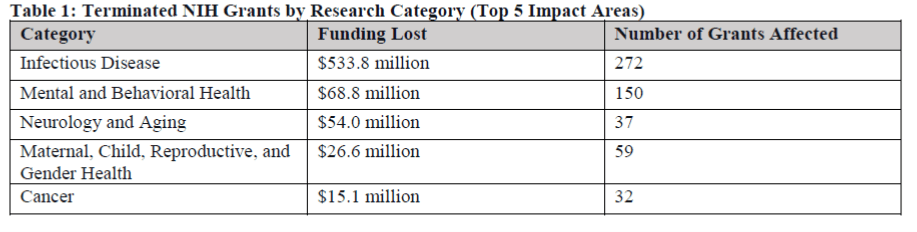

Existing NIH grants have been terminated without obvious regard for the importance of the research to the health of Americans, the review ratings of the proposals, or the past successes of the researchers involved. The five areas most impacted by the terminations are indicated in Fig. III.2. Terminated grants included a cancer research center at Columbia University, an infectious diseases clinical research consortium, research aiming at improving prevention and mitigation of Alzheimer’s disease, training of young researchers in cardiovascular and pediatric diseases, among many, many more. In addition to the terminated external grants, NIH laboratories studying Alzheimer’s disease and aging, prenatal and fetal medicine, and sickle cell disease have been shut down.

The terminated grants in cancer research indicated in the bottom row of Fig. III.2 represent only a small fraction of the cuts to cancer research. Despite Trump’s having campaigned on a promise to “cure cancer,” funding for the National Cancer Institute was cut by 31% (or $350 million) during the first three months of 2025. Later cuts decimated one of the most promising avenues for cancer research, namely, the use of mRNA vaccines for personalized immunotherapy. This is the type of vaccine that was used to end the COVID-19 pandemic. mRNA vaccines can be gene-edited to train the body’s immune system to attack specific types of proteins. In the case of COVID, the targeted proteins were the spike proteins surrounding the SARS-CoV-2 virus. If cancerous cells in a patient’s body are discovered early enough and analyzed, individualized mRNA vaccines can be produced to target specific proteins found exclusively in that patient’s cancerous cells. Clinical trials had begun to test mRNA vaccine treatments of melanomas, solid tumors, non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, and ovarian cancer.

Despite their great promise for treatment of cancers, as well as for prevention of various infectious diseases, RFK, Jr. announced on August 5, 2025 the cancellation of nearly $500 million in grants and contracts for research on health applications of mRNA techniques. RFK, Jr. and the Director of NIH, Jay Bhattacharya, offered lame excuses for their action. Kennedy claimed that mRNA vaccines “encourage new mutations [of targeted viruses]and can actually prolong pandemics as the virus constantly mutates to escape the protective effects of the vaccine.” This is nonsense. Viruses often mutate to escape treatment by any vaccine; the mRNA vaccines are particularly effective because they can be gene-edited quickly to track those mutations, as was done in the case of COVID. Bhattacharya claimed that the funding was being ceased because mRNA COVID vaccines had “failed to earn the public’s trust,” apparently ignoring the fact that 94.3% of the most at-risk Americans over 65 years of age had completed two doses of the original COVID vaccines, which were dominated by the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines. But since the early days of the COVID vaccines, Kennedy, Bhattacharya, and others have tried their best to destroy public trust in mRNA techniques by spreading misinformation. We wonder how many Americans who voted for Trump thought they were voting for drastic reductions in cancer research.

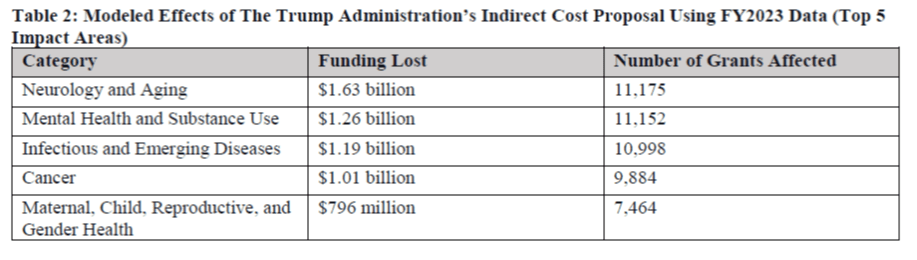

Beyond these already drastic cuts to biomedical research, the Trump administration proposed in February 2025 to limit indirect costs for federally funded research to 15% of the direct costs. The indirect costs cover all the infrastructure hardware and staff essential to carry out cutting-edge research in clean, forefront laboratories, including utilities, security, servicing computers, and for biomedical research in particular, animal care, biosafety, biological sample storage facilities, and so forth. Traditional negotiated indirect cost rates range from about 25% to as high as 60% of the direct costs, depending on the facilities and the demands of their needs. If the indirect cost cap were applied to NIH grants, it would result in well over an additional $4 billion in funding loss and render certain long-term research projects unsustainable. In the Senate Health Committee minority staff report the impacts were estimated in an exercise applying the cap to all NIH grants awarded in FY2023. Some of those impacts are summarized in Fig. III.3.

An indirect cost cap would, in principle, affect all federally funded research. As soon as the Trump administration proposal was announced, three separate coalitions of universities, medical organizations, and Democratic-led states filed suit in February 2025 to stop the proposed cap from being implemented. While the litigation continues, courts have so far barred the administration from imposing the cap. In April a judge in the Federal District Court in Massachusetts permanently barred the administration from imposing the cap, and that decision has just been upheld by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First District. In the Appeals Court decision Judge Kermit V. Lipez noted that “Congress went to great lengths to ensure that N.I.H. could not displace negotiated indirect cost reimbursement rates with a uniform rate.” It is likely that the case will be appealed by the administration to the U.S. Supreme Court.

FY2025 Staffing Cuts:

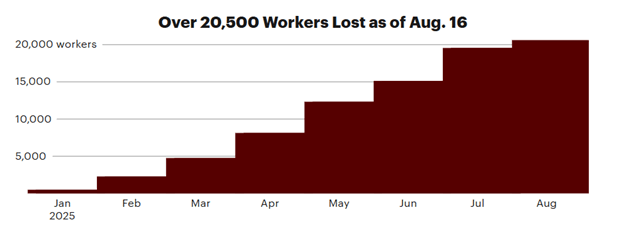

The ability of HHS staff to process research grant applications, to oversee ongoing biomedical research, and to participate in research themselves has been further deteriorated by massive and ill-considered firings within HHS. While HHS itself has been coy about the number of departures, ProPublica carried out a detailed analysis in August 2025. As of that date, there had been 20,500 departures from the Department, representing 18% of the total HHS workforce. As part of the Elon Musk-led attempt to instill efficiency by more-or-less random cuts to the federal workforce, some 10,000 HHS employees had taken incentives to leave the Department, while another 10,000 or so were fired or retired. The buildup in departures is quantified in Fig. III.4. ProPublica notes that: “The analysis is an undercount — it doesn’t include the hundreds or even thousands of workers who have received layoff notices but remain on administrative leave.”

As the ProPublica report notes, “Thousands of critical employees – including [more than 3,000] scientists and front-line health staff – have been pushed out, raising questions about how the agencies will continue their vital work.” The cuts include 21% of the staff in the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), including 900 scientists and health experts, along with over 500 regulators, investigators, and compliance workers. Over 3,000 workers have departed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), where a third of them worked as scientists or in healthcare roles. And NIH staff has been reduced by 16%, with more than 7,000 departures. The impacts of some of these cuts will be discussed in Section V, while we will concentrate on the impacts on biomedical research here.

One of the scientific program specialists who was laid off from NIH, Anna Culbertson, notes that many of the cuts were to “the people who deliver the grant funds, the people who are in charge of the funds and reviewing the funds. The consequence of grant funding delays is that some experiments and trials that take years may have to be restarted.” As a result, over and above the thousands of NIH grants that were terminated, even many grants that survived saw long delays in actually receiving funding. As a result of the terminations and delays, a number of universities have been forced to pause research, lay off staff, turn away students, and freeze faculty hiring.

Areas particularly hard hit are NIH institutes focused on mental health, aging, and infectious diseases, each of which lost 30% or more of the staff responsible for grant approvals and funding. For example, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), which was led by Dr. Anthony Fauci in past administrations, has lost 17% of its workforce overall, including the Director and many senior officials, despite the critical role that Institute has played historically in funding and participating in research regarding HIV/AIDS and COVID, both areas where RFK, Jr. holds anomalous opinions. When the next pandemic arrives, the NIAID cuts will come back to haunt Americans.

The ProPublica report notes that “more than 1,050 scientists, physicians and public health specialists — many of whom were conducting research and disease surveillance — have left or been pushed out of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention alone since January.” The entire team tracking maternal and infant health outcomes has been placed on administrative leave, despite the fact that both maternal and infant mortality have been on the rise in the U.S. since the adoption of draconian anti-abortion laws in many Republican-led states. Despite RFK, Jr.’s publicly stated goal to “end the chronic disease epidemic” in the U.S., 20% of CDC’s chronic disease center employees have been cut, nearly half of whom were scientists and public health workers. The cuts include 35% of the CDC division that focuses on preventing heart disease and strokes. And in the center that focuses on smoking and health, it appears that only a single federal worker is still employed, even while research on the dangers of vaping and e-cigarettes is critical.

At FDA, the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research has been severely impacted by the cuts. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Center played the central role in funding the research and overseeing the manufacture and rollout of safe, effective COVID vaccines. The Center also in the past conducted its own research on vaccine development. The Center’s former director, Peter Marks, resigned under pressure in March 2025, citing “an unprecedented assault on scientific truth.” HHS spokespeople responded by saying that Marks had no place at the agency since he did not support “restoring science to its golden standard.” The “gold standard science” favored by RFK, Jr. is fool’s gold, it has little to do with actual science and puts Americans’ health at enormous risk.

Proposed FY2026 cuts:

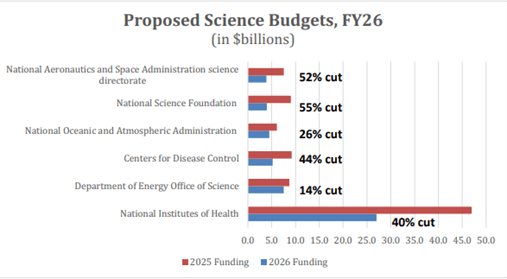

Donald Trump and his Director of the Office of Management and Budget, Russell Vought, made perfectly clear in the President’s FY2026 proposed budget that the assault on science was intentional. The proposed budget called for draconian cuts to funding for all of the major federal research funding agencies, as summarized in Fig. III.5. Compared to the FY2025 appropriations, which were decided before Trump took office, the President’s budget proposed cutting funding for the NASA science directorate by 52%, the National Science Foundation (NSF) by 55%, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) by 26% (eliminating all of its climate monitoring and research), the NIH by 40%, the CDC by 44%, and the Office of Science at the Department of Energy (which funds all the national laboratories) by 14%.

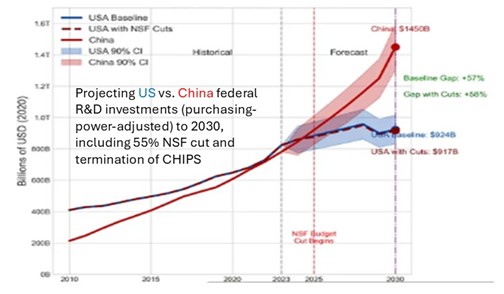

Such cuts, if enacted, would basically cede world research leadership to China. China’s annual expenditures on R&D have been increasing rapidly and have essentially equaled those in the U.S. in terms of purchasing power within the two countries. Figure III.6 shows projections to the end of this decade that take into account the proposed 55% cut to NSF funding and the proposed termination of the 2025 CHIPS Act that aimed to limit U.S. technology exports to China. Those acts alone would likely lead to a 50% Chinese lead over the U.S. by 2030 in federal investments in R&D. The proposed cuts to the other research funding agencies would make the comparison even much worse for the U.S. Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson put it this way: “If a foreign adversary snuck into our Federal budget and cut science research and education the way we’re cutting it ourselves – strategically undermining America’s long-term health, wealth, and security – we would likely consider it an act of war.”

Fortunately, enough members of Congress understand the folly of decimating R&D that has driven U.S. economic growth since the end of World War II. The FY2026 budget is still under development in Congress but the signs for restoring science funding are quite positive. In recent days, the Senate Appropriations Committee has released a bipartisan package of bills that reverse most of Trump’s proposed cuts to science funding and the package was subsequently approved by the House of Representatives. Compared to FY2025 appropriations, for example, the Senate package includes flat funding for NOAA, a 1.9% increase for the DOE Office of Science, a 1.6% cut for NASA, and a 2.3% increase for the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

NSF funding proposals are substantially different in the Senate and the House and will need to be considered in a Conference Committee of the two houses: the Senate has proposed a decrease of only 0.7% from FY2025 appropriations, while the House has proposed a decrease of 23%. While both numbers are much better than Trump’s proposal, an important consideration that hangs in the balance is funding to continue the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado. NCAR is home to hundreds of scientists who have been, since 1960, providing critical research on ways to improve weather and climate forecasting, air quality, and understanding of the impacts of greenhouse gas accumulations in the atmosphere on Earth systems. Each research focus area at NCAR bears significantly on the health and welfare of Americans, which will suffer if NCAR is terminated.

The health of Americans is most impacted by funding for the HHS agencies. The Senate proposal includes an overall 1% increase over FY2025 for NIH and includes language prohibiting the Trump administration from making changes to negotiated indirect cost structure in NIH grants or from restructuring NIH’s 27 institutes and centers, without collaborating with Congress. The House version also would fund every one of the 27 NIH institutes and centers, most at flat funding compared to FY2025. The House proposal would cut the Center for Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases by 9%, the Office of the NIH Director by 8%, and the Center for Neurological Disorders by 2%. At the same time, it would increase funding by 2% for the Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities. The largest difference between the Senate and House proposals for NIH concerns the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-Health), for which the Senate proposes flat funding and the House proposes a 40% cut. The House also proposes a 41% cut to CDC funding, only slightly better than the President’s proposed 53% cut, while the Senate proposes only a 1% cut compared to FY2025.

Litigation:

While the generally positive details of FY2026 Congressional science funding have yet to be finalized, serious questions remain about the actual impact Congressional decisions will have on HHS spending. The Department’s spending during calendar year 2025 fell far short of the appropriations. In principle, the President is required by the 1974 Impoundment Control Act (ICA) to request and receive explicit Congressional approval for withholding or delaying the expenditure of funds appropriated by Congress. In August 2025, the General Accounting Office (GAO) indeed found that HHS had violated the ICA (one of several violations noted during 2025 by the GAO): “Based on publicly available evidence and the lack of any special message pertaining to NIH funds, GAO concludes that NIH violated the ICA by withholding funds from obligation and expenditure.”

A number of the cuts executed or attempted by NIH during FY2025 have led to lawsuits that are still ongoing. As we noted earlier, a federal appeals court has in January 2026 upheld a lower court ruling that blocks the Trump administration from imposing a cap on indirect funds for NIH grants, since Congress has previously negotiated those indirect rates. A separate suit was filed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and various organizations representing medical researchers over the NIH’s refusal to even consider certain grant applications. That action followed a Trump administration early decision to disallow research in areas to which it was ideologically opposed, such as climate change, diversity, equity and inclusion, pandemic preparedness, and gender ideology. The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld a decision that that general policy was arbitrary and capricious, in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act.

But that policy had led the NIH to terminate or fail to even evaluate grants “that funded everything from research into antiviral drugs to the incidence of prostate cancer in African Americans.” The Supreme Court upheld a District Court decision that the grant terminations based on those ideological considerations were voided, but the Court argued that actually restoring funds to those groups would have to be handled in a separate case filed in a different court. Meanwhile, just before the start of 2026 the NIH did reach a settlement concerning the grant applications it had not even bothered to evaluate, since the ideological guidelines had already been found by the Supreme Court to be illegal. The government now agrees to evaluate each of the dismissed applications “in good faith,” while the researchers affected accept that “Nothing in this stipulation commits NIH to ultimately award any specific Application.”

However, the drastic staffing cuts made during 2025 at NIH pose a serious challenge for the institutes to evaluate and actually disburse funds in a timely fashion not only for those previously ignored FY2025 grant applications but also for all the new applications that will be submitted in light of the encouraging Congressional actions on FY2026 funding. It appears to us quite likely that the Trump administration will actually spend what Congress appropriates for biomedical research only as it is forced to by further time-consuming litigation. Furthermore, evaluations of NIH proposals are likely to be considered by advisory committees to which RFK, Jr. appoints members who share his anomalous opinions about vaccines and the causes of Americans’ chronic diseases.

Likely impacts:

It is very hard to guesstimate how many preventable American deaths may result from failures to fund many biomedical research applications. Who knows what breakthroughs may be missed in treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, or other chronic diseases? But experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic do provide some basis for guessing what damage RFK, Jr.’s opposition to vaccines may cause. The deep staffing cuts at FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, which played such a crucial role in the COVID vaccine rollout, combined with RFK, Jr.’s termination of grants and contracts on mRNA vaccine research, make the U.S. much less prepared for the next pandemic.

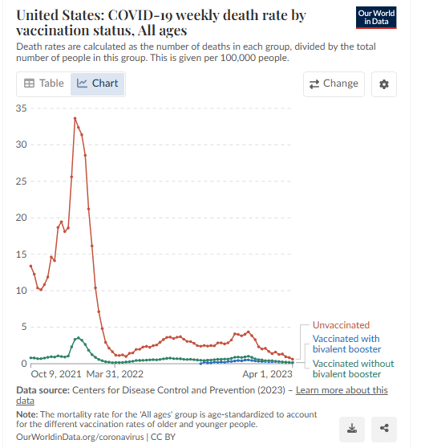

How many American deaths from COVID were avoided by the rapid development of mRNA vaccines to limit the virus’ spread? Within a year of the vaccines’ first availability there was a tremendous surge in COVID cases caused by the Omicron variant of the virus. As shown in Fig. III.7 the death rate of unvaccinated Americans during the Omicron surge was an order of magnitude higher than that of vaccinated individuals. Most of the deaths occurred among unvaccinated seniors (age 60 and above), who represented only a small fraction of all U.S. senior citizens. From data such as these, one can produce reasonable estimates of the number of lives saved by the rapid vaccine development. Lives saved include not only vaccinated people but also the unvaccinated who are exposed to less viral spread thanks to the vaccinated.

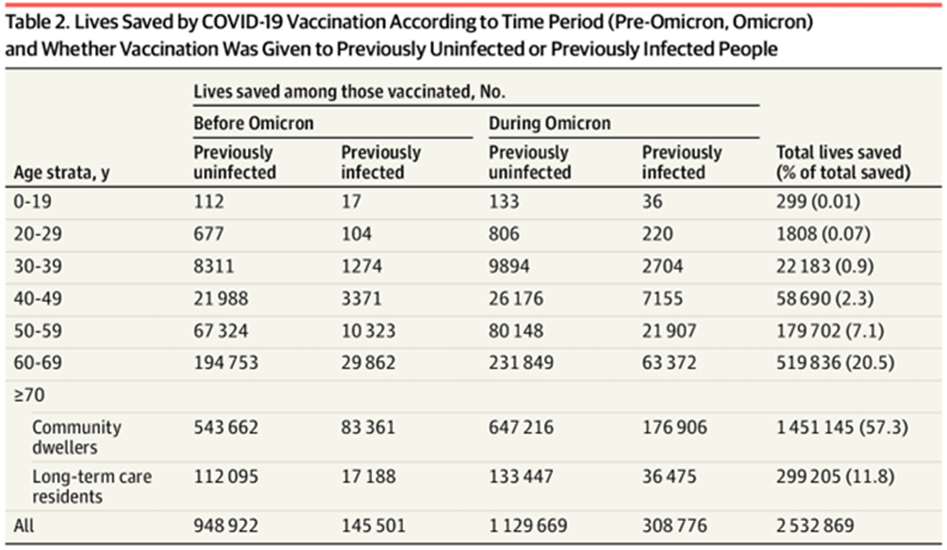

The most complete investigation of lives saved globally by the COVID vaccines has been published in July 2025 in the Health Forum of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Groups from Stanford University and two universities in Rome, Italy used publicly available worldwide data on infection rates, vaccination rates, and the vaccines’ effectiveness in reducing mortality rates. “Data were stratified by age, pre-Omicron and Omicron periods, vaccination before and after infection, and long-term care settings...” The results of their analysis for lives saved globally are shown in Fig. III.8. They found that: “more than 2.5 million deaths were averted (1 death averted per 5400 vaccine doses administered). Eighty-two percent were among people vaccinated before any infection, 57% were during the Omicron period, and 90% pertained to people 60 years or older…An estimated 14.8 million life-years were saved (1 life-year saved per 900 vaccine doses administered).”

In order to make this estimate applicable within the U.S. alone, we can assume that the estimate of one death averted per 5400 vaccine doses administered applies as well to Americans. Approximately 660 million COVID-19 doses were administered in the U.S. between January 2021 and December 2022. Then, from the Ioannidis, et al., analysis, some 120,000 American lives were saved, or just about 10% of the total American deaths from COVID-19. Note that this is an underestimate because the analysis in Fig. III.8 includes only lives saved among the vaccinated, while some lives among unvaccinated people would also have been saved because of reduced spread of the virus. This estimate is then in rough agreement with some other estimates, but is far smaller than the estimate of more than 3 million lives saved reported by Dr. Peter Hotez to an Oct. 2024 House committee hearing. Clearly, these estimates do not represent an exact science. Nonetheless, they give us some basis to guess that delaying the development of vaccines to treat a new viral pandemic, due to policies pursued by RFK, Jr., would likely place hundreds of thousands to millions of American lives at risk. And the cost in life-years may be far worse than estimated for COVID because the next pandemic may prove more deadly to young people (as was the case for the 1918 Spanish flu) than to seniors.

— Continued in Part II —