December 15, 2023

I. Introduction: “Plenty of Room at the Bottom”

In 1959 Richard Feynman (see Fig. I.1), a professor of physics at Caltech and one of the great scientific geniuses of the 20th century, gave a talk at an American Physical Society meeting called “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom: An Invitation to Enter a New Field of Physics.” In that talk, Feynman considered the possibility that scientists might manipulate individual atoms, and that one might think of constructing machines that were orders of magnitude smaller than were known at that time. Feynman was particularly interested in how one might construct incredibly small machines, how methods of mechanization would scale as one moved to smaller and smaller length scales, and what were the physical limits of the size of transistors or other electric circuit elements.

Figure I.1: Richard Feynman, a physicist who was one of the great geniuses of the 20th century. He introduced the notion of miniaturization and of atomic-level machines decades before they were invented.

We had heard of Feynman’s talk, and were aware of advances in miniaturization over the following decades. For example, in 1970 Arthur Ashkin introduced the concept of optical tweezers for manipulating individual cells or bacteria; Ashkin won the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics for this suggestion. In 1981 Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer at IBM Zūrich invented the scanning tunneling microscope, for which they received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1986. In 1993 the first atomic force microscope was developed. These and other inventions allowed researchers to manipulate matter at atomic and molecular levels. We were under the impression that Feynman’s talk had galvanized scientists into developing the field of nanotechnology. It turns out that we were quite wrong about this.

As it happened, for decades very few people knew about Feynman’s talk on miniaturization. Initially, no copies of Feynman’s speech were available; Feynman himself stated that he gave the talk off the top of his head with no notes. One member of the audience brought a tape recorder and subsequently made an edited transcript. The talk was reprinted in 1960 in Caltech’s Engineering and Science. In his talk, Feynman issued two challenges to the audience. The first involved a challenge to construct a working motor that was orders of magnitude smaller than conventional motors. The second challenge was to reduce the scale of letters so that the entire Encyclopedia Britannica could be “written” onto the head of a pin.

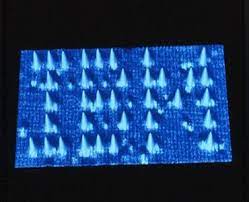

Anthropologists have studied the effect of Feynman’s lecture on the subsequent development of nanotechnology. To our surprise, they found that this amazing lecture had almost no effect on scientists studying atomic-level phenomena. Feynman’s lecture was only re-discovered in the 1980s. The history of nanotechnology has subsequently been “re-written” so that it connects to Feynman’s 1959 lecture, even though the pioneers in this field were unaware of the prescient ideas in this talk. In Feynman’s 1959 lecture he suggested “I am not afraid to consider the final question as to whether, ultimately – in the great future – we can arrange the atoms the way we want; the very atoms, all the way down! What would happen if we could arrange the atoms one by one the way we want to?” Well, 30 years later in 1989 scientist Don Eigler at IBM Labs used a custom-built microscope to manipulate 35 Xenon atoms on a surface, so that the atoms reproduced the IBM logo; this is shown in Figure I.2.

Figure I.2: In 1989, an IBM scientist used nanotechnology to manipulate 35 Xenon atoms on a surface so that they spelled out the IBM logo.

So, Richard Feynman’s revolutionary ideas have come to fruition. We now have microscopes, tiny machines, and nano-scale “tweezers” that allow us to manipulate particles at exceptionally small distance scales. As we will discuss, efforts to reduce the scale of electrical circuit elements gave rise to a massive fraud that is the subject of the following sections.

II: Jan Hendrik Schön and Organic Semiconductors and Superconductors

Bell Laboratories, headquartered in Murray Hill, New Jersey, has for nearly a century been one of the most important scientific research institutions in the world. Research there has led to ten Nobel Prizes and some of the leading developments in electronics and computer science. Among those developments are the transistor, radio astronomy, the laser, the photovoltaic cell (used today in solar panels), the charge-coupled device (CCD, used in many digital cameras), information theory, the Unix computer operating system, and some of the most widely used programming languages. The story we are about to tell served as a black mark on Bell Labs’ sterling reputation at the turn of this century.

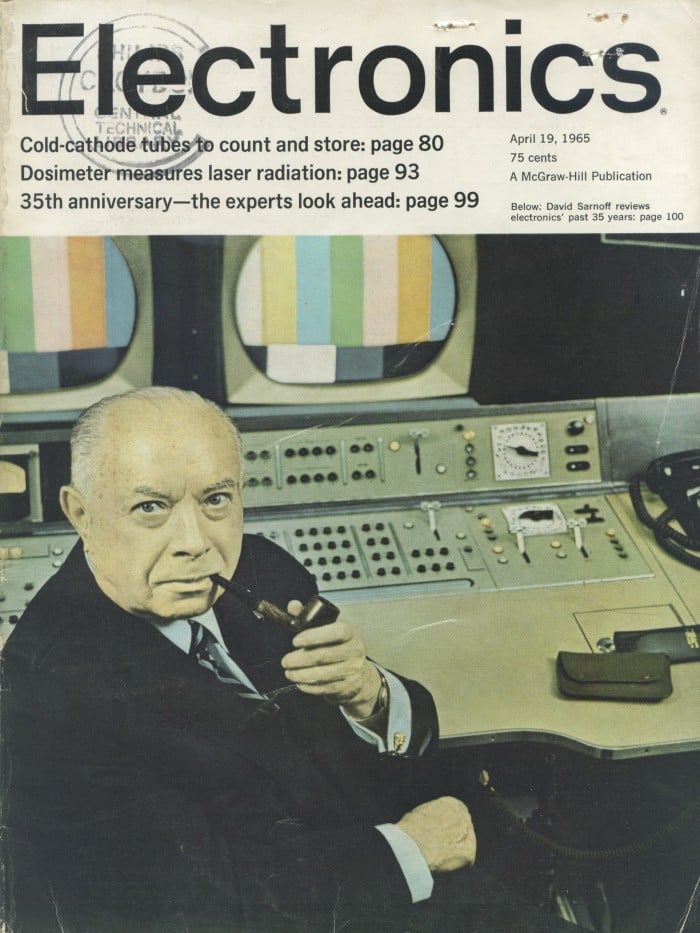

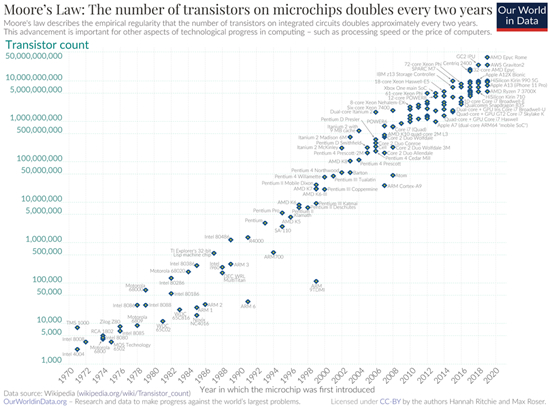

The hiring of Jan Hendrik Schōn at Bell Laboratories was the result of discussions about novel methods for constructing circuit elements. At present the circuit elements in computers are constructed using silicon. The cost of computers and their computing power is related to the number of transistors that can be accommodated on an integrated circuit, a microchip. In 1965 Gordon Moore, the co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor and of Intel, noted that the number of components that could be produced on an integrated circuit was doubling at a fairly constant rate. Eventually Moore settled on a doubling every two years of the number of components that could be produced on a single chip. Moore speculated that this trend would continue into the foreseeable future; this trend is known as Moore’s Law and has been fairly constant over the past five decades. He also noted that the cost of an integrated circuit would drop by a factor of two every two years, and this has also proved to be qualitatively true. Figure II.1 shows the cover of the April 1965 Electronics magazine, where Moore’s Law first appeared. Figure II.2 plots the number of transistors that can be accommodated on a single microchip as a function of time, on a semi-logarithmic plot. The plot of transistor count vs. time follows rather closely the straight-line semi-logarithmic behavior predicted by Moore’s Law.

Figure II.1: The cover of the April 1965 Electronics magazine; this issue included the observation of the number of transistors that can be fit onto an integrated circuit vs. time, now known as Moore’s Law.

Figure II.2: A graphic depiction of Moore’s Law. This is the observation that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit doubles every two years. This plot shows the number of transistors on an integrated circuit over a 50-year period from 1970 to 2020.

Moore’s Law is not a physical law but simply an empirical correlation observed by Gordon Moore. From Fig. II.2, we see that the number of transistors that can be produced on a microchip has agreed quite well with Moore’s Law over a 50-year period. However, we also know that Moore’s Law cannot be sustained indefinitely unless there are fundamental changes in the construction of computer circuits. At present, transistors are laid down on a microchip substrate made of silicon. We are currently approaching a physical limit on the size of a transistor that can be produced on silicon. In 2014, Intel produced chips where the length of a single transistor was 14 nanometers. The next size reduction to 10 nanometers was scheduled for two years later, but was not introduced until 2019. When the physical limit on transistor size is reached it will not be physically possible to create even smaller transistors on silicon, and Moore’s Law will have broken down.

Researchers at Bell Labs believed that plastics might prove to be a suitable material for fabricating circuit elements that might be even smaller than could be produced on silicon. Much of the material in the following sections is taken from the book Plastic Fantastic: How the Biggest Fraud in Physics Shook the Scientific World, by Eugenie Samuel Reich. We also recommend two books on fraud in science, On Fact and Fraud: Cautionary Tales from the Front Lines of Science, by David Goodstein, and Betrayers of the Truth: Fraud and Deceit in the Halls of Science, by William Broad and Nicholas Wade.

Bertram Batlogg, the head of the Department of Materials Physics at Bell Labs, was an expert in high-temperature superconductivity. His group hired chemist Christian Kloc, who was an expert in crystallizing novel substances. To complete their research group, they needed to hire an expert in semiconductors. They eventually settled on Jan Hendrik Schön (see Fig. II.3). He had finished his doctorate at Konstanz University in Germany with Ernst Bucher as his thesis advisor. Schön’s research there had focused on copper gallium selenide (CGS) semiconductors. He mainly worked with lasers and studied photoluminescence (release of light) when CGS samples were irradiated with laser light. Christian Kloc had been a postdoctoral researcher with Bucher at Konstanz before being hired by Bell Labs.

Figure II.3: Physicist Jan Hendrik Schön, who was hired in 1997 to do research on organic circuit elements at Bell Laboratories.

In 1997, Schön was hired as an intern at Bell Labs working in Bertram Batlogg’s group. He was provided with organic crystals produced by Christian Kloc, and his research project was to investigate the possibility that organic crystals could be used to produce tiny circuit elements that could be used for integrated circuits. At first the group used crystals of sexithiophene. They attached gold contacts to the crystals and constructed a gate electrode out of Kapton film, a substance that had plastic on one side and metal on the other. The plastic side was held against the crystals while the metal side was connected to electrical inputs.

The Bell Labs group was attempting to use organic crystals to create a field-effect transistor or FET. A schematic picture of a field-effect transistor is shown in Figure II.4. In an FET, a voltage is applied to a gate which is usually connected to the body of the transistor through an oxide insulating layer. When the voltage is applied, a current flows between the source and drain terminals. Depending on the material used, an FET can use either electrons as charge carriers (n-channel) or “holes” (electron absences) that move through a sea of electrons (p-channel).

Figure II.4: A schematic picture of a field-effect transistor or FET. A gate is placed on top of a semiconductor; the gate separates the source and drain terminals. When a voltage is applied to the gate, current can flow from source to drain. Depending on the material, the current can either consist of electrons (n-channel), or ‘holes’ in an electron sea (p-channel).

Batlogg and Schön obtained some promising results showing that they could produce effects using Kloc’s crystals and a gate constructed out of a Kapton film. However, this was only a first step and they needed more dramatic data to advance their research program. At this point, Schön visited his old research lab at Konstanz and took data on the conduction properties of organic crystals. He wanted to demonstrate that these crystals were promising candidates for producing integrated circuits and to show that Bell Labs samples were testing the fundamental limits of plastic materials. At this point, the figures produced by Schön begin to show modifications. Voltages obtained were shifted upwards, results were “smoothed” or peaks “added” in order to provide more impressive results. Schön later stated that “Coming to Bell Labs I learned that figures should be the most important part of publications.” At first, this was apparently a motivation for him to “tweak” his results to obtain more impressive figures.

One of the most important aspects of the Bell Labs program on organic crystals was to discover crystals that had very high mobilities (the ease with which charges move through the system). One of the major disadvantages of plastic compared to silicon is that in general, mobilities of charges in silicon are hundreds to thousands of times larger than mobilities in plastic. If plastic substances could be produced with very high mobilities, then these substances could conceivably be used to produce transistors that could compete with those in silicon. Christian Kloc supplied Schön with organic crystal samples, and the results claimed by Schön seemed to indicate that these crystals were showing much greater mobilities than in the past. The Bell Labs group were claiming to have produced mobilities in plastics at low temperatures that were “thousands of times greater than had ever been measured for organic crystals.” After the investigation of Schön’s research, these claims have now been retracted. However, these stunning results began to be published in the most venerable and prestigious scientific journals, Nature and Science. The journal Nature was first published in 1869 and Science in 1880. Those journals accept very few of the papers that are submitted to them, and they pride themselves on being the journals most frequently approached to publish the most important scientific breakthroughs.

Hendrik Schön was keenly aware of the prestige of these journals. He was also aware that Bell Labs groups were focused on discovering new materials that could be patented and converted into applications that might revolutionize various fields. The pinnacle of such achievements was Bell Labs’ creation of the transistor in 1947, a discovery that created the electronics industry. So Schön queried his colleagues about new devices that might be produced, and he set out to investigate these ideas and publish claims of revolutionary breakthroughs in several areas. Every year at Bell Labs, department managers compiled a list of “stretch goals,” new discoveries that might be accomplished in the next year or so. In 1999, Bertram Batlogg produced a list of such “stretch goals” for his Department of Materials Physics group. One of these stretch goals was to obtain a deeper understanding of organic crystals and their potential to form elements like transistors in integrated circuits. A second was to produce a 2-dimensional electron gas in organic crystals.

Schön was aware of experiments showing that metal oxides could provide a good insulating material to produce high mobilities in crystals. Metal oxides might be much more effective than the Kapton film used earlier by Schön and Batlogg. So Hendrik traveled back to Konstanz, where he used a sputtering machine to deposit Aluminum Oxide layers on organic crystals. Figure II.5 shows a schematic picture of a sputtering machine. A target and substrate are placed inside a vacuum chamber. Argon ions are accelerated in the chamber and strike a target material, knocking atoms out of the target. Those atoms then travel to the substrate where they can produce a thin film atop the substrate.

Figure II.5: A schematic diagram of the sputtering process. An electric field is applied to accelerate Argon ions. that knock atoms off a target material. The atoms strike the substrate and are deposited on the substrate. This produces a thin film on the surface of the substrate.

Schön had used the sputtering device as a graduate student at Konstanz, and he proceeded to lay down a thin film of Aluminum Oxide atop organic crystals. He then brought back these samples to Bell Labs and carried out experiments with them. One of the most striking results, obtained in December 1999, was the observation of the Quantum Hall Effect (QHE) in crystals of pentacene.

Figure II.6 shows the figure by Schön, Kloc and Batlogg showing that they had observed the Quantum Hall Effect. Schön had laid down an aluminum oxide layer on top of pentacene crystals, then cooled the sample down to 1.7 K (i.e., 1.7°C above absolute zero temperature). The ‘signatures’ that the QHE was seen were the oscillations in the magnetoresistance Rxx plotted vs. the reciprocal of the magnetic field, and plateaus in the magnetoresistance Rxy vs. magnetic field.

Figure II.6: A figure purporting to show the Quantum Hall Effect (QHE) in measurements with pentacene crystals. The ‘signatures’ of the QHE are oscillations in the magnetoresistance Rxx, and plateaus in the magnetoresistance Rxy. These are clearly visible in the data shown, which was taken after the sample was cooled to 1.7 Kelvin.

The oscillations and plateaus are clearly visible in the data that was published. This result was a major coup for the Bell Labs group. First, this result was apparent proof that they had managed to produce a two-dimensional (2-D) electron gas using this organic crystal. Second, the observation of the Quantum Hall Effect showed the incredibly precise measurements that Schön had performed. The QHE was known to occur only at very low temperatures, and required exceptional care. These results gained Schön a reputation as a superb experimentalist. Nobel laureate Horst Störmer, who was a professor at Columbia and had an adjunct appointment at Bell Labs, called Schön a “wizard.”

But it should be emphasized that Schön’s research collaborators and his colleagues at Bell Labs never saw his data-taking, and for that matter never saw the pentacene crystal with the aluminum oxide insulating layer. Schön claimed that he had worked all night by himself taking the data, and that immediately after the conclusion of the experiment, he had removed the crystal in order to take it back to Konstanz. Furthermore, no one saw any raw data from the experiment – they saw only the “processed” results in the figures. After this result, no one afterwards took experimental data runs with Schön while he worked with his magnificent crystals (Schön’s explanation was that he worked by himself all night taking data).

The quantum Hall Effect results marked a new phase in Hendrik Schōn’s career. From this point on, he would talk with colleagues about potential new advances in materials physics. Shortly afterward, he would show up with beautiful results that would confirm the hopes and expectations of his collaborators. A typical example was his work with what were called “Buckyballs,” a slang term for Buckminsterfullerene. These were molecules of Carbon-60, a configuration where 60 Carbon atoms would arrange themselves in the form of a soccer ball. The structure of Buckminsterfullerene is shown in Figure II.7. It consists of sixty atoms of Carbon that arrange to form a 3-dimensional structure containing 20 hexagons and 12 pentagons.

Figure II.7: A schematic picture of Carbon-60 or Buckminsterfullerene. In this molecule, 60 carbon atoms form a cage composed of 20 hexagons and 12 pentagons. The shape resembles a soccer ball; it also resembles the geodesic dome structures popularized by Buckminster Fuller, hence the name Buckminsterfullerene.

Buckyballs were first discovered in 1985 by a team from Rice University who used a laser to vaporize carbon from a sample of graphite. Three researchers from that team shared the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for that discovery. Buckyballs have a number of interesting applications, and in fall 1999 Hendrik Schōn had a conversation with UCLA chemist Robert Haddon, who had been able to induce superconductivity in Buckyballs by adding potassium to them. Haddon told Schōn that he had tried and failed to produce superconductivity in pure Buckyballs with no added materials. Christian Kloc at Bell Labs began making crystals of Carbon-60, and Schōn reportedly used these to make field-effect transistors. A couple of months later, Schōn told Haddon that he had observed superconductivity at a temperature of 11 Kelvin. As the temperature is decreased, the resistance of a superconductor will suddenly drop to zero at a critical temperature. The curves that Schōn sent to Haddon showed beautiful results – curves where the resistance dropped precipitously right at the critical temperature for superconductivity.

When researchers from other labs expressed surprise that Schōn was able to succeed where others had failed (and Schōn subsequently claimed to observe superconductivity in crystals of pentacene and tetracene), Batlogg responded that previous researchers had been working with ‘dirty’ samples that had contained impurities. Batlogg claimed that Christian Kloc’s organic crystals were extremely pure (this was correct), and that Hendrik Schōn had been using state-of-the-art sputtering devices that had resulted in an extremely pure and smooth aluminum oxide insulating layer atop Kloc’s crystals. Here, Batlogg was completely wrong – it appears that the sputtering device Schōn was using at Konstanz was old and likely was contaminated with other substances that had been sputtered before the aluminum oxide. However, Batlogg was a distinguished senior figure in the field of condensed matter physics, and his forceful defense of the blockbuster research papers (with his name on them) helped to delay the time when Schōn’s fraud was unmasked. We will expand upon Batlogg’s role in these experiments in section IV of this post.

In July 2000 Schōn, Batlogg and Kloc were awarded the $10,000 annual Industrial Award at the International Conference on the Science and Technology of Metals. Bertram Batlogg gave a plenary address at the meeting in Austria. Participants there expressed amazement that the Bell Labs group had taken crystals that were normally insulators and turned them into conductors. They then converted the crystals into semiconductors and then superconductors. Scientists were extremely impressed that this had apparently all been done using the same substances. In normal practice, chemists would produce certain substances that might be converted into semiconductors, but molecules that exhibited superconductivity were quite rare, and often had to be specially designed. The Bell Labs results suggested that a much greater range of molecules could exhibit superconductivity.

Then in spring 2000, Schōn announced that he had produced a laser using his organic crystal setup. Earlier, Schōn had claimed that his organic crystals with an aluminum oxide gate layer exhibited ambipolarity: that is, he was able to produce both positive and negative moving charges. This was unlike traditional transistors, where in general only negative charges (electrons) or positive charges (holes) travel through any one system. After the claim of ambipolarity, Bell Labs colleagues suggested to Schōn the possibility that the positive and negative moving charges might be made to collide. In this way his devices might emit light of certain frequencies. This idea had some similarities to conventional lasers. Sure enough, in March 2000 Schōn announced that he had produced laser action in his organic crystal system.

This announcement created both great excitement and considerable confusion in the condensed matter community. The apparent discovery of laser behavior suggested that a number of completely new materials might be coaxed to produce laser light. However, this announcement was also very puzzling. In a conventional laser, initially a pulse of light with a specific wavelength is introduced into the system, and then is greatly enhanced by a process of stimulated emission of radiation of the same wavelength. However, Schōn was apparently able to produce a laser effect without introducing the initial beam of light. Furthermore, in order to produce the conventional laser effect, that light was confined in a chamber where it was reflected back and forth many times, until an intense beam of light was released from the chamber. Schōn’s system had no chamber. So, scientists speculated whether perhaps the organic crystals had facets that reflected the light before it was released.

In any case, Schōn continued to announce “breakthrough” results in a torrent of papers. In the year 2000, he submitted a paper every 8 days on average. In June 2000, Schōn authored 4 “breakthrough” papers; another 4 were submitted in July; and 5 more in August of that year. Nature and Science were his “go-to” journals, but he also submitted papers to other journals as well. In May 2001, Schōn collaborated with Bell Labs chemist Zhenan Bao. They claimed to have taken a single layer of organic molecules (rather than an organic crystal), added an aluminum oxide gate, and produced a transistor. Schōn and Bao made two amazing claims. First, they claimed that the molecules arranged themselves into a transistor under the influence of electric fields. Thus, they claimed to have produced a SAMFET, a ‘self-assembling monolayer field-effect transistor.’ This would have marked a major breakthrough in creating new types of circuit elements. Schōn went even further; he began calling this a “single-molecule organic transistor,” which would have been one of the great nanotechnology discoveries that research groups had been seeking.

Reviewers of the Schōn and Bao paper submitted to Nature raised a number of questions. In Schōn’s response he provided the reviewers with additional figures, and he remarked that they had found success with six different organic molecules. Based on Schōn’s somewhat inaccurate claim that he and Bao had constructed a “single-molecule transistor,” this result was included by Science magazine as one of its “Breakthroughs of the Year” for 2000.

III: Schön’s Fraud is Discovered

It is interesting to follow the reaction of scientists to Schōn’s claimed results, particularly those working in this field. Scientists are generally loath to accuse a colleague of fraud. There are generally many possible alternatives to fraudulent behavior. One of these is that a researcher may not have provided enough information for other scientists to attempt to reproduce their results. Certainly, Schōn and collaborators provided very little detailed information as to how they achieved their breakthroughs. Since they were often publishing in Science or Nature, journals that specialize in short articles and have strict limits on the length of articles, the Bell Labs researchers could only provide limited technical information. In most cases, researchers would follow up a paper in Nature with a significantly longer article in a specialized journal that would provide the detailed technical discussions. However, for reasons that are now clear, Schōn was reluctant to write up the technical details, and he preferred instead to release copious “breakthrough” articles, with essentially no ‘follow-up’ technical papers.

Another possible reason that other scientists were unable to replicate Schōn’s dazzling results was that their experimental apparatus was not sufficiently pure. This is the explanation that Bertram Batlogg insisted upon; the Bell Labs organic crystals were known to be of excellent quality, and Batlogg asserted that Schōn’s aluminum sputtering device was extremely ‘clean’ – a statement that later turned out to be false. And some researchers believed that Schōn had exceptional technical skills, which is why he could obtain results that others could not. However, there was also a growing number of condensed matter researchers who became highly skeptical of the Bell Labs results. Although people were initially reluctant to entertain the possibility of fraud, a number of researchers were coming to this conclusion.

One scientist who felt no qualms about raising the issue of fraud was Bob Laughlin. Laughlin, a theorist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1998 for his explanation of the fractional Quantum Hall Effect, interrupted a seminar by Bertram Battlog in 2000, saying “You should be ashamed of showing these plots!” Laughlin complained that the data shown by Batlogg did not contain sufficient information to check if they were correct. One year later, before Schōn’s lies were revealed, Laughlin warned a Stanford colleague who wished to follow up on the Bell Labs work on organic crystals, “Many groups here, in Europe and Japan, have tried unsuccessfully to replicate this result. I am not the only person worried about fraud.” However, Laughlin’s assertions were not shared by many in the condensed matter community – at least, others were loath to make public such sweeping accusations with limited data, although the outspoken Laughlin felt free to make these bold assertions.

As time passed and more and more people failed to reproduce the Bell Labs results, suspicion grew in this community. Berkeley professor Jay Orenstein obtained some of Christian Kloc’s organic crystals and attempted to study their properties. But when he cooled down the crystal to 100 Kelvin, the crystal shattered. Orenstein could not understand how Schōn could cool his crystals coated with aluminum oxide to a few degrees Kelvin, for his superconductivity and quantum Hall Effect measurements. A group at the University of Minnesota trying to replicate the Bell Labs field-effect transistor found that their electron mobilities were only a tiny fraction of those claimed by Schōn, and they found it exceptionally difficult to deposit smooth layers of aluminum oxide onto the crystals. Several other groups also failed to reproduce the beautiful curves published by the Bell Labs team.

However, the Bell Labs fraud began to unravel when others carefully examined the beautiful figures from Schōn’s papers. One of the first was Don Monroe, who had earlier been a colleague in the Bell Labs condensed matter group. Monroe saw some of Schōn’s results on his SAMFET organic-molecule transistors at a seminar, and he was struck by one of the figures. It showed how the conductance, the degree to which an object conducts electricity, varied with the number of molecules on the transistor. The curve looked eerily similar to a perfect Gaussian distribution. When Monroe checked the data supplied by Schōn with the formula for a Gaussian distribution, he found essentially perfect agreement. But experimental data from actual devices do not produce a Gaussian distribution – they invariably show slight deviations from the perfect Gaussian curve. At this point, Monroe began to suspect that the results were fraudulent. He conveyed his suspicions to the Bell Labs management; Monroe told them that from his statistical analysis, he estimated a 90% chance that the data had been “distorted,” and greater than a 50% chance that the distortion was intentional. Monroe recommended that Bell Labs carry out an internal investigation.

Bertram Batlogg had left Bell Labs in summer of 2000 for a professorship at the Swiss Institute for Research in Zūrich. In early 2002, when he got word that Bell Labs had begun an inquiry into Henrik Schōn’s research, he pressured Schōn to demonstrate his proficiency in sputtering aluminum oxide insulating coatings over organic crystal samples. Schōn finally agreed to give a demonstration at the laboratory in Konstanz. Apparently, the demo was a miserable failure. Schōn failed to produce samples that could reproduce any of his claimed results. In addition, observers said that Schōn’s experimental techniques were poor. This was one of the first in a chain of discoveries that unmasked his fraud.

Another major revelation occurred when Prof. Lydia Sohn of Princeton was contacted by two researchers at Bell Labs, Julie Hsu and Lynn Woo. They were interested in whether the process of soft lithography could be used to create electrical junctions in Hendrik Schōn’s SAMFET devices. They began by reading all of Schōn’s papers on organic molecule circuit elements. When they did, they noticed that figures from different papers, that represented extremely different physical situations with different normalizations, were apparently identical. Hsu and Woo knew that instead of being identical, the outputs in Schōn’s papers should have been quite different. When they noticed other apparent duplications of figures, they shared their observations with Prof. Sohn. Sohn then notified a number of her colleagues about the duplications in Schōn’s papers.

Scientists who saw the duplicated files divided into two camps. One group assumed that Schōn had simply made an error, and somehow mixed up data from two experiments. This was in fact Schōn’s response when he was challenged – that he had inadvertently mixed up results from two different experiments. He rapidly came up with a revised figure for one of two papers. However, a second group of scientists were convinced that these duplications represented cut and dried evidence of fraud. They pointed out that the captions on the two papers were radically different – so Schōn was not simply reproducing exactly the same figure in two different papers. They also felt that Schōn’s “revised” figure also contained some very suspicious features. Perhaps the most dogged experimentalist was Paul McEuen at Cornell. McEuen was an expert on “buckyballs,” the molecules that Schōn had claimed to make superconducting. McEuen was angry with Schōn’s explanation, so he combed through all of Schōn’s papers, looking for duplicated figures.

After a short while, McEuen had located six duplications in five of Schōn’s papers. These were cases where the figures were identical but they were presented as results for very different systems, and where the figures had totally different captions. When McEuen contacted his condensed matter colleagues at different institutions, they began a systematic search through Schōn’s papers, looking for duplications. In short order McEuen contacted John Rogers, the current head of the Condensed Matter Group at Bell Labs, and the former group head and Schōn collaborator Bertram Batlogg, to inform them of his suspicions. He also wrote and called Hendrik Schōn with an accusation that Schōn had faked his data. And finally, he contacted the editors at Nature and Science and spelled out his conclusion that the Bell Labs work was fraudulent.

The Bell Labs management appointed an external committee to review the work of Schōn and collaborators. The committee was chaired by Stanford professor Malcolm Beasley, who was a distinguished expert on superconductivity. The committee included two people who had been critical of Schōn’s work. One of these was Don Monroe, who had previously been a colleague of Schōn. Monroe had raised the issue of irregularities in Schōn’s published work, but he had retracted these comments when Schōn sent him “revised” data. The editors from Nature and Science were very concerned about the allegations. The word got out that serious questions had been raised, and on May 23, 2002, the New York Times ran an article regarding “suspicions about Bell Labs research.”

Figure III.1: A 2002 report from Physics World that Bell Labs had appointed a committee to review claims of misconduct by Hendrik Schōn and his research group at Bell Labs.

The Beasley Report:

In May 2002, Bell Labs commissioned the Beasley external committee to investigate possible scientific fraud, or other examples of scientific misconduct. In September 2002, Bell Labs released the 127-page report of the committee. The committee considered 24 allegations of scientific misconduct that involved 25 papers of Schōn and collaborators. On the great majority of these papers were co-authors and Bell Labs colleagues Christian Kloc and Bertram Batlogg. On a few other papers was Bell Labs chemist Zhenan Bao; she worked with Schōn on the papers involving thin layers of organic molecules.

In their investigation, the Beasley Committee interviewed Hendrik Schōn at length. These discussions revealed a very troubling situation. They requested Schōn’s laboratory notebook, but he stated that he did not keep a laboratory notebook. (This alone is already a violation of scientific ethics.) They asked for the raw data files from his computer; Schōn stated that he had deleted the raw data files because his computer had insufficient hard drive space to hold this data. They asked Schōn to provide them with examples of the samples that he had created and used in his experiments. Schōn responded that all of his samples had been damaged or discarded. Although Schōn continued to insist that he had actually measured all of the phenomena in his many papers, he produced essentially no solid evidence that could verify his claims.

The Beasley committee investigated scientific misconduct in three categories:

- Substitution of data: This involved substitution of whole figures, single curves or partial curves in different papers or in the same paper to represent different materials, devices or conditions. The committee investigated 9 possible examples in this category.

- Unrealistic Precision: Precision beyond that expected in a real experiment or requiring unreasonable statistical probability. The committee investigated 9 possible examples in this category.

- Contradictory Physics: Behavior inconsistent with stated device parameters and prevailing physical understanding, so as to suggest possible misrepresentation of data. The committee investigated 6 possible examples in this category.

The Beasley Committee concluded (see Fig. III.2) that Schōn had committed scientific misconduct in 16 of these cases, saying “The evidence that manipulation and misrepresentation of data occurred is compelling.” The committee further concluded that 6 of the remaining 8 allegations were “troubling;” however they felt that these examples “did not provide compelling evidence” of wrongdoing.

Figure III.2: Sept. 2002 New York Times article on the Beasley Report concluding that Hendrik Schōn had committed several instances of fraud in his papers announcing breakthroughs using organic materials as circuit elements.

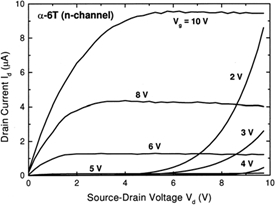

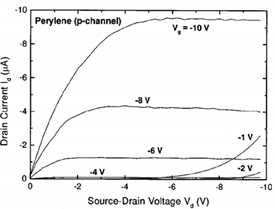

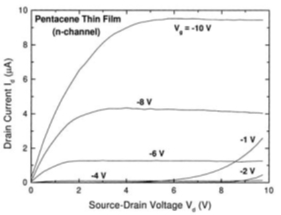

Here are two examples of fraud, out of the 16 fraudulent claims laid out in the Beasley report. The first is an example of “duplication of data.” Figs. III.3a, III.3b and III.3c are from different papers published by Hendrik Schōn and collaborators in 2000 and 2001. The first paper claimed to demonstrate a field-effect transistor that emitted light. Figure III.3a shows the drain current in microamperes vs. the source voltage in Volts from that paper. The curves are shown for several choices of the gate voltage. Figure III.3b shows current vs. voltage for a paper claiming to produce a field-effect transistor created using crystals of perylene. And Fig. III.3c shows current vs. voltage for a paper announcing an “ambipolar” transistor made using crystals of pentacene. The case of perylene was claimed to be one where the charge carriers were “holes” (positive charges in a sea of electrons), rather than electrons as in Figs. III.3a and III.3c. Therefore, the sign of the voltages and the gate voltage are reversed from those in the other two figures.

Figure III.3a: Triode characteristics (drain current vs. source-drain voltage) from a paper by Schōn and collaborators purporting to show transistor behavior in crystals of alpha-sexithiophene.

Figure III.3b: Triode characteristics (drain current vs. source-drain voltage) from a paper by Schōn and collaborators purporting to show transistor behavior in crystals of perylene. Note that the sign of the voltage is opposite of that in Fig. III.3a.

Figure III.3c: Triode characteristics (drain current vs. source-drain voltage) from a paper by Schōn and collaborators purporting to show ambipolar transistor behavior in crystals of pentacene.

The three figures supposedly show currents vs voltage for three quite different crystals, under rather different conditions. However, it was proved that the curves were exactly the same. This is a result that is impossible to believe. To make matters worse, note that although the curves are identical, in going from Fig. III.3a to III.3b, the values of the gate voltages were changed, with 5V in Fig. III.3a going to -4V in Fig. III.3b, 4V to -2V, and 3V to -1V. Hendrik Schōn‘explained’ his result by claiming that a number of different files were stored in the same folder. Thus, he accidentally chose the wrong figures for some of his papers. The Beasley committee did not buy this (especially when the gate voltage labels were changed from one paper to another), and they concluded that “the preponderance of evidence indicates that Hendrik Schōn committed scientific misconduct” in this case.

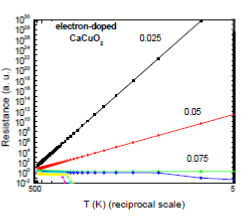

An example of ‘unrealistic precision’ is shown in Figures III.4. These plots show resistance vs. temperature for samples of CaCuO2 for various levels of electron doping. This paper by Schōn and collaborators purported to show superconductivity in organic crystals. Figure III.4a shows resistance vs. temperature curves for various levels of electron doping in the samples. The Beasley committee was able to obtain the data used to produce curves of resistance vs. temperature for higher temperatures where the substance was insulating. Figure III.4b shows the resistance vs. temperature curves for various electron doping levels over 30 orders of magnitude in the resistance; however, the ‘data’ in Schōn’s draft existed over a range of 70 orders of magnitude. The Beasley committee first noted that this was impossible – measuring devices are unable to obtain accurate data for a range greater than about 12 orders of magnitude. Second, Fig. III.4b compares the ‘data’ with curves from a theoretical model due to Arrhenius. The model goes precisely through all data points; one of the signatures scientists look for in determining the credibility of experimental results is whether the data seem too good to be true in comparisons to theory.

Figure III.4a: A plot of resistance vs. temperature for samples of CaCuO2 for various levels of electron doping. This paper by Schōn and collaborators purported to show superconductivity in organic crystals.

Figure III.4b: The Beasley committee obtained the ‘data’ reported by Schōn and collaborators on the insulating side of the superconducting transition. Here, the resistance vs. temperature curve is plotted over 30 orders of magnitude in the resistance. It is compared to a theoretical model by Arrhenius, which goes precisely through all the data points.

When Hendrik Schōn was confronted with these results, he admitted that curves shown in this paper for both the insulating and superconducting phases were generated from theoretical formulae; however, he maintained that he had measured an actual superconducting transition for this material. However, he could not produce any actual data that demonstrated his claim. The Beasley committee noted that Schōn had admitted falsifying the data in these figures; they concluded that this was fraudulent, owing to both the data falsification and the unrealistic precision in the ‘data.’

Immediately following the release of the Beasley Committee report, Bell Labs fired Hendrik Schōn. During the period of the investigation, Schōn produced a number of new “breakthrough” claims, and he attempted to publish them. For a while the journals rejected his new papers, until Bell Labs refused to allow him to submit new papers. Schōn continued to insist that all his “breakthroughs” were real, even though he admitted to “mistakes” in publishing identical figures for very different phenomena. Paul McEuen and others also discovered cases where Schōn had published figures of very different phenomena where the figures were duplicates of those in earlier publications, but had now been reduced by a factor of 2 in a couple of cases, and 5 in another. These examples are also included in the report by the Beasley Committee.

Following the work of the Beasley Committee, we have a more accurate picture of Schōn’s methods in his research. For a short period after he arrived at Bell Labs, Schōn conducted experiments with samples from Christian Kloc and in collaboration with Bertram Batlogg. At this stage, it appears that his major form of misconduct was to “enhance” the figures that he produced. The magnitude of effects was increased, noise was suppressed, and the figures appear to have been manipulated to make them more impressive.

However, after Schōn began “producing” samples by using a sputtering device at the University of Konstanz to lay down layers of aluminum oxide over Kloc’s organic crystals, the situation changed dramatically. Figures were “re-purposed” from earlier experiments to later ones with supposedly completely different materials and conditions – an example was shown in Figs. III.3. “Data” that appeared in his figures was sometimes generated using analytic functions – thus, a curve that looked like a Gaussian distribution might be precisely a Gaussian. An example of this is shown in Figs. III.4. And “noise” in his systems, which should have been different for different experiments, was often identical for several of his publications. This raises the question: did Schōn actually create samples using Kloc’s crystals and then sputtering an insulating layer of aluminum oxide atop the crystals? Did he then make “measurements” of his system and then manipulate his (presumably crummy) results until they produced the beautiful, precise curves that appeared in his publications? Or at some point did he just forego making the samples, and “dry lab” the results, creating them from scratch so that they appeared reasonable? We have been unable to find a definitive answer to that question.

IV: The Case of Bertram Batlogg

The Beasley Report investigating the work of Jan-Hendrik Schön and his collaborators concluded that Schön had engaged in fraud in his discovery claims. The Beasley committee cleared several of Schön’s collaborators, including Christian Kloc and Zhenan Bao, of any significant responsibility or negligence for the misconduct of Schön. The Beasley committee found that Bertram Batlogg also “took appropriate action once explicit concerns had been brought to his attention. To this extent, the Committee concludes that Bertram Batlogg met his responsibilities as a co-author.” However, the Beasley committee “felt the need to question whether Bertram Batlogg, as the distinguished leader of the research, took a sufficiently critical stance with regard to the research in question.” The committee noted that “during the period from 2000 to 2002, many condensed matter physicists, with no specific vested interest in the work in question, were becoming seriously skeptical about the extraordinary rate of publication of spectacular results on extremely difficult material systems.” But after raising these statements, the committee did not state that Batlogg’s conduct deserved further criticism and the Beasley Committee concluded that it “Did not consider itself qualified to make a specific judgment in this case, in the absence of a broader consensus on the nature of the responsibilities of participants in collaborative research endeavors.”

Figure IV.1: Prof. Bertram Batlogg, here shown receiving the 2001 Braunschweig Prize for his role in Bell Labs “breakthroughs” in organic semiconductors, results now known to be fraudulent.

We believe that the Beasley Committee should have strongly criticized Bertram Batlogg’s behavior as the senior leader of this research team and the head of the Department of Materials Physics at Bell Laboratories. Consider the following facts regarding the Bell Labs team’s claims of spectacular results:

- During the period from 1997 to 2002, when the fraudulent behavior of Schön and his collaborators was unmasked, Hendrik Schön was one of the most productive scientists in the field of condensed matter physics. His group at Bell Labs made a number of spectacular claims in the field of organic semiconductors, organic superconductors, and molecular transistors.

- The claims of the Bell Labs group, under the supposed leadership of Bertram Batlogg, were considered among the most important discoveries in condensed matter physics. The work was cited as path-breaking research. It led to Schön and the Bell Labs group receiving numerous awards. In 2000, Schön and colleagues Batlogg and Kloc shared a $10,000 award from the International Conference of Science and Technology of Synthetic Materials. And in 2001, the same researchers received the Braunschweig Award of 100,000 Deutschmarks. In 2000, Science magazine listed the Bell Labs claim of producing a single-molecule transistor as one of its “Breakthroughs of the Year.” In 2002, Schön was awarded the Young Investigator Award from the Materials Research Society. He was also awarded the Otto-Klung-Webersbank Preis. And he was one of the researchers listed in the MIT Tech Review list of Young Innovators. [Note: all of these awards have since been revoked. Following the accusations of fraud at Bell Labs, the University of Konstanz initiated its own review and eventually revoked Schön’s Ph.D. degree, despite the fact that there is no evidence that Schön faked the results of his dissertation research.]

Figure IV.2: The cover of Science magazine announcing the 2000 Breakthrough of the Year. That issue also listed finalists for the ‘Breakthrough’ designation. The Bell Labs work on organic crystal circuit elements was one of the finalists.

- After Schön’s fraud was discovered, 28 of his articles were retracted from scientific journals, and another 8 articles were flagged for “concerns.” Of these articles, Bertram Batlogg was a co-author on 20 of the 28 retracted articles and 4 of the 8 “concern” papers.

- Much of Schön’s work was claimed to result from circuits where he laid down a layer of Aluminum Oxide over organic crystals using sputtering techniques. Schön told his collaborators that he created the samples using a lab at Konstanz University where he had obtained his doctorate. However, we now know that Schön either did not create these samples, or the measurements he published were wildly different from his actual results. When his work was finally questioned, he initially claimed that all of those samples had been damaged or destroyed. However, when he was finally forced to demonstrate his skill at producing these semiconducting samples, he was not only unable to recreate the extraordinary results that he claimed (and that no other groups had been able to reproduce), but his experimental skills turned out to be poor. So after a certain point in time, Bertram Batlogg had put his name on several “breakthrough” papers without seeing any of Schön’s “experimental samples” from Konstanz. In addition, apart from some measurements taken soon after Schön arrived at Bell Labs, Batlogg never participated in any data-taking with these samples, nor had he observed Schön taking data with his samples. For a few years Bertram Batlogg was giving talks on this ‘fantastic’ research all over the world. Colleagues who attended Batlogg’s talks got the distinct impression that the samples used in this research had been fabricated at Bell Labs; whereas Schön reported that the samples had all been produced at the lab in Konstanz where he had obtained his doctorate.

- In addition, when condensed matter physicists finally suggested that Schön’s data was not real, and he was challenged to produce the lab notebooks recording his raw data, Schön admitted that he had not kept any such notebooks! He claimed that his raw results had been taken down by hand and that only the “processed” results existed. Note: the father of one of us (TL) was a research chemist at DuPont. One summer while in high school, TL was employed by the Records Division at DuPont labs. Most of that summer was spent photographing lab notebooks by DuPont scientists. These were used to justify the research behind DuPont’s patents. If an experimental scientist at DuPont could not produce a lab notebook, they would have been in trouble; and if this had occurred over a series of years they would have been fired. However, at Bell Labs Hendrik Schön had apparently been doing some of the finest research in the world, and yet his Division Head Bertram Batlogg had never seen any of his raw data, nor any lab notebooks containing Schön’s unprocessed research results!

- Jan Hendrik Schön was a clever, though not very careful, fraud. He managed to fool his colleagues and supervisors at Bell Labs for several years. For some time, he skillfully deflected requests to see his samples and his lab notebooks. He consulted with colleagues about the scientific conditions in fields where he was supposedly taking data; for the most part, he then produced “results” that agreed with expectations or hopes of the experts, and thus fooled them. So initially, it is no surprise that he fooled Bertram Batlogg as well. However, for Batlogg to continue to add his name to Schön’s research claims, and to share in international acclaim and awards for his non-existent “breakthroughs” for such a long time, seems like dereliction of duty at the very least and, frankly, nothing short of professional dishonesty. Batlogg certainly failed to insist on independent corroboration of Schön’s claims. If you claim a series of “breakthroughs” that could revolutionize your field, you have an obligation to ensure that your results can be duplicated by more than one colleague.

- Bertram Batlogg continues to insist that he bore no responsibility for the many “breakthrough” papers that contained fraudulent results. In fact, he claims that he was the biggest victim of Hendrik Schōn’s fraud! Batlogg told a German journalist, “If I’m a passenger in a car that drives through a red light, then it’s not my fault.” It should be no surprise that Batlogg’s claim is rejected by many in the physics community. Prof. Lydia Sohn responded, “If a young driver has a learner’s permit, then who’s responsible for him? Batlogg was the licensed driver, and Schön was the student driver.” Physicist Arthur Hebard stated “Batlogg signed on. He’s a collaborator, not a casual passenger. He’s been benefitting all along, riding the public wave.” Prof. Douglas Nadelson observed “If my student came to me with earth-shattering data, you wouldn’t be able to pry me out of the lab. I’d be in there turning the knobs myself.”

- In 2002, rocked by the frauds that were uncovered at Bell Labs and with the Berkeley group’s fraudulent claim of having discovered element 118 (covered in Part I of this series), the American Physical Society (APS) revised its ethics guidelines for scientific research. A major point of contention was whether all collaborators in scientific projects should be held responsible for claims made in these papers. Physicists expressed the strong belief that all collaborators in group research should be responsible for claims made in their papers. There was strong support for guidelines indicating that senior scientists involved in work that turned out to be fraudulent or sloppy should bear some responsibility for papers containing their names. And Bertram Batlogg’s behavior in this scandal was certainly a motivating factor in passing these new expanded guidelines for ethical conduct in research.

V: Some Comments on Peer Review:

After the Ninov and Schön fraud scandals, a number of people leveled sharp criticism of the peer review system. One common complaint was, “Why didn’t the peer review process discover that the Bell Labs results were fraudulent? After all, that is one of the functions of the peer review process.” Sorry, but that is not the case. Although it would have been possible for a reviewer to spot the phony data in Schön’s figures, one should not expect reviewers of papers to spot well-disguised fraudulent data. Consider the published papers from the Bell Labs groups. These were considered to be some of the most path-breaking achievements in physics. Groups around the world unsuccessfully attempted to replicate the Bell Labs results, in order to further extend these findings. Scientists would have pored over the Bell Labs papers, in attempts to achieve the same results as Schön and collaborators. Until the Bell Labs researchers Hsu and Woo discovered that Schön had used identical figures in several of his papers, no other researchers had noticed this. In our opinion, expecting peer reviewers to spot the duplication of figures from different papers than the one they are reviewing would be asking too much.

In this case, a common complaint of condensed matter scientists was that the Bell Labs papers gave insufficient information for the experiments to be repeated. For a while Schön exploited features of top journals such as Nature and Science. Because these journals are designed to highlight new breakthroughs, they publish only very short articles. The page limitations of these journals thus preclude long technical descriptions of research that has been performed. Scientists have reacted to these limitations by creating different specialized journals. While Nature and Science don’t provide enough space to accommodate long technical discussions, there are other scientific journals that tend to publish just such technical material. In the case of Schön and collaborators, a logical step would have been to write separate papers that gave full descriptions of the techniques in their experiments, and to submit those papers to specialized technical journals.

Hendrik Schön exploited this system to his benefit. When reviewers of some of his papers in Nature and Science requested more detailed technical information, he often provided them with additional technical “data.” Like his papers, the technical data was also fraudulent; but at the same time, it was convincing to the reviewers (Schön spent considerable time combing the literature, so he knew what scientists were anticipating). The reviewers were generally satisfied with the fraudulent answers provided by Schön. Eventually, as more and more groups failed to replicate Schön’s claims, the Bell Labs staff put pressure on Schön to publish more technical papers that would answer questions raised by these groups. Schön apparently agreed to honor the Bell Labs requests, but almost never followed through with the promised technical papers.

Schön tended to respond to the criticisms and queries from peer reviewers by providing additional material (generally fabricated) to answer some of their queries. However, he simply did not respond to some of the questions from reviewers. In some cases, Schön’s responses were relayed from the journal editors to the reviewers. In some cases the reviewers recommended that the paper be published, despite the fact that not all of their criticisms had been addressed. In other cases, the journal editors read Schön’s response, and decided that the paper should be published without checking back with the reviewer. In this sense, the journal editors should bear some blame for publishing these papers. However, one should remember that Schön was quite clever. He managed to hide his fraud for a couple of years before it finally caught up to him.

Nobel Laureate Philip Anderson accused the top journals of complicity in this fraud. He argued that these journals “decide for themselves what is good science – or good-selling science.” Their decisions “encourage people to push into print with shoddy results.” We don’t fully agree with Anderson’s arguments. When a paper is submitted to Nature, the editors reject some papers out of hand and send others out to reviewers. However, unless the reviewers respond that the paper in question is path-breaking, the paper will not be published in that journal. We are not sure why this proves that Nature “decides for themselves” what should and should not be published, and we disagree that decisions by prestigious journals “encourage” people to submit shoddy or fraudulent material. However, there is a case to be made that when treating brief reports of sufficiently spectacular results in a field as competitive as condensed matter physics, the journals do not insist sufficiently that all questions and doubts raised by reviewers be addressed to the reviewers’ satisfaction even if it entails delay in publication. Thus, some prominent journals fail to live up to the famous standard voiced by Carl Sagan: “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

VI: Summary

During the five years that Jan Hendrik Schön was employed at Bell Labs, he was one of the most prolific scientists in the world of condensed matter physics. He published dozens of papers on topics at the cutting edge of his field. His papers seemed to indicate that organic molecules could be fabricated as circuit elements for computer chips. If true, that would have indicated that manufacturers of computers could replace integrated circuits based on silicon substrates, and instead use much smaller organic molecules. In addition, the Bell Labs group that included Schön claimed to have used organic molecules to make breakthroughs in the areas of superconductivity and laser light.

The Bell Labs group tended to write short ‘breakthrough’ papers that were published in the most prestigious journals, particularly Nature and Science. Their papers made the Bell Labs group, and particularly Hendrik Schön, famous. He and his major collaborators, the condensed matter group leader Bertram Batlogg and Christian Kloc who produced organic crystals for the group’s research, won major international awards for their breakthroughs. At the same time, the group’s publications proved rather frustrating to condensed matter physicists who were attempting to reproduce the Bell Labs results. The strict limits that Nature and Science imposed on their papers meant that the Bell Labs papers were short on technical details that would allow others to replicate these ‘breakthroughs.’ Over a period of about 18 months, several research groups failed to obtain anything like the results claimed by Schön and his collaborators.

As more and more groups were unable to reproduce the striking Bell Labs results, other researchers began to adopt different theories as to why attempts at replication were failing. The leader of the Bell Labs group, Bertram Batlogg, was a distinguished researcher who threw all of his support behind Schön (Batlogg also added his name to most of Schön’s publications). Batlogg maintained that Hendrik Schön was an extraordinary experimental physicist; in fact, a Nobel Laureate in Physics had called Schön a “wizard.” Batlogg also claimed that the Bell Labs group was able to obtain their fantastic results because the organic crystals grown by Christian Kloc were technically superior; Batlogg also maintained that the sputtering device used by Schön to deposit layers of aluminum oxide on Kloc’s crystals was of exceptional quality, even though Batlogg apparently never observed any of these coated crystals. The sputtering device, coupled with Schön’s supposed experimental brilliance, were claimed to be major reasons for the unparalleled success of the Bell Labs group.

Another group of scientists maintained that they did not understand the technical details of the Bell Labs research. These researchers talked with the Bell Labs experimentalists and invited them to visit their labs in hopes that they could reproduce the Bell Labs results. The fraud was not discovered for several months, in part because Hendrik Schön seemed very helpful. Schön appeared to be modest and friendly. He offered suggestions to these researchers and provided them with unpublished results to help answer their questions. As it happened, the unpublished ‘data’ was itself fraudulent, but it kept these groups from realizing that the Bell Labs ‘breakthroughs’ were phony.

A third group of scientists began to have deep suspicions regarding the Bell Labs claims. Their own results suggested that the Bell Labs results could not be true. They were also suspicious because in a few cases when his claims were challenged, Schön would change some of the technical ‘data’ that he shared with others. For example, in one case Schön reported that he had taken a series of data in steps of 0.001 Volt. It was pointed out that it would have taken almost 20 years to record that many data points; Schön then reported that he had made a mistake, he had taken data in steps of 1 Volt. In a few cases, Schön’s claims appeared to be better than was theoretically possible. However, physicists were loath to make accusations of fraud; in part because the researchers’ reputations would suffer greatly if they made public accusations of fraud that turned out to be false.

From 2000 through early 2002, Hendrik Schön continued to be one of the most prolific scientists in condensed matter physics. He published ‘breakthrough’ papers in physics at an astonishing rate – in one year he submitted a paper every 8 days. But everything changed in spring of 2002, when a couple of scientists at Bell Labs discovered that Schön had published identical figures in studies that were undertaken in very different circumstances. Once this “data falsification” was discovered, scientists combed the Bell Labs papers, looking for unsupported claims. In particular, condensed matter physicist Paul McEuen of Cornell University discovered many examples appearing to show scientific misconduct.

When he was first confronted with these allegations, Hendrik Schön attempted to recover. He admitted using identical figures in different papers but claimed this was simply a mistake. He admitted “smoothing” certain curves so that the crucial details stood out more sharply. However, as he was pressed further, Schön’s explanations sounded less and less convincing. One of his claims was that every one of his samples of organic crystals with an aluminum oxide insulating layer had been either damaged or returned to the University of Konstanz. Eventually, Schön was forced to give a public demonstration of his sputtering technique, and to produce new samples that could reproduce the Bell Labs results. Not only could he not produce any samples with characteristics similar to those the group claimed, but observers claimed that Schön, the “wizard” of Bell Labs, showed poor experimental skills!

At this point, Bell Labs management appointed an external committee chaired by Stanford University physicist Malcolm Beasley, to investigate the Bell Labs group and their publications. The Beasley report, issued in Sept. 2002, found that Hendrik Schön had committed numerous acts of scientific misconduct. Amazingly, they discovered that not only could Schön not produce any existing samples with which he had undertaken his research, but he had kept no lab notebooks, so there were no records of the ‘results’ he had obtained! The committee found several examples where identical figures had been published in papers describing radically different systems. They also found cases where “data” had been generated using analytic functions, rather than been measured. And finally, they found instances where Schön’s results contradicted known properties of physical systems.

We note that the case of the Bell Labs fraud agrees well with claims that the scientific method is self-correcting. Here, the Bell Labs group claimed a number of ‘breakthroughs’ that if true would revolutionize the field. Many groups attempted to replicate these results, and all failed to obtain the same results as Bell Labs. These scientists communicated their results to their colleagues and to the Bell Labs researchers. They also scrutinized the Bell Labs papers in an attempt to understand how these results were obtained. Within about 18 months of the first publication, researchers had discovered evidence of scientific misconduct. A group of expert scientists was commissioned to investigate these claims, and they produced a report that clearly demonstrated numerous instances of scientific fraud.

The results claimed by Schön and collaborators were so remarkable that many scientists worked on reproducing them. In some cases, graduate students spent many frustrating months in fruitless efforts to reproduce the Bell Labs findings. Some of them subsequently transferred to other research groups, and a few left physics altogether. Some postdoctoral researchers who worked on these findings found that working in this area set back their careers. A postdoc generally has 2-3 years to establish their publication record, and a year wasted in failed attempts to reproduce this data could be a significant handicap for them. The same is true of research groups that tried and failed to achieve the spectacular “results” from the Bell Labs scientists.

However, in a few cases dogged experimentalists had made changes to their systems after failing to reproduce the Bell Labs results, and they eventually were successful in producing some of the effects that Schön and collaborators had claimed. In 2003, researchers at the Delft University of technology reported the observation of ambipolarity (movement of both positive and negative charges) in thin films of pentacene. And in 2006, a group at Cambridge University and another group at the University of California, Santa Barbara were successful in getting an organic field-effect transistor to emit light. These cases do not validate the claims from the Bell Labs group (the results obtained look rather different from those published by the Bell Labs researchers). But they show how resourceful scientists can alter their research programs to succeed, even after initial failures.

And what about Hendrik Schön? Following his firing in disgrace after the publication of the Beasley Committee report and the revocation of his Ph.D. degree, Schön has apparently taken a job in a German technology company. It is unthinkable that a research university would ever hire him for a position similar to the one he held at Bell Labs. Schön’s collaborators also moved on after the debacle at Bell Labs. We mentioned that Bertram Batlogg had left Bell Labs in the middle of 2000 to take up a position at ETH in Zůrich. Batlogg continued his research, but with a significantly smaller research group and a reputation that was battered by his actions in supervising Schön. Christian Kloc, who had produced the organic crystals used in the Bell Labs research, took a faculty position at a university in Singapore. The chemist Zhenan Bao, who had produced thin films of organic molecules, became an expert in the field of organic circuit elements. In 2003 she was honored as one of the TR100 young innovators by Technology Review, and in 2004 she took up a faculty position at Stanford University.

The Schön fraud at Bell Labs led to the adoption of new ethics rules by the American Institute of Physics. These clarified that all members of a research collaboration must take some degree of responsibility that the work they publish is accurate and honest. We hope that, after the Schön case outlined here and the Ninov case in Part I of this series, future scientists will have a more heightened understanding of the necessity to have research results (particularly ones that are touted as ‘path-breaking’) checked and duplicated by more than one person. And we hope that senior scientists who insist on adding their names to every piece of work emanating from their research group will take more responsibility for ensuring that the work is accurate.

Source Material:

Wikipedia, Optical Tweezers https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Optical_tweezers

Wikipedia, Scanning Tunneling Microscope https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scanning_tunneling_microscope

Wikipedia, Atomic Force Microscopy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atomic_force_microscopy

Richard Feynman, Plenty of Room at the Bottom, https://web.pa.msu.edu/people/yang/RFeynman_plentySpace.pdf

Wikipedia, Moore’s Law https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moore%27s_law

Wikipedia, Schōn Scandal https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sch%C3%B6n_scandal

Wikipedia, Bertram Batlogg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bertram_Batlogg

Wikipedia, Transistor https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transistor

Eugenie Samuel Reich, Plastic Fantastic: How the Biggest Fraud in Physics Shook the Scientific World, St. Martin’s Griffin, 2010 https://www.amazon.com/Plastic-Fantastic-Biggest-Physics-Scientific/dp/0230623840

Wikipedia, Quantum Hall Effect https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_Hall_effect

Wikipedia, Buckminsterfullerene https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buckminsterfullerene

Wikipedia, Laser https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laser

Dennis Overbye, After Two Scandals, Physics Group Expands Ethics Guidelines, New York Times, Nov. 19, 2002 https://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/19/science/after-two-scandals-physics-group-expands-ethics-guidelines.html

David Rotman, We’re Not Prepared For the End of Moore’s Law, MIT Technology Review, Feb. 24, 2020 https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/02/24/905789/were-not-prepared-for-the-end-of-moores-law/

J.H. Schön and B. Batlogg, Modeling of the Temperature Dependence on the Field-Effect Mobility in Thin Film Devices of Conjugated Oligomers, Applied Physics Letters 74, 260 (1999) https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apl/article/74/2/260/86088/Modeling-of-the-temperature-dependence-of-the

Kenneth Chang, Similar Graphs Raised Suspicions on Bell Labs Research, New York Times May 23, 2002 https://www.nytimes.com/2002/05/23/us/similar-graphs-raised-suspicions-on-bell-labs-research.html

Leonard Cassuto, Big Trouble in the World of Big Physics? The Guardian, Sept. 18, 2002 https://www.theguardian.com/education/2002/sep/18/science.highereducation

Peter Gwynne, Research Misconduct Claim Hits Bell Labs, Physics World 15, 6 (2002). https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2058-7058/15/6/4/meta

Lucent Technologies, Report of the Investigation Committee on the Possibility of Scientific Misconduct in the Work of Hendrik Schön and Coauthors, Sept. 2002 https://media-bell-labs-com.s3.amazonaws.com/pages/20170403_1709/misconduct-revew-report-lucent.pdf

J.H. Schön, A. Dodabalapur, Ch. Kloc and B. Batlogg, A Light-Emitting Field-Effect Transistor, Science 290, 963 (2000) https://www.jstor.org/stable/3078294

J.H. Schön, Ch. Kloc and B. Batlogg, Perylene: A Promising Organic Field-Effect Transistor Material, Appl. Phys. Letters 77, 3776 (2000) https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apl/article/77/23/3776/113721/Perylene-A-promising-organic-field-effect

J.H. Schön, Ch. Kloc and B. Batlogg, Ambipolar Organic Devices for Complementary Logic, Synthetic Materials 122, 195 (2001) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0379677900013539

J.H. Schön, M. Dorget, F.C. Beuran, X.Z. Zu, E. Arushanov, C.C. Cavellin and M. Lagues, Superconductivity in CaCuO2 as a Result of Field-Effect Doping, Nature 414, 434 (2001) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11719801/

E.J. Meijer et al., Solution-Processed Ambipolar Organic Field-Effect Transistors and Inverters, Nature Materials 2, 678 (2003) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14502272/

J. Zaumseil, R.H. Friend and H. Sirringhaus, Spatial Control of the Recombination Zone in an Ambipolar Light-Emitting Organic Transistor, Nature Materials 5, 69 (2006) https://www.nature.com/articles/nmat1537

J.S. Swensen, C. Soci and A.J. Heeger, Light Emission From an Ambipolar Semiconducting Polymer Field-Effect Transistor, Applied Physics Letters 87, 253511 (2006) https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apl/article/87/25/253511/330626/Light-emission-from-an-ambipolar-semiconducting

D. Lorenz et al., Bericht ůber die Průfund Wissinschaftlichen Fehlverhaltens von Herrn Dr. Jan Hendrik Schön, University of Konstanz http://www.uni-konstanz.de/struktur/schoen/html

David Goodstein, On Fact and Fraud: Cautionary Tales from the Front Lines of Science, by David Goodstein https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691139661/on-fact-and-fraud

William Broad and Nicholas Wade, Betrayers of the Truth: Fraud and Deceit in the Halls of Science, Simon & Schuster, 1983 https://www.amazon.com/Betrayers-Truth-Fraud-Deceit-Science/dp/0712602437