January 6, 2024

I. Introduction

In the spring of 1989 not only the science world, but also the entire world, was rocked by the bombshell announcement that two chemists, Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann, had achieved fusion in an electrochemical cell at room temperature. This announcement was sensational because room-temperature nuclear fusion seemed to contradict everything we knew about the fusion process. Furthermore, it was claimed that the amount of energy released in these fusion reactions would be sufficient for rapid development as a commercial source of energy. If the announcement was confirmed, it would solve the world’s issues with fossil fuels and climate change. Cold fusion would provide a limitless energy source that produced no greenhouse gases. Nations would not have to resort to drilling wells and refining oil and gasoline to access cheap energy. The uses for this technology would be manifold and would revolutionize our culture. No wonder that the cold fusion ‘discovery’ was front-page news on papers and magazines around the world. Because the experimental setup was so simple and the basic ingredients so easily accessible — one needed to be able to afford deuterated water and to obtain Palladium (Pd) electrodes, but this was nothing compared to the billions spent on major technological developments — researchers from all over the world rushed to cobble together electrolytic cells to test the Pons-Fleischmann claims.

Alas, the cold fusion discovery touted by Pons and Fleischmann never materialized. We will document this in the sections to come, where we will review attempts to verify or debunk the cold fusion claims. Also, since this is a post in our series on “fraud in physics,” we will try to determine whether cold fusion claims represented fraud, or whether they were simply the result of massive incompetence on the part of advocates for cold fusion. Pons and Fleischmann were chemists and not physicists. However, because they claimed to have observed a physics process, nuclear fusion, we include the cold fusion saga in our series on fraud in physics.

In Section II of this post, we will review efforts to produce “normal” fusion on Earth. In particular, we will discuss why scientists are attempting to produce plasmas at incredibly high temperatures and densities. The enormous temperatures and densities required for ‘hot’ fusion will underscore why the announcement of room-temperature nuclear fusion was such a shock to the ‘mainstream’ science community. In Section III, we will discuss the events leading up to the press conference on March 23, 1989, when Pons and Fleischmann claimed to have produced nuclear fusion in an electrolytic cell. We will also cite a few of the many groups that announced ‘confirmation’ of Pons and Fleischmann’s claims. In Section IV, we will follow the subsequent experiments that failed to find any evidence for cold fusion. In Section V we will summarize the brief, contentious and ultimately sad history of cold nuclear fusion.

In preparing this post, we have relied on two books that summarized the history of the cold fusion craze. The first is Bad Science: The Short Life and Weird Times of Cold Fusion, by science journalist Gary Taubes (see Fig. I.1). The second is Too Hot to Handle: the Race for Cold Fusion, by our nuclear physics colleague Frank Close. We also provide a brief summary of articles on cold fusion at the end of this post (there are hundreds if not thousands of these articles). The Department of Energy (DOE) committee report on cold fusion cites many of these articles, the Wikipedia entry on cold fusion lists several others, and the Taubes and Close books include additional references.

Figure I.1: Cover of the book Bad Science, by science journalist Gary Taubes. This book chronicles the history of the cold fusion saga.

II. ‘Normal’ Nuclear Fusion

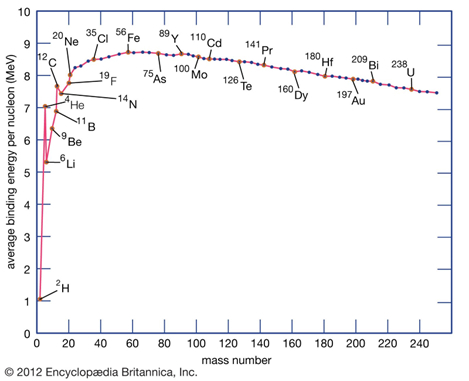

In order to assess the claims of room-temperature nuclear fusion, we will briefly review normal, or ‘hot,’ nuclear fusion. Nuclear fusion is the energy source that powers stars. Here we present a very brief overview of our blog post on the future of nuclear power. In the fusion process, light nuclei combine or ‘fuse’ to produce a heavier nucleus. Because the higher-mass nuclei have higher nuclear binding energy, when light nuclei with lower binding energies fuse to form heavier nuclei with larger binding energies, energy is released in this reaction. Figure II.1 shows the average nuclear binding energy per particle, in millions of electron-volts (MeV, a unit of energy) vs. the mass number (the number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus). Note that Helium-4 (4He, where the superscript denotes the mass number, 4 for Helium-4 with two protons and two neutrons in the nucleus) has an anomalously high nuclear binding energy. Thus, fusion of hydrogen or its isotopes leading to Helium-4 leads to a large change in binding energy, and will release a tremendous amount of energy. The challenge is getting the reaction to proceed at high enough rates in the laboratory to provide a reliable energy source.

Figure II.1: The curve of binding energy. Average binding energy per particle (in MeV) vs. mass number. Reactions that lead to increased binding energy release energy; in the fusion process, low-mass nuclei join or fuse to form higher-mass nuclei with higher binding energies.

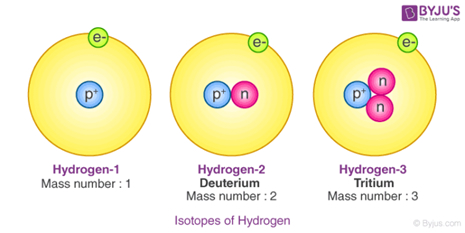

Figure II.2 shows the three isotopes of hydrogen. All of these contain a single proton in the nucleus and one electron in the neutral atom. The Deuterium nucleus contains a proton and one neutron in the nucleus, while Tritium has one proton and two neutrons in the nucleus. All three of these atoms have nearly identical chemical properties. Tritium is unstable; it decays with a half-life of 12.33 years.

Figure II.2: The three isotopes of hydrogen. All three have one proton in the nucleus and one electron. Deuterium has a proton plus a neutron in the nucleus, while the Tritium nucleus has a proton plus two neutrons.

In the Sun and other stars, four protons combine in a series of nuclear reactions that lead to one 4He nucleus, plus a number of other particles (positrons and neutrinos) and gamma rays. The process releases an enormous amount of energy, which is eventually emitted as electromagnetic radiation by the Sun. In order for these nuclear reactions to proceed, the protons need to be close enough for the strong nuclear force to hold them together. The strong nuclear force acts only when the charged particles are almost touching one another. However, protons and other atomic nuclei are positively charged, and repel each other by the electric Coulomb force which is repulsive for like charges. The Coulomb force becomes larger as the protons approach one another. To get them close enough for the nuclear force to bind them together, the light nuclei must have very large kinetic energies to overcome their Coulomb repulsion. And the matter needs to be sufficiently dense for nuclear fusion to occur at high enough rates to produce appreciable energy.

In the central region of stars, the gravitational attraction from this gigantic ball of gas provides an enormous pressure, in the center of the Sun some 260 billion times the atmospheric pressure on the Earth’s surface. The density at the center of the Sun is 150 times that of water, and the Sun’s central temperature is 15 million Kelvin (15 million degrees Celsius above absolute zero) as the result of enormous gravitational energy converted to heat. At these incredible temperatures and densities, protons are moving sufficiently fast that they can overcome the Coulomb repulsion, and they are sufficiently close to other protons that they are able to fuse to form Helium-4.

On Earth, we are unable to reproduce the incredible pressures at the center of the Sun. However, scientists have devised two different ways to produce conditions under which nuclear fusion will occur. Both of these methods tend to use a fuel mixture consisting of Deuterium and Tritium, which can be made to fuse sufficiently often when one reaches a temperature of at least 100 million Kelvin. Attaining and maintaining such enormous temperatures in the fuel mixture, without melting the apparatus in which the fuel is confined, are the daunting technical challenges facing thermonuclear fusion on Earth. The first of these processes is called inertial confinement fusion. In this reaction, a spherical pellet containing Deuterium and Tritium is bombarded on all sides with X-rays produced by incredibly powerful laser beams. A burst of energy from the lasers causes the pellet to implode. If the laser beams have just the right characteristics, the implosion will cause the temperature and density at the center of the sphere to reach conditions where nuclear fusion takes place, through the D-T reaction

2H + 3H –> 4He + n + 17.6 MeV (1)

The reaction in Eq. (1) produces enormous amounts of energy but, unlike nuclear fission processes, does not produce any long-lived radioactive waste. It also presents no danger that a “runaway” reaction could produce explosions and meltdowns as in the fission process, where large amounts of radioactive materials might be released into the ecosphere. Thus, if nuclear fusion can be made into a commercially viable energy delivery system, it would solve many of the problems associated with fossil fuels or nuclear fission reactors.

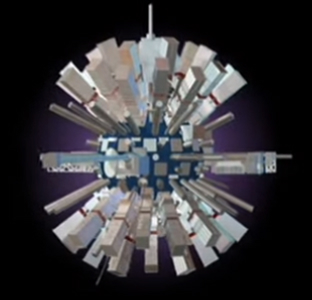

The D-T fusion reaction releases an incredible amount of energy (17.6 MeV). The trick in inertial confinement fusion is to arrange that the energy of the light from all 192 high-power lasers at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) focus just right in order to ignite the fuel pellet. The central temperature and density must be sufficiently high so that fusion occurs. Figure II.3 shows the array of high-powered lasers at NIF, which is located at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California.

Figure II.3: The laser setup at the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. The 192 lasers produce X-rays that bathe a pellet containing a D – T mixture that implodes and initiates nuclear fusion when sufficiently high temperatures and densities are reached in the center of the pellet.

Experiments at NIF have been carried out for decades. For the first time, on Dec. 5, 2022, the NIF experiment achieved ignition with an output energy from nuclear fusion events that was larger than the input energy delivered to the fuel pellet from the lasers, but was still only about 1% of the total electrical energy needed to power the lasers for the experiment. However, we are still several decades away from a point when one could envision inertial confinement fusion becoming a conventional power source that could compete with energy from fossil fuels.

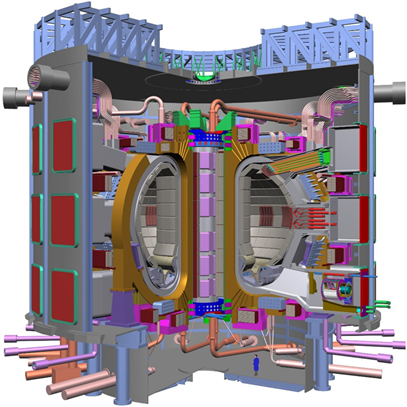

The second type of fusion that is being pursued is called magnetic confinement fusion. In this process, a hot plasma containing D and T fuel is confined by a complicated array of electromagnets inside a doughnut-shaped vacuum region in a machine called a Tokamak. Very high electric and magnetic fields confine and heat the plasma. The trick is to produce incredibly high temperatures and densities in the center of this confinement region. The temperatures are comparable to those in inertial fusion. However, the density of the plasma in the center of the Tokamak is much smaller than at the center of an inertial fusion fuel pellet. Thus, the plasma in a Tokamak must be held for a considerably longer period of time than in inertial fusion.

The world is pooling its efforts for magnetic confinement fusion in a multi-national effort called the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor or ITER. This is a collaboration of 35 countries that are building the world’s largest magnetic confinement fusion facility. Figure II.4 shows a schematic picture of the ITER facility in France (for scale, note the figure of a man in front of the reactor). Construction of ITER was scheduled to be completed by 2025 and attainment of its power production goal was proposed for 2035. However, COVID and some technical challenges have caused the schedule to be revised. As of Dec. 2023, the revised schedule has not been announced, but it has been stated that delays in the schedule will be “substantial.” ITER goals are to produce 500 MW (Mega-Watt, a unit of electric power) output for 50 MW input needed to heat the plasma in the first place. This goal would be substantially beyond the so-called “break-even” point. However, even if ITER eventually meets its stated energy goals, there would still be decades worth of technology development before fusion power could be envisioned to compete commercially as a conventional energy source with fossil fuel, solar or wind power, or with a new generation of nuclear fission reactors.

Figure II.4: Schematic figure of the Tokamak magnetic confinement fusion power research reactor being built at the multi-national facility ITER, in France.

The nuclear fusion power projects that are currently being built and tested require enormously high temperatures, pressures and densities for nuclear fusion to take place. And even if fusion occurs, it will require incredible advances in technology for either inertial confinement fusion or magnetic confinement fusion to become competitive with conventional energy sources. These projects have now been ongoing for roughly 50 years, with many years yet to go. The current demonstration projects will cost many billions of dollars, and turning these into reliable energy sources will take billions more. This is the background to the claims by Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann that for a few thousand dollars, they produced an electrochemical process where nuclear fusion was claimed to occur at room temperatures, and that this ‘cold fusion’ process could almost instantly be converted into commercial generation of energy.

III. The Bombshell: ‘Cold’ Nuclear Fusion at Room Temperatures?

Stanley Pons was a chemist at the University of Utah who specialized in the field of electrochemistry. He had obtained his Ph.D. degree in 1978 at the University of Southampton in England. There he met Martin Fleischmann, a chemist at Southampton. Fleischmann was a distinguished chemist; he held the Faraday Chair of Chemistry at Southampton and had been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Fleischmann had retired from Southampton in 1983 but continued to do research. In early 1989 he was collaborating on electrochemistry experiments with Stanley Pons at the University of Utah. In the mid-1980s, Pons and Fleischmann began carrying out experiments using electrolytic cells with a Palladium cathode. In those cells, the hydrogen atoms in normal water (H2O) had been replaced with deuterium (D2O).

Figure III.1: Stanley Pons (L) and Martin Fleischmann, the two chemists who claimed in March, 1989 to have observed nuclear fusion at room temperatures in an electrolytic cell.

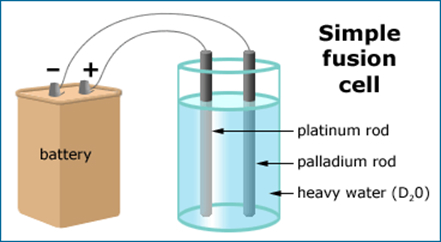

A schematic diagram of the electrolytic cells used by Pons and Fleischmann is shown in Figure III.2. A Platinum rod serves as the anode in this cell while a Palladium rod serves as the cathode. The rods are connected to the terminals of a DC battery and are submerged in a solution of water with a small amount of Lithium. In this liquid, normal water is replaced by heavy water, D2O. The entire assembly is held in a jar.

Figure III.2: Schematic picture of the fusion cell used by Pons and Fleischmann. A platinum rod is the anode while a Palladium rod is the cathode. The rods are connected to the terminals of a DC battery, and the rods are immersed in a solution of water and Lithium, where normal water is replaced by heavy water (D2O).

When Pons and Fleischmann operated their cells, they found that for long periods of time, the cells would operate normally. However, for periods of time after that, they reported that some cells would produce heat. Those cells would heat up fairly rapidly, and would continue to produce ‘excess heat’ for some time (this varied greatly from one cell to another). One morning, when the person operating the cells (this was Stan Pons’ son) returned to the lab, he discovered that there had been an explosion overnight. The explosion destroyed a cell, the battery and the lab hood, and gouged a large 4-inch-deep hole in the concrete floor of their lab. At this point, Pons and Fleischmann believed that their cells were producing massive amounts of heat, sufficient to explode and produce a large hole in concrete. They concluded that the only explanation that would produce this outcome was that the cells were producing energy through nuclear fusion of the deuterium nuclei.

Afterwards, chemists who studied electrolytic reactions recounted that lab explosions were not all that uncommon. The combination of large batteries and electrochemical processes could produce large explosions from chemical reactions alone. In fact, a group trying to replicate the Pons-Fleischmann experiments had a chemical explosion in an electrochemical cell that killed researcher Andrew Wiley in 1993. However, the lab explosion seemed to convince Pons and Fleischmann that they were producing conditions where nuclear fusion was occurring at room temperatures.

Pons and Fleischmann realized that no one had ever produced nuclear fusion at room temperatures. They knew that, if true, their results would bring them fame and fortune. If significant amounts of energy from fusion could be produced in their cells, this could be worked into commercial fusion energy production. Their electrolytic cells could replace conventional fuels as energy sources. This would result in cheap power with no greenhouse gases (as was the case with fossil fuel burning) or long-lived radioactive by-products (as occurs with nuclear fission reactors). Pons and Fleischmann would almost certainly win the Nobel Prize for this discovery, and revenue from the patents for their process would make them, and their home universities, wealthy. So they worked feverishly to take data, and to determine the precise conditions that were necessary to produce the excess energy in these cells.

In the electrolytic cells used by Pons and Fleischmann, normal water (H2O) had been replaced with deuterated water (D2O). The two chemists claimed that their cell was producing energy through a process where two deuteron nuclei would ‘fuse’ and release energy. Fusion of two deuterons takes place in one of three reactions:

D + D –> n (2.45 MeV) + 3He (0.8 MeV) (2a)

D + D –> p (3.0 MeV) + 3H (1.0 MeV) (2b)

D + D –> 4He + γ (23.8 MeV) (2c)

In Eqs. (2), we give the final reaction products and their kinetic energies in units of MeV. When the two deuterons fuse, for a very short period of time, about 10-22 seconds, they produce an intermediate 4He nucleus. However, this nucleus nearly always decays into one of the two states in Eqs. (2a) and (2b). When two deuterons fuse, 50% of the time they produce a neutron plus 3He (Eq. 2a), and 50% of the time they produce a proton plus Tritium (Eq. 2b). The final state of a Helium nucleus plus a gamma ray, Eq. (2c), occurs only one time in a million. In Eq. (2a) the neutron is released with energy 2.45 MeV. Relative to ordinary chemical reactions, this is a gigantic amount of energy. In Eq. (2c), the energy of the gamma ray is 23.8 MeV.

When fast neutrons are produced in a nuclear reaction such as Eq. (2a), they can subsequently fuse with a proton to produce a deuteron, via Eq. (3).

n + p –> D + γ (2.22 MeV) (3)

In Eq. (3), the energy of the gamma ray produced from this reaction is 2.22 MeV. From Eqs. (2) and (3), we can see the tell-tale signs of conventional nuclear fusion of two Deuterons. If fusion was occurring at the rates estimated by Pons and Fleischmann from the heat produced in their cells (they claimed to be producing between 10 and 50 Watts of power from their cells), one should see copious numbers of neutrons and Tritium. For example, if nuclear fusion was producing one Watt of power, this should be accompanied by one trillion (1012) neutrons per second. Occasionally, Helium-4 should be produced via the mechanism of Eq. (2c). Fast neutrons that emerge from Eq. (2a) would sometimes fuse with protons to produce Deuterium via Eq. (3), accompanied by gamma rays with energy 2.22 MeV. So, if they were seeing heat production by nuclear fusion, Pons and Fleischmann should have detected significant numbers of fast neutrons, Tritium, Helium-3, Helium-4 and gamma rays of very specific energies.

The explosion in the Pons-Fleischmann lab convinced them that the energy released was too large for any known chemical reaction, and therefore must be a result of nuclear fusion. They sought funding support for their research from the Advanced Energy Projects (AEP) office of the Department of Defense. They contacted the head of the AEP office, Ryszard Gajewski. They informed Gajewski of their preliminary results and sent him a funding proposal. Gajewski sent the proposal out to various scientists to review. One of those reviewers was Steve Jones, a physicist at Brigham Young University.

The Role of Steve Jones in Cold Fusion:

Steve Jones was a logical person to review the Pons-Fleischmann proposal because he had worked in a related field. Jones had been doing research on muon-catalyzed fusion. Jones examined the possibility that in matter muons might initiate fusion reactions among Deuterium and Tritium nuclei. Muons are particles with properties extremely similar to those of electrons, except that the muon is 200 times more massive than the electron. Muons are unstable particles but can be produced in large quantities in accelerator facilities. It had been speculated that muons might cause fusion to occur by facilitating the formation of molecules in which two hydrogen isotopes were brought much closer together than in water or heavy water molecules. , Furthermore, it had been speculated that a single muon might catalyze many fusion reactions. If a single muon initiated enough fusion reactions, it could conceivably serve as a source for commercial fusion. However, so far Jones’ studies had never been able to produce enough muon-catalyzed fusion reactions to make commercial fusion a reality.

Figure III.3: Steven E. Jones, professor of physics at Brigham Young University and researcher of fusion reactions in electrolytic cells.

Shortly after receiving the proposal from Pons and Fleischmann, Steve Jones began to study electrolytic reactions using Palladium cathodes in solutions using deuterated water. This would later become a major point of contention between Jones, Pons and Fleischmann. Pons and Fleischmann believed that Jones had begun his electrochemical studies only after reading the proposal from the group at the University of Utah. If so, this would be a serious breach of scientific ethics. When scientists are sent proposals to review, they must specify that they will not use material in those proposals to inspire their own work. The fact that Jones, a physicist, was doing research in electrochemistry, and that he was investigating systems that were so similar to those of Pons and Fleischmann, looked really fishy.

On the other hand, colleagues of Jones stated that he had a reputation of being remarkably honest and straightforward. They could not believe that he would do anything so underhanded. When challenged later, Jones produced photocopies of his lab notebooks, showing that a couple of years earlier he had contemplated doing electrochemical studies. To Jones and his supporters, this proved that he was behaving ethically. However, Pons and Fleischmann felt that there was little evidence that Jones had carried out these studies earlier; and Jones’ new research did have a striking resemblance to the Pons-Fleischmann studies. In late January 1989, Steve Jones submitted his own funding proposal to Ryszard Gajewski at AEP. Unlike Pons and Fleischmann, who believed that the excess heat was a sufficient signal for cold fusion, Jones was looking for excess neutrons that would be produced by the reaction mechanism of Eq. (2a).

In retrospect, Jones and Pons-Fleischmann were discussing nearly identical electrochemical experiments, but they were talking about two vastly different outcomes. Pons and Fleischmann believed they were producing many Watts of electric power through fusion. On the other hand, in Jones’ experiments he claimed to see a couple of neutrons per hour. The experiments of Jones would never produce enough power for commercial cold fusion to be a reality. Assuming that fusion was taking place in the ‘normal’ way as described by Eqs. (2), Pons and Fleischmann should have been seeing a thousand trillion times more neutrons than Jones. But the vast difference in energy output claimed by the two groups was initially overlooked by many researchers and by most journalists.

A critical incident in the cold fusion saga occurred on February 2, 1989. Steve Jones intended to discuss his muon-catalyzed fusion research at a national meeting of the American Physical Society (APS) in early May of that year. The deadline for submission of abstracts to that meeting was Feb. 3, so on Feb. 2 Jones sent his abstract by overnight mail. However, Jones added two sentences at the end of that abstract: “We have also accumulated considerable evidence for a new form of cold nuclear fusion which occurs when hydrogen isotopes are loaded into materials, notably crystalline solids. Implications of these findings on geophysics and fusion research will be discussed.”

Somehow, Pons and Fleischmann heard of Jones’ abstract. They panicked, thinking something like – “Oh my God, Jones is going to scoop us on cold fusion!” They weren’t completely paranoid – once the APS abstracts were published, Jones could presumably have used that publication date to establish his priority in this “discovery,” as Pons & Fleischmann had not yet published anything on that topic. Pons and Fleischmann could see themselves being screwed by Jones – the fame and wealth, the Nobel Prize, the patents, all of this snatched from them by a scientist who had very possibly pirated their discovery. In order to understand the actions of Pons and Fleischmann from that date, one needs to view their behavior not from the point of view of rational scientific researchers, but from a panicked duo who were desperate to regain the priority of discovery (and all that accompanied it) from a competitor. Before learning of Jones’ abstract, Pons and Fleischmann believed that they were the only scientists onto this line of research. They envisioned taking data and firming up their conclusions for another 18 months before they would publish their ‘blockbuster’ papers. Now, however, they felt they had to immediately make a move.

The Utah scientists arranged a meeting between Pons and Fleischmann and Steve Jones. The meeting took place on March 6, 1989. The three scientists attended, together with University of Utah president Chase Peterson and BYU president Jeffrey Holland and a few other administrators. Both sides alleged that they were interested in a collaborative effort. Jones invited Pons and Fleischmann to bring their cells to him, where they could measure the number of neutrons being produced using Jones’ neutron detectors. Pons and Fleischmann never brought their cells to BYU. Utah president Peterson suggested that both sides agree to postpone making any public announcements until both sides were ready. At that time, they could make a joint announcement of their discoveries and simultaneously submit papers for publication. As part of this proposition, the Utah delegation asked Jones not to mention cold fusion in the abstract he had submitted to the APS meeting. Jones, however, refused this offer. Since Jones was seeing so few neutrons and saw no commercial applications from his research, he could not see why he should not make this announcement. Jones said, “We’ve been looking at this process for years now, and it’s just not an energy producer. If you could ever get enough energy to light a flashlight, I’d be extremely surprised.”

Eventually, the Utah and BYU groups agreed to hold a joint press conference announcing their discoveries. They also agreed to submit papers back-to-back to a prestigious journal (the chemists Pons and Fleischmann suggested submission to Nature, while Jones advocated for Physical Review Letters, the most prestigious physics journal). The joint public announcement would take place before April 3, which was the day that Steve Jones’ abstract would be published by the APS. But almost immediately following this meeting, Pons and Fleischmann decided to breach the agreement. First, they felt that Jones was trying to horn in on their big discovery. And second, they were nowhere near the point where they were ready to publish a paper. Until they heard of Jones’ work, they had planned to take data for another 18 months before publishing their results. After that meeting, both sides distrusted the other. And both sides were reluctant to state when they had begun research on cold fusion; each group felt that if they volunteered when they had begun their work, the other side would claim that they had started a year earlier and thus had priority for patent rights.

Over the next several days Pons and Fleischmann took data around the clock, trying to make an airtight case that they were seeing cold fusion. Together with graduate student Marvin Hawkins, they tried to amass enough data that their subsequent presentation would be convincing to the outside world. Pons and Fleischmann had purchased a neutron detector from the British Harwell Laboratory and given the amount of heat they claimed to be generating, they should have seen a massive flux of neutrons. But they were seeing no neutrons. Was something wrong with their neutron detectors or was D-D fusion in their cell occurring by a different process from the ‘standard’ physics model summarized in Eqs. (2)? Apparently, Pons and Fleischmann did not consider the more plausible alternative explanation that the heat from the cells did not arise at all from nuclear fusion.

The earliest that Pons and Fleischmann could envision giving a paper was at an American Chemical Society (ACS) meeting on the second week in April. However, by then Jones’ abstract would have already been published, so that seemed to be out of the question. To protect their patent rights, the Utah group felt that their only option was to hold their own press conference to announce their discovery. Of course, this completely violated their agreement with the BYU folks. Officially, the Utah and BYU groups were scheduled to hold a joint press conference on March 24; there they were supposed to announce jointly their findings and FedEx their papers simultaneously.

Before green-lighting the press conference, University of Utah president Chase Peterson phoned Hans Bethe to ask his opinion about the feasibility of initiating nuclear fusion in electro-chemical processes. Hans Bethe was a great choice: he was an eminent physicist and Nobel Laureate; furthermore, he had co-authored the first major paper on nuclear physics. When Peterson informed Bethe that Pons and Fleischmann claimed to have observed room-temperature nuclear fusion in their electrolytic cell, Bethe responded that this sounded extremely unlikely. Peterson then told Bethe that BYU scientists were also claiming the observation of cold fusion and the Utah group did not want to be scooped. Bethe gave the prescient response, “Let BYU publish alone; let them make fools of themselves.” Needless to say, the Utah group did not heed Bethe’s advice.

On the morning of March 22, 1989, the news director at the University of Utah alerted the press that they would hold a press conference the following day to announce that Pons and Fleischmann had sustained a nuclear fusion reaction in an electrolytic cell for one hundred days. Immediately, two papers, the London Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal, did some research and fired off articles on March 23. Stan Pons, Martin Fleischmann and various University of Utah administrators held a press conference on Thursday March 23, 1989 to announce that they had seen nuclear fusion at room temperature in an electrochemical cell. They ‘confirmed’ their claim that they had observed at least one cell produce a large amount of ‘excess heat’ for one hundred days. The magnitude of the excess heat was so large that it could only be a result of nuclear fusion. Furthermore, this amount of heat made it feasible to utilize cold fusion for commercial energy production. At the press conference, the chemists would indulge in some bashing of ongoing efforts to produce energy by nuclear fusion. They noted that physicists had been trying for 50 years to produce nuclear fusion that would ‘break even,’ i.e. produce more energy from fusion than was input to the system. Despite spending billions of dollars on gigantic fusion reactor projects, these still seemed decades away from success. The announcement by Pons and Fleischmann, if correct, would be one of the great scientific discoveries of modern times; and it would immediately produce a revolution in clean energy production. No wonder the controversy over cold fusion claims made front-page headlines all over the world.

As we will see, in addition to debates over the science, there were also plenty of political and psychological undercurrents that contributed to the coming disputes over whether cold nuclear fusion had been observed in electrolytic cells. Here are some of the issues that came into play in the ensuing drama. We will expand on these issues as they arose during the cold fusion craze.

- Fame & fortune – when they believed that were seeing room-temperature nuclear fusion, Pons and Fleischmann had dreams of a Nobel Prize, plus great wealth from patents on their process. This clouded their thinking, led them to announce their ‘discovery’ before they had thoroughly researched it, and eventually led them to make false and/or contradictory statements about their accomplishments.

- Paranoia – the researchers at the University of Utah worried that others (scientists, national laboratories, and elite universities) could steal the credit, and potentially patent rights and fame, from the ‘provincial’ scientists in the Rocky Mountain area. This made Pons and Fleischmann reluctant to share credit with others, to collaborate with them, and even to explain the details of their research apparatus to potential competitors.

- Friction between scientific disciplines — chemists were jealous of the enormous research grants that physicists receive from the federal government. While physicists were getting billions in federal grants for ‘hot’ fusion that still seemed decades away, chemists had apparently produced workable fusion from a ‘high school-level’ electrochemistry experiment. Chemists pounded away at this issue, expressing their glee that chemists were able to solve this most important energy problem with no substantial research funding.

- Utah vs coastal elites – both Utah and BYU were delighted at the prospect that they might generate enormous amounts of money from patents connected with the cold fusion process. This would put the state of Utah squarely on the map of elite research centers; and it would enable them to receive their share of wealth and fame. This is one of the reasons that the state of Utah immediately rushed to provide Pons and Fleischmann with millions in state aid. It also explains why they were so insistent that a new research institute would be centered in Utah.

- Competition among newspapers: the Wall Street Journal appears to have been irked that the New York Times and Washington Post gained much publicity from the publication of path-breaking scientific achievements; it appeared to WSJ staff that NYT and WAPO always seemed to land the first story about breakthrough achievements in science and technology. It seems that the Wall Street Journal was determined to gain the lead and publish the first and most complete articles on cold fusion. After the initial press conference, the initial WSJ front-page headline stated, in block capitals, “TAMING H-BOMBS? TWO SCIENTISTS CLAIM BREAKTHROUGH IN QUEST FOR FUSION ENERGY. IF VERIFIED, UTAH EXPERIMENT PROMISES TO POINT THE WAY TO A VAST SOURCE OF POWER.” As the cold fusion saga unfolded, the WSJ was frequently in the lead when reporting ‘confirmations’ of cold fusion by other groups; and when others failed to reproduce the Pons and Fleischmann results, the WSJ sometimes played down the negative reports.

- The philosophy of scientific research. Many journalists contrasted the “optimism” of Pons and Fleischmann with the “pessimism” of more cautious scientists who had not dared to look for nuclear fusion in an unlikely place. And some scientists claimed that in order to observe a new phenomenon, one had to ‘believe’ that the phenomenon was genuine. This completely contradicts the notion that scientists should be skeptical of all claims, and in particular to subject their own theories to intense skepticism. As we have in a couple of our previous posts, we again quote Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman here: “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool” (more quotes from Feynman later).

The March 23 press conference by Pons and Fleischmann generated an enormous amount of press. The Wall Street Journal announced it in banner headlines on their front page. Through the next several months, the WSJ would continue to trumpet positive claims about cold fusion, while downplaying the steadily rising chorus of skeptics. Although the WSJ seemed determined to lead the way in covering the cold fusion bandwagon, the Pons and Fleischmann claims were also highlighted by cover stories in major journals. For example, the cold fusion claims appeared as cover stories in Time, Newsweek and Business Week, as shown in Fig. III.4.

Figure III.4: The covers of Time, Newsweek and Business Week; the controversy over the cold fusion claims of Pons and Fleischmann was front-page news around the world.

Since the electrolytic cells of Pons and Fleischmann were relatively cheap to assemble and test, dozens of research groups around the world mounted their own cold fusion searches. Immediately following the Salt Lake City press conference, confirmations from other groups around the world were announced. There was a virtual stampede of rushed and sloppy experiments. Groups that understood nuclear physics (and who had good particle and gamma ray detectors) often knew little about electrochemical experiments; conversely, experts in electrochemistry often knew little about nuclear physics. And there was also a strong bias from journalists. Accounts of experiments that claimed positive results were often heralded in front-page newspaper articles, while experiments with negative results were either not reported or were relegated to the back pages.

In retrospect, there were some bizarre features of the Pons-Fleischmann press conference. The Utah group claimed to have seen Deuteron-Deuteron fusion in an electrochemical cell that used deuterated water. The obvious control experiment would be to repeat the electrolytic cell study, but use ordinary water that contained essentially no Deuterium atoms. The cells with ordinary water should show no fusion results. Shockingly, it appeared that Pons and Fleischmann had never run this control! From Eqs. (2), if their experiments were seeing D-D fusion, Pons and Fleischmann should have measured gigantic fluxes of fast neutrons, Helium, Tritium, and gamma rays. Indeed, many nuclear physicists pointed out at the time that if Utah researchers had been present in the room containing their unshielded electrolytic cell, they would have undergone severe radiation damage from the huge flux of neutrons if D-D fusion had been occurring at the claimed rates.

Many of Pons and Fleischmann’s colleagues attempted to repeat those experiments; one of the first questions they asked was whether Pons and Fleischmann had measured fluxes of neutrons and Tritium. Pons and Fleischmann misleadingly answered “Yes” to both those questions. However, their neutron detectors had not measured any appreciable number of neutrons, and in similar fashion the Tritium abundances that they observed were many orders of magnitude smaller than would have been required to produce the excess heat they claimed. Pons and Fleischmann were certainly seeing very small numbers of neutrons and Tritium. Another disturbing aspect of the Pons and Fleischmann press conference is that they were asked if anyone else was doing similar experiments. Pons and Fleischmann replied, “We’re not aware of any other experiments.” This was a flat-out lie, as the Utah scientists knew that Steve Jones of BYU was researching essentially the same reaction. The Utah scientists had also lied to the BYU group in promising a joint press conference and simultaneous submission of scientific papers by the Utah and BYU groups.

As we will see, the announcement of a cold fusion discovery inspired a rush to analyze the behavior of electrolytic cells with deuterated water. This led to a number of slipshod ‘confirmation’ announcements, as groups tried to jump on the cold fusion bandwagon. Many researchers were under the impression that it was relatively easy to measure heat, and also to identify particles (e.g., neutrons, Tritium, Helium) and gamma rays. This is quite incorrect. In the case of heat, the electrolytic cells would operate normally for long periods of time; then the system might heat up for other periods. A precise measurement of ‘excess heat’ requires very careful calorimetry, which Fleischmann and Pons and many other researchers failed to do. For example, Pons and Fleischmann used “open” electrolytic cells, where the D2 and O2 gases produced are allowed to escape from the cell. This makes the calculations of calorimetry very difficult. As for particle detection, it is relatively easy to identify massive numbers of neutrons or Tritium. However, if the number of particles is small, near the limits of detection, it is essential that the system be shielded to protect from cosmic rays, which contain neutrons. In the case of Tritium, it is critical to avoid contamination from other sources of Tritium. And measurement of gamma rays requires that researchers have sensitive detectors and know how to calibrate their instruments. Many “confirmations” of cold fusion resulted from failure to make precise measurements of these quantities.

The First Cold Fusion Paper:

On April 10, the Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry and Interfacial Electrochemistry published the first paper, Electrochemically Induced Nuclear Fusion of Deuterium, by Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons. The paper was supposed to mute some of the criticism that arose because Pons and Fleischmann had not previously published, or even submitted, a research paper when they held a press conference on March 23 to claim that they had observed room-temperature nuclear fusion in an electrolytic cell. Publication of this paper did mollify some of the criticism that had appeared in various papers. For example, the Wall Street Journal published a banner headline regarding the publication, HEAT SOURCE IN FUSION REACTION MAY BE MYSTERY REACTION – FUSION PAPER SHEDS LIGHT ON FIND, EASING SOME SCIENTISTS’ SKEPTICISM. However, the paper seemed to raise as many questions as it answered.

First, the paper made no mention of control experiments, where the cells would be run with normal water instead of heavy water. This seemed such a glaring oversight that many scientists were surprised that the paper survived peer review. As it happens, the paper was not peer-reviewed; the managing editor of the journal Roger Parsons, a good friend of Martin Fleischmann, served as the sole referee. The paper also reported seeing neutrons and Tritium, which would be expected from the D-D fusion equations of Eq. (2). However, the reported amounts of neutrons and Tritium were many orders of magnitude smaller than the excess heat claimed by Fleischmann and Pons. This accounts for the reference to “Mystery reactions” in the Wall Street Journal article. The paper also included no raw data – readers had to assume that the data had been analyzed correctly.

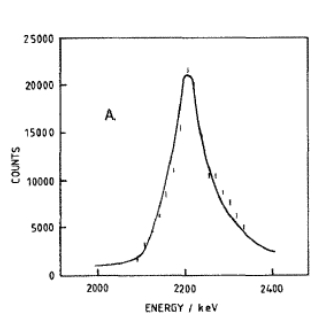

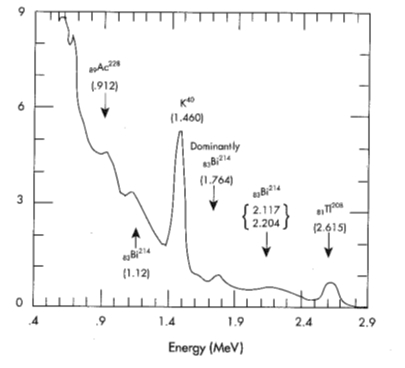

One final issue was the gamma ray spectrum published by Fleischmann and Pons. They claimed to have measured gamma rays that emerged when their cells were producing excess heat. Figure III.5 shows the gamma ray spectrum, a single peak at 2.2 MeV, the energy of the gamma ray that should emerge when fast neutrons from D-D fusion combined with protons via the mechanism of Eq. (3). This is Figure 1A from the Fleischmann-Pons paper. The problem was that scientists who were familiar with gamma ray spectra from nuclear reactions immediately said, “That graph is wrong.”

Figure III.5: The gamma ray spectrum from the electrolytic cells that was claimed by Fleischmann and Pons; it is Fig. 1A of their first paper. Scientists who were familiar with gamma ray measurements stated that this curve looked nothing like a typical gamma ray spectrum.

The graph of Fig. III.5 had a shape that was quite different from a gamma ray spectrum from this reaction. The graph above was ‘clipped:’ it showed only the gamma rays immediately surrounding the 2.2 MeV (or, equivalently, 2200 keV, kilo electron-Volts). Fleischmann and Pons showed only a single peak and not a full gamma ray spectrum that would include energy regions above and below 2.2 MeV. A full spectrum would include gamma ray peaks from other reactions, which would allow scientists to determine whether the peak was actually at 2.2 MeV or was in another location. In addition, when gamma rays pass through detectors, they produce characteristic features (e.g., ‘single and double escape peaks’ and ‘Compton edges’) that are lacking in Fig. III.5. When their gamma ray peak was criticized, Fleischmann and Pons produced an Erratum that included a wider range of energies. But even this new figure was objectionable.

Richard Petrasso and colleagues at MIT wrote a paper that was published in Nature on May 18, 1989. After obtaining the full gamma ray spectrum measured at Utah, the MIT group pointed out three issues with the Fleischmann-Pons figures. First, the linewidth of their peak was a factor of 2 smaller than allowed by their detector; second, a Compton edge that should appear at 1.99 MeV was absent; and their estimated neutron production rate was too large by a factor of 50. Petrasso et al. asserted that their only explanation for this peak was that it was an ‘instrumental artifact.’ Figure III.6 shows the full gamma ray spectrum that Petrasso et al. obtained from the Pons and Fleischmann press conference. This figure shows spectral lines from several elements that are commonly found in substances such as glass beakers and concrete. However, there is no sign of a peak at 2.22 MeV. It has been claimed that the mislabeling of this spectral line constituted fraud by Fleischmann and Pons. Our view is that the treatment of the gamma ray spectrum by Fleischmann and Pons represents a mixture of dishonesty fueled by dreams of a Nobel Prize and glaring incompetence (later, the Utah scientists claimed that they saw a spectral line at 2.45 MeV, and not 2.22 MeV). The changing story about their gamma rays certainly constitutes scientific misconduct on the part of Fleischmann and Pons.

Figure III.6: The gamma ray spectrum that Petrasso et al. extracted from the Pons-Fleischmann press conference. The spectrum shows gamma ray lines from various elements, but nothing at 2.22 MeV.

The question of fraud vs. incompetence is highly subjective. In this instance we lean towards incompetence primarily because we consider it the more important overall issue with Pons and Fleischmann. Here, it is interesting to review the comments of Robert Park, a physics professor at the University of Maryland, who was the head of the Washington, DC office of the American Physical Society. He published a weekly online newsletter on scientific issues. After the first cold fusion press conference, Park was asked off the record by Robert Bazell, the science editor for NBC News, if the Pons and Fleischmann claims constituted fraud. “No,” said Park, “but give it two months and it will be.” In retrospect, Parks’ comments on the cold fusion scandal were remarkably prescient.

IV: The ”Cold Fusion Wars:”

Over the next weeks in 1989, while “cold fusion” remained a hot topic (so to speak), groups from around the world reported ‘confirmation’ of the claims of Pons and Fleischmann. But fairly rapidly, the subject became a point of contention between scientists (mostly physicists) who debunked the electrochemical reactions, and another group of researchers (mostly chemists) who seemed to accept uncritically the cold fusion claims. In particular, physicists claimed that the Pons-Fleischmann experiments should have produced massive amounts of neutrons and tritium. In fact, physicists were fond of the dark-humor joke “Why are the claims of cold fusion wrong? Because Pons and Fleischmann are still alive.” The flux of neutrons that should have accompanied the Watts of heat released from electrolytic cells would have constituted a fatal dose of neutrons to the experimenters. When nuclear physicists run experiments that produce large numbers of neutrons, they surround the detectors with thick concrete shielding. This prevents the fast neutrons from penetrating outside the detector area, where those neutrons would injure or kill the experimenters.

On April 12, 1989, the American Chemical Society meeting in Dallas scheduled a special session on cold fusion. This was later referred to as the “Woodstock” of cold fusion, and could well have marked the high point of the cold fusion saga. Pons and Fleischmann gave the opening talk at this meeting. The attendance was so large that the session was moved to the Dallas Convention Center theater, where they drew an audience estimated at 7,000 people or more. The atmosphere was festive, and the spirit among chemists was celebratory. It appeared that two chemists with an electrolytic cell setup that could have been duplicated in high school chemistry classes had apparently succeeded where physicists had failed. In opening this special session, ACS president Clayton Callis remarked that “Much has been learned about plasma physics. While much progress has been made, the goal has remained elusive and the large, complicated machines that are involved appear to be too expensive and too inefficient to lead to practical power. However, chemists may have come to the rescue.” Callis’ remarks were followed by a burst of laughter and applause from the chemists in the audience.

The chemists were only too happy to stick it to the physics community; this exposed some of the resentment that chemists felt over the gigantic sums that the U.S. and world governments had spent on enormous physics projects. Pons and Fleischmann were viewed as heroic research pioneers, lauded for searching for nuclear fusion where no one had previously thought to look. It was soon enough after the March 23 press conference that reports of negative searches were just coming in; although a number of ‘confirmations’ had been announced, these resulted from experimental searches that would eventually be retracted or discredited.

The Boys from Caltech:

On May 1, the American Physical Society meeting in Baltimore held a special session on cold fusion. Pons and Fleischmann had been invited to give a presentation but they did not show up (by this time, Pons and Fleischmann were giving very few public lectures, claiming that they were too busy with their measurements. However, they were not too busy to travel to Congress to lobby for research support for cold fusion). Steve Jones did give a presentation on his own results, where he highlighted the difference between his neutron measurements and the neutron abundances that could be inferred from the Utah experiments. Jones said, “The ratio of our [neutron] results to the Pons-Fleischmann results is about the same ratio between the dollar bill and the national debt.” The Pons and Fleischmann press conference had inspired many scientists either to verify the stunning claims of the Utah chemists, or to debunk them. A notable group that worked to debunk the cold fusion claims was a trio of scientists from Caltech.

Figure IV.1: Scientists from Caltech who presented strong criticism of cold fusion claims at an American Physical Society session on cold fusion in May 1989. From L: Nathan Lewis; Steve Koonin; Charles Barnes.

Steve Koonin was a theoretical nuclear physicist who had established a reputation as a sharp and knowledgeable scientist. Koonin had written a book on computational methods in physics, and he was also the head of the JASON group of scientists that advised the U.S. government on scientific and technical matters, mainly those dealing with national defense. Nate Lewis was an experimental chemist at Caltech who studied electron transfer reactions and their effects in photosynthesis and semiconductors. When they heard the fantastic claims from the University of Utah electrochemists, Koonin worked on theoretical aspects of fusion in materials, and Lewis carried out experiments to search for signs of fusion in electrochemical cells. Caltech physicist Charles Barnes provided some of the world’s best neutron detectors that were used in Lewis’ experiments.

Koonin first calculated the probability that fusion could occur at room temperature from free Deuterium atoms. This would avoid having to account for the mechanism by which Deuterium was captured in Palladium electrodes. It was well known that Palladium could accommodate very large amounts of Hydrogen or Deuterium. The question was whether the density of Deuterium in the Palladium lattice was sufficiently high that Deuterons could fuse sufficiently often to release Watts of energy. For Deuterium atoms in deuterated water, the probability of two Deuterium nuclei fusing was one fusion every 1064 seconds (our universe is only about 4 x 1017 seconds old). To calibrate this rate, if the Sun was composed entirely of Deuterium at room temperature, it would produce one spontaneous fusion per year. Each electrolytic cell used by Pons-Fleischmann contained about 1022 atoms of Deuterium, so spontaneous fusion of free Deuterium in their cells would occur once every 1042 seconds. To produce one Watt of fusion power from fusion of free Deuterium nuclei in the Pons-Fleischmann experiment (roughly what the Utah group was claiming to observe) would require an increase by 54 orders of magnitude over the rate for free Deuterium! There was no conceivable physics process that would account for this increase in rate. Note that the ratio of the diameter of the visible universe to the diameter of a single proton is 1041.

In order for two Deuterium nuclei in deuterated water to fuse, you need to decrease the distance between them by at least a factor of 10,000 from their normal distance in the D2 molecule. There was no known physical mechanism for Deuterium nuclei in an electrolytic solution to reach the densities needed to produce the number of fusion reactions necessary for the heat estimated by Pons and Fleischmann. Although metals such as Pd can pack in extremely large amounts of Deuterium in the spaces in the Palladium lattice, the densities and pressures reached are nowhere near what is needed for fusion to occur. In fact, quite a lot was known about the absorption of Deuterium into Palladium rods. Pons and Fleischmann felt that, because Palladium could absorb very large amounts of Deuterium, the Deuterium might be packed so close together in a Palladium rod that nuclear fusion would occur. However, Koonin pointed out that Deuterium atoms in a Palladium rod would actually be farther apart than the Deuterium atoms in a molecule of D2O!

To obtain the enormous amount of fusion in the electrolytic cells would require a totally new mechanism, and one that does not satisfy the nuclear physics involved in fusion, since Pons and Fleischmann were not observing neutrons or Tritium in the levels needed to accompany this much heat. After Koonin presented his theoretical calculations at the May 1 APS meeting, he finished with “My conclusion, based on my experience, my knowledge of nuclear physics, and my intuition, is that the experiments are just wrong. And that we’re suffering from the incompetence and perhaps delusion of Drs. Pons and Fleischmann.” Caltech chemist Nate Lewis presented the results of his experiments with electrolytic cells with a Palladium electrode. His first bombshell was the revelation that Pons and Fleischmann had not carefully measured the amount of heat supplied to the cells and released by them. Rather, they had used an estimate of the heat generated by the cells. Another surprise was that Pons and Fleischmann had not carried out the most elementary control experiment. This would be to repeat their electrolytic experiments, but replacing the deuterated water in their cells with ordinary water. Since Pons and Fleischmann were claiming that the excess heat in their cells was due to D-D fusion, once they eliminated the Deuterium they should see no excess heat. Lewis had carried out extensive measurements of calorimetry, and his result was that no excess heat was being produced in these cells. In fact, the measured output power of Pons and Fleischmann’s cells was always less than the input power. As Lewis put it, “The cells were not good fusion heaters, they were great fusion refrigerators.” Furthermore, Lewis had carried out very sensitive attempts to detect telltale signs of fusion. He summarized his results at the Baltimore meeting: no neutrons, no Tritium, no Helium, no gamma rays coming from nuclear reactions in the cells. After Lewis’ presentation, he received a sustained standing ovation from the audience at this cold fusion session. Many physicists were dubious about cold fusion from the start, but from this point on nearly all physicists regarded cold fusion as thoroughly debunked.

However, Pons and Fleischmann claimed to be happy with the results announced at the Baltimore meeting. “We are extremely pleased because they confirm our findings,” Pons told a journalist. “The absence of neutrons doesn’t concern us in the slightest.” Pons meant that he and Fleischmann had concocted a theory of fusion in the presence of Palladium. They felt that the fusion reaction proceeded only by Eq. (2c), that is, only by producing Helium-4 and a gamma ray of energy 23.8 MeV. We will return later to this conjecture, which is completely at odds with well-known nuclear physics.

An interesting feature of the cold fusion debates was the way that journalists framed the debates between the proponents of cold fusion and the skeptics who were trying to debunk those claims. In many cases, those claiming to have observed cold fusion were portrayed as brave, optimistic scientific pioneers who had the foresight to search for new science in unlikely places. Those pioneers were being attacked by small-minded critics whose own areas of research and government funding were threatened by these revolutionary new results. For example, in an editorial on April 12, 1989 the Wall Street Journal stated “The world does not yet know conclusively whether Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann will enter science’s pantheon with Ernest Rutherford, one of the giants of 20th century physics. The world, however, is getting a rare look at the clash between science and the politics of science – a clash between human curiosity’s innate optimism, and the compulsive naysaying of the current national mood.” In another editorial, the WSJ opined that we were witnessing a clash between “the creative impulse of a Fleischmann and Pons” contending with “what might be called the ‘Academic Mentality.’” Another term for the “academic mentality” might be the “scientific method.”

Other journalists described the conflicts between the electrochemists and their antagonists as a clash between good vs. evil, or progress vs. stagnation; they claimed that a major factor motivating the critics of cold fusion was jealousy. Dana Rohrabacher, a Republican congressman from California, described those who attacked the cold-fusion advocates as “small, petty people without vision or curiosity.” Stan Pons chimed in with “Chemists are supposed to discover new chemicals. The physicists don’t like it when they discover new physicals.” Newsweek contrasted the two groups of scientists: physicists were the “self-anointed high priests of science.” Newsweek also claimed that physicists regarded chemists as “mere beaker keepers more suited to plumbing the wonders of polyester than the mysteries of the universe.”

In fact, the journalists had it exactly backwards. Those who advocated for cold fusion had fooled themselves into believing that they were seeing nuclear fusion at room temperatures. These true believers were not rigorously testing their own theories and trying to poke holes in them. In fact, once Pons and Fleischmann convinced themselves that they were seeing cold fusion, they brushed aside all criticism of their theory; they even resorted to claiming the observation of phenomena that they hadn’t seen. Richard Feynman, one of the greatest scientists of the 20th century, described how scientists should treat claims skeptically; and in particular how scientists should be skeptical of their own hypotheses. “It’s a kind of scientific integrity, a principle of scientific thought that corresponds to a kind of utter honesty—a kind of leaning over backwards. For example, if you’re doing an experiment, you should report everything that you think might make it invalid—not only what you think is right about it; other causes that could possibly explain your results; and things you thought of that you’ve eliminated by some other experiment, and how they worked—to make sure the other fellow can tell they have been eliminated.”

Feynman continued “Details that could throw doubt on your interpretation must be given, if you know them. You must do the best you can—if you know anything at all wrong, or possibly wrong—to explain it. If you make a theory, for example, and advertise it, or put it out, then you must also put down all the facts that disagree with it, as well as those that agree with it … The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool. So you have to be very careful about that. After you’ve not fooled yourself, it’s easy not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest in a conventional way after that.”

Two True Believers:

Another special session on cold fusion took place at a meeting of the Electrochemical Society in Los Angeles on May 8. In planning this session, initially the organizers claimed that they would only allow papers that confirmed the Pons-Fleischmann results, not those that refuted them! This attitude completely contradicted the principle that scientists should be strong skeptics of claims until they are presented with overwhelming evidence. Eventually the organizers of this conference backed down and allowed both positive and negative papers about cold fusion. Once again, Nate Lewis of Caltech presented his thorough and extremely negative research on cold fusion in electrolytic cells. And Pons and Fleischmann had changed their story about their research. This time, instead of claiming to have observed neutrons and Tritium from D-D fusion, they claimed that the only process occurring in their cells was D-D fusion leading to Helium-4 plus a gamma ray. The claim was that the energy from the gamma ray heated up only the electrodes and the electrolyte. This would ‘explain’ why no neutrons or Tritium or high energy gamma rays were observed; however, there was no explanation for the lack of fast neutrons and Tritium. Furthermore, the energy of the gamma ray, 23.8 MeV, was sufficiently high that it should shoot out of the liquid without losing much of its energy. There was no feasible physical process that could explain how a gamma ray of such high energy could transfer all of its energy to the electrolytic cell. Furthermore, if fusion was occurring through that pathway, the cells should have been producing 100 million Helium-4 nuclei per cubic centimeter in the lattice. Experimenters at the meeting stated that their helium detectors had turned up less than 10 Helium-4 per cubic centimeter. So, at the Los Angeles ECS meeting several researchers debunked the Pons-Fleischmann claims.

During the question period at the Los Angeles ECS conference, Pons and Fleischmann put on an incredible act. Pons was asked if he could explain why the 2.2 MeV gamma ray peak they published was so narrow; he answered simply “No.” But Fleischmann then chimed in, “I’m well aware the peak is wrong. I’ve discussed it with Stan. It perturbs me. That was not meaningful using the equipment we had at the time.” After initial criticism that the pair had not run controls with light water rather than deuterated water, Pons had claimed that they had observed excess heat with light water cells as well. This would have been an astonishing claim, since validation that they were observing D-D nuclear fusion would have required no excess heat when running the cells with light water. When asked about Pons’ claim, Fleischmann responded “That’s absolute nonsense, complete nonsense.” Finally, Pons was asked about his announcement at the March 23 press conference that the group had observed large amounts of Helium-4. “I didn’t make that statement,” Pons asserted, despite the fact that he had made such a claim in the presence of several journalists who had witnessed the March 23 press conference.

Many scientists attending this conference felt that the cold fusion claims of Fleischmann and Pons had been demolished by the negative results from careful experiments. However, at the Los Angeles meeting two supposedly distinguished scientists reported agreement with the University of Utah results.

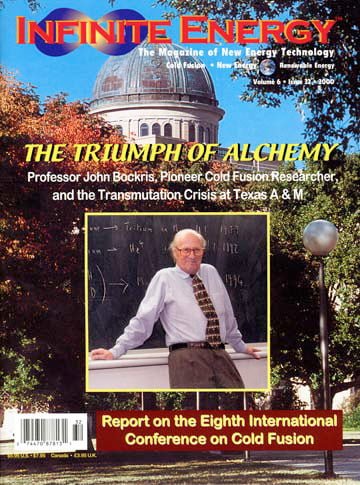

John Bockris was a distinguished professor of chemistry at Texas A&M University. He had published over 600 papers and had written over a dozen textbooks. However, some of his colleagues volunteered that quite a few of his papers seemed to be completely wrong. First, Bockris criticized Nate Lewis’ negative results. “I think it’s important to note the hints constantly made by Dr. Lewis that there’s something faulty about all this heat. It is really he who is the only one who says this.” Bockris continued that “fourteen labs, from six different countries, had measured both heat and nuclear by-products.” He concluded “There’s no use going on denying it with the rest of the world confirming it.”

Figure IV.2: John Bockris, distinguished professor of chemistry at Texas A&M University, appearing on the cover of Infinite Energy magazine, a journal that enthusiastically supported cold fusion claims. Bockris claimed to have confirmed several aspects of cold fusion, most notably large amounts of Tritium in electrolytic cells.

Bockris claimed to have seen both heat and nuclear by-products in his electrolytic experiments. But his most (in)famous claim was to have detected massive amounts of Tritium in a few of his cells. In this, he was almost alone in claiming an abundance of Tritium and was contradicting Pons and Fleischmann’s “theory” that the fusion only occurred via reaction 2(c). Other laboratories, in particular Los Alamos and the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) in Mumbai, India had reported detecting Tritium; however, both labs had large amounts of Tritium on site, and could not overcome the difficulties of isolating their cells from Tritium on the premises. Bockris also had peculiar ideas about how to react to mind-blowing claims. Bockris’ own philosophy of science was completely opposite to the maxim “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof.” He stated “I am not a person who believes that at the beginning of a new discovery, you should look too hard at it … The world is being born anew in this last year, and fantastic ideas are being discussed and being created, and right now it’s not good to ask too many questions.” These notions also contradict Richard Feynman’s advice that scientists should be extremely skeptical of both their own work and results claimed by others. A few months later, Bockris doubled down on his Polyanna beliefs to a DOE committee that visited his lab to analyze his claims. He stated that “When persons tell us that they have carried out the electrolysis of Deuterium evolution in Palladium and see nothing new, particularly if (as is usual) they are furious about it, have spent little time on it, and have little experience as to how to do experiments of the type named, we tend to discount their contribution.”

Martin Fleischmann also echoed Bockris’ arguments about belief in one’s work. In June 1989, Fleischmann visited Harwell Laboratories in Britain. A group at Harwell had made extensive measurements of the Pons-Fleischmann cells, and they had also analyzed cells from the Bockris group. They found no excess heat, no fast neutrons, no Tritium, no Helium and no gamma rays. Colleagues of Fleischmann who saw him at a subsequent conference in Stockholm report that he said “The Harwell people never believed in it, and that if you really don’t believe something deeply enough before you do an experiment, you will never get it to work.”

Bockris and his colleagues at Texas A&M claimed that some of their cells had registered 10 million Tritium atoms per milliliter of solution. These numbers were so much higher than were measured anywhere else in the world that many scientists suspected that someone was “spiking” the cells with tritiated water. One disturbing fact was that cells with massive amounts of Tritium nearly always appeared just before the group’s funding agency, the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), was due to visit the lab. But a more conclusive result came from measurements of cells that registered massive amounts of Tritium. The Bockris cells had 98% deuterated water and only 2% normal H2O. However, cells with high T had much higher levels of ordinary hydrogen. Since tritiated water is normal H2O with Tritium added, if the cells were being spiked with Tritium they would end up with higher amounts of normal water than the other cells; and this is what was observed. However, John Bockris never wavered in his belief in cold fusion, and he certainly had no doubts about the results he claimed, even though no other group ever measured Tritium abundances that were anywhere near what Bockris claimed.

Robert Huggins was a distinguished professor of materials science at Stanford University. He had been a pioneer in the field of solid state ionics. Over the years he had been funded lavishly by federal agencies, but in recent years his funding had decreased. When Huggins first heard about the Pons-Fleischmann claims of cold fusion, he set up his own electrolytic cells. Huggins set up control cells to test the theory of cold fusion. Some of his cells contained deuterated water, while the control cells had normal water. When Huggins ran the cells under otherwise identical conditions, the deuterated cells ran hotter. The difference in temperature was small, only about 1 degree Celsius, but Huggins asserted that the only explanation for the difference was cold fusion. Huggins claimed “Because heavy water, containing deuterium, a heavy form of hydrogen, and regular water, containing simple hydrogen, are almost chemically identical, they would produce identical results if the effect were caused by a chemical reaction … The results in the heavy water seem to be larger than any chemical reactions we know about can justify.”

Figure IV.3: Robert Huggins, distinguished professor of material science at Stanford. Huggins studied electrolytic cells and claimed to see a small amount of excess heat from cells with deuterated water, as opposed to cells with normal water.

Huggins didn’t realize that heavy water and ordinary water can have significant differences, particularly in the presence of Lithium. The electrical conductivity of heavy water with Lithium is significantly smaller than the conductivity of ordinary water with Lithium. This means that when hooked up to a battery, the heavy water cell will run hotter than one with normal water. This property had been known since 1958. As might be suspected, Pons and Fleischmann saw the Huggins results as clear confirmation of their work. At a Workshop on Cold Fusion phenomena in Santa Fe on May 23, 1989, Huggins repeated his claims. He then stated that his cells were observing cold fusion because of the unique way he had prepared his Palladium electrodes. Several researchers, particularly from Los Alamos and Caltech, asked if Huggins could loan them some of his Palladium electrodes (Huggins claimed that 100% of his cells produced excess heat with deuterated water). The Caltech researchers offered to run Huggins cells with their sophisticated particle detectors, and Nate Lewis at Caltech offered to autopsy one of Huggins’ Palladium disks to test for Tritium or Helium. Huggins claimed that he would need research funding to purchase and process Palladium; but when Los Alamos offered to give him the Palladium, he stated that he was too busy on his own research and might get back to them later.

DOE Committee Investigates Cold Fusion:

In late April 1989, the US Department of Energy (DOE) formed a blue-ribbon committee to investigate claims of cold fusion. The committee was chaired by John Huizenga, a professor of chemistry and physics at the University of Rochester. Huizenga’s committee included several distinguished researchers from physics, materials science and electrochemistry. One of the committee members was Clayton Callis, the president of the American Chemical Society. The committee was charged with three objectives: to give a thorough review of the theory and experiments regarding cold fusion; to identify key experiments that might test cold fusion; and to recommend the role that the DOE should take regarding cold fusion.

Huizenga tried to visit every laboratory that had reported positive results for cold fusion. Here he ran into a problem, as Stan Pons refused to allow a visit on the grounds that the DOE committee was packed with non-believers. Pons said that he would allow the DOE committee to visit his lab only if the committee added scientists who had reported positive results (the DOE refused); he even threatened to bring an injunction against the Huizenga panel. Finally, the DOE committee agreed to a compromise with Pons: a committee would visit the lab at the University of Utah, but committee members Mark Wrighton of MIT, Steve Koonin of Caltech, and Will Happer of Princeton would not attend; and electrochemists Larry Faulkner of Illinois and Harry Miller of AT&T would be added to the visiting group.

Electrochemist and DOE committee member Al Bard told Pons that the committee wanted to see all the raw data on a single operating cell; in particular, the committee wanted to see a calibration curve, which would show the “baseline” against which the excess heat could be extracted. Pons expressed his eagerness to show the committee his lab. “I have a cell ready; it’s getting excess heat right now; it’s putting out like mad.” But when the panel members arrived, Pons claimed that a power outage had occurred, so that no cells were operating. Even more concerning, Pons had no calibration curve for the committee. He explained that he might have had a calibration curve at home; the panel members were stunned that Pons failed to produce this curve that they had specifically requested.

The DOE committee then visited Texas A&M, which was a hotbed of cold fusion “confirmations.” Chemist John Appleby showed the committee his cells that he claimed were producing excess heat. Appleby showed the committee the raw data from a strip chart that supposedly measured excess heat. The committee noted that the “excess heat” event was a tiny blip on the chart; in fact, the height of the blip was smaller than the width of the line on the chart. Asked how Appleby extracted the excess heat claim from a squiggly line on a strip chart, Appleby replied “We had graduate students with good eyesight.” But it got worse. The temperature in the cells had remained completely constant, while Appleby saw a tiny decrease in the voltage. Since the voltage went down while the temperature remained constant, Appleby inferred that this showed excess heat due to fusion (!)

The interview with John Bockris went even worse, if that was possible. Panel members asked Bockris why his graphs showed no measurement error bars. Bockris explained “We used to alternate the students, so we got objective measurements of the calibration on the heat cell. If Jack does it like Jill, it is bound to be right.” Committee members found that the wires connecting his cells to instruments used clamps and alligator clips. If they touched a clip connecting to a thermometer, the temperature would shift up or down by a few degrees. This made the measurements essentially useless. Bockris’ lab assistant was asked if the cells ever showed a decrease in heat rather than an increase; the response was that decreases in temperature happened all the time. But Bockris showed no interest in negative results, which “can be obtained without skill and experience.” So, Bockris apparently kept only the results that showed increases in heat, which he ascribed to cold fusion; results that showed decreases in heat were discarded as errors. Huggins came off particularly badly when he was interviewed by the DOE committee. Although he claimed that 100% of his cells produced excess heat with deuterated water, when the committee visited, none of his cells was active (amazingly, this was also the case with Pons at Utah, and Bockris and Appleby at Texas A&M). The DOE committee was unimpressed with the amateurish setup of Huggins’ experiments, and also with his failure to account for measurement errors. Committee members noted that the “excess heat” measured by Huggins tended to occur on weekends. When industries close down on weekends, the line voltage will often increase, and Huggins had not accounted for that. When Huggins was informed that the higher temperatures from his cells with deuterated water likely resulted from the fact that D2O has a significantly smaller conductivity than H2O (particularly in the presence of Lithium), Huggins responded that this effect was “Small potatoes,” even when it was pointed out that the difference in conductivity could account for 100% of the effects he observed. The committee’s conclusion was that Huggins’ experiments were riddled with large uncertainties.