February 16, 2024

Update May 14, 2024:

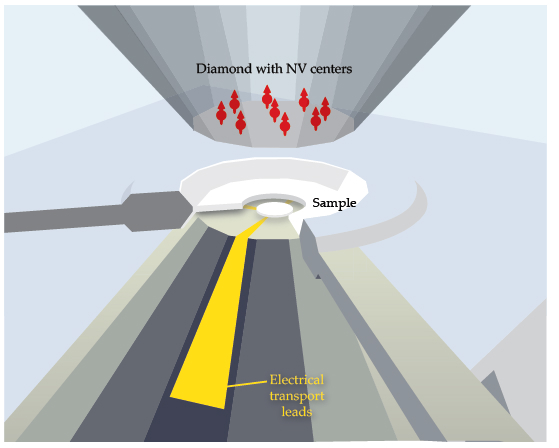

When we uploaded our initial story regarding University of Rochester physicist Ranga Dias, his situation was highly uncertain. Here we briefly recap the story of Ranga Dias and his research. Dias and his collaborators, a group at Rochester and a second group at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas led by Ashkan Salamat, had published two papers in Nature claiming to have achieved superconductivity at room temperatures. The first paper, published in October 2020, involved samples of carbonaceous sulfur hydride, or CSH. The authors stated that their samples of CSH became superconducting at a temperature of 287 Kelvin (this is equal to 14° Celsius). The samples were placed in a diamond anvil device shown in Fig. 1 and subjected to very high pressure. The group reported achieving superconductivity at a pressure of 2.67 megabars, equivalent to nearly 40 million pounds per square inch. This claim, if verified, would have produced the first material that went superconducting at room temperature, even if the pressures far exceeded anything found naturally on Earth. However, other research groups failed to replicate the Dias result in CSH. Eventually, under pressure from other scientists, Dias published the raw data from which the results were said to have been obtained.

Figure 1: Schematic picture of a diamond anvil cell. The sample is placed under a diamond, and the diamond then exerts tremendous pressure on the sample.

However, scientists reported that the ‘raw data’ had some strange and disturbing features. Eventually Dias stated that the background signal from his experiment had not been measured, as he had claimed in the Nature article, but had been ‘constructed.’ Other scientists claimed that the background claimed by Dias could be replicated by using a mathematical function. In Sept. 2022, Nature decided to retract that article. This was an unusual step, as none of the authors had agreed that the paper should be retracted. A second follow-up paper on CSH by the group in the journal Chemical Communications was also retracted. However, this time all of the paper’s authors except Dias agreed that the paper should be retracted.

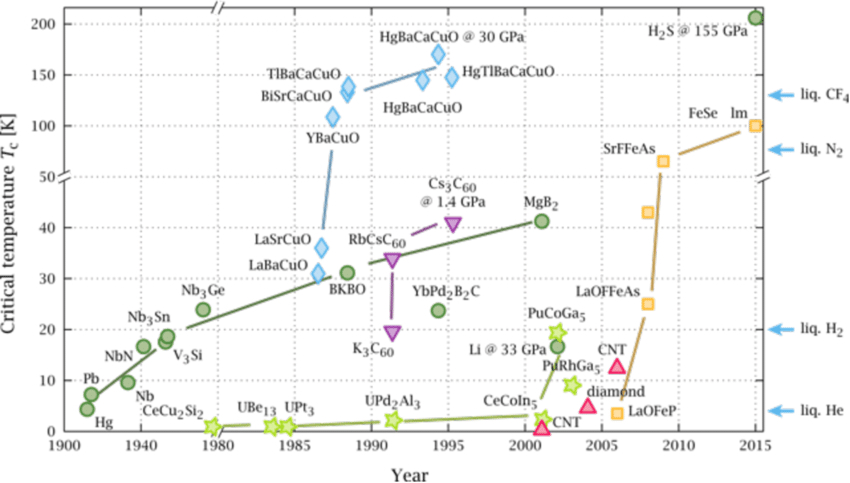

A second paper published in Nature in March 2023 claimed to find superconductivity in a sample of nitrogen-doped Lutetium Hydride (Lu-N-H). Once again, this would have constituted a major breakthrough in superconductivity studies. Figure 2 provides a snapshot of substances that have shown superconductivity. The superconducting temperature Tc is shown here in Kelvin (Celsius = T(K) – 273) vs. the pressure in GigaPascals (1 GPa = 10 kilobars, which is very nearly equal to 10,000 times normal atmospheric pressure). The Lu-N-H sample became superconducting at a temperature of 294 K (21° Celsius) and a pressure of 3 kilobars, one thousand times less pressure than was claimed for the CSH samples. On Fig. 2, note that the two results with the highest claimed superconducting temperatures were both from the Dias-Salamat group. However, because the CSH paper had been retracted, the Lu-N-H claim was subjected to close scrutiny by researchers in this field. After serious questions were raised, Nature retracted the article in Nov. 2023. They stated that eight of the eleven authors of the paper “Expressed the view … that the published paper does not accurately reflect the provenance of the investigated materials, the experimental measurements undertaken and the data protocols applied.” Dias was not one of the authors who agreed to the retraction; however, Ashkan Salamat, the leader of the UNLV collaborators, agreed to the retraction.

Figure 2: Schematic chart of superconducting temperatures, in Kelvin, vs. pressure in GigaPascals or GPa, on a semi-log scale, together with the date of the discovery for each compound. The two highest claimed temperatures were both from the Dias-Salamat group and have both been retracted.

When we uploaded our original post in Feb. 2024, the University of Rochester had mounted an external investigation into possible research misconduct by Ranga Dias. This was interesting because Rochester had already conducted three prior internal investigations into Dias. The first investigation took place when scientists questioned the data handling on Dias’ CSH paper; the second and third investigations took place after papers that he had authored were retracted. University of Rochester spokesperson Sara Miller said that the first two preliminary investigations had “determined that there was no evidence that supported the concerns.” She also stated that Rochester “had considered the matter of the Sept. 2022 retraction of the Nature paper [on superconductivity in CSH] and come to the same conclusion.” These conclusions were puzzling to scientists who had examined the Dias papers and had made serious allegations (described in our post below) regarding the data that was presented. It also seemed strange that Nature had accepted the Dias paper on superconductivity in a Lu-N-H sample, very shortly after they had retracted the earlier superconductivity paper on CSH. So scientists awaited the results of the Rochester external investigation.

In March 2024, a University of Rochester spokesperson confirmed that the external investigators had determined that there were “data reliability concerns” in the papers published (and subsequently retracted) by Dias’ group. Already in August 2023, Rochester had removed Dias from his laboratories and from supervising his students. Journalist Daniel Garisto, who had published two earlier reports on Ranga Dias (see here and here), led a team that published a report in Nature News on March 8, 2024 that discussed Ranga Dias, the Rochester investigation and its conclusions. As part of this report the Nature News team interviewed people who had served on the Rochester external investigation committee, and also talked with graduate students and postdocs from Dias’ laboratory. In addition, they were able to obtain information regarding the two Nature papers that were initially published and subsequently retracted. We will present some of the findings from the Nature News team in this update.

Research Misconduct: Details of the Ranga Dias Story

The work of Ranga Dias and collaborators on high-temperature superconductivity was initially motivated by the results from a German group that found superconductivity in samples of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) at 203 K temperature (-70° C) and very high pressure. Dias hoped that addition of carbon to a hydrogen sulfide system might produce a substance that would be superconducting at even higher temperatures. His students synthesized samples of carbonaceous sulfur hydride (CSH), but they did not conduct experiments to search for the two telltale signs of superconductivity: first, an electrical resistance that rapidly drops to zero; and second the Meissner effect, a zero magnetic field inside the sample.

So Dias’ students were “shocked” when they received a draft manuscript on July 21, 2020. The paper announced the discovery of room-temperature superconductivity in the CSH samples at extremely high pressure. Dias told his students that he had taken all the data on resistance and magnetic susceptibility before he came to Rochester. Another concerning detail was that Dias gave the students almost no time to respond to the paper: they received a draft of the paper at 5:13 pm, and Dias submitted the paper to Nature at 8:26 pm the same evening. The Nature News team managed to obtain the reports of all three referees of the CSH paper. Two of them expressed significant concerns about the dearth of information on the chemical structure of the CSH sample. After three rounds of review, only one referee provided an enthusiastic endorsement of the paper. Nevertheless, Nature published the paper.

The paper elicited great interest in the field of superconductivity; this was not surprising, since a New York Times article on the result was titled “Finally, the First Room-Temperature Superconductor,” even though superconductivity was obtained only at extremely high pressure. However, when other scientists were unable to reproduce the results from the group headed by Dias and Salamat, they pressured the researchers to release their raw data files. After a year the files were released to Jorge Hirsch, a researcher at UC-San Diego. Hirsch found the data suspicious, and he published an assessment of that data on the ArXiv preprint server. Hirsch was concerned with the claimed measurements of magnetic susceptibility. For experiments performed at super-high pressure in diamond anvil cells, it is possible to measure drops in the resistance, but not possible to measure the Meissner effect, expelling of magnetic fields inside the superconductor.

So the Dias group measured instead changes in the magnetic susceptibility. They claimed that rapid drops in the susceptibility showed that the magnetic field was going to zero. However, in order to measure the magnetic susceptibility of the sample, one needs to subtract out very large and fluctuating magnetic fields in the lab. Dias and Salamat claimed that they had measured the magnetic susceptibility of their samples at lower temperatures when the sample was not superconducting. They then subtracted off this susceptibility from their measurements at high pressure. However, Hirsch was suspicious of the raw data that he received. He pointed out that every data point was separated from the subsequent point by exactly 0.16555 nanoVolts. This convinced Hirsch that these ‘raw’ data had either been constructed or otherwise manipulated. Dias and Salamat responded that the suspicious data features were the result of a background subtraction procedure – but this procedure, which they called a “user-defined background,” differed from the statements in their paper. Furthermore, when scientists examined the data files, some concluded that the ‘raw data’ files had apparently been generated by taking the published final data and adding in some background noise. If true, this would be clear evidence of research misconduct. After consulting with various specialists in the field, Nature informed the authors that they planned to retract the paper. This was the first that any of the grad student co-authors had heard of any difficulties with the paper. As a result, even though none of the co-authors informed the journal that they agreed to the retraction, Nature retracted the CSH superconductivity article on Sept. 26, 2022.

In the meantime, Dias had his graduate students and postdocs working on samples of Lutetium Hydride (LuH). One student carried out measurements that showed the resistance dropping to zero at a particular temperature. However, other students worried that the resistance drop might have resulted from a broken probe. They were also concerned because the results were not reproducible for different samples, or sometimes for different measurements of the same sample. So again, the students were surprised when at 2:09 a.m. on April 25, 2022, they received a draft of a paper. Dias stated that he would submit the paper at 10:30 a.m. that same day. The students managed to convince Dias to delay submission by one day. The group held a meeting to discuss their concerns; one concern was that the draft they received had no figures, which made it impossible for Dias’ students to assess the results. Another concern was that the draft contained a description on how to synthesize Lu-H; this was felt to be misleading as the group had not synthesized this compound, but instead had purchased their samples from a commercial firm. Dias agreed to some of the changes sought by members of the group, but he then provided them with an ultimatum: either they acquiesce to the paper as written or remove their names. Several students felt they had no choice but to leave their names on the paper. One of the students later criticized a graph that showed the pressure on the sample, “None of those pressure points correspond to anything that we actually measured.”

At the time the Lu-N-H paper was being considered by Nature, that journal had published a Notice of Concern regarding the CSH paper by that group. Thus, the referees were studying the Lu-N-H paper, knowing that the CSH paper might be retracted. Scientists are of two minds about the decision by Nature to publish the Lu-N-H paper, despite a likely retraction of the earlier paper. Some described this as a “defensible” process, to ignore a previous record when reviewing a paper; whereas others described this as a “naïve” practice. In any case, as a spectacular claim by a group with a dubious record, the Lu-N-H paper was scrutinized very carefully. A group led by Russell Hemley at the University of Illinois – Chicago, conducted experiments on samples he obtained from Dias. He reported finding rapid drops in resistance that he attributed to superconductivity at roughly the same temperature and pressure as the Dias – Salamat group. However, several other research groups found no evidence of superconductivity in the Lu-N-H system.

An important issue for the Lu-N-H research was the measurement of electrical resistance. If the samples became superconducting, the resistance should drop to precisely zero. Other scientific groups were trying to ascertain whether Dias et al. actually measured zero resistance, or whether they simply found a sharp drop in resistance. If the resistance was not actually zero, then the substance may simply have made a transition from an insulating to a conducting state.

Responding to concerns from condensed-matter scientists about the Dias-Salamat Lu-N-H paper, on July 25, 2023 Nature convened a new group of experts to examine the data from that paper. All experts agreed that there were serious unanswered questions regarding the data processing. In the meantime, Dias’ students found significant issues with the Lu-N-H paper. One student stated that the raw data looked nothing like a superconductor; but when the background was subtracted, the compound suddenly looked like a superconductor. Another student complained that the published values for the resistance differed from the raw values that were measured. It appeared that the data had been ‘tweaked’ to make it look less messy. In August 2023, Dias’ grad students, together with Dr. Salamat from UNLV, sent a letter to Nature that outlined what they believed was research misconduct by Dias. This precipitated retraction of the Lu-N-H paper in November 2023.

In retrospect, it appears clear that Ranga Dias committed research misconduct in his work on high-temperature superconductivity. He is no longer teaching classes at Rochester, is unable to work in his laboratory or supervise graduate students. But there are still several unanswered questions regarding this incident. First, what is the culpability of Ashkan Salamat at UNLV? Was he actively involved in mishandling the data, or was he also fooled by Dias? Apparently UNLV is carrying out an investigation of Salamat. In 2020, while work was progressing on superconductivity in the CSH system, Dias and Salamat formed a company, Unearthly Materials, which was designed to use breakthroughs in high-Tc superconductors to manufacture commercial products, and to exploit the applied values of their discoveries. Dias claimed that the group had raised $ 16.5 million in venture capital. Salamat was the CEO of this corporation, but it is understood that he left the company in 2023.

A second question is why Nature accepted the paper on superconductivity in the Lu-N-H system at the same time that they were investigating research misconduct in the earlier research on CSH by the same group. Condensed matter theorist Jorge Hirsch states that Nature should never have even considered publishing the Lu-N-H paper until they had completed their review of issues with the CSH paper. The Sept. 1, 2023 retraction notice states that “Appropriate editorial action will be taken once this matter is resolved.” The chief Nature editor for applied and physical sciences, Karl Ziemelis, stated that he and his colleagues are “assessing concerns” regarding the retracted papers. One does not know if Nature, or other science journals, will change their practices after they review the tortured history of the Dias papers.

One final question is – what was the University of Rochester doing? They claim to have mounted an internal investigation into Ranga Dias after questions were raised about the data handling in his 2020 paper on superconductivity in the CSH system. A second internal investigation was carried out after the CSH paper was retracted by Nature in Sept. 2022. One can imagine that the first investigation might have cleared Dias, at a time when no concrete action had been taken by a research journal. But after his CSH paper was retracted by Nature, it is hard to believe that the research integrity office at Rochester could accept Dias’ claim that the action by Nature was unrelated to any research misconduct, but instead resulted from highly technical concerns about handling of data. Furthermore, it turns out that none of Ranga Dias’ graduate students at Rochester were interviewed for any of the three internal investigations carried out at Rochester! It would seem that the Rochester staff who “investigated” Dias were naïve and easily duped by Dias. After the retraction of the CSH paper by Nature, under the highly unusual circumstance that none of the authors of the paper had agreed to the retraction, it would seem incumbent on the university to mount an external investigation. We hope that the University of Rochester will revamp its research integrity practices, in order to avoid future embarrassment.

Source Material:

Dan Garisto, Superconductivity scandal: the inside story of deception in a rising star’s physics lab, Nature News Mar. 8, 2024 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00716-2

Johanna Miller, An All-in-one Device Creates and Characterizes High-Pressure Superconductors, Physics Today 77, 12 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1063/pt.ivky.chwj

I: Introduction:

In this post, we discuss and review allegations of scientific misconduct regarding physicist Ranga Dias, who is shown in Figure I.1. In this Introduction, we review Prof. Dias’ research prior to his more recent work on high temperature superconductivity. In Section II, we provide a brief review of superconductor physics, and we outline why so much effort is being devoted to finding substances that are superconducting at higher and higher temperatures. In Section III, we review several papers published in recent years by Dias and his collaborators. Several of these papers claimed to make great strides in finding materials with the highest superconducting temperatures. Earlier papers claimed to find high-temperature superconducting materials but required extremely high pressures. However, the most recent paper announced the discovery of a substance that became superconducting at room temperature, but at much lower pressure.

This work would have constituted a great breakthrough in the field of superconductivity. However, we will show that serious questions arose regarding the data and analysis of these experiments. This has led to several papers by Dias and collaborators from the most prestigious science journals. In Section IV, we note that questions have also been raised about extensive plagiarism in Dias’ thesis. And in Section V we summarize the current status of Prof. Dias and his research.

Figure I.1: Ranga Dias, Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Physics and Astronomy, University of Rochester.

Ranga P. Dias was born in Sri Lanka and received his B.S. degree in physics from the University of Colombo. In 2013 he obtained his Ph.D. in physics at Washington State University where his thesis advisor was Choong-shik Yoo. Dias then had a postdoctoral position at Harvard University where he performed research on solid metallic hydrogen. Dias and his postdoctoral advisor Isaac Silvera placed a sample of hydrogen in a diamond anvil cell inside a cryostat. A diamond anvil cell contains two oppositely situated diamonds with polished tips, between which one may compress a sample to extreme pressure. They decreased the temperature to 3 Kelvin (3 degrees Celsius above absolute zero) and increased the pressure on their hydrogen sample to 4.95 megabars (Note: in this post we will use megabar and kilobar for pressure, where 1 megabar is 106 bar and 1 kilobar is 103 bar. Another standard unit for pressure is the Pascal or Pa; here, 1 GigaPascal or GPa = 109 Pa = 10 kilobars, represents about 10,000 times normal atmospheric pressure. Normal atmospheric pressure is equal to 1.03125 bars. Thus, a pressure of 4.95 megabars is almost 5 million times Earth’s atmospheric pressure). As the pressure increased, they took pictures of light reflected from the sample. At lower pressures the sample was transparent, as shown in the left-hand picture in Figure I.2. As the pressure was increased, the sample turned black; Dias and Silvera suggested that this meant that the hydrogen sample was superconducting. At the highest pressure the reflected light was shiny and lustrous. Dias and Silvera claim that this showed that hydrogen had formed a crystal.

Figure I.2: Reflected light from Hydrogen in Diamond Anvil Cell. As pressure increases (L to R), the sample goes from transparent, to black, to shiny. Dias and Silvera interpret this as a transition to a metallic hydrogen state.

This result would have been very impressive, as it would have confirmed the speculation by Wigner and Huntington nearly 90 years ago that hydrogen would transition to a metallic state under high pressure. Researchers had been looking for such a transition for many years. However, many scientists were not convinced that Dias and Silvera had definitely identified a metallic state of hydrogen. Alexander Goncharov speculated that Dias and Silvera may have seen reflections from aluminum oxide, which coats the tips of the diamonds in the anvil. And French physicist Paul Loubeyre asserted that the authors needed much more evidence before they could make an airtight case that they were producing metallic hydrogen. Harvard professor Silvera reported that he and Dias would be undertaking further experiments, but we know of no further publications from this group.

In 2017, Dias took a position as Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Physics and Astronomy at the University of Rochester. He is also a scientist at Rochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics. In his research, Dias utilizes diamond anvil cells to subject materials to extremely high pressures, and he uses laser systems to produce very low temperatures in samples via the technique known as laser cooling. In the past few years, he has concentrated on attempts to produce high-temperature superconducting materials. In Section II, we will briefly review the quest to produce substances that are superconducting at room temperatures and at relatively low pressures. In Section III, we will discuss the charges of scientific misconduct that have been leveled against Dias. In Section IV, we will review charges of plagiarism in Dias’ Ph.D. thesis and in some of his publications.

II: The Quest for Room-Temperature Superconductors

Conducting materials produce an electric current when an external voltage is applied. The relation between the external electric potential V, the current I and the resistance of the material R is given by Ohm’s Law, V = IR. The resistance of the material R varies with the temperature. As the temperature T of the material decreases, the resistance also tends to decrease. In 1911 the Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes discovered that for some substances, there is a “critical temperature” at which the resistance of the material drops very rapidly to zero. Kamerlingh Onnes was an expert on low-temperature phenomena, and he was investigating how properties of matter behave at extremely low temperatures. He was the first person to cool helium until it liquefied at a temperature of 4.15 Kelvin (4.15 K, or 4.15 degrees above absolute zero). Kamerlingh Onnes subsequently cooled liquid helium down to a temperature of 1.5 K, which was the lowest temperature ever achieved at that time.

Figure II.1: Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes. In 1911, he discovered the phenomenon of superconductivity.

Kamerlingh Onnes then studied the resistance of various metals at very low temperatures. In April 1911 he immersed a mercury wire in liquid helium and was shocked to find that at a temperature of 4.2 K, the resistance of the mercury wire suddenly went to zero. This is shown schematically in Figure II.2, where the resistance vs. temperature curve is shown for both a normal non-superconducting metal and a superconductor. Kamerlingh Onnes immediately understood the significance of his discovery and coined the effect “superconductivity.” For his work in low temperature studies, including the liquefying of helium and the discovery of superconductivity, Kamerlingh Onnes was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1913.

Figure II.2: Generic resistance vs. temperature curve. For a non-superconducting metal, the resistance decreases with temperature in Kelvin. For a superconductor, at some critical temperature TC the resistance suddenly drops to zero.

Since the work of Kamerlingh Onnes, scientists have studied the variation of resistivity with temperature. They identified several substances that display superconductivity, and have measured the ‘critical temperature’ TC at which superconductivity occurs. The critical temperature also depends on the pressure to which the system is subjected. Figure II.3 shows the critical temperature for a number of superconductors vs. the date that superconductivity was discovered, from 1911 until 2015. Note that the temperature scale is cut and redefined at 50 K. High temperature superconductors are generally defined as those that have critical temperatures above 77 K, the temperature where Nitrogen liquefies (denoted by arrow at right of figure). The color coding represents different classes of materials. Low-temperature or high-pressure metallic superconductors are displayed as green circles; these are labeled as BCS superconductors after the theoretical explanation of their behavior that was developed by John Bardeen, Leon Cooper, and John Robert Schrieffer. Cuprates, which contain copper oxide combined with other metallic elements in their molecules, are displayed as blue diamonds, and iron-based superconductors as yellow squares.

Figure II.3: Critical temperature TC for superconductors in degrees Kelvin vs. the year that superconductivity was discovered [Note that the temperature scale is cut at 50 K]. Until 1986, all superconductors had critical temperatures below 30 K. However, in 1986 a new class of superconductors was discovered and critical temperatures increased beyond 100 K. Until 2015, superconductors were discovered with critical temperatures up to 203 K, which is still only –70°C.

Although Kamerlingh Onnes discovered superconductivity in 1911, there was no microscopic theoretical understanding of this phenomenon until 1957, when Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer (BCS) published a paper that explained conventional superconductivity. Bardeen had pointed out in 1955 that a set of phenomenological equations called the London equations, with modifications from Pippard that introduced a scale parameter called a coherence length, would arise naturally in a theory that produced an energy gap between the ground and excited states. In 1956, Cooper calculated the properties of electron pairs subject to an attractive force between them (these are now called Cooper pairs). Bardeen and Cooper then collaborated with Robert Schrieffer to produce a successful microscopic theory of superconductivity. BCS superconductivity arises when Cooper pairs in a material form a condensate, in which many Cooper pairs act cooperatively, as though they formed a single entity. A notable success of BCS theory was that it reproduced the Meissner effect — when a substance makes a transition into the superconducting state, an electric current flows on the surface of that substance, such that it completely cancels any magnetic fields inside the body of the superconductor. In Fig. II.3, the substances labeled with green circles are materials whose superconducting properties are described by BCS theory.

From Fig. II.3 we see that before 1986, all superconducting substances had critical temperatures below 30 K. However, in 1986 Bednorz and Mūller discovered a new class of superconductors that involved ceramics called cuprates (substances containing copper oxide). Shortly after the first discovery by Bednorz and Mūller, additional superconducting substances were discovered which had critical temperatures above 90 K. What made these discoveries so profound, and earned Bednorz and Mūller the 1987 Nobel Prize in Physics, was that superconductivity could now be reached for some materials by cooling them with widely available liquid nitrogen, rather than requiring the much more arduous task of cooling with liquid helium. The most powerful electromagnets designed today use such high-temperature superconducting materials in their windings, for example, in large electromagnets designed for fusion reactors.

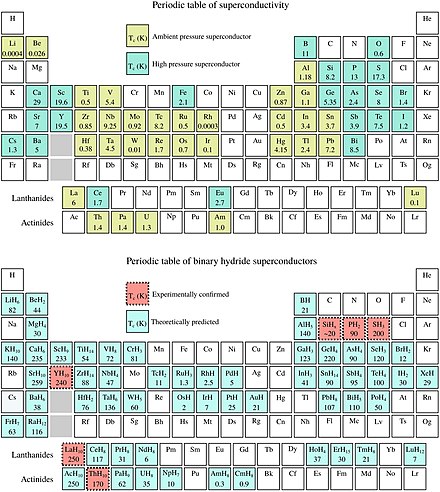

Figure II.4 shows a “periodic table” of superconducting elements. In the upper graph, ochre squares represent those elements that are superconducting at normal atmospheric pressures; blue squares represent elements that become superconducting at very high pressures. The lower graph shows elements that become superconducting when bonded with hydrogen. Pink squares are those that have been discovered experimentally, and blue squares are those that are predicted from theory to be superconducting.

Figure II.4: Upper table: Periodic Table of superconductors. Ochre = elements that become superconducting at atmospheric pressure; blue = elements that display superconductivity at high pressure. Lower table: Periodic table of binary hydride superconductors. Pink = elements experimentally confirmed to be superconducting when paired with hydrogen. Blue = elements whose binary hydrides have been theoretically predicted to be superconducting.

It was immediately clear that the cuprate substances found by Bednorz and Mūller could not be described by BCS theory. In fact, these new materials were ceramics, which are generally found to be insulators and not conductors. Furthermore, new materials were rapidly discovered that became superconducting at critical temperatures above 77 K, the temperature where nitrogen liquefies. This was extremely important: materials that become superconducting at temperatures lower than 77 K must be cooled with extremely expensive refrigerants such as liquid helium. For example, the magnets in most MRI machines are cooled with liquid helium. This is a very expensive process, as liquefying helium is costly plus helium is in very short supply.

After 1986, there was intense effort to discover materials that were superconducting at the highest temperatures. If one could find substances that became superconducting at or near room temperature, and that were relatively inexpensive and readily available, one could imagine a host of applications for these substances. First, one would not have to use liquid helium to cool the magnets in MRI machines or even liquid nitrogen to cool magnets in fusion reactors. Because superconductors have zero resistance, a current can be established in a superconductor and will persist for extremely long times – it is estimated that currents in superconducting coils could be maintained for up to 100,000 years. High-performance computers generate immense amounts of heat from the currents in their circuits. If computer circuits were made with superconductors, heat losses would become negligible and these computers would be much more sustainable. Superconducting substances could power electric cars, planes and magnetically levitated trains. Room-temperature superconductors could be used to power vehicles sent into space.

In recent years there has been much research into superconducting materials that contain hydrogen. When subjected to very high pressure, it is believed that hydrogen may be converted into a crystalline substance, and it is thought that this would cause these materials to become superconducting. In 2014, it was confirmed that hydrogen sulfide (H2S) would become superconducting at a critical temperature of 80 K, under a pressure of 1.5 megabars. In 2015, a group found that hydrogen sulfide under a pressure of 1.7 megabars became superconducting at a critical temperature of 203 K.

In this Section we reviewed the state of the art in high temperature superconductivity up to about 2015, when Ranga Dias and collaborators began their studies of superconducting systems. Scientists were finding new substances that would become superconducting at normal pressure and temperatures as high as 150 K. And other groups concentrated on achieving the highest possible superconducting temperatures but at extremely high pressure. The Holy Grail here was to find substances that were superconducting at room temperatures (roughly, temperatures of 280 K or higher). If these room temperatures were achieved only at very high pressures, research would continue in an effort to find related substances that could be made superconducting at room temperature and at pressures much closer to standard atmospheric pressure. Those who succeeded could hope to make a fortune by patenting their discovery; in addition, there would be scientific recognition for achieving the highest known temperatures for superconducting materials. Those who achieved the greatest success would be in line for awards, and potentially for a Nobel Prize if the discovery was sufficiently important.

III: Sensational Papers and Allegations of Misconduct:

Over the past several years, a number of papers co-authored by Ranga Dias have come under scrutiny. Most but not all of these papers involved research in high-temperature superconductivity with hydrides of various materials and at extremely high pressure. As of Feb. 2024, four of the papers co-authored by Dias have been retracted by the journals that initially published them. In this section we will review the history of retracted papers co-authored by Ranga Dias.

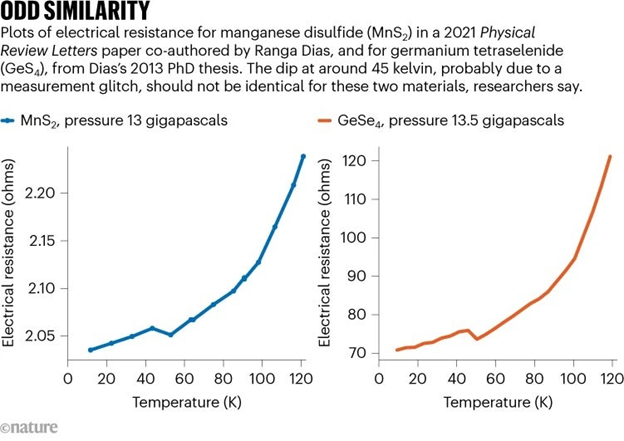

One paper was a study of resistance vs. temperature in Manganese Sulfide (MnS2), published in a 2021 article in Physical Review Letters (PRL). After James Hamlin, a professor at the University of Florida, found extensive amounts of plagiarism in Dias’ Ph.D. thesis (copied from Hamlin’s own thesis, and discussed in the following section), he began to search through papers published by Dias. Hamlin scoured these papers for evidence of plagiarism, but also for suspicious activity in the handling of data. Figure III.1 shows a comparison of resistance vs. temperature in Germanium Tetraselenide (GeSe4) (right), a substance studied in Dias’ 2013 Ph.D. thesis, and resistance studies of MnS2 from the PRL article (left). Hamlin discovered that the curves are virtually identical in shape, even though the absolute values of the resistance are quite different. Most striking is a sharp dip in the resistance at a temperature of about 45 Kelvin; this seems to be a glitch in the measurements. There is no known physical reason why the two substances should show a nearly identical behavior, nor should an identical glitch occur in both substances.

Figure III.1: Resistance vs. temperature curves claimed for two substances. Manganese disulfide (left) from a 2021 PRL paper, and Germanium Tetraselenide (right) from R. Dias’ 2013 thesis. The two curves are nearly identical, even containing an identical dip at around 45 Kelvin which is thought to be a measurement glitch.

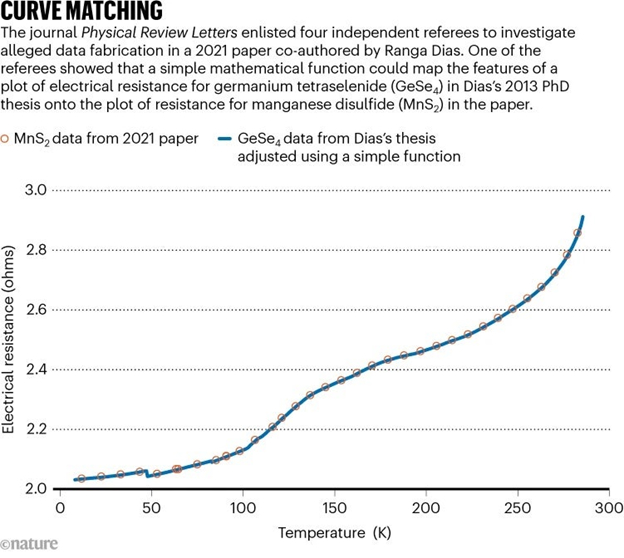

Hamlin then communicated his concerns both to the editors of Physical Review Letters and to Dias’ co-authors on that paper. One of those co-authors, Simon Kimber, immediately requested that the paper be retracted. “The moment I saw the comment, I knew something was wrong. There is no physical explanation for the similarities between the data sets,” Kimber told a journalist at Nature magazine. After being shown the odd similarity between the resistance vs. temperature curves, PRL confirmed it was investigating the paper. On March 20, 2023 PRL issued an ‘expression of concern’ regarding that paper. PRL then had four referees study that paper and the claims made regarding it. Two of the four referees concluded that “The only explanation of the similarity” between the GeSe4 and MnS2 plots is that data were taken from Dias’ thesis and used in the 2021 paper. One of the reviewers of the PRL paper produced a “smoking gun” in this investigation. They found a simple mathematical function that could map the manganese data onto the germanium data. This is shown in Figure III.2, where the open circles are the resistance vs. temperature points for the MnS2 data from the 2021 PRL paper. The solid curve is the GeSe4 data from Dias’ thesis, adjusted with this mathematical function. This adjustment produces perfect agreement between the two data sets.

Figure III.2: One of the PRL referees found a simple mathematical function that would map the resistance vs. temperature curve from Dias’ 2013 Ph.D. thesis on GeSe4 (solid curve) onto the MnS2 data from the 2021 PRL paper (dots). The resulting curves are essentially identical.

On Aug. 15, 2023, PRL issued a retraction of the article by Dias and collaborators. PRL reported that the American Physical Society (APS) Head of Ethics and Research Integrity had commissioned an internal investigation that resulted in three reports from four independent experts. They expressed serious doubts about the origins of three low-temperature resistance curves published in that paper. Given those concerns, nine of the ten authors of that paper deemed it appropriate to retract that article. However, Ranga Dias did not agree to retract the Letter and informed the editors of PRL that he stood by the data published in that paper.

Dias continued to assert that the claims in the paper on manganese sulfide were still valid, despite the determination to retract the paper. Dias claimed that his collaborators had introduced errors into the figures when the data was processed using Adobe Illustrator. “Any differences in the figure resulting from the use of Adobe Illustrator software were unintentional and not part of any effort to mislead or obstruct the peer review process,” said Dias. However, critics of Dias stated that his claims were “both inadequate and disappointing.” One of the reviewers of the paper said that there had been “no mention of Adobe Illustrator in the months of back and forth between the authors of the paper, Dr. Hamlin and the editors of Physical Review Letters.”

A second paper published by Dias and collaborators was a 2020 blockbuster article that claimed to have found a substance, carbonaceous sulfur hydride (CSH), that became superconducting at about 287 K (or 14 Celsius) and a pressure of 2.67 megabars, equivalent to nearly 40 million pounds per square inch. This was a collaboration between a University of Rochester group led by Ranga Dias and a group at the University of Nevada led by Ashkan Salamat. This result, if true, would constitute the first room-temperature superconductor discovery. Previously, in 2015 a German group had reported achieving superconductivity in hydrogen sulfide (H2S) at 203 K, and in 2019 two groups had reported finding superconductivity in samples of Lanthanum superhydride (LaH10). Drozdov et al. found superconductivity at 250 K, and Somayazulu et al. achieved superconductivity at 260 K; at that time, each of these was a record high critical temperature for superconductors. However, all groups had achieved superconductivity at very high pressures; 1.70 megabars for the Drozdov group and 2.0 megabars for the Somayazulu group, while the H2S samples became superconducting at 1.55 megabars.

However, the discovery of a substance that was superconducting at room temperature was a major step in achieving the goal of a substance that would achieve superconductivity at room temperature and normal atmospheric pressure. As a result, the announcement by Dias and collaborators made the cover of the prestigious Nature journal with the headline “Turning up the heat,” and was praised in a New York Times article with the headline “Finally, the first room-temperature superconductor.” However, such an important claim naturally subjected the paper to much scrutiny, while people tried to replicate or extend this result. The first issue with the CSH paper was discovered by Jorge Hirsch of UC San Diego. He found that a quantity called the magnetic susceptibility plotted vs. temperature reported by Dias and collaborators showed a very strange behavior. Just below the superconducting temperature Tc, the susceptibility increased rapidly, while the standard behavior would have been for the susceptibility either to flatten out or to increase very gradually. Hirsch found a similar unusual behavior in the magnetic susceptibility in a 2009 paper on superconductivity in Europium.

When Hirsch pointed this behavior out to James Hamlin, one of the authors of the Europium paper, Hamlin discovered a flaw in his group’s measurements. One of Hamlin’s collaborators re-ran the Europium studies and found no superconductivity, and the 2009 Europium paper was subsequently retracted. Hamlin then contacted Dias and one of his co-authors on the CHS paper, Ashkan Salamat. In the meantime, no other experimental group had been able to replicate Dias’ synthesis, much less measure superconductivity in CSH. Also, Dias had refused to publish the ‘raw’ data from the CHS study. However, in Dec. 2021, Dias and Salamat posted a preprint of the complete dataset for their magnetic susceptibility measurements on the condensed matter archive (cond-mat arXiv:2111.15017v2).

But this dataset raised as many questions as it answered. Scientists noted that correlations between the noise appearing in the raw data and noise in the background data were not in agreement. When they contacted Dias, he stated that the background signal had not been measured (as was stated in the Nature article), but it had been “constructed.” Jorge Hirsch carried out a detailed study of the background and signal in the CHS study. He found a mathematical function that could exactly reproduce the “data” from that study. This cast great doubt on the data from this experiment, as it implied that the background had not been measured but instead generated using a mathematical function.

The non-standard treatment of the background, plus issues that arose in the behavior of their electrical resistivity, led to the CHS paper in Nature being retracted on Sept. 26, 2022. In the retraction note, the editors of Nature outlined the reasons for retracting this paper. “Some key data processing steps— namely, the background subtractions applied to the raw data used to generate the magnetic susceptibility plots in Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 7d—used a non-standard, user-defined procedure. The details of the procedure were not specified in the paper and the validity of the background subtraction has subsequently been called into question. The authors maintain that the raw data provide strong support for the main claims of the original paper.” Even though none of the authors of this paper agreed to the retraction, the editors of Nature were convinced that the non-standard issues with data handling justified the retraction, particularly since the paper had claimed that the backgrounds had been measured, where in fact they had been constructed. The retraction note stated, “Nevertheless, we are of the opinion that these processing issues undermine confidence in the published magnetic susceptibility data as a whole, and we are accordingly retracting the paper.”

The Rochester – Nevada group had also published a paper in the journal Chemical Communications expanding on their studies of CHS. However, skeptics found that this article also suffered from the same defects as the Nature article. That journal convened a group of reviewers to study the claims in the paper and those from critics of the data handling. As a result, the paper in Chem. Commun. was retracted in December 2023. The retraction reads “We have lost confidence in the origin of the electrical transport measurements, and therefore all conclusions deduced from the electrical measurements, including the superconductivity properties are uncertain. Therefore, this article is being retracted in order to avoid misleading readers, and to protect the accuracy and integrity of the scientific record.” All of the 12 authors of this paper agreed to the retraction, except for Ranga Dias who did not respond to the journal editors.

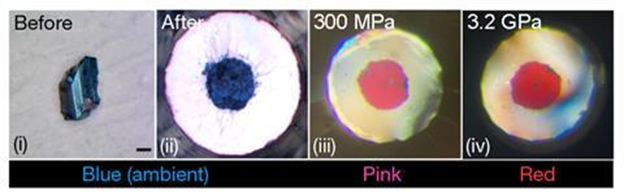

Yet another problematic paper was a March, 2023 article in Nature regarding the discovery of superconductivity in Nitrogen-doped systems of Lutetium Hydride (Lu-N-H). Again, this paper announced a major breakthrough in superconductivity studies. The authors claimed to have discovered superconductivity at true room temperatures – in this case, at a maximum temperature of 294 K or 21o Celsius. Although the pressures applied to the system were still reasonably high (around 2 kilobars, equal to a pressure of 145,000 pounds per square inch), those pressures were much lower than in previous systems that had shown superconductivity at high temperatures. And this result would represent the highest critical temperature ever achieved for a superconducting substance. Figure III.3 shows results of microphotographs of light reflected from the Lu-N-H sample (circle in center of figure). At initial low pressures (ii) the reflected light is blue, which the authors claim indicates a non-superconducting metallic phase for the sample. However, at a pressure of 3 kilobars (300 MPa) (iii) the reflected light is pink, which the research group interpreted as a sign that the sample is superconducting. At higher pressures of 32 kilobars (3.2 GPa) (iv) the reflected light is red, indicating that the sample is no longer superconducting. [Note: We do not understand why these changes in color are signs that the sample has entered and then left a superconducting state].

Figure III.3: Figure from the paper of Dasenbrock-Gammon et al., showing microphotographs of light reflected from a Lu-N-H sample (central circle) at different pressures. At low pressures the reflected light is blue (ii), typical of a metallic non-superconducting state. At a pressure of 3 kilobars (iii) the light is pink, indicating that the sample has turned superconducting. At higher pressure of 32 kilobars (iv), the reflected light is red, indicating that the sample is no longer superconducting.

However, the community of condensed matter physicists was keenly aware that the earlier 2020 paper by the group led by Ranga Dias at the University of Rochester and Ashkan Salamat at the University of Nevada had been retracted. Thus, this subsequent paper was subjected to intense scrutiny. Some critics suggested that the reflected light shown in Fig. III.3 could have been light reflecting from aluminum oxide, a substance used to coat the diamonds in the anvil that was used to achieve the high pressures in this study.

In May 2023 James Hamlin from the University of Florida and Brad Ramshaw of Cornell contacted the editors of Nature with their concerns about the data in the Lutetium Hydride paper. In September 2023 Nature marked the paper for review due to questions about “the reliability of data presented.” The paper underwent further review led by the staff at Nature, and a retraction notice was issued on Nov. 7, 2023. This note states that eight of the eleven authors of the paper “Expressed the view as researchers who contributed to the work that the published paper does not accurately reflect the provenance of the investigated materials, the experimental measurements undertaken and the data protocols applied. The above-named authors have concluded that these issues undermine the integrity of the published paper. In addition, and separately, concerns have been independently raised with the journal regarding the reliability of the electrical resistance data presented in the paper. An investigation by the journal and post-publication reviews have concluded that these concerns are credible, substantial and remain unresolved.” Ashkan Salamat was one of the co-authors who requested that the article be retracted. Ranga Dias was one of the three authors who did not respond to requests from Nature asking whether they agreed or disagreed with the conclusions of the Nature review. The eight authors who agreed to the retraction told Nature that “Dr. Dias has not acted in good faith in regard to the preparation and submission of the manuscript.”

Despite the fact that four of the most prominent papers led by Ranga Dias have been retracted, Dias still has some supporters. Prior to the retraction of the paper on superconductivity in N-doped Lutetium Hydride, the University of Rochester had conducted two preliminary investigations of Dias. University of Rochester spokesperson Sara Miller said that the first of these preliminary investigations had “determined that there was no evidence that supported the concerns.” She also said that Rochester had “considered the matter of the September 2022 retraction of the Nature paper [on superconductivity in a CSH system] and came to the same conclusion.” This conclusion seemed a bit strange as the editors at both Physical Review Letters and Nature had determined that the papers they retracted showed signs of scientific misconduct. However, following the retraction of the paper claiming superconductivity in the Lu-N-H system, Rochester initiated a “comprehensive investigation” of Dias, involving experts not affiliated with the university. As of Feb. 2024, it is not known whether this investigation is still ongoing, and a university spokesperson said that the University of Rochester “had no plans to make the findings of the investigation public.” However, Rochester has removed YouTube videos it produced in March 2023 that featured university officials praising the “superconductivity breakthrough” in Prof. Dias’ now-retracted article.

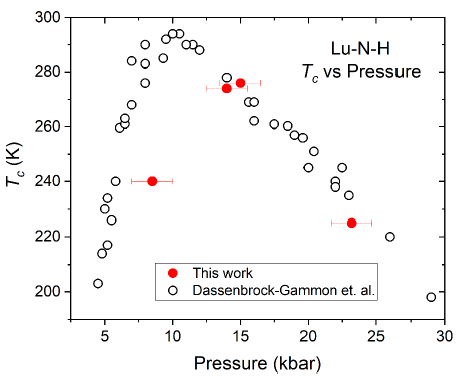

Dias also has support from Russell Hemley, a condensed-matter experimentalist at the University of Illinois – Chicago. Hemley received a sample of the N-doped Lutetium Hydride from the Dias group and studied the dependence of the resistance of this system on temperature and pressure. Hemley’s group submitted a preprint to arXiv in June 2023 (cond-mat arXiv:2306.06301), claiming that his group had verified some key findings claimed by the group led by Dias and Salamat. Figure III.4 shows the superconducting critical temperature TC for Lu-N-H in Kelvin vs. pressure in kilobars. The open circles are the results from Dassenbrock-Gammon et al. (the group led by Dias and Salamat), while the red circles are results obtained by Hemley’s group. Not only does Hemley report finding superconductivity at room temperatures in the Lu-N-H system, but the superconducting critical temperatures he obtained are in reasonably good agreement with those of the Dias-Salamat group. It should be noted that as of Feb. 2024, the preprint by the Hemley group has not been published in a refereed journal.

Figure III.4: Superconducting critical temperature TC in Kelvin vs. pressure in kilobars for a sample of N-doped Lutetium Hydride. Open circles are from the results of Dassenbrock-Gammon et al. (a retracted paper from Nature), while the solid red circles are obtained by Hemley (2023 preprint). The Hemley results appear to confirm the claims of the Rochester-Nevada group regarding room-temperature superconductivity in this system.

IV: Ranga Dias’ Ph.D. Thesis:

Physicist James Hamlin from the University of Florida began investigating Ranga Dias’ Ph.D. thesis, which was completed in 2013 under the supervision of physics professor Choong-shik Yoo at Washington State University. Hamlin alleges that he found extensive plagiarism in Dias’ thesis from his own 2007 thesis at Washington University of St. Louis. After discovering the plagiarism by Dias, Hamlin also found examples of misconduct in papers published by Dias. Figure IV.1 shows one example of the plagiarism found by Hamlin. At left is a sample of text from pages 64 and 66 of Hamlin’s thesis, and at right the identical wording found in a preprint by Dias and Salamat on the condensed matter arXiv (cond-mat arXiv:2111.15017v2). The reproduction of words in this case is far from trivial as it involves the detailed description of experimental setup and procedures in experiments carried out by independent teams in different locations at different times. Hamlin had copies of his thesis and that of Dias examined by Lisa Rasmussen, a research ethicist at the University of North Carolina – Charlotte. Rasmussen concluded that there was “obvious” plagiarism in the thesis of Dias. Also, the thesis of Dias contained material that had been copied from a 1999 paper by Dias’ thesis advisor Choong-shik Yoo. In April 2023, an article in Science magazine reported that at least 6,300 words, or 21% of Dias’ thesis, had been plagiarized.

Figure IV.1: An example of plagiarism that occurred in work co-authored by Ranga Dias. Left: an excerpt from the 2007 Ph.D. thesis of James Hamlin. Right: Identical passages from a preprint on manganese sulfide co-authored by Dias. Allegations have also been made that Dias’ 2013 Ph.D. thesis contains a significant fraction of plagiarized material.

This information came from James Hamlin and Simon Kimber, who had used online tools together with searches of articles in Google Scholar to identify phrases that Dias had copied from other sources without attribution. Kimber had been a co-author on papers by Dias; he first became interested in the question of plagiarism when James Hamlin pointed out to him striking similarities between a figure published in a 2021 article in Physical Review Letters by Dias, Kimber and others, and a figure published in Dias’ thesis on an entirely different substance (this is shown in Fig. III.1). Hamlin and Kimber claim to have found examples of plagiarism from 17 different sources. A spokesperson for the University of Rochester responded that most of the plagiarism in the thesis and articles occurred in sections dealing with methodology or background information. Although this might appear to mitigate somewhat the severity of the plagiarism, it does not completely exonerate Dias. Lisa Rasmussen characterized the plagiarism issue as “It helps to paint a picture of someone as not really caring about standards. It suggests that they don’t mind cutting corners; that they may not have as many original ideas as they’re presenting themselves to have.” Furthermore, the extent of the plagiarism, amounting to 21% of the text of the thesis, is very concerning. As of 2023, Dias had submitted a request to correct his thesis, and Washington State University’s Academic Integrity Hearing Board was investigating the circumstances of his dissertation.

V: Summary

Ranga Dias has had a turbulent career as a scientific researcher. Already, four of his papers in prestigious journals have been retracted after the journal editors were notified about problems with handling of the data. It was felt that the non-standard data analysis methods used in these papers led to serious questions as to whether the conclusions could be trusted. In the second paper (claims of room-temperature superconductivity in a carbonaceous sulfur hydride sample), all of the authors disagreed with the decision by the journal Nature to retract that article. However, in the 2021 paper analyzing manganese sulfide Dias was the only one of ten authors who did not agree to retracting that article. In the 2023 Nature article claiming the highest temperature superconducting sample eight of the eleven authors (not including Dias) agreed to the retraction. Finally, the article in Chem. Commun. discussing superconductivity in the CSH sample was retracted in December 2023 with 11 of the 12 authors agreeing to the retraction, except for Ranga Dias who did not respond to the journal editors.

After the retraction of the March 2023 Nature article claiming the observation of superconductivity in a sample of Lutetium Hydride doped with Nitrogen, the eight authors who agreed to the retraction told the Nature editors that “Dr. Dias has not acted in good faith in regard to the preparation and submission of the manuscript.” Note that this included graduate students and postdocs from Dias’ research group at the University of Rochester. Those who agreed to the retraction notice also included students from the group led by Ashkan Salamat, a professor of physics at the University of Nevada. Salamat was among those who agreed to the retraction. During their earlier research on CSH, Dias and Salamat founded a company called Unearthly Materials. This company was intended to produce commercial superconducting materials from their research, and to generate revenue from these ‘breakthrough’ discoveries. Dr. Salamat was the president and CEO of this company; however, Salamat is no longer employed at Unearthly Materials, although the company’s website still proudly lists both Dias and Salamat as co-founders and extols the importance of their retracted research.

Initially, questions about scientific misconduct in research papers published by Ranga Dias arose from a small number of condensed-matter physicists who found troubling signs of fraud in data samples released by the Rochester-Nevada research groups. These scientists communicated their concerns to journals such as Physical Review Letters and Nature. Those journals then contacted groups of expert reviewers, who scrutinized the research papers and the claims from the skeptics. The reviewers focused on the data, and whether the research paper provided an honest summary of how the data were handled. Eventually, the journal editors were convinced that the papers had problems that raised serious doubts about the claims that had been made; they then issued a retraction of the work.

A particularly damning fact was that, after a paper in Nature was retracted in November 2023, the eight researchers who agreed to the retraction notice charged Prof. Dias with “not acting in good faith.” This included graduate students and postdocs from Dias’ own group at the University of Rochester, in addition to faculty and students from Dias’ collaborators at the University of Nevada. This would seem to provide solid proof that Ranga Dias’ actions were examples of scientific misconduct.

The one open question in this saga is the work from Russell Hemley and his collaborators at the University of Illinois – Chicago. Hemley obtained samples of Lutetium-Nitrogen-Hydride from Dr. Dias, and he performed experiments using these samples. Hemley’s group claims to have confirmed the report of superconductivity in the Lu-N-H system, and furthermore claims to have obtained roughly the same superconducting critical temperatures as a function of pressure (see Fig. III.4, taken from the preprint by Hemley’s group, cond-mat arXiv:2306.06301). Hemley’s results suggest that, despite the serious issues with data handling and scientific misconduct by Ranga Dias, the room-temperature superconductivity claimed by Dias and his collaborators may yet be confirmed. This seems highly unlikely but still possible; we will update this post when other groups either confirm or fail to confirm these claims of room-temperature superconductivity at relatively low pressures. In the meantime, this saga seems to provide another example, similar to that we covered in our Cold Fusion post, where the lure of prize-winning discoveries has led to sloppy research, inadequately described in publications, with apparently spectacular results that cannot be taken seriously.

Source Material:

Wikipedia, Ranga P. Dias https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ranga_P._Dias

Wikipedia, Superconductivity https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superconductivity

Wikipedia, High Temperature Superconductivity https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High-temperature_superconductivity

Wikipedia, Meissner Effect https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meissner_effect

J. Bardeen, L.N. Cooper and J.R. Schrieffer, Microscopic Theory of Superconductivity, Physical Review 106, 162 (1957) https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstract/10.1103/PhysRev.106.162

R.P. Dias and I.F. Silvera, Observation of the Wigner-Huntington Transition to Metallic Hydrogen, Science 355, 715 (2017); https://www.science.org/doi/epdf/10.1126/science.aal1579

E. Wigner and H.B. Huntington, On the Possibility of a Metallic Modification of Hydrogen, J. Chem. Phys. 3, 764 (1935) https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jcp/article/3/12/764/203469/On-the-Possibility-of-a-Metallic-Modification-of

Davide Castelvecchi, Physicists Doubt Bold Report of Metallic Hydrogen, Nature 542, 17 (2017) https://www.nature.com/articles/nature.2017.21379

Jonathan Amos, Claim Made for Hydrogen ‘Wonder Material,’ BBC Jan. 27, 2017 https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-38768683

D. Durkee et al., “Colossal density-driven resistance response in the negative charge transfer insulator MnS2,” [Retracted article] Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 016401 (2021).

Randall Kamien, Expression of Concern: “Colossal density-driven resistance response in the negative charge transfer insulator MnS2,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 016401 (2021) https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.130.129901

D. Durkee et al., Retraction: “Colossal density-driven resistance response in the negative charge transfer insulator MnS2,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 016401 (2021) https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.079902

Daniel Garisto, Plagiarism Allegations Pursue Physicist Behind Stunning Superconductivity Claims, Science News, April 13, 2023; https://www.science.org/content/article/plagiarism-allegations-pursue-physicist-behind-stunning-superconductivity-claims

Daniel Garisto, Controversial Physicist Faces Mounting Accusations of Scientific Misconduct, Nature News, July 25, 2023 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-02401-2 ; reprinted in Scientific American Sept. 2023 https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/controversial-physicist-faces-mounting-accusations-of-scientific-misconduct1/

E. Snider et al., Room-Temperature Superconductivity in a Carbonaceous Sulfur Hydride (Retracted article), Nature 586, 373 (2020) https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2801-z

Retraction Note, E. Snider et al., Room-Temperature Superconductivity in a Carbonaceous Sulfur Hydride (Sept 26, 2022). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-05294-9

J.E. Hirsch, “Comment on ‘Carbon Content Drives High Temperature Superconductivity in a Carbonaceous Sulfur Hydride Below 100 GPa’ by G.A. Smith, I.E. Collings, E. Snider, D. Smith, S. Petitgirard, J.S. Smith, M. White, E. Jones, P. Ellison, K.V. Lawler, R.P. Dias and A. Salamat, Chem. Commun., 2022, 58. 9064,” Chem. Commun. 59, 5765 (2023) https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlepdf/2023/cc/d2cc05277f

G.A. Smith et al., Carbon Content Drives High Temperature Superconductivity in a Carbonaceous Sulfur Hydride Below 100 GPa, [Retracted Article] Chem. Commun. 58, 9064 (2022) https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2022/cc/d2cc03170a

Retraction: G.A. Smith et al., Carbon Content Drives High Temperature Superconductivity in a Carbonaceous Sulfur Hydride Below 100 GPa, Chem. Commun. 60, 1047 (2024) https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2024/cc/d3cc90410e

M. Debessai et al., Pressure-Induced Superconducting State of Europium Metal at Low Temperatures, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 197002 (2009); Retracted PRL 127, 269902 (2021). https://journals.aps.org/prl/pdf/10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.197002

R.P. Dias and A. Salamat, Standard Superconductivity in Carbonaceous Sulfur Hydride, cond-mat arXiv:2111.15017v2.

N. Dasenbrock-Gammon et al., “Evidence of near-ambient superconductivity in a N-doped lutetium hydride,” [Retracted Article] Nature 615, 244 (2023) https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-05742-0

Retraction Note: “Evidence of Near-Ambient Superconductivity in a N-Doped Lutetium Hydride, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06774-2#article-info

Yinwei Li et al., “The metallization and superconductivity of dense hydrogen sulfide,” Journal of Chemical Physics. 140, 174712 (2014) https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jcp/article/140/17/174712/317181/The-metallization-and-superconductivity-of-dense

A. P. Drozdov et al., “Conventional superconductivity at 203 Kelvin at high pressures in the sulfur hydride system,” Nature 525, 73 (2015) https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14964

A. P. Drozdov et al., “Superconductivity at 250 K in lanthanum hydride under high pressures,” Nature 569, 528 (2019) https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1201-8

M. Somayazulu et al., “Evidence for superconductivity above 260 K in lanthanum superhydride at megabar pressures,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 027001 (2019) https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.027001

Stuart Thomas, Superconductivity Warms Up, Nature Electronics 3, 658 (2020) https://www.nature.com/articles/s41928-020-00507-3

K. Chang, Finally, the First Room-Temperature Superconductor, New York Times Oct. 24, 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/14/science/superconductor-room-temperature.html

K. Chang, Superconductor Scientist Faces Investigation as a Paper is Retracted, New York Times Aug. 15, 2023 https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/15/science/retraction-ranga-dias-rochester.html

K. Chang, Room-Temperature Superconductor Discovery is Retracted, New York Times, Nov. 7, 2023 https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/07/science/superconductor-retraction-nature-paper.html

N.P. Salke et al., Evidence for Near Ambient Superconductivity in the Lu-N-H System, cond-mat arXiv:2306.06301

Kit Chapman, Third Room Temperature Superconductivity Paper Retracted as Group’s Claims Lie in Tatters, Chemistry World Nov. 9, 2023 https://www.chemistryworld.com/news/third-room-temperature-superconductivity-paper-retracted-as-groups-claims-lie-in-tatters/4018402.article