November 20, 2023

Overall Introduction:

In 2000, one of us (TL) taught a course on physics that included a section on scientific ethics. In this course we studied various examples of scientific fraud. At that time, most frauds were occurring in the bioscience field, and there were very few recent cases of fraud among physicists. We remarked on this and made some speculations as to why this was the case. We may have been a bit smug about the fact that cases of fraud were rare in our own discipline. However, just a few years later the field of physics was rocked by a few highly publicized cases of fraud. This has made us re-consider cases of apparent fraud or deliberate deception in instances where major discoveries were claimed.

Our reliance on scientific research and reproducible data in our posts on this site is not meant to imply that scientists are always honest or always careful. But the scientific method is self-correcting. Headline-grabbing results that appear inconsistent, either internally or with earlier work or with common sense, or too “perfect” (in a technical way), are typically subjected to rapid attempts to replicate the results or unveil flawed assumptions, techniques, or analyses in either the new or older research. Incorrect experiments and conclusions are usually ferreted out in relatively short order. Sometimes the culprit is scientific “sloppiness” or even incompetence, but occasionally it is outright fraud. While we have dealt glancingly with scientific fraud in some previous posts (e.g., in the alleged connection between vaccinations and autism), we are now devoting a series of posts to instances of fraud in our own field of physics. This is the first of these posts, covering an alleged discovery of a new superheavy element.

Section I: The Search for New Heavy Elements:

There are two major forces involved in the composition of atomic nuclei. The first is the strong nuclear force. It attracts protons and neutrons (collectively called nucleons) into a very small bound state, the atomic nucleus. However, the strong nuclear force acts only when nucleons are very close together, so close that they are almost touching one another. Since protons have positive electric charge, nuclei are also subject to the Coulomb electric repulsion between protons. This force increases rapidly as the distance between protons decreases; furthermore, the Coulomb force is long-ranged in contrast to the strong nuclear force. As nuclei gain more and more nucleons, the radius of the nucleus increases. For heavier atomic nuclei, nucleons on opposite sides of the nucleus become sufficiently separated from each other that they no longer experience the attraction from the strong nuclear force between them.

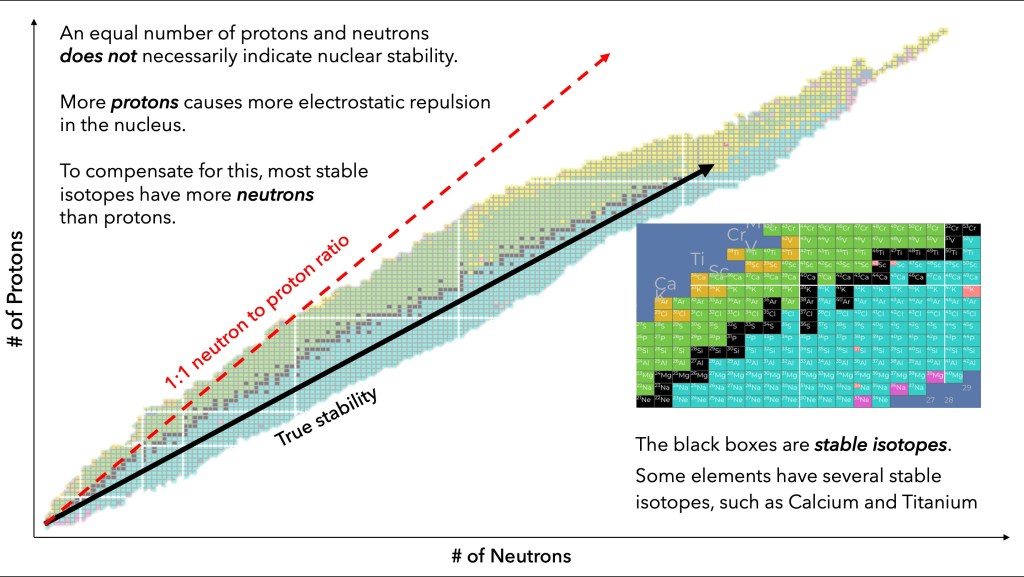

The first manifestation of this competition between attractive and repulsive forces is that as the size of the nucleus increases, heavier nuclei tend to accumulate more neutrons than protons (since neutrons don’t experience any Coulomb repulsion). We will describe nuclei by their atomic number Z, the number of protons in the nucleus, and A the atomic weight that represents the total number of nucleons; for a nucleus containing 8 protons and 8 neutrons we will use the nomenclature 16O8, where the atomic number of oxygen (chemical symbol O) is Z = 8 and the atomic weight is A = 16. Most elements have a number of atomic nuclei that can exist with different numbers of neutrons; this leads to different isotopes of the same element. For example, for carbon although the most common isotope has 12 nucleons (6 protons and 6 neutrons), isotopes Carbon-13 and Carbon-14 also exist. While the dominant isotope for oxygen has 8 protons and 8 neutrons, the most common isotope of gold has 79 protons and 118 neutrons. Figure I.1 shows the distribution of stable nuclides (a nuclide is a nucleus characterized by its atomic number Z, the number of neutrons N and the atomic weight A = N + Z) as a function of the number of neutrons on the horizontal axis and the number of protons on the vertical axis. The stable isotopes are denoted by black boxes while the shaded boxes represent radioactive isotopes that have been discovered; the dashed line is the line with N = Z. As the number of protons increases, the stable nuclei have a larger and larger neutron excess.

Figure I.1: the number of protons Z (vertical axis) vs. the number of neutrons N (horizontal axis) for stable nuclei (represented by the black boxes, surrounded by shaded regions representing radioactive isotopes that have been discovered). The dashed line represents the line N = Z. As the number of protons increases, the number of neutrons N in stable isotopes becomes progressively larger than Z, due to the repulsive Coulomb force between protons.

Even with the addition of progressively more neutrons, when nuclei become sufficiently massive, they become unstable. If we add more and more neutrons, the resulting nucleus will eventually fission into nuclei with smaller A. The heaviest long-lived chemical element found naturally on Earth is uranium; its most common isotope has Z = 92 protons and A = 238, and Uranium-238 has a half-life of 4.5 billion years. We can produce nuclei that have more than 92 protons, but they are unstable and will eventually decay to lighter nuclei.

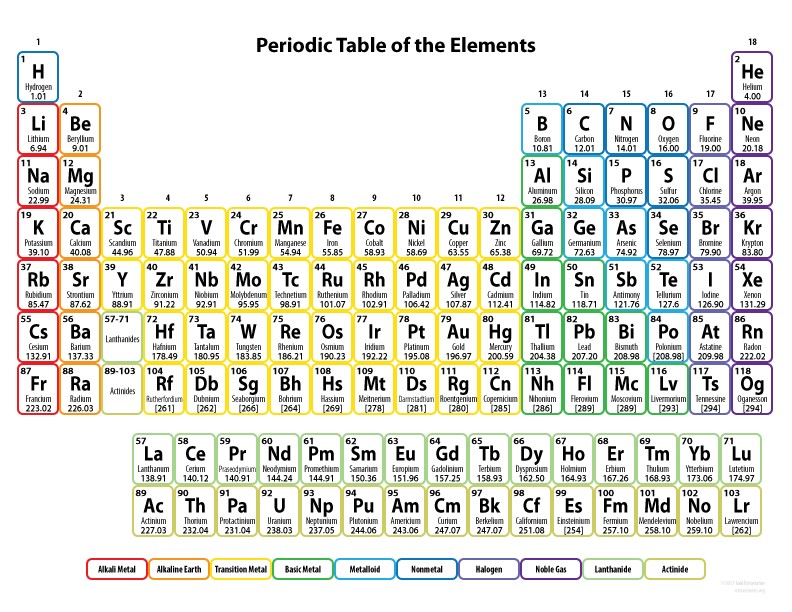

The elements are arranged in the Periodic Table of the Elements, shown in Figure I.2. This table was first compiled in 1869 by the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev. He arranged the elements in rows and columns. Elements in the same column have very similar chemical properties, and the rows are arranged in increasing atomic number Z. We now understand that the chemical properties of elements are determined by the arrangement of electrons in the neutral atom, where the number of electrons is the same as the number of protons in the atomic nucleus. The electrons arrange themselves in shells around the atomic nucleus. (In Quantum Mechanics, the shells represent distinct energy states, but can no longer be thought of as well-defined rings around the nucleus, as is suggested by the term ‘shell.’) Once one shell is filled, electrons begin to populate the next shell. The right-hand column in the periodic table (column 18) represents a closed shell of electrons. The elements in this column form the noble gases. Elements with closed shells of electrons seldom take part in chemical reactions. Elements on the left-hand column of the periodic table (column 1) all have one electron outside a closed electron shell. In chemical reactions, those elements tend to give up one electron, which leaves the ion with one missing outermost electron and a closed shell of the remaining electrons. In contrast, elements in row 17 tend to take on one electron in chemical reactions; again, the resulting configuration with one additional electron is a closed shell of electrons.

Figure I.I: The periodic table of the elements. The original table was produced by Dmitri Mendeleev in 1869. He took all known elements at that time and arranged them in rows and columns. All elements in the same column have similar chemical properties. The current chart contains many heavy elements unknown to Mendeleev.

Current tables of the elements have two additional rows of 15 elements that occur at the bottom of the periodic table. Each of the elements in the first row corresponds to filling electron states in a (4f) shell that can hold up to 14 electrons. In the periodic table itself, the third column in the sixth row of elements is labeled “Lanthanides – 57 to 71.” This place marker represents the 15 elements that make up the “Lanthanide” elements, with atomic number Z from 57 to 71. All lanthanide elements have very similar chemical properties. They are called “rare earths,” which is a misnomer because many of these elements are neither “rare,” nor are they “earths.” However, because their chemical properties are nearly identical, individual elements in the lanthanide series are difficult to separate from the other lanthanide elements.

Likewise, the 15 elements in the bottom row of the periodic table are called the “actinide” elements. Each of these elements corresponds to filling the 5f electron shell, which again can hold up to 14 electrons, and they make up elements with Z = 89 to 103. Glenn Seaborg first observed that all of these elements have very similar chemical properties and it was his suggestion to refer to these collectively as the “actinide elements.” In most renderings of the periodic table of Fig. I.2, the lanthanide and actinide elements are separated out from the rest of the periodic table as separate rows of 15 elements.

The Manhattan Project from June 1942 to August 1947 involved constructing the atomic bombs that were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. That project involved extensive research on uranium (Z=92) and plutonium (Z=94). A detailed set of references to papers claiming discoveries of new elements beyond Uranium can be found in the book From Transuranic to Superheavy Elements, by Helge Kragh. In 1940, McMillan and Abelson concluded that they had detected element 93, from β-decay of Uranium-239, where β-decay is the emission of an electron (called β– because it has a negative charge), or β+ for emission of a positron; the new element was given the name Neptunium (Np). This began a systematic search for heavier unstable elements. A group led by Seaborg observed element 94 produced from β-decay of Neptunium-238; this element was given the name Plutonium (Pu). It was soon discovered that Plutonium-239 fissioned, and this property became a key component of the atomic bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki.

Seaborg and Ghiorso moved to Chicago in the early 1940s to join researchers there in the Manhattan Project, and they continued their pioneering work in heavy element discovery. In 1944 they discovered element 95 (Americium, Am) from β-decay of Plutonium-241, and element 96 (Curium, Cm) by bombarding Plutonium-239 with alpha particles (an alpha particle is the nucleus of Helium-4). Seaborg proposed labeling the elements with atomic numbers 89 – 103 as the “actinide series” after noting that Americium and Curium had nearly identical chemical properties. After the end of World War II, Seaborg returned to his former position at the University of California in Berkeley and continued his work on heavy elements. In 1950, Seaborg’s group announced the discovery of elements 97 (Berkelium, Bk) and 98 (Californium, Cf). Berkelium-243 was produced by bombarding Americium-243 with alpha particles, and Californium-245 was produced by bombarding Curium-242 with alpha particles. For his “discoveries in the chemistry of the transuranium elements” Seaborg was awarded the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Section II: The ‘Transfermium Wars’

In the 1970s, there arose three groups that were active in searching for new elements. We have already described the first of these, the Berkeley group that almost single-handedly discovered elements 95 through 103. The exception to this was the two elements Einsteinium (Es, Z = 99) and Fermium (Fm, Z= 100). These two elements were observed in the aftermath of the first test of the Hydrogen bomb in the U.S. Marshall Islands in November 1952. When Albert Ghiorso and collaborators examined the reaction data following the H-bomb explosion, they found evidence for a new element with Z = 99. In the H-bomb, an initial fission nuclear reaction produces a shock wave that compresses heavy isotopes of hydrogen until they fuse and release a tremendous amount of energy. Element 99 had been formed by Uranium-238 absorbing a series of neutrons from the myriad neutrons released in the explosion and subsequently decaying by a string of six β– decays to produce Californium-253 (Cf). The Californium subsequently emitted one further electron through β– decay, leaving an ion of element 99, which was eventually named Einsteinium (Es). The reactions proceeded as

238U92 + 15n → 253Cf98 + 6β– ,

253Cf98 → 253Es99 + β– (1)

(In Eq. (1), we ignore the neutrinos also emitted in the β– -decays.) Element 100, given the name Fermium, was also discovered in the radioactive material resulting from the H-bomb explosion.

However, in the 1960s a rival group began its own program of searches for new heavy elements. This group was located in the Soviet scientific laboratory at Dubna, roughly 100 km north of Moscow. Its initial leader was Gregory Flerov and he was later succeeded as group leader by Yuri Oganessian. In 1964, the Dubna group reported that they had discovered element 104, which would be the first beyond the actinides and might be classified as “superheavy.” In this experiment, a beam of Neon-22 ions bombarded a Plutonium-242 target. The Dubna group observed spontaneous fission of the ion resulting from the fusion of the beam and target ions. However, the Dubna group was not able to determine either the atomic mass A of the resulting nucleus, nor were they able to determine the half-life of the ion with Z = 104.

In 1969 a team of Berkeley researchers led by Albert Ghiorso launched a discovery claim on the basis of observation of element 104, when they used a beam of Carbon-12 ions to bombard a target of Californium-249. (Although plutonium and californium are radioactive, the isotopes used in these experiments, once produced in the laboratory, are sufficiently long-lived to be used as targets for further bombardment.) The resulting reactions were

12C6 + 249Cf98 → 257Rf104 + 4n,

257Rf104 → 253No102 + 4He2 (2)

In Eq. (2), the first line represents the fusion of Carbon with Californium and the following line shows the decay of element 104 (eventually named Rutherfordium, Rf) to element 102 (Nobelium, No) plus an alpha particle. The Berkeley group observed both the formation of Rutherfordium and its alpha-particle decay. They repeated their experiment with a Carbon-13 projectile, and in that case they observed an ion of Rutherfordium-259.

The controversy over discovery credit for element 104 raised an interesting philosophical issue over “What constitutes discovery of an element?” Remember that in this case, the “element” that is discovered could have a half-life much smaller than one second. In fact, there is general agreement among the scientific community that a heavy ion with a half-life smaller than 10-14 seconds cannot be called an ‘element;’ this is based on the argument that it takes roughly this long for a charged ion to accumulate an electron cloud and form an atom. But the Dubna and Berkeley researchers took very different approaches to defining discovery of an element. The Dubna group argued that the discovery of a superheavy element could be claimed even if the atomic mass A and decay half-life were not determined. The Berkeley group insisted that one could not claim discovery of an element without “definitive” information about the state – and this included identifying both the atomic mass and the half-life.

A similar controversy arose over discovery of element 105. In 1968, scientists at Dubna announced discovery of element 105 based on fusion arising from Neon-22 ions bombarding an Americium-243 target. They repeated their experiment in 1970. But in 1970, the Berkeley group claimed to have observed element 105 in an experiment where Nitrogen-15 ions bombarded a Californium-249 target. This intense competition between the Dubna and Berkeley groups reflected the nationalism of the two teams of researchers. There was much prestige in the discovery of a new heavy element, and the arguments over discovery primacy reflected the “Cold War” political atmosphere during this period. In addition, the discovery claims involved observation of a tiny number of atoms of the heavy element. Fusion of two ions occurs extremely rarely. The researchers combed through data involving an exceptionally large number of reactions in order to isolate a few examples of complete fusion of the ions.

Coupled to the disagreements over discovery rights for new elements was the naming of the new heavy elements. When they claimed discovery of a new element, a research group would typically propose a name for that element. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) had a Commission on Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (CNIC). This body was supposed to ratify names for these heavy elements, as well as names for any new inorganic compounds. The CNIC took the view that they should determine the names for these new elements; however, both the American and Soviet superheavy element teams tended to disregard the CNIC suggestions. So, for example, element 102, Nobelium, was also proposed to be called Joliotium by a group at the GSI laboratory in Darmstadt, West Germany (GSI = Gesellschaft fūr Schulungs und Informationsdienstleinstungen) and Flerovium by the Dubna group; and element 105, Dubnium, was proposed as Kurchatovium by the Dubna group and Joliotium by an IUPAC review group.

Discovery and Naming of Element 106:

The controversy among the major superheavy element research teams (at Berkeley and Dubna, now joined by a team at GSI) continued with element 106. In 1974 a Dubna team led by Flerov and Oganessian claimed the production of element 106 by using a beam of Chromium-54 ions to bombard a Lead-208 target. They claimed observation of spontaneous fission from an ion of element 106. (Since fission usually results in the production of multiple fragments, not all of which may be detected in an experiment, it can be difficult to reconstruct the atomic charge of the fissioning nucleus). Shortly after this, the Berkeley group claimed to observe this element in the following experiment:

18O8 + 249Cf98 → 263Sg106 + 4n,

263Sg106 → 259Rf104 + 4He2 (3)

In Eq. (3) we have used Seaborgium (Sg), the eventual name of element 106, for the ion produced in this reaction. The Berkeley group also observed the subsequent alpha-particle decay of Rutherfordium-259. In 1984, experiments at Dubna showed that their 1974 claimed identification of element 106 was incorrect. This retraction gave the Berkeley group precedence in the discovery claim. However, the naming of the element created a great deal of controversy. The Dubna and Berkeley groups met in 1994 (after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and when Cold War tensions had abated) and came to general agreement that the Berkeley group had precedence in the discovery of this element. Thus, it was highly surprising that the CNIC committee proposed the name “Rutherfordium” for element 106 (it had not yet been formally assigned to element 104), dismissing the Berkeley choice of “Seaborgium,” after their long-time heavy element group leader.

There arose heated arguments over whether a new element could be named for a living figure. People who spoke against naming the element for a living scientist claimed that this had never before been done. However, this argument was weakened by the fact that both element names Einsteinium and Fermium had been submitted while those scientists (Albert Einstein and Enrico Fermi) were still alive – however, both scientists had passed away before the names were officially adopted. The controversy raged for some time; however, eventually the name Seaborgium was accepted for element 106.

The ”Island of Stability”:

The search for new superheavy elements was given new impetus by suggestions that there might exist a set of isotopes of superheavy elements with very long lifetimes compared to other isotopes in this region. Around 1950, researchers Maria Goeppert Mayer and Hans Jensen independently demonstrated that atomic nuclei have a shell structure, analogous to the shell structure of electrons in atoms. The numbers of nucleons that correspond to a closed shell of neutrons or protons are called “magic numbers.” For neutrons, the first seven magic numbers are 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82 and 126. Protons share the first 6 magic numbers as for neutrons. Nuclides that have a magic number of both protons and neutrons are called “doubly magic.” They are much more tightly bound, and hence more stable, than nearby nuclides. Examples of doubly magic nuclei are 16O8 (with N = Z = 8), 132Sn50 (with Z = 50, N = 82) and 208Pb82 (with Z = 82 and N = 126).

In the early days of the nuclear shell model it was assumed that Z = 126 would correspond to a magic number for protons. Without nuclear shell effects, such a high Z might otherwise be near the upper limit beyond which Coulomb repulsion among the protons prevents nuclei from forming. However, more recent calculations that allow for deformed, rather than spherical, nuclear shapes and that take into account the Coulomb repulsion between protons suggest that the next proton magic number might be 114 rather than 126. Myers and Światecki carried out shell model calculations that suggested Z = 114 might be a proton magic number. The state with Z = 114 and N = 184 would then constitute a doubly magic nuclide. Nuclei in the vicinity of these values were predicted to have significantly longer lifetimes than other highly unstable nuclides in the vicinity, and Myers and Światecki called this region the “island of stability.” Other nuclear theorists also predicted an island of stability, though at different values of Z and N than the Myers-Swiatecki prediction. One predicted island of stability is shown in Figure II.1. It plots known and predicted heavy and superheavy nuclides as a function of Z and N. For very low values of Z, most nuclides have Z = N. However, with increasing Z the Coulomb repulsion between protons grows so that stable nuclides have N much greater than Z, as shown in Fig. I.1. Beyond uranium, nuclei with larger Z are generally short-lived; and the lifetime of these states tends to decrease progressively with larger A.

Figure II.1: A plot of isotopes of known and predicted heavy and superheavy elements as a function of neutron number N vs. proton number Z. As Z and N increase above uranium, most isotopes are highly unstable with very short lifetimes. However, theoretical calculations suggest that there may be a region around N = 184 and Z = 114, or alternatively around N = 176 and Z = 120 (as suggested in this figure) where nuclides might be unusually long-lived; this is the as yet undiscovered “island of stability.”

The most stable isotope of Rutherfordium with Z = 104 has a half-life of about 48 minutes, while the most stable isotope of Meitnerium with Z = 109 has a half-life of 4.5 seconds. But shell model calculations suggested that nuclides near the “island of stability” were likely to have much longer lifetimes, particularly because the fission barrier in this region was predicted to be quite high. Researchers looking for superheavy elements were particularly interested in probing this “island of stability.” If elements in this region had sufficiently long half-lives, then these states might have fascinating applications. For example, long-lived isotopes in the island of stability might prove useful as neutron sources for particle accelerators. They might also have military applications, since when these elements fission they would release a very large number of neutrons. Relatively stable superheavy elements could include applications in nuclear medicine, and they may be relevant to understanding the formation of elements in the universe.

Figure II.2 shows a table of the elements 110 to 118. It gives the year of discovery, the group that discovered the element, and the year that the discovery was confirmed by the Joint Working Group (JWG) and by IUPAC. All of the discoveries during this period 1995 – 2010 were made by groups at GSI Darmstadt, RIKEN in Japan, and a collaborative group between Dubna and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), occasionally also Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) which carried out chemical analyses of emitted radiation by the superheavy elements. The discoveries include nuclides in the vicinity of the predicted “island of stability.” Although isotopes that have been discovered have some interesting properties, nuclear states with extremely long lifetimes have not been discovered in this region – some calculations had predicted states with lifetimes of up to 1 billion years. As an example, the most stable isotope known for Flerovium (Z = 114) is Flerovium-289 (Z = 114, N = 175), which has a half-life of 1.9 seconds. However, this nuclide is 9 neutrons short of the predicted magic number N = 184, which has not yet been observed.

Despite the dearth of nuclides with extremely long lifetimes, researchers claim to have seen evidence that the “island of stability” region does exist. They point to the fact that some nuclides in this region have much longer lifetimes than had earlier been predicted. For example, the dominant decay mode for Flerovium-289 is alpha-decay, while earlier shell model calculations predicted that the dominant decay mode would have been spontaneous fission. The decrease in the probability of spontaneous fission is claimed to be a sign of the foothills of the “island of stability.” Thus far, researchers have been unable to produce and observe the predicted doubly magic nucleus Flerovium-298 (Fl, Z = 114, N = 184). One of the best hints of an island of stability is the comparison of two isotopes of Copernicium (Cn, Z = 112). The half-life of Copernicium-285, with N = 173, is five orders of magnitude longer than the half-life of Cn-277 with eight fewer neutrons.

| Z | Name, symbol | Discovery | Group | JWG recognition | IUPAC recognition |

| 110 | Darmstadtium, Ds | 1995 | Darmstadt | 2001 | 2003 |

| 111 | Röntgenium, Rg | 1995 | Darmstadt | 2001 | 2004 |

| 112 | Copernicium, Cn | 1996 | Darmstadt | 2009 | 2009 |

| 113 | Nihonium, Nh | 2004 | RIKEN | 2016 | 2016 |

| 114 | Flerovium, Fl | 1999 | Dubna-LLNL | 2011 | 2012 |

| 115 | Muscovium, Mc | 2010 | Dubna-LLNL-ORNL | 2016 | 2016 |

| 116 | Livermorium, Lv | 2004 | Dubna-LLNL | 2011 | 2012 |

| 117 | Tennessine, Ts | 2010 | Dubna-LLNL-ORNL | 2016 | 2016 |

| 118 | Oganesson, Og | 2006 | Dubna-LLNL | 2016 | 2016 |

Figure II.2: A list of the elements from 110 to 118 that have been approved by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). The table shows the approved name and element abbreviation, the date that the discovery was announced, the laboratory where the discovery took place, and the year that the element was accepted by the Joint Working Group (JWG) and by the IUPAC.

Our next section reviews the discovery of element 118, the last member of the seventh row of the periodic table of the elements (see Fig. I.2). The search for this element revealed a dramatic case of scientific fraud in the field of superheavy elements.

Section III: The Search for Element 118

In the early searches for superheavy elements, the group associated with the University of California at Berkeley had been the dominant research group in the production of new elements. The lead researchers in this area included nuclear chemists Glenn Seaborg and Albert Ghiorso. Beginning in 1940, Seaborg took over as leader of the team that pioneered searches for superheavy elements that don’t exist in nature. Figure III.1 shows Glenn Seaborg, who shared the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1951 for his involvement in discovering ten new elements: Plutonium (Pu, Z=94), Americium (Am, Z=95), Curium (Cm, Z=96), Berkelium (Bk, Z=97), Californium (Cf, Z=98), Einsteinium (Es, Z=99), Fermium (Fm, Z=100), Mendelevium (Md, Z=101), Nobelium (No, Z=102), and element 106 which, while he was still living, was named Seaborgium in his honor. Into the 1970s, Berkeley researchers were pre-eminent in producing and observing new heavy elements that had never before been identified.

Figure III.1: Nuclear chemist Glenn Seaborg. He headed a team of researchers at Berkeley that discovered ten new heavy elements. For this he shared the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

However, beginning in the 1970s new research laboratories began to take the lead in new element discoveries. There were active research teams at Dubna in Russia, the GSI laboratory in Darmstadt, Germany, and the RIKEN laboratories in Japan.

In 1999 a team of Berkeley researchers mounted a new effort to discover new superheavy elements. That team was led by Kenneth Gregorich and included Albert Ghiorso, who was then 84 years old. They decided to search for the element with Z = 118. Figure I.2 shows that 118 was the final element in the seventh row of the periodic table. The Berkeley group bombarded a lead target with a beam of krypton-86 ions that had been accelerated to 459 MeV. They were searching for fusion of beam and target nuclei in the following experiment:

86Kr36 + 208Pb82 → 293X118 + n (4)

293X118 → 289Z116 + 4He2

The second reaction in Eq. (4) represents element 118 decaying into a nucleus of element 116 plus an alpha-particle. The element 116 would itself subsequently decay by alpha emission, and this would be part of a chain of alpha-particle decays of this superheavy isotope. The Berkeley researchers had been inspired by calculations from visiting Polish scientist Robert Smolańczuk. He predicted that Kr and Pb would fuse with a surprisingly large cross section. Furthermore, Smolańczuk predicted the kinetic energies of the alpha particles that would arise from a chain of decays beginning with element 118 and concluding with element 106. He also predicted that the half-life of element 118 (the time during which half of the produced nuclides would decay into element 116 plus an alpha particle) would be between 31 and 310 milliseconds.

One of the members hired by the Berkeley team was Victor Ninov. Ninov, who was born in Bulgaria and who is shown in Figure III.2, had been a participant in GSI experiments on superheavy elements. He was a particularly valuable researcher for this collaboration because he had written a computer code called GOOSY that could search through the data and attempt to find tell-tale “signatures” of the formation of superheavy elements. The GOOSY code would look for examples where the superheavy nucleus might form, and then observe decays to other nuclei via alpha particle emission. Those nuclei would themselves decay by alpha emission, so a superheavy element could be identified by observing a “chain” of alpha-particle decays. The kinetic energies of the alpha particles, and the time required for a superheavy element to decay by emitting an alpha particle, would be measured and compared with theoretical calculations. The locations of all particles would be measured to prove that they all arose from production of a single superheavy ion. In 1995 and 1996, Ninov’s group at GSI had announced the discovery of three new superheavy elements with Z = 110, 111 and 112. They produced element 112 by using zinc beams (with Z = 30) to bombard a lead target (with Z = 82). Ninov had single-handedly written, run and evaluated the GOOSY code that had apparently shown evidence for those three superheavy elements.

Figure III.2: Researcher Victor Ninov. He was hired by Berkeley for the element 118 search because of his expertise in superheavy element research. In particular, he had written a computer code to search for superheavy elements at the Darmstadt GSI facility, and he adapted this code for the Berkeley superheavy search.

Figure III.3 shows the experimental system that was set up at the 88-inch cyclotron facility at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL). “A beam of krypton ions (from the beam pipe coming from the right) crossed a rapidly spinning wheel of thin lead targets (not visible here) just in front of the first of three large magnets (in blue housings) that would separate the desired composite nuclei created in the targets from beam and target debris. The composite nuclei passed through a long low-pressure helium chamber that recharged them all to roughly the same ionization state as they traversed the bending and focusing fields on their way to the silicon detector plane beyond the last magnet.” The system, called the Berkeley gas-filled separator or BGS, was designed to capture any ions of element 118 in a silicon detector plane that would record exactly where the ion came to rest. The system would also record the times and energies of alpha particles that would be emitted in a series of reactions that denoted intermediate decays of heavy nuclei. The first decay reaction, where element 118 decayed to an ion of element 116 plus an alpha particle, is shown on the second line of Eq. (4).

Figure III.3: The experimental setup for the superheavy element search at the LBNL 88-inch cyclotron. This constituted the Berkeley Gas Separator system that was designed to detect ions of element 118 and its decay products.

The Berkeley experiment ran in two stages, first from April 8-12, 1999, and second from April 30 – May 4. As he had written the analysis computer code, Victor Ninov personally processed and analyzed all the data from this experiment. In fact, no one else on the experiment knew how to work with the raw data that originated in the detectors and was stored digitally on magnetic tape. After the first experimental run, Ninov announced to his team that he had found three examples of the formation of element 118. He claimed that the data showed alpha particles that resulted from the decays of elements 118 to a series of lower-mass ions. It was claimed that the Berkeley group data showed a chain of alpha decays leading all the way from element 118 to element 106. After the second experimental run Ninov announced one additional example of element 118. In these reactions, the Berkeley team would have discovered new elements with atomic numbers 118 and 116 — and possibly also element 114, if an earlier element 114 discovery claim by the Dubna – LLNL group turned out to be erroneous. In Figure III.4, we show a schematic sketch of the superheavy element decay chain that Ninov reconstructed from his data analysis and showed to his collaborators. And in Figure III.5 we show the final decay chains that the Berkeley group published to confirm their discovery.

Figure III.4: The formation of element 118 and the chain of alpha-particle decays that eventually led to element 106. In April 1999, Ninov showed this hand-written sketch to his Berkeley collaborators to announce that their experiment had discovered not only element 118 but also element 116 (and possibly 114), which had never before been observed. In this sketch, Ninov included the kinetic energies of the alpha particles plus the elapsed time before another alpha particle was released.

Figure III.5: The Berkeley group claimed to have observed the formation and at least five of the six-alpha-particle decay chain of three produced ions of element 118. For each ion, they displayed the energy of the alpha particles produced in the subsequent decay chain and the time elapsed before each successive element emitted an alpha particle. This comprised a chain of six decays that eventually led to element 106.

The results were in extremely good agreement with the theoretical calculations by Smolańczuk. The Berkeley group was elated that their experiment had apparently discovered two or three new superheavy elements. After extensive calculations and studies, the group dropped one of the element 118 candidates, but this still left them with three examples of this new element. From Fig. III.5, we see that the group claimed to have observed 17 of the 18 alpha particles resulting from a chain of decays leading from three nuclei with Z=118 and N= 175 to 269Sg (Seaborgium, Z = 106). Furthermore, they had observed formation of at least one ion of element 118 in both of their experimental runs, so the superheavy element formation seemed to be reproducible. The Berkeley group felt that they needed to move rapidly. In particular, in 1998 a joint collaboration between researchers from Dubna and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) had announced the discovery of element 114 by shooting a beam of Calcium-48 ions into a Plutonium target. That group, under the leadership of Russian scientist Yuri Oganessian might have begun a search for element 118; and they had ready access to krypton beams and a lead target. In a paper published in Physical Review Letters (PRL) in August 1999, the Berkeley team announced their experimental discovery of three examples of element 118 production and decay.

The discovery of new elements by this technique was major news. It was reported in the prestigious journal Science, and also was reported by the New York Times. It set off a worldwide series of searches designed to verify these results. Every lab with the capability of mounting a search for superheavy elements conducted such experiments. The GSI group in Darmstadt conducted a search beginning in summer 1999; however, they found no evidence of element 118. Research groups in Japan and France also repeated the experiment and found no sign of that superheavy element. This was puzzling because the Berkeley results established a cross section for formation of element 118. If one ran, for example, an experiment with five times the number of reactions as Berkeley, one would expect to see five times as many examples of element 118. The earlier Berkeley results could conceivably have been a statistical fluctuation; as there is some randomness in the occurrence of these reactions, the earlier experiments could just have been lucky. But it was relatively straightforward to test statistical fluctuations by running for a sufficiently long period of time.

In spring 2000, the LBNL group repeated their own experiment, and this time they also found no examples of element 118. The group examined every possible explanation for the lack of positive results. One reason that Ninov was not immediately suspected of producing fraudulent ‘events’ was that he was undoubtedly a highly skilled researcher. Berkeley colleagues such as Gregorich and Ghiorso gave high praise to Ninov’s abilities in superheavy element research.

In April 2001, the Berkeley group mounted another experimental run, after they had improved the detection apparatus and the statistical analysis techniques. At this point, Victor Ninov announced another positive identification of an element 118 ion. However, by this time a postdoctoral researcher working on the experiment, Don Peterson, had learned how to use Ninov’s GOOSY program. The GOOSY program managed a set of subsidiary computer files that could carry out the data analysis. So Peterson wrote his own data analysis code and connected it to GOOSY. When he ran the analysis program for the 2001 experiment, he found no examples of element 118. Ninov and other collaborators re-analyzed the data and also found no trace of element 118. At this point, Berkeley researchers returned to the raw data files from their original 1999 experiment (this proved to be quite challenging), and they found no 118 decay chain events.

Next, LBNL appointed an internal review committee to investigate this situation; this committee included computer experts. When they examined the 1999 results, they found that the processed files of the data did contain the 118 decay chains, but the unprocessed raw data files did not show these data. In the raw data files, the investigators could find examples of alpha particles with the claimed energies, but spatial and timing analysis showed that those particles were not connected with production of a superheavy ion. And finally, the processed data ‘showing’ the production of element 118 and its decay chain had clearly been altered in some fashion. Now, LBNL convened an external review committee to review the situation. At this point Gregorich released a statement withdrawing the Berkeley claim to have discovered element 118. The external review committee found that none of the raw data files from either 1999 or 2001 contained any evidence for element 118. But the processed data files did contain the data chains that had been cited as proof of the production of element 118.

Furthermore, log files from the experiment showed evidence that someone using the account “Vninov” had inserted bogus “element 118” events into the processed data. Since Victor Ninov was the only person who initially knew how to run the data analysis program, he was the logical suspect to have tampered with the raw data files. However, Ninov adamantly insisted that he had not messed with the data files. He claimed that his password was well known to his colleagues, and that someone else could have changed the data in an attempt to destroy his reputation. In July 2001, the Berkeley group submitted a note to PRL attempting to retract its claim to the discovery of element 118. However, PRL initially refused to run the retraction; at the time, PRL policies would not accept retraction of a paper unless it was signed by all authors from the initial paper. In this case, Victor Ninov refused to sign the retraction, claiming that it was premature to retract the claim until the matter had received more study. But eventually in July 2002, Physical Review Letters accepted and published an “Editorial Note” with an explanation that “All but one of authors of original Letter have asked us to publish following retraction.”

Now that Ninov appeared to be the only person capable of fraudulently altering the data files, his former collaborators at the Darmstadt GSI laboratory went back and analyzed the raw data from their experiments from 1994 to 1996, that had claimed to find elements 110 to 112. Once again, Ninov was the only person who had been able to run his data analysis program. The GSI group found that two of the superheavy element decay chains reported in their papers did not exist in the raw data files! The group found possible evidence that Ninov may have been fabricating alpha decay chains since 1994. However, the GSI researchers also found some genuine examples of element 112 formation, in addition to the fraudulent ones. And in the years since the 1994 experiment, several other research labs had confirmed the observation of elements 110 – 112, so the GSI claim did not have to be retracted.

In November 2001, LBNL appointed an external review committee chaired by Caltech Emeritus Professor Rochus Vogt to investigate the element 118 affair. After reviewing evidence from both Berkeley and GSI, in March 2002 the Vogt committee concluded “We find clear and convincing evidence that data in 1999, upon which reported discovery was based were fabricated … our findings revealed intentional fabrication … instead of honest error or honest differences in interpretation … clear evidence that Ninov [carried] out this fabrication … if anyone else had done [it], Ninov would almost surely have detected it.” In May 2002, Victor Ninov was fired from LBNL. However, he continued to profess his innocence and unsuccessfully appealed his firing.

Section IV: Summary

It is now apparent that someone tampered with the data files from the 1999 Berkeley effort to discover superheavy element 118. In 2006, a joint GSI- LLNL experiment managed to isolate some samples of element 118. The alpha particle decay energies and half-lives differed significantly from the now-retracted Berkeley results. For their successful effort to discover element 118, the experimental team was allowed to suggest a name for that element, and also elements 116 and 117 that were discovered. They chose Livermorium for element 116, Tennessine for element 117 (researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee had participated in chemical analyses of the heavy elements), and Oganesson for element 118 (named for Yuri Oganessian, the leader of the Dubna superheavy-element research team). In agreement with nomenclature for the elements in the periodic table, the name for element 118, the final element completing the 7th row in the periodic table, ended in -on (as for other members of column 18 of the periodic table such as Neon, Argon, Radon, etc), while the name for element 117, the next-to-last element in the 7th row in column 17 of the periodic table, ended in -ine (as in Fluorine, Chlorine, etc).

Despite Victor Ninov’s unrelenting statements about his innocence, it is not feasible that anyone else could have perpetrated the fraud. Since no one else in the collaboration knew how to run Ninov’s program before 2001, it is hard to imagine how anyone could have inserted the “fake” signatures of element 118. It is equally hard to imagine how this could have occurred without Ninov’s knowledge, particularly since the Berkeley collaboration spent months re-working the detectors and improving the statistical analyses. And since the GSI collaboration found some spurious “signals” in the processed data from their 1994 experiments that discovered elements 110 – 112, where once again Ninov was the only person running the data analysis software, it is not credible that the same person could have altered both the GSI and Berkeley raw data to insert false signatures and implicate Ninov.

The Vogt Committee Report ended with strong statements regarding the fact that Victor Ninov was the only researcher who examined the data files before the Berkeley group claimed their discovery. “We find it incredible that no one else in group, other than Ninov, examined original data to confirm purported discovery of 118.” Initially, researchers at LBNL pushed back against this criticism. They claimed that collaborative research is built on trust that all members of a team are behaving honestly, and that it is extremely difficult to detect or root out fraud in experiments carried out by a team of researchers.

However, spurred on by the frauds perpetrated by Ninov and Jan-Hendrik Schōn (we will discuss this second fraud in a separate post in this series on fraud in physics), in November 2002 the American Physical Society (APS) released new guidelines for ethical behavior in research. These new guidelines stated “Prompted by recent highly publicized episodes of misconduct in physics, the APS has updated and expanded its professional ethics guidelines. The changes, adopted November 10, 2002, at the APS Council meeting, clarify the roles and responsibilities of coauthors.” The report continued, “All coauthors share some degree of responsibility for any paper they coauthor … some coauthors have responsibility for the entire paper. These include, for example, coauthors who are accountable for the integrity of the critical data reported in the paper.”

The APS guidelines were the result of a lengthy examination of the process that goes into scrutiny and publication of a collaborative work. Many physicists who were senior collaborators in research groups protested that the new APS guidelines were unfair and unreasonable. For example, some researchers claimed that, as the leaders of a research group and the principal investigators on research grants, the granting agencies insisted that their names be added to all research publications from their group. They claimed it was unreasonable to assume that they understood every detail of every paper that included their name. Other researchers pointed out that the high-energy experimental physics papers announcing the discovery of the Higgs Boson in 2012 listed over 5,000 co-authors; they claimed that it was impossible that every researcher on that paper understood every aspect of the experiments leading to this discovery claim.

We have little sympathy for those arguments. First, if a senior researcher does not understand the important aspects of a paper claiming a major discovery, they should not add their name to that paper. One of the reasons for the new APS ethics guidelines is that over the years when results were shown to be wrong or even fraudulent, senior researchers frequently argued that, as very important and busy people, they could not possibly be held responsible for the publication of false results. These researchers often received major awards when those discoveries turned out to be correct; but when results turned out to be false or even fraudulent, the senior investigators simply washed their hands of any personal responsibility. Note that requiring independent confirmation of data by independent individuals (and, where possible, using independent analysis software) not only minimizes the possibility of fraud, but also minimizes the likelihood that honest mistakes or inadvertent programming bugs reach the publication stage. As for the argument regarding the 5,000 co-authors on the Higgs Boson discovery, it is typical for such large collaborations to have at least two groups that independently carry out important segments of the analysis, and then compare their results. Furthermore, physics colliders generally host two major detectors with independent collaborations and require that the two have consistent data before announcing any major discovery. This was certainly the case for the Large Hadron Collider and the papers reporting the Higgs boson discovery in 2012. These efforts ensure the integrity of the analysis of data arising from the experiments.

Also, both the Ninov and Schōn affairs involved research that was touted as a major discovery in physics. In those circumstances, having only a single individual responsible for a key component of the experiment, and never checking their results by other members of the collaboration, left the experiments vulnerable to errors or fraud. In our opinion, senior leaders of research groups need to take steps to prevent sloppy or dishonest activity in experiments that claim important advances in the field – and they need to acknowledge their personal responsibility when mistakes or fraud arise. The new APS guidelines reflect the opinion of a large segment of the physics community that agrees with these ethics statements. Scientific collaborations operate under the assumption that their colleagues are behaving honestly. The new APS guidelines suggest that scientific collaborations should operate under the guideline “trust, but verify.”

Finally, we take up the question of whether science is self-correcting. This is an issue that has been debated in public and scientific communities; there are a number of politicians and journalists who argue that science is not self-correcting. However, in this instance (and in the two other cases of scientific fraud in this series of posts) there appears to be strong evidence that the correction claimed by scientists was in fact working. First, we emphasize that our claims of self-correction in science are limited to cases where the claimed results represent real breakthroughs and are important. It is equally important that the results are not so dependent on poorly recorded local and environmental conditions that the experiments cannot be replicated elsewhere; dependence on such confounding variables sometimes afflicts small-sample biomedical and epidemiological research. In the case of reproducible breakthroughs, other groups will attempt to either replicate the claims or to advance beyond the original discovery. Here, every laboratory with the resources to test these superheavy element claims rapidly mounted their own trials. When no other lab could reproduce the results of the Ninov group, they reported this and spurred the LBNL group to repeat their experiment. When all of these efforts at replication failed, the LBNL group worked feverishly to understand their conflicting results. Finally, the Berkeley team discovered that the raw data showed no superheavy decays, while the processed data exhibited evidence for superheavies. Upon further investigation, they determined that the raw data had been tampered with. At this point they publicly retracted their discovery claim and the scientific paper was retracted.

Note that the self-correction process occurred rather rapidly. As the Vogt committee pointed out, the original discovery claim could have been averted if the research team had insisted that the data be processed by more than one individual. However, otherwise the “self-correction” process worked here, just as is claimed by proponents of the scientific method.

Source Material:

Lawrence Berkeley Lab Concludes That Evidence of Element 118 Was a Fabrication, Bertram Schwarzschild, Physics Today 55, 9 p. 15 (2002). https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/article/55/9/15/757318/Lawrence-Berkeley-Lab-Concludes-that-Evidence-of

V. Ninov et al., Observation of Superheavy Nuclei Produced in the Reaction of 86Kr with 208Pb, Physical Review Letters 83, 1104 (1999); Retraction, Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 039901 (2002). https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.1104

Victor Ninov’s ‘Discovery’ of Element 118: A Case of Alleged Data Fabrication, Mark Yashar, U.C. Davis Physics Dept, June 1, 2007 http://yclept.ucdavis.edu/course/280/Ninov_Yashar.pdf

APS Expands and Updates Ethics and Professional Conduct Guidelines for Physicists, APS News, January 2003, https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200301/guidelines.cfm

Searching For the Island of Stability, Glenn Seaborg Institute, Livermore Lab https://seaborg.llnl.gov/research/superheavy-element-discovery

Getting to the End of Matter, Livermore-Dubna Collaboration https://str.llnl.gov/december-2016/stoyer

Collaboration Expands the Periodic Table, One Element at a Time, Science & Technology Review Oct 2010 https://str.llnl.gov/content/pages/past-issues-pdfs/2010.10.pdf

The Quest For Superheavy Elements and the Island of Stability, C. Dullmann and M. Block, Scientific American Mar. 1, 2018 https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-quest-for-superheavy-elements-and-the-island-of-stability/

Hunt for the Superheavies, H. Johnston, Physics World Mar 2, 2021 https://physicsworld.com/a/hunt-for-the-superheavies/

Wikipedia, Superheavy Elements https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superheavy_element

Wikipedia, Island of Stability, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Island_of_stability

Wikipedia, Victor Ninov https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victor_Ninov

More Elemental Fraud? , Charles Seife, Science July 17, 2002 https://www.science.org/content/article/more-elemental-fraud

The Element That Never Was, Kit Chapman, Chemistry World June 10, 2019 https://www.chemistryworld.com/features/victor-ninov-and-the-element-that-never-was/3010596.article?adredir=1

The Scientific Fraud Behind the “Discovery” of Element 118, Bigthink.com, June 12, 2023 https://bigthink.com/the-past/uc-berkeley-ninov-elements/

Atomic Lies: How One Physicist May Have Cheated in the Race to Find New Elements, Richard Monastersky, Chronicle of Higher Education, Aug. 16, 2002 https://www.chronicle.com/article/atomic-lies/

H. Kragh, From Transuranic to Superheavy Elements: A Study of Dispute and Creation, Springer 2018, ISBN 978-3-319-75813-8 https://books.google.com/books/about/From_Transuranic_to_Superheavy_Elements.html?id=RuBLDwAAQBAJ

W.D. Myers and W. Swiatecki, Nuclear Masses and Deformations, Nuclear Physics 81, 1 (1966). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0029558266906390

What are Superheavy Elements?, Labmate, Jan. 27, 2016 https://www.labmate-online.com/news/news-and-views/5/breaking-news/what-are-superheavy-elements/37596

Maria G. Mayer, On Closed Shells in Nuclei, Physical Review 74, 235 (1948). https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstract/10.1103/PhysRev.74.235

O. Haxel, J.H.D. Jensen and H.E. Suess, On the “Magic Numbers” in Nuclear Structure, Physical Review 75, 1766 (1949). https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstract/10.1103/PhysRev.75.1766.2

D. Engber, Is Science Broken? Or is it Self-Correcting? Slate.com, Aug. 21, 2017 https://slate.com/technology/2017/08/science-is-not-self-correcting-science-is-broken.html

James Glanz, Element 118, Heaviest Ever, Reported for 1/1000th of a Second, New York Times, Oct. 17, 2006 https://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/17/science/17heavy.html

ATLAS and CMS Publish Observations of a New Particle, CERN Press Release, Sept. 10, 2012, https://home.cern/news/news/experiments/atlas-and-cms-publish-observations-new-particle