Update Posted Sept. 26, 2024:

Our blog post on private equity (below) discusses the various steps that private equity firms take to extract the maximum amount of money from the firms that they take over, in the shortest amount of time. We show that in many cases, otherwise healthy firms go bankrupt after private equity takeovers. The practices of private equity firms are often disastrous for these businesses, although they are immensely lucrative for the private equity firms. However, when private equity firms take over healthcare businesses, the results can not only represent a financial disaster for these healthcare firms, but can result in shoddy care and even life-threatening results for patients of these systems.

In May 2024, Steward Health Care, the largest for-profit private hospital chain in the U.S., filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. From 2010 to 2020, Steward Health Care was owned by the private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management. Here, we will outline how Cerberus gutted the hospitals they owned, how they extracted hundreds of millions of dollars from these hospitals but left them crushed by unnecessary debt. Steward has become the poster child for the abuses perpetrated by private equity firms when they take over healthcare systems, and the CEO of Steward Health Care, Ralph de la Torre, is now a symbol of the excesses of the private equity system in health care. Fig. 1 shows the current corporate headquarters of Steward Health Care in Dallas, where they moved from Boston in 2018. Here is a timeline of the Steward Health Care system, and their private equity managers.

Figure 1: The corporate headquarters of Steward Health Care. Steward moved its headquarters from Boston to Dallas in 2018.

Figure 2: Dr. Ralph de la Torre, the founding CEO of Steward Health Care.

- 2010: Private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management creates Steward Health Care when it purchases a non-profit Catholic health system that ran 6 hospitals in Massachusetts. Cerberus pays $895 million for the hospitals, and loads Steward with $475 million in assumed debt. The Cerberus deal is brokered by Ralph de la Torre, the head of the Caritas Christi Catholic hospitals. De la Torre convinces Cerberus to take the hospitals private, and he is named CEO of Steward Health Care. Fig. 2 is a photo of Dr. de la Torre.

- 2016: Steward sells the real estate of its Massachusetts hospitals for $1.2 billion to a group called Medical Properties Trust (MPT). This means that these hospitals no longer own their buildings; they will have to pay rent forever going forward, owing millions of dollars in completely unnecessary lease payments. The “lease-buyback” transaction is a scheme used widely by private equity firms; it generates a large amount of profit for the firm, while saddling the hospitals with millions of dollars in leases. When private equity firms purchase a business, they typically put up a fraction of the purchase price. The remaining money is added as debt to the purchased entity. This leaves the purchased firm with a heavy load of debt; however, when even more debt is piled on from a lease-buyback transaction, it is likely to prove fatal to the firm. And this was the case for Steward Health Care.

- To the best of our knowledge, there is no direct connection between MPT and Cerberus. However, MPT is now charging Steward exorbitant rent for properties that Steward previously owned. Both Cerberus and MPT also charged large management fees to Steward. Steward uses money from the sale of its hospitals to purchase eight more hospitals for $311.9 million; it turns around and sells those hospitals to MPT for $301.3 million.

- 2016: Steward pays a $790 million dividend, with the lion’s share ($719 million) going to Cerberus and $71 million going to de la Torre and his management team. Cerberus uses the income to finance a $484 million dividend to one of its funds. However, Steward declares a $300 million loss for 2016. At the end of 2016, Steward’s liabilities exceed its assets by $910 million.

- 2017: Steward Health Care International (supposedly independent of Steward Health Care, although Ralph de la Torre was on the board of both companies) signs an agreement to take over administration of three hospitals in Malta. De la Torre and Maltese Prime Minister Joseph Muscat praised the deal. However, in years to come, Steward missed all of its reporting deadlines, even after seeking extensions. By 2023, the company had produced just a one-page affidavit and 76 pages of photographs. In May 2024 a Maltese judge annulled the Steward – Malta contract; he found that Steward had acted to “unjustly enrich itself at the expense of citizens,” and had engaged in “possible criminal behavior.” It was also alleged that Steward had used Maltese taxpayer funds for kickback schemes and bribery of politicians via opaque ‘consultancy fees.’ Fig. 3 shows St. Luke’s Hospital in Malta, one of the hospitals operated by Steward Health Care International. In Jan. 2023, it was described as being in a state of “neglect and abandonment.” Malta brought criminal charges against Steward Health Care International’s lawyer and IT manager. And in July 2024, it was revealed that the U.S. Department of Justice had opened a criminal investigation against Steward Health Care over allegations of fraud and corruption. Steward was accused of violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which prohibits businesses from bribing foreign governments as a means of obtaining business.

Figure 3: St. Luke’s Hospital in Malta, one of three Maltese hospitals operated by Steward Health Care International. In Jan. 2023, St Luke’s was described as being in a state of “neglect and abandonment.” In May 2024, Maltese judges nullified the 2017 agreement between Steward and the Maltese hospitals.

- 2017: With the help of MPT, Steward uses some of the money from the dividend to expand from 11 hospitals in Massachusetts to 37 hospitals around the U.S.; it is now the largest for-profit private hospital operator in the U.S. Among the hospitals purchased were eight struggling hospitals in three states. One of these chains was Iasis Healthcare. But Steward absorbed a debt estimated at 6.5 times Iasis’ earnings. Ninety-nine percent of the $304 million transaction was financed by MPT, which purchased the real estate of all eight hospitals and then leased them back to Steward.

- 2018: Steward closes two of the hospitals it has recently acquired, resulting in layoffs of at least 1,113 workers. It also cuts back on services at other hospitals. Over the next few years it will lay off staff, cut back on services, and fail to pay many vendors.

- 2020: In May 2020, Cerberus issues a $350 million promissory note to a group of Steward executives. If Steward should subsequently declare bankruptcy, then as a bondholder Cerberus would have priority over stockholders in claims on the Steward assets.

- 2020: Cerberus prepares to sell off Steward. MPT provides a $335 million payment to a new set of physician owners, plus it invests $400 million into the Steward system. But Steward will show a $408 million loss in 2020. Although Cerberus claims that it was a good administrator and that the Steward system prospered under its leadership, it lied. Already by 2016, the Steward system was so burdened by debt that it was bound to go under in the next few years.

- 2020: During the 10 years that Cerberus owned Steward, it made $800 million in profits; this quadrupled the firm’s initial investment in the hospital chain. Around the time that Cerberus cashed out, Steward paid its ownership a $111 million dividend. Shortly after that Steward CEO Ralph de la Torre bought a $40 million yacht. Steward also “purchased two private jets and a private suite at Dallas’ AA Arena.”

- 2021: Steward borrows $335 million from MPT. This makes MPT Steward’s landlord, largest creditor, and its minority owner. Steward then purchases five Florida hospitals for $1.1 billion from Tenet Healthcare; MPT enters a sale-leaseback agreement with Steward where it pays $900 million for those hospitals. In 2022, MPT announces that Steward has paid it $1.2 billion in rent and mortgage interest since 2016.

- 2023: By this time, Steward is clearly in financial distress. It has “missed rent payments, mounting patient care issues, and reports of unpaid bills to vendors. That year, Steward took on $600 million more in debt to refinance debt it already had.”

- 2023: The Boston Globe Spotlight team investigated the Steward Health Care system. They find that while Steward was stiffing vendors and patients at their hospitals were being injured or killed due to insufficient staffing and supply shortages, Steward continued to spend large sums on “investor dividends, executive bonuses, private investigators (Steward spent millions investigating people who criticized their practices), and non-business-related travel.” In addition, the Globe team found several instances where money from Steward Health Care was provided for de la Torre’s private benefit, or to ventures owned by him.

- 2024: On May 6, Steward Health Care files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. They report over $9 billion in liabilities, of which $6.6 billion are long-term lease liabilities owed to Medical Properties Trust. Steward owed $1 billion to vendors and medical suppliers, had $1.2 billion in loan debts, and owed nearly $290 million in unpaid compensation to employees. Since 2018 Steward has closed six hospitals resulting in layoffs of at least 2,650 workers. In other facilities they have cut important services such as obstetrics, behavioral health, and cancer care. Steward announces that it intends to auction off all of the hospitals that it owns.

- 2024: Bankruptcy filings show that Steward paid about $30 million per year to Management Health Services for “executive oversight and overall strategic directive.” MHS was partly owned by de la Torre; in 2019, he was paid $6.3 million by MHS over a 10-month period.

- 2024: In 2018, Steward moved its operations from Massachusetts to Dallas, Texas. When Steward declared bankruptcy, it did so in the ‘scandal-plagued’ and ‘notoriously debtor-friendly’ bankruptcy court in Texas.

- 2024: On August 13, 2024 the Rural Healthcare Group or RHG announced that it would purchase Steward Medical Group and the Steward Health Care Network. RHG itself is owned by a private equity firm, Kinderhook Industries LLC. RHG was not purchasing the hospitals owned by Steward; they were separating off the clinics and staff that provided patient care. Those clinics will now transition from being owned by the hospitals to independent; RHG claimed that this move “Will improve the patient and provider experience while enhancing the overall quality of care.”

- 2024: On Sept. 12, 2024 Steward and its landlord, Medical Properties Trust, came to an agreement that it claimed would allow it to exit bankruptcy court and operate 15 hospitals. The two groups, who had been suing each other, agreed that MPT would forgive $9.5 billion in outstanding obligations. Steward would be allowed to receive $395 million from sale of a hospital in Florida. That amount would then be paid to Steward’s lenders and unsecured creditors. In return, Steward waived its rights to pursue lawsuits against MPT. Various different hospital operators signed on to manage Steward’s hospitals, either on an interim basis or a permanent basis. The bankruptcy judge Christopher Lopez called the settlement “nothing short of remarkable.” However, the agreement was not cheered by all parties. An unsecured creditor committee said that their investigations showed that more than a billion dollars owed by Steward to MPT were “fraudulent or preferential transfers,” and that MPT had leveraged Steward’s “desperate liquidity situation” to force a deal.

- 2024: On Sept. 12, 2024 the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee held a hearing that focused on Steward’s financial practices. Much attention has been focused on the incredible profits made by the private equity firm and managers of the Steward hospitals, at the same time that Steward staff members struggled to deliver health care without adequate staffing, equipment or supplies. Much of the focus has been on Dr. Ralph de la Torre, whose extravagant reimbursement of reportedly $250 million from Steward led to his purchase of a $40 million yacht, $15 million sport fishing boat and a 500-acre ranch in Texas. This contrasted sharply with the closing of Steward hospitals, and Steward’s filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in May. After de la Torre refused to attend the Senate committee meeting, the committee passed two resolutions. One would instruct the Senate lawyers to file a civil suit charging him with contempt of Congress; the second resolution would refer the Steward Health Care matter for possible criminal prosecution. On Sept. 25, the full Senate unanimously held de la Torre in criminal contempt of Congress; this was the first time since 1971 that the Senate found someone in criminal contempt.

The Private Equity Stakeholder Project investigated the situation with Steward. They issued a report, The Pillaging of Steward Health Care. That report listed several recommended policy steps by states, including the following:

- States should require full financial transparency of hospital owners and all of their investors.

- Give the state authority to put mismanaged hospitals into receivership.

- Place limits on the amount of debt that can be assumed in hospital buyouts. Bar or severely limit “dividend recapitalization” tactics, where investors load hospitals with additional amounts of debt.

- Bar or severely limit sale-leaseback arrangements. In such cases private equity firms sell the hospitals and their land, and then require the hospitals to pay rent to the new landlords.

- Place limits on management fees.

All of these recommendations seem to be the least that states can do to prevent private equity firms from outrageous financial structures that enrich management while driving health care systems into bankruptcy. No wonder that the words “plunder” and “pillage” are frequently used to describe the financial machinations of private equity firms in the health care arena.

Update Posted April 14, 2024

After our blog post on private equity, there has been considerable attention paid to the role of private equity in healthcare (see Section III of this blog post and the update that we posted on Jan. 17, 2024).

- First, a 2024 survey conducted by the American College of Physicians found that physicians held very negative opinions regarding the role played by private equity in healthcare. The majority of physicians who were surveyed were in the field of general internal medicine. Of the 525 physicians who responded to the survey, 60.8% viewed private equity involvement as negative, compared to 10.5% who viewed it positively (28.8% of those who responded were neutral). Dr. Jane Zhu, the lead author of that survey, said that “Clinicians themselves are concerned about the effects of private equity on their own practice and on their patients.”

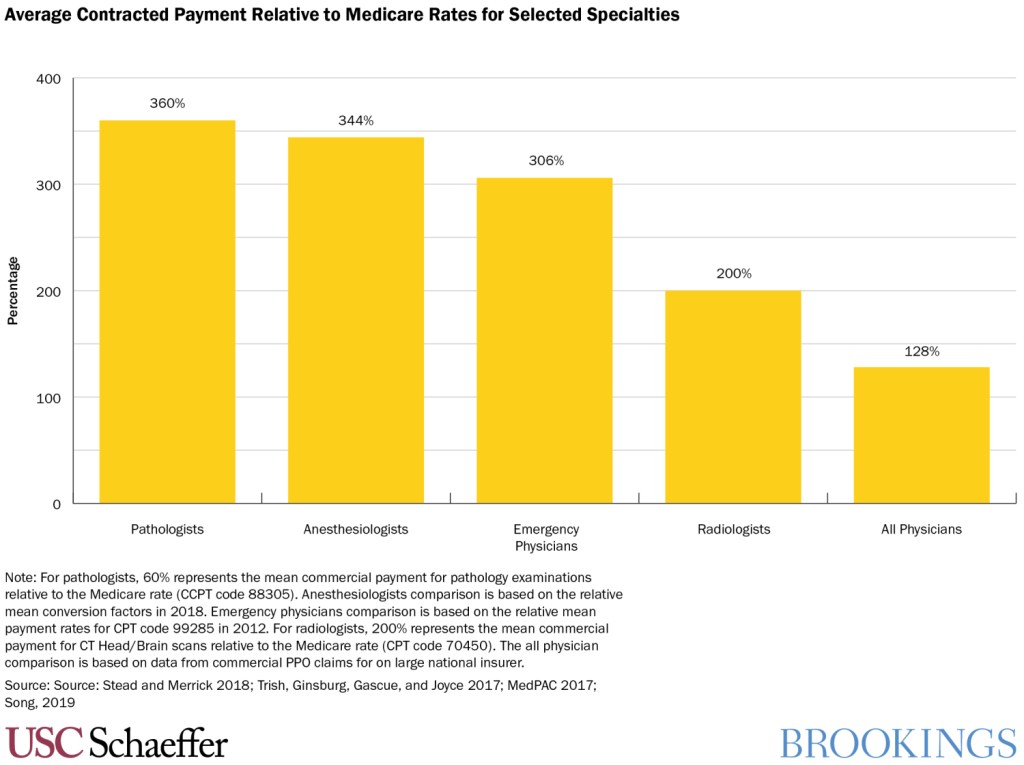

Initially, private equity tended to focus on profitable specialties such as radiology, dermatology, emergency medicine and gastroenterology. To phrase the survey results in a different way, “52.0% of physicians viewed private equity ownership as worse or much worse than independent ownership, and 49.3% considered it as worse or much worse than not-for-profit or healthcare-system ownership.” And over half of those surveyed had a negative view of private equity on the subject of physician well-being, healthcare prices or spending, and health equity.

Dr. Zhu and Dr. Dov Baruch published a 2023 paper in Health Affairs showing that when physician-owned practices were acquired by private equity they experienced higher rates of turnover, plus they placed increased reliance on physician assistants and nurse practitioners rather than on doctors. Those conducting the survey noted that only 5.5% of the respondents worked for a firm owned by private equity, so they cautioned about drawing sweeping conclusions from this survey. Dr. Sailesh Korda of the University of Florida Health System has studied the role of private equity in dermatology. He stated “Doctors from all over the country have shared with me their negative experiences with private equity-backed groups placing profits over patients.” Korda also noted that “Many physicians are unable to voice their concerns publicly due to non-disparagement clauses in their contracts.”

- On April 3, 2024, the US Senate Subcommittee on Primary Health and Retirement Security focused on “the broader impacts on healthcare professionals and their patients, as well as an expressed need for greater transparency in healthcare transactions, especially those involving private equity.” Eileen O’Grady, research and campaign director for healthcare at the Private Equity Stakeholder Project testified, “Private equity firms are short-term investors. They usually try to own companies for 4 to 7 years. During that time, they have to generate as much cash flow as possible.” As we detail in our post, this leads to a number of practices that maximize short-term returns to the private equity firms, but that are completely contrary to the goal of healthcare companies to provide their patients with high quality, effective care at a reasonable cost.

Private equity firms generally purchase companies through leveraged buyouts that offload a tremendous amount of debt onto the purchased company. They then may compound that debt load by dividend recapitalization, which amounts to a further debt burden for the purchased company and provides the private equity firm with a cash payout. They may also use sale-leaseback transactions, where a healthcare organization’s real estate is sold, and the organization is required to lease back real estate that they formerly owned. In addition, private equity companies are notorious for cutting costs when it comes to staff, medical supplies, equipment and charity care.

Senator Edward Markey, the chair of the subcommittee session, stated that “Patients and communities suffer when companies freely put corporate greed over community need. Frustratingly, our system allows – even rewards – this strategy. Private equity companies across the country are quietly making profits while infiltrating everything from fertility care to hospice care.”

The meeting focused on the recent sale of the financially troubled Steward Health Care nationwide physician practice to UnitedHealth subsidiary Optum. In 2010 the non-profit Caritas Christi health system was purchased by Cerberus Capital Management for $800 million. The company now operates more than 30 hospitals and is currently the nation’s largest private non-profit hospital chain. However, Cerberus has been selling off its stake in Steward. This leaves Steward with crippling financial liabilities, and critics fear that this will lead to further shutdowns of hospitals.

- Chris Hamby of the New York Times has identified a troubling practice involving health insurance reimbursements for medical treatments. They involve a private-equity-owned data analytics firm called MultiPlan. It works with large insurers such as UnitedHealthcare, Cigna and Aetna to determine reimbursements when patients obtain services from out-of-network providers. MultiPlan claims that their algorithms recommend “reimbursement that is fair and that providers are willing to accept in lieu of billing plan members for the balance.” However, what MultiPlan fails to mention is that they have a deal with the insurers whom they advise. When they recommend a low reimbursement to a medical provider, they pocket a hefty fee for processing that claim, and furthermore they give the insurance company a cut of the savings. MultiPlan claims that their calculated reimbursements prevent “rampant overbilling” by some doctors and hospitals. Of course, this is a real problem and needs to be tackled at some level. In fact, as shown in our blog post, after private equity took over physician groups and hospital chains, they often began billing at obscenely high rates. Before MultiPlan began advising insurance companies, insurers used a non-profit database FAIRHealth to calculate reasonable medical reimbursement rates. However, since FAIRHealth based their payments on what doctors typically charged, insurers claimed that using this database would lead to excessive reimbursements.

When MultiPlan was founded in 1980, the company offered a traditional approach to managing out-of-network claims by negotiating rates with providers. Their agreement with insurers guaranteed that individuals would be charged any additional fees. But after being taken over by private equity, MultiPlan changed their algorithms so that they recommended lower reimbursements, and they abandoned their assurance that individuals would not be billed for the difference. The New York Times obtained internal e-mails from Cigna executives. “We cannot develop these charges internally. We need someone (external to Cigna) to develop acceptable rates.” In 2009, the New York State Attorney General had investigated reimbursements for medical expenses, and found that a subsidiary of UnitedHealthcare was unfairly lowering reimbursements to providers and charging individuals the difference. So Cigna contracted with an external company MultiPlan so they would not be determining reimbursements internally.

If a major insurer processed claims from employer health plans using FAIRHealth, they collected no additional fee. But insurers who worked with MultiPlan typically received 30 – 35% of the difference between the billed amount and the amount that the insurer paid. While FAIRHealth charged a flat fee for their services, MultiPlan charged a percentage of the “savings” that they recommended. And MultiPlan charged very high fees to the insurers; in 2016, Cigna paid MultiPlan $500,000, while their 2019 payments amounted to $2.6 million.

The amount of money that MultiPlan and insurance giants have extracted through this process is very troubling. For example, MultiPlan informed its investors that in 2023 it had identified some $23 billion in bills that it recommended not be paid. As an example, eight California addiction treatment centers received $2.56 million from Cigna, while MultiPlan was paid $1.22 million and Cigna itself received $4.47 million for those transactions. In one specific case an outpatient substance abuse facility was reimbursed $134.13, while MultiPlan pocketed $167.48 and Cigna received $658.75. MultiPlan has agreements with some insurers where they use a practice called “meet or beat.” The insurer gives the maximum amount that they will reimburse a provider; MultiPlan then collects a fee only if the reimbursement it calculates is lower than the insurer’s maximum. Clearly, such agreements provide both MultiPlan and the insurance giants with a significant incentive to make reimbursements to providers as low as possible. It should also be noted that when insurers offer providers “low-ball” reimbursements, the providers may pass the additional costs to individuals who must then pay the bills out of pocket.

Will these revelations have any effect on the penetration of private equity into healthcare? We are doubtful about this. Private equity firms have made lavish contributions to political campaigns. One can assume that these contributions are designed to induce politicians to support the actions of private equity firms. It would be wonderful if our representatives were able to curb some of the worst excesses of private equity, particularly in the field of healthcare. In the healthcare field, the aims and actions of private equity firms are completely contrary to the goals of healthcare systems. Private equity groups saddle the firms they acquire with enormous debt in leveraged buyouts; they compound this debt with debt recapitalization schemes; furthermore, they may sell off real estate owned by the healthcare firms, requiring them to lease back properties they formerly owned. After that, private equity typically fires a significant number of staff, and encourages practices that greatly increase the cost of medical care. A significant number of healthcare companies taken over by private equity declare bankruptcy. It would seem that a strong case could be made to prohibit private equity companies from taking over healthcare organizations.

Michael O’Riordan, Physicians (Mostly) Negative on Private Equity in Healthcare, TctMD.com, Mar. 13, 2024 https://www.tctmd.com/news/physicians-mostly-negative-private-equity-healthcare

Michael DePeau Wilson, Most Physicians Down on Private Equity in Healthcare, Medpage Today.com, Mar. 11, 2024 https://www.medpagetoday.com/special-reports/features/109108

Jennifer Henderson, Senate Hearing Tackles Private Equity’s Impact on Healthcare Amid Steward Saga, Medpage Today.com, Apr. 3, 2024 https://www.medpagetoday.com/washington-watch/washington-watch/109488?xid=nl_mpt_investigative2024-04-10&eun=g1961082d0r&utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=InvestigativeMD_041024&utm_term=NL_Gen_Int_InvestigateMD_Active

Chris Hamby, Health Insurers’ Lucrative, Little-Known Alliance: 5 Takeaways, New York Times, April 7, 2024 https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/07/us/health-insurance-medical-bills-takeaways.html

Chris Hamby, Insurers Reap Hidden Fees by slashing Payments. You May Get the Bill, New York Times, April 7, 2024 https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/07/us/health-insurance-medical-bills.html

Welcome to FAIRHealth, https://www.fairhealthconsumer.org/

Update posted Jan 17 2024: A recent study was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association that studied the effects on US hospitals when they are acquired by private equity firms. The paper looked at outcomes for 662,095 patients at 51 hospitals that had been acquired by private equity firms, and compared those with outcomes for 4,160,720 patients at a control sample of 259 hospitals. The study utilized data from hospitals using 100% Medicare Part A claims. The events were chosen for 3 years prior to acquisition by private equity, and 3 years after the hospitals were bought by private equity firms.

Some of the outcomes were as follows. Medicare patients who were admitted to hospitals owned by private equity experienced a 25.4% increase in conditions acquired while they were hospitalized; major drivers of this increase were a 27.3% increase in falls and a 37.7% increase in central line-associated bloodstream infections. The report said that “Surgical-site infections doubled from 10.8 to 21.6 per 10,000 hospitalizations at private equity hospitals despite an 8.1% reduction in surgical volume. Meanwhile, such infections decreased at control hospitals, though statistical precision of the between-group comparison was limited by the smaller sample site of surgical hospitalizations.”

The study concluded that “Shifts in patient mix toward younger and fewer dually eligible beneficiaries admitted and increased transfers to other hospitals may explain the small decrease in in-hospital mortality at private equity hospitals relative to the control hospitals, which was no longer evident 30 days after discharge. These findings heighten concerns about the implications of private equity on health care delivery.”

The JAMA study validates the concerns we raise in this post regarding the effects of private equity acquisitions of hospitals and other health-care companies. In this post, we study many different companies that were taken over by private-equity firms. However, health-care firms such as hospitals, retirement homes, and group practices such as dental firms and emergency room staff all tend to experience decreased standards of care and increases in more aggressive billing practices and unnecessary costly tests, after being purchased by private equity companies. In an opinion column in the Washington Post Ashish Jha, dean of the School of Public Health at Brown University, concludes that private equity control leads to decreases in staffing levels at these facilities, combined with a reduced focus on patient safety that leads to an increased risk of harm for patients.

Dr. Jha does not recommend a ban on private equity in health care, because such firms are not the only bad actors in the field of health care. Here we disagree with Dr. Jha. In our opinion, the effects of private equity acquisition on health care outcomes are dire. The model for private equity takeovers is to slash staffing and to load the debt required to finance the acquisition onto the firms being taken over. The combination of increased debt and decreased staffing basically insures that these firms will not be able to continue providing the same standard of care to patients. In addition, the crushing debt burden incentivizes these health-care facilities to increase their revenue. Often, this is done by gaming the system, by billing for unnecessary expensive tests and procedures. In some cases, firms even billed for procedures that were never performed! We would propose that private equity firms be forbidden from acquiring businesses in the field of health care, on the grounds that the goals of private equity are contrary to the mission of health care businesses. We hope that, after reading this post, you agree with us.

Source Material:

Sneha Kannan, Joseph Dov Bruch and Zirui Song, Changes in Hospital Adverse Events and Patient Outcomes Associated With Private Equity Acquisition, Journal of the American Medical Association 330, 2365 (2023).

Stehpanie Sucheray, Study: Hospitals owned by Private Equity Firms See More Adverse Events, CIDRAP: University of Minnesota, Dec. 28, 2023

Ashish Jha, Opinion: Private Equity Firms are Gnawing Away at U.S. Health Care, Washington Post Jan. 10, 2024

September 12, 2023

I: Private Equity in America

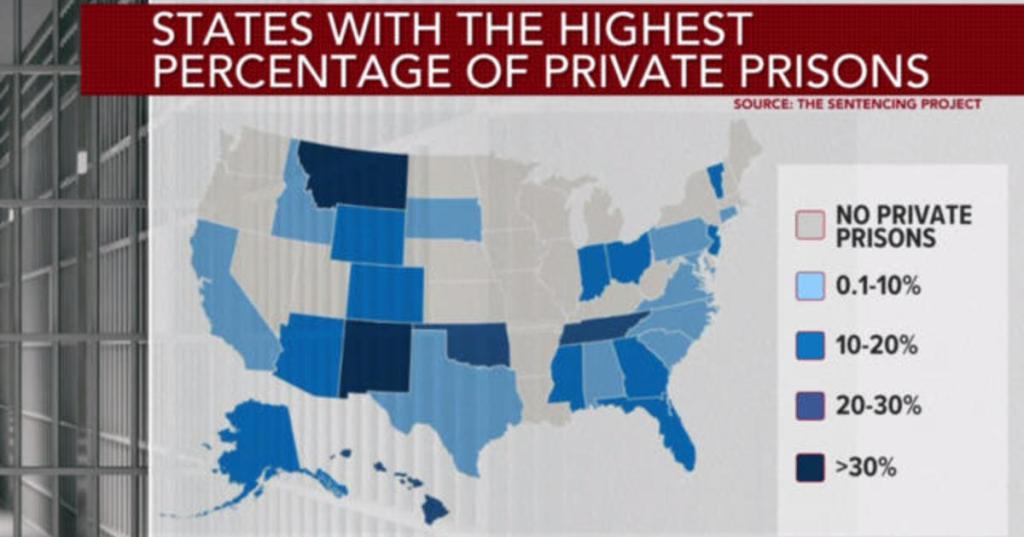

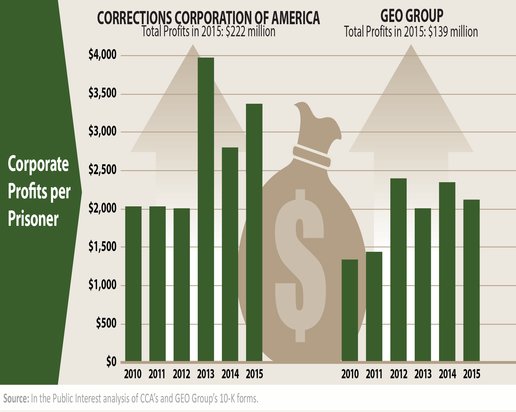

Private equity firms have established themselves in an ever-growing list of companies and services in America. They are playing a major role in our economy, and in our lives. Although many Americans don’t realize it, private equity (PE) firms own a vast array of businesses. This includes retail stores, companies that provide short-term loans, nursing homes, municipal services, chains of healthcare practitioners, hospitals, prisons and much more. In this post, we will set out the basic economics of private equity firms. Private equity firms claim that they make money because they are great money managers and that they improve the efficiency and productivity of companies that they acquire. However, many of the actions taken by private equity are destructive and produce some very adverse results. We will focus on those aspects of private equity that are destructive to the functioning of our economy. Firms acquired by private equity have been saddled with enormous and crushing debt; in many cases this debt has forced businesses into a destructive spiral that ended in bankruptcy. Along the way, these firms have laid off workers and/or cut their pay and benefits. In addition, firms are incentivized to ‘game’ the system by raising prices, cutting services and engaging in deceptive practices.

In some areas, private equity financing has led to positive outcomes. We will not review those successes in this post – you can easily discover them by reading the summaries posted by private equity firms, such as Blackstone, the Apollo Group, Kohlberg Kravis and Roberts (KKR), the Carlyle Group, or other private equity companies. In Section II of this post we will discuss the basic business model of private equity with two examples – Toys “R” Us and the Noranda Aluminum smelting company. We will demonstrate how private equity financing impacted a retail sales business, and a company in the extraction business. In both of these cases, we will show that private equity firms are able to game the system to their advantage even when the firms that they take over go bankrupt – which occurs more commonly in companies owned by private equity than other comparable companies that are publicly owned, or that are managed by the government.

In Section III of this post we will examine the role of private equity in healthcare. We will show that these firms have made great inroads in such areas as nursing homes, ambulance services, and staffing of medical specialties such as emergency room physicians, anesthesiologists, and radiologists. Private equity has also bought up chains of health care providers such as dental practices and dermatologists; and it has also bought up chains of hospitals. We will show that the ”rolling up” of chains of medical service providers by private equity companies reduces competition and decreases the number of independent providers. In addition, many of the companies acquired by private equity are responsible for “surprise billing” tactics that have a severe impact on low-income workers. Also, healthcare companies owned by private equity seem to generate more complaints of improper or even illegal billing practices.

The material in this post has been inspired by two recent books on private equity. The first is Plunder: Private Equity’s Plan to Pillage America, by Brendan Ballou. The cover of this book is shown in Figure I.1. The second is These Are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs – and Wrecks – America, by Gretchen Morgenson with Joshua Rosner. This is shown in Figure I.2. The word “plunder” in these book titles refers to the operations of private equity firms; the authors of these books claim that the actions of private equity firms are analogous to a 21st century version of the pillaging of ships by pirates. Top executives at PE firms are enriched by billions of dollars, while workers at companies owned by private equity see their wages lowered and their benefits slashed, and the companies they work for are often forced into bankruptcy. Several of the examples in this post are taken from one or the other of these two books.

Figure I.1: The 2023 book Plunder: Private Equity’s Plan to Pillage America, by Brendan Ballou.

Figure I.2: The 2023 book These Are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs – and Wrecks – America, by Gretchen Morgenson with Joshua Rosner.

II: How Private Equity Investments Work

To see how private equity works and to understand the impetus behind private equity investments, we will review the actions taken with respect to two companies. The first, Toys “R” Us, was the largest American toy retailer when it was purchased by private equity. The second is Noranda Aluminum, a large aluminum smelting company located in New Madrid, Missouri.

To understand why government has not taken a firm stand against the excesses of private equity funding and the dire consequences of some of their actions, one only has to look at the actions taken by private equity to maintain their practices. First, private equity firms have given over $900 million to federal candidates since 1990. Given this rate of political contributions, it is not too much of a stretch to say that the private equity firms have bought representatives. A second feature is that there is a very strong revolving door whereby former politicians and government officials are hired by private equity firms. Out of a slew of politicians and government officials who moved to private equity firms, we will name just a handful. Mitt Romney actually came from private equity (Bain Capital) before he became a U.S. Senator. After his failed 2012 run for President, Romney then joined the private equity firm Solamere, where one of his sons was a co-founder of that firm. Former Speaker of the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich joined JAM Capital Partners. Tim Geithner, who was CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank and later U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, became president of the firm Warburg Pincus. Vice President Dan Quayle became chairman of Global Investments at Cerberus Capital Management. Former Secretary of State Colin Powell became chairman of the advisory board at Leeds Equity Partners. Former U.S. army general and head of the CIA David Petraeus became chairman of the KKR Global Institute. Indiana governor and U.S. Senator Evan Bayh became a senior advisor at Apollo Global Management. And the Senator from North Carolina and losing 2004 vice presidential candidate John Edwards became a senior advisor at Fortress Investment Group.

Toys “R” Us:

Toys “R” Us was a retail toy company that became the major toy superstore in the U.S. The company Toys “R” Us was founded in 1957 in Rockville, Maryland by Charles Lazarus. The company grew, prospered and expanded rapidly. Because it was an early adopter of computer inventory, it was able to rapidly understand consumer demands; this enabled it to keep the “latest craze” toys and games in stock when competitors ran out. Eventually Toys “R” Us became the largest and most profitable toy store in the U.S. The flagship Toys “R” Us store was a mammoth store in New York City’s Times Square: that store featured “an enormous indoor Ferris wheel, life-sized Barbie Dreamhouse, and twenty-foot animatronic T Rex.” Here we will review the takeover of Toys “R” Us by private equity firms, as discussed in Brendan Ballou’s 2023 book Plunder.

Figure II.1: The Toys “R” Us flagship store in Times Square, New York City. The store closed in 2017 when the toy company, owned by a group of three private equity firms, declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

In 2005, Toys “R” Us was purchased by a group of three private equity firms – Bain, KKR and Vornado. At the time of purchase, Toys “R” Us had over $2 billion in cash and other assets. The firms paid a hefty $6.6 billion for the company. However, neither the private equity firms nor their investors put up all that money – they contributed only $1.3 billion of the purchase price. The remaining $5.3 billion became debt that was not assumed by the private equity investors but was loaded onto Toys “R” Us. An important aspect of private equity is that it strives to extract the maximum amount of profit from its investments in the shortest possible time. By dumping the massive debt onto Toys “R” Us, the firms greatly decreased the amount of money they would have to borrow in order to recoup their $1.3 billion investment.

For Toys “R” Us, however, that debt became a millstone around their neck; the interest payments alone on that debt amounted to nearly $500 million per year. In addition, the private equity firms charged the toy company millions of dollars in fees – a fee for the initial purchase; yearly management fees; fees for the debt accrued by private equity; and several other fees. Toys “R” Us subsequently bought other toy firms, including FAO Schwartz and the assets of K-B Toys. By the way, K-B toys was a firm that had been taken over by Bain Capital and then gone bankrupt. Since Bain was one of the private equity backers of Toys “R” Us, there was a whiff of self-dealing in this purchase. In fact, critics of private equity have alleged that private equity firms undervalue the firms that they purchase. In some cases, as was the case with K-B Toys, this is because a group of investors purchases a company owned by some of their own investors. In other cases, critics allege that private equity firms often refrain from competing with one another for the companies that they purchase, thus allowing businesses to be purchased for relatively small amounts. The private equity firms charged Toys “R” Us transaction fees for those purposes; those transaction fees added up to more than $100 million. The private equity firms owned Toys “R” Us for 13 years, and in that time the Private Equity Stakeholder Project estimates that the company paid the three private equity firms $464 million in fees.

The private equity firms also withdrew cash and assets from the toy store at regular intervals. By 2017, the company had only 15% remaining of its initial $2 billion in assets. So Toys “R” Us embarked on a number of cost-cutting measures. They slashed the staff and cut pay and benefits for the remaining workers. They cut back on maintenance – activities such as cleaning the stores, sweeping the parking lot, and maintaining the infrastructure were all reduced. The trademark glamour of Toys “R” Us stores was replaced by shabbiness. Even worse, the company cut back on its computing costs, so they lost their advantage in maintaining stocks of popular toys. Hobbled by the crushing debt and the hefty management fees imposed by the private equity firms, Toys “R” Us eventually declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2017.

Note that Toys “R” Us was cutting back on the number of employees and slashing their pay and benefits while private equity principals were making millions of dollars off the company. The co-founders of private equity firms have become some of the richest men in America: the co-founders of KKR, Apollo and Blackstone are currently worth $7 billion, $9 billion and $29 billion, respectively. Furthermore, while Toys “R” Us personnel were being laid off, CEO David Brandon, an ally of the private-equity firms, was being compensated on a grand scale. While the 90th percentile of toy store CEO salaries was $1.56 million/year, Brandon was paid $3.75 million. And when the company’s lawyers informed him that his bonus would likely be cancelled once the firm declared bankruptcy, Brandon ordered that the company provide him with a $2.8 million bonus, with similar bonuses for other top company executives, three days before the firm declared bankruptcy. Brandon had promised Toys “R” Us staff that they would receive severance pay amounting to $80 to $100 million in returning for working through the holiday season, but one week later he withdrew that offer, and company workers received only $2 million, which amounted to $60 per employee. Brandon also assured company staff that “there have not been – nor will there be – any bonuses paid to executives or anyone else given the current financial condition of our company.” According to lawsuits filed against the company, this was a flat-out lie by Brandon.

Even in the bankruptcy proceedings, Toys “R” Us was fleeced by the private equity firms. Toys “R” Us had declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy, rather than Chapter 7 bankruptcy. In the former case, a company discharges some of its debt while continuing to operate; the purpose is to gradually pay off the debts and becoming solvent. In Chapter 7 bankruptcy, the company is shut down and its remaining assets are sold to its creditors. However, during the bankruptcy process the hedge fund Solus Capital Management, which held a substantial amount of the Toys “R” Us debt, collaborated with four other debt holders to force the company to liquidate and sell off its assets. This caused 33,000 Toys “R” Us staff to lose their jobs, but Solus made money off the resulting fire sale of assets.

Figure II.2: The Toys “R” Us bankruptcy filing, from a Wall Street Journal article.

So, in 13 years the private equity firms had taken the most profitable toy store in America and pushed it into bankruptcy. And the problem was not competition with Amazon, as the private equity firms alleged. In the year before the takeover, Toys “R” Us had generated $11.1 million in sales. In the year before declaring bankruptcy, Toys “R” Us had $11.2 billion in sales, which amounted to 20% of all toy sales in the U.S. However, by 2017 the company had $460 million in operating profit and $457 million in debt payments. This left essentially nothing to pay for staff salaries and building maintenance. KKR claimed that it lost millions of dollars in the Toys “R” Us fiasco. However, Dan Primack of Axios calculated that, due to the hundreds of millions of dollars paid to the private equity firms in assorted fees, the private equity firms had actually made a profit. The net result was devastating to Toys “R” Us staff. And yet, the private equity firms apparently made money by driving the company into the ground.

Bankruptcy is a common outcome of private equity takeovers. In the years 2016 and 2017, two-thirds of the retailers that filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy were backed by private equity. A 2019 study by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project found that over the preceding decade some 600,000 people had lost their jobs as a result of bankruptcies in retail firms that had been taken over by private equity. As a result, an Atlantic Monthly story about private equity financing in the retail industry was titled “You Buy It, You Break It.”

Noranda Aluminum:

The story of private equity and the Noranda company was discussed by Gretchen Morgenson in her book These Are the Plunderers. Noranda Aluminum was a large aluminum smelting company located in New Madrid, Missouri. Most of the alumina used in smelters was imported from Mexico and could easily be shipped up the Mississippi River to the Noranda location. Noranda’s smelter produced 15% of the U.S. supply of aluminum, and it was the largest employer in New Madrid. Many of Noranda’s customers were located in the region, so the bulk of its production could be delivered within a day. In addition, Noranda had a long-term contract with its Missouri power company, which guaranteed a stable source of low-cost energy. Before its purchase by Apollo in 2007, Noranda Aluminum had experienced growth of 5% per year since 2000.

Figure II.3: The Noranda Aluminum smelter on the banks of the Mississippi River outside New Madrid, Missouri.

Noranda dominated the New Madrid economy; it produced one-quarter of the county tax revenues and provided one-third of the revenue for the local school district. Perhaps more importantly, it provided well-paying jobs to 900 members of the community. The major private equity firm Apollo bought Noranda in 2007 for $1.15 billion. Of that amount, $214 million was provided by Apollo and its investors, and the remaining $1 billion was debt that was assigned to Noranda Aluminum. Apollo appointed Kip Smith as Noranda’s CEO. He assured the community that Apollo was in it for the long haul: “We want a company that not only achieves success in the short term but will also be here in 100 years – to provide high-quality manufacturing jobs for several generations to come.” These were very welcome words to the citizens of Missouri – we will see whether Apollo lived up to its commitment.

Just three weeks after purchasing Noranda Aluminum, Apollo carried out a ‘dividend recapitalization’ that added $220 million to Noranda’s already mushrooming debt. Was that money used to provide capital to Noranda? No, it was absorbed by Apollo. So only three weeks after purchasing the aluminum smelter, Apollo had already recouped 100% of the money it raised for the purchase! Such dividend recapitalizations became a common theme in the private equity community. In 2007, private equity companies raised $20 billion through dividend recapitalization schemes. If those funds were wisely re-invested in the companies that had been purchased, it is possible that they could be an asset for those companies. But when the additional debt heaped on the company was simply used to line the pockets of the Apollo executives and their investors, this only added to the crushing weight of the debt being carried by companies such as Noranda. And Apollo was particularly active in carrying out dividend recapitalization schemes: a report from Moody’s Investor Services found that between 2009 and 2017, Apollo had initiated such schemes within a year of purchase for two-thirds of the firms it took over.

The net effect of the Apollo takeover plus the dividend recapitalization left Noranda consumed by debt. Before being taken over by Apollo, Noranda had $151 million in long-term debt. A month after the takeover, Noranda’s debt was $1.15 billion. In addition, Apollo charged Noranda a fee for the cost of being taken over by private equity! Moreover, in June 2008 Apollo sucked another $101 million from Noranda in fees for managing the company. Not surprisingly, the combination of debt plus fees proved ruinous to Noranda. In 2007, for the first time in its history, the company reported a loss of $74 million.

Apollo continued to bleed Noranda dry. In 2012, the company issued another $550 million in debt, while Apollo took $54 million in cash. In that same year, Apollo sold some of Noranda’s shares to the public, netting $108 million in the transaction. And that money went – you guessed it — to Apollo. Over a five-year period, Apollo had taken $400 million in dividends from Noranda and another $13 million in fees. At the same time, they were slashing jobs at the smelter. And Apollo was pressing the state of Missouri to obtain a $25 million reduction in their energy bill – an amount that would have to be absorbed by private customers if approved. Eventually Apollo prevailed on that request.

In April 2015, following a $250,000 contribution to politicians in Missouri, coupled with the threat that Apollo might shut down the Noranda smelter, Missouri’s Democratic governor and Republican lieutenant governor pressured the state’s public service commission to grant Noranda the $25 million rate reduction. But one month later, Apollo sold off all of its stock in Noranda (none of that revenue went to the aluminum smelter). With the stock hovering near zero, Noranda announced in February 2016 that it was closing the smelter, declaring bankruptcy. The company’s employees were all laid off, and the taxes from Noranda vanished from the county payroll. As a final slap in the face, Noranda defaulted on the $3.1 million it owed the New Madrid County School District. The company’s assets and the smelter itself were sold to Swedish and Swiss companies. The smelter has finally re-opened in 2023.

In just nine years since the Apollo takeover, Noranda was bankrupt. All of the jobs at the smelter were lost, in addition to the loss of millions of dollars in tax revenue. When Noranda went bust its pension plans also collapsed, as Apollo left the Noranda pension plans underfunded by $219 million. This money had to be supplied by the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation (PBGC). This means that the U.S. taxpayers had to subsidize the underfunded pension plan. The Noranda takeover was a disaster for the citizens of New Madrid and the state of Missouri. However, the Noranda deal was a major generator of profits for Apollo. Despite the bankruptcy, Apollo recouped three times the money that it had initially invested in the company. This resulted in a transfer of hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars to Apollo CEO Leon Black and his billionaire colleagues.

From the two examples of Toys “R” Us and Noranda Aluminum, we see the private-equity model of finance. Companies are purchased with the private equity firm and its investors putting up only a fraction of the purchase price. The remainder of the purchase is generally piled onto the purchased company, leaving it with a massive debt that needs to be repaid. Often, payment on that debt puts the company in the red. But this is just the beginning. The private equity firm also assesses massive fees on the company, from a transaction fee for the cost of the takeover to management fees for the company. If the acquired company purchases other firms, the company is charged additional fees for those takeovers. And “dividend recapitalizations” may load even more debt onto the company.

The huge debt incentivizes the company to take severe steps. Often the takeover is followed by massive layoffs of personnel, and reductions in pensions and benefits. In many cases, the result is the bankruptcy of the acquired company. However, even in these circumstances the private equity firm can reap benefits – in the case of Noranda, Apollo made three times the purchase price of the company before it declared bankruptcy. Figure II.4 is a cartoon “The House Never Loses,” that shows the corporate model for private equity, and how it makes money at every stage of a company after a takeover, even if the firm goes bankrupt.

Figure II.4: A cartoon, “Private Equity: the House Never Loses.” It shows how private equity firms make money at every stage following a takeover, even if the firm goes bankrupt.

III. Private Equity in Healthcare

Healthcare is one of the most active areas that private equity has invested in. In 2006, health care expenses in the U.S. amounted to 16.5 percent of gross domestic product. And this figure could be expected to increase as the American population continued to age and government contributions to health care kept rising. Private equity seized on opportunities to “roll up” different segments of health care. One of the first forays of private equity into health care was in 1998 when Apollo Capital Management purchased two nursing home chains, GranCare and Living Centers of America, and merged them. Since then, private equity firms have expanded their reach into many different aspects of health care. In this section we will review the impact of private equity firms on a number of different aspects of health care. We will discuss private equity investments in chains of nursing homes, in services such as ambulances and emergency rooms, in chains of health care practices such as dermatology and dentistry, and in hospitals. In all cases we will show that investment by private equity leads to significant deterioration in the quality of care, together with increases in costs to patients and apparently also in increases in deceptive practices by these companies.

Nursing Homes:

In earlier sections we have shown that the goals and actions of private equity are often in conflict with our desire for a stable and equitable economy. However, when private equity enters the field of American healthcare the disconnect between the actions of private equity firms and the public welfare is particularly glaring. While the goal of private equity firms is to maximize their short-term profits, the goal of healthcare is to provide quality medical care to patients at affordable prices and to provide long-term stability. As an example of the pernicious role of private equity in healthcare, we will review the takeover of the nursing home chain HCR ManorCare by the private-equity Carlyle Group, as documented by Brendan Ballou in his 2023 book Plunder, and also covered by Gretchen Morgenson and Joshua Rosner in their 2023 book These Are the Plunderers. We will show how the actions of Carlyle led to serious degradation of the quality of health care at HCR ManorCare, and the eventual bankruptcy of that company.

Nursing homes are the descendants of almshouses and old-age homes that were often run by charities or churches. In the U.S., nursing homes expanded greatly when the Medicare and Medicaid Acts of 1965 authorized direct payments to old-age homes that provided medical care for the aged. A successful nursing home will provide stable, quality healthcare to senior citizens. Nursing-home conglomerates developed in the 1990s, when large corporations bought up individual homes. When it was purchased by the Carlyle Group in 2007, HCR ManorCare was quite successful. It was the second-largest nursing home chain in the United States, and it had historically catered to senior citizens who were not reliant on Medicare or Medicaid for their payments. In 2007 HCR ManorCare was a profitable business.

Figure III.1: HCR ManorCare. When the private equity Carlyle Group purchased ManorCare in 2007, it was the second-largest nursing home chain in the U.S. Just 11 years later it declared bankruptcy.

The Carlyle Group purchased HCR ManorCare for $6.1 billion. Of this amount, $1.3 billion was provided by Carlyle and its investors, while the remaining $4.8 billion was debt that was transferred to ManorCare. At the time of the takeover, ManorCare owned all of its 500 nursing homes. But in 2011, Carlyle sold 338 of ManorCare’s nursing homes to the real estate investment firm HCP for $6 billion. This so-called sale-leaseback arrangement meant that the Carlyle Group had recouped all of its investment in HCR ManorCare. The bulk of the profits from the sale went back to the Carlyle Group. However, for the nursing-home conglomerate this was a dire blow – it meant that the nursing-home company now had to rent most of the facilities it was currently using and had previously owned. One term of the sale-leaseback arrangement was that the rental payments increased by 3.5% each year; eventually this cost ManorCare $500 million a year in rent. Furthermore, the deal was structured in such a way that ManorCare, and not the new property owners, still had to pay for the taxes, upkeep and insurance on those homes. In other words, ManorCare was now saddled with all of the costs of maintaining its properties, plus the costs of renting them from their new owners.

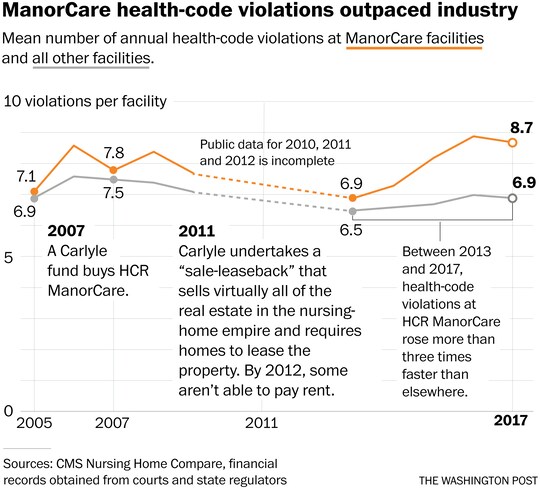

In addition, the Carlyle Group assessed ManorCare with a $67 million transaction fee for the cost of being purchased by Carlyle. Over a nine-year period, Carlyle also charged ManorCare $27 million in ‘advisory fees.’ Not surprisingly, these enormous new costs, plus the debt that Carlyle heaped on ManorCare, meant that the nursing-home chain rapidly became unprofitable. As a result, ManorCare was forced to lay off a significant number of its nursing staff, and it also instituted a number of cost-cutting efforts. For example, between 2010 and 2014 ManorCare decreased its budget for facilities by 6%. As the staff were responsible for providing decent medical care to ManorCare’s residents, one could predict that cutting the staff would degrade the quality of nursing-home care, and this is exactly what happened. Figure III.2 compares the mean number of health-code violations at ManorCare facilities with those from all other nursing homes, as calculated reporters in a Washington Post exposé of the ManorCare saga. From 2013 to 2017, the number of health code violations increased by 26%; this was three times greater than the increase in health-code violations at all other nursing home chains during this period.

Figure III.2: Comparison of health-code violations at ManorCare with all other nursing home facilities in the period 2005 – 2017. Between 2013 and 2017, health-code violations at ManorCare rose more than three times the rate at all other nursing homes.

By 2018, HCR ManorCare was more than $6 billion in debt. In just 11 years since its purchase by Carlyle, ManorCare had been transformed from a healthy profitable business to one that was hopelessly in debt. Despite the drastic staff reductions and the cost-cutting measures, ManorCare was forced to declare bankruptcy, and was then purchased by a non-profit group. The accrued debt in this transaction had been transferred from Carlyle to ManorCare, so for Carlyle this debacle was considered a success. The ‘sale-leaseback’ arrangement was particularly dire for ManorCare. Obviously, it made no sense for the nursing-home company to sell most of its own facilities and then rent them from the new owners, while continuing to bear the costs of taxes and maintenance. The transfer of debt from Carlyle to ManorCare, plus the profit from selling the nursing-home properties, proved fatal to ManorCare, but was viewed as a financial coup for Carlyle.

So let’s re-cap this deal. In the 11 years following its takeover of HCR ManorCare, Carlyle transformed the nursing-home group from a profitable conglomerate to one that was $7 billion in debt. In addition, Carlyle had sold most of the nursing-home facilities, which forced the ManorCare staff to institute draconian staff cuts, and also to cut back on other expenditures. Finally, after laying off many of their nursing-home staff to cut expenses, at the time of the bankruptcy Carlyle awarded the ManorCare CEO Paul Ormond $117 million in deferred compensation. No wonder that Oxford professor Ludovic Phalippou concluded that “People will wonder whether this pure capitalism is appropriate in nursing homes. The health and welfare of the old people who live there depend on them.”

As we have seen, after ManorCare nursing homes were burdened with these new expenses and crushing debt, patient care suffered dramatically, and this was evidenced in several ways. First, there was the unprecedented increase in health code violations at ManorCare facilities. In 2009 a physical therapist at one of ManorCare’s facilities, Christine Ribik, filed a whistleblower claim with the federal government. Ribik claimed that ManorCare executives had pressured the therapists to provide unnecessary therapy sessions. Ribik alleged that her nursing home “had billed even medically unstable patients who were unresponsive or near death for therapy sessions.” The therapy treatment time that was billed included periods while patients were “asleep, walking to treatment, toileting or had dementia.”

Ribik also alleged that ManorCare facilities were gaming the Medicare reimbursement system. Medicare reimbursed patients for therapy on a sliding scale based on the number of therapy treatments and the amount of time spent in physical therapy. The highest Medicare reimbursement rate was “Ultra High.” But after ManorCare was purchased by Carlyle, the percentage of patients billed at the Ultra High level rose dramatically. In fact, an internal ManorCare communication to therapists mandated “Consider each patient Ultra High and work down, not up as needed” for billing purposes. In 2006, ManorCare had requested Medicare reimbursement at the Ultra High level for 39% of its patients; but by 2010 some 81% of their patients were being billed at the Ultra High level. As one example, a Muskegon Michigan ManorCare facility billed 8.4% of its rehab assignments at the Ultra High rate before the Carlyle takeover, but by Oct. 2009 they were billing 93.3% at the Ultra High rate. The Justice Department filed suit against ManorCare in 2015; at that time, they alleged that “ManorCare administrators frequently kept patients in their facilities despite recommendations from treating therapists that the patients should be discharged” [The DOJ dropped the lawsuit in 2017].

A 2021 study of nursing homes by researchers at the University of Chicago, Pennsylvania and New York University determined that “private equity ownership was associated with over 20,000 premature deaths in nursing homes over a 12-year period.” So, for the patients the role of private equity firms in nursing homes has been an unmitigated disaster. Previously profitable nursing home groups became bankrupt after purchase by private equity groups. In addition, many staff were laid off, purchases of supplies and equipment were cut back, and billing practices were adopted to game the Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement scales. A 2021 study of nursing homes by the National Bureau of Research found that nursing-home businesses run by private equity groups had death rates of their inmates that were 10% higher than other comparable nursing homes; this amounted to at least 20,000 premature deaths of senior citizens between 2005 and 2017. A 2011 study of nursing homes by the Government Accountability Office found that for-profit nursing homes (including both those run by private equity and other for-profit corporations) “had more deficiencies than non-profit facilities. Profit margins were higher in private equity-backed homes, and total nurse staffing ratios were lower than other facilities, including those operating for profit.”

We are just emerging from a three-year COVID-19 pandemic. In the early stages of this pandemic, before vaccines were available, there were widespread shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) for hospital and nursing-home staff. In addition to helmets, gloves, face shields, goggles and facemasks, there were serious shortages of respirators and ventilators. But it was no surprise that these life-saving devices were in short supply. As early as 2006 the federal government, private firms, and the military had all run pandemic simulations; these invariably showed that health-care facilities had inadequate supplies of PPE. Reports strongly urged that medical facilities stock up on PPE supplies. Unfortunately, these recommendations were ignored for the most part, leading to unnecessarily large waves of deaths in the early stages of the pandemic. Shortages of PPE supplies occurred not only in firms owned by private equity but were experienced in all sectors of health care. However, medical facilities purchased by private equity firms would be particularly unlikely to stock up on PPE essentials before a pandemic struck. Such facilities would be burdened with crushing debt, and their governing boards would be focusing on short-term triaging rather than long-term planning.

The purchase of ManorCare was a disaster for the nursing home industry, for medical staff who were laid off or pressured to adopt billing scams to bilk Medicare, and for the nursing home patients who died at greatly increased rates in facilities owned by private equity. Nonetheless, the purchase and subsequent history of HRC ManorCare was heralded as a great success of private equity. Carlyle made back over 100% of its purchase price within a few years of the acquisition. Plus, the hefty management fees levied by Carlyle brought in even more revenue to the private equity firm. However, it is hard to imagine a worse fit between the goals of private equity firms and those of nursing homes. Private equity focused on extracting the maximum profit from a company in the shortest time. In the case of ManorCare, this involved selling off most of the properties owned by ManorCare, and by making massive cuts in the nursing home staff.

Private Equity in Ambulance and Emergency Room Services:

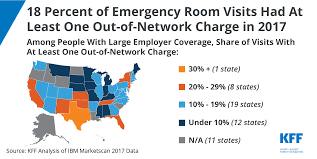

Since the financial crisis in 2008, private-equity firms have increasingly invested in many of the civic services that were formerly provided by state and local government. In the field of healthcare, two areas where private equity has been particularly active are ambulance services and the staffing of emergency room physicians. In these two areas, the role of private equity has expanded dramatically. Figure III.3 shows the percentage of times that a patient is likely to receive a “surprise bill” for a medical event. “Surprise billing” is a phenomenon where an insured patient contracts for a medical service in their insurance network, but finds out that their provider is out of network. In those instances, the patient may find that their insurance covers only a fraction of the “in-network” costs of the service; in the most dire circumstances, the insurance may refuse to cover the cost of the service altogether. When surprise billing occurs, the patient is generally dealing with a hospital or medical service that is in their network; however, one or more of the providers of care is an independent staffer not connected to the network. In the case of ambulance services, generally a patient will contact an ambulance without checking whether the company is licensed by the municipality, or whether it is a private company.

In a substantial number of cases, surprise bills arise when private equity firms buy up ambulance services, or they contract with groups of doctors in particular specialties. Some of the most common practices where private equity has invested are emergency medicine, anesthesiology and radiology. Private equity firms have become notorious for creating situations that result in surprise billing. Figure III.3 shows that air ambulance services are likely to generate surprise bills in over 2/3 of such services, and ground ambulance services will generate out-of-network bills half the time.

Figure III.3: The percent of visits that result in a likely “out-of-network” bill from the provider. In these circumstances, it is highly likely that the firms or the individuals are controlled by private equity firms. Over 2/3 of air ambulance services and half of ground ambulance services are likely to generate out-of-network bills, and about 20% of emergency department personnel may be out-of-network.

As we have shown, private equity firms are focused on extracting as much money as possible in the shortest time. In addition to loading a purchased firm with debt to finance the acquisition, private equity firms also often increase costs, cut staff and decrease salaries and benefits for their employees. A New York Times study of emergency services such as ambulance companies and fire departments that were backed by private equity found some disturbing results. Of twelve ambulance companies that were owned by private equity in the Times study, three had recently filed for bankruptcy, while none of the ambulances operated by municipalities went bankrupt. Furthermore, companies owned by private equity performed poorly in a number of categories including response times and the reliability of devices such as heart monitors.

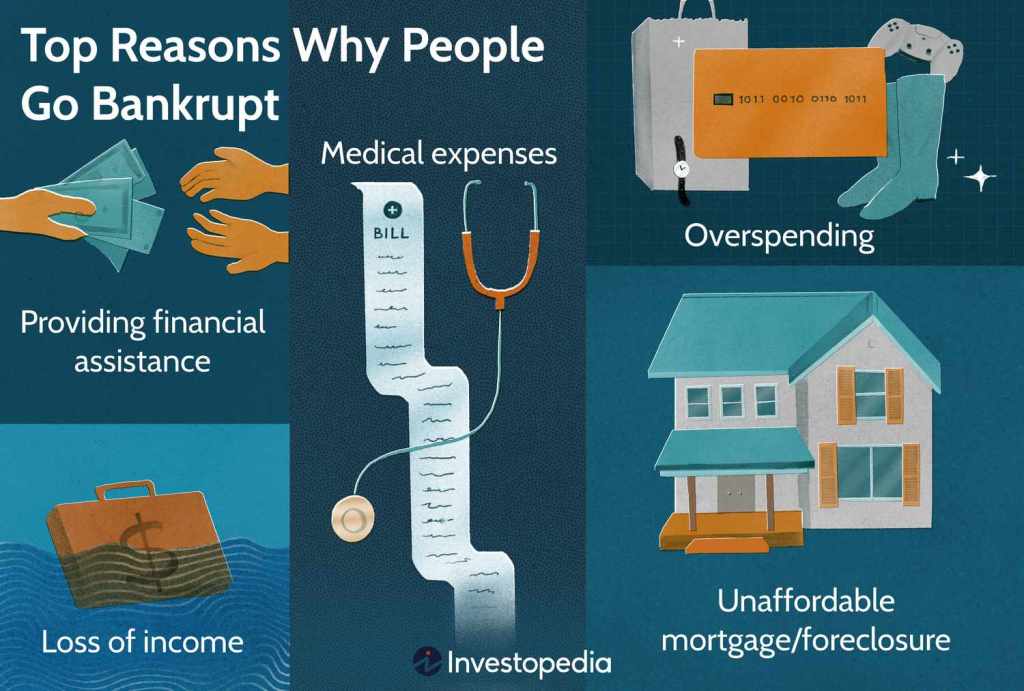

Figure III.4 shows the five main reasons that Americans declare bankruptcy. The largest single reason was loss of income, and the second was medical expenses. Medical expenses are often devastating for families, particularly when the expenses turn out to be larger than expected.

Figure III.4: The top five reasons why Americans go bankrupt. Of these, “loss of income” is the most common reason for bankruptcy, while “medical expenses” are the second highest.

Figure III.5 shows the concerns about seven types of expenses faced by families. The #1 concern on this list was “unexpected medical bills.” Two-thirds of the respondents were “very worried” or “somewhat worried” about medical bills. One significant contributor to this concern is “surprise medical bills,” where individuals find that their co-pays are greatly increased, or their claims are denied altogether, when they go to a hospital or medical practice in their insurance network, only to find that individual staff do not participate in that network. Private equity makes a significant contribution to “surprise bills.” They have bought up chains of practitioners in medical specialties such as emergency room physicians, anesthesiologists, radiologists and other medical staff. The staff belong to these groups, and private equity firms purchase companies that provide hospitals and medical services with staff. The staff are employed by these institutions, but they often are not members of the hospital network. As a result, the bills they submit are only partially covered by insurance, leaving the patient with a large co-pay; or the insurer may decline to cover any of this cost, requiring the patient to shoulder the full cost of treatment. Businesses owned by private equity are also more prone to take patients to court when they are unable to afford such “surprise” bills.

Figure III.5: Public concerns about various costs to families. Of the seven categories listed here, “unexpected medical bills” was the top concern, with two-thirds of the respondents reporting they were “very worried” or “somewhat worried” about these medical costs.

An East Coast ambulance service called TransCare manifested some of the worst features of private equity ownership. In 2003, TransCare had been owned by a private equity firm and declared bankruptcy. At that point the company was purchased by private equity firm Patriarch Partners. Initially the company appeared to be on solid footing, but financial issues soon emerged. The company began to accumulate health-department violations for failed ambulance inspections. Some employees reported that their company cut back so drastically on funds for medical supplies such as medications and sanitary wipes that they were forced to steal supplies from hospitals after they discharged a patient; other employees reported that TransCare ambulances carried expired meds. Employees also alleged pressure from their parent company to transport patients unnecessarily in their company’s ambulances. Employees described driving ambulances on 911 calls when the brakes were not working properly.

As TransCare’s financial situation worsened, it raised prices in an attempt to cover its costs. This meant that more people were unable to pay the hefty ambulance bills. The company then stepped up its bill-collection efforts; and when people were unable to pay they were taken to court. In February 2016, TransCare shut down abruptly, with no warning, and filed for bankruptcy. On that date, more than 30% of their vehicles were out of service. Figure III.6 shows an employee of TransCare attempting to enter the company’s building on the day that TransCare declared bankruptcy and abruptly closed all their offices.

Figure III.6: An employee of TransCare private-equity ambulance service attempting to enter the company’s building on the day that the firm declared bankruptcy and abruptly closed all their offices.

Private Equity in Healthcare Practices:

Private equity firms have been spending enormous amounts of money to purchase companies that deal with all aspects of healthcare in the U.S. In the year 2021 alone, the total amounted to $150 billion. Brendan Ballou reports that “by buying and combining competitors, firms have been able to raise prices, lower pay for employees, and decrease the quality of care for patients.” One area where this has been especially prevalent is the purchase of firms that place medical specialists in hospitals.

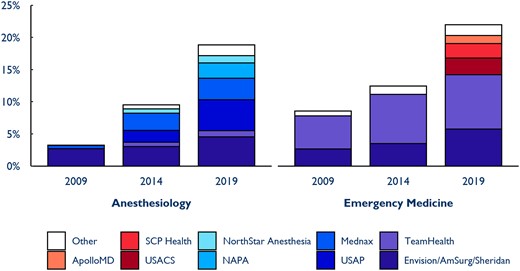

Another area where private equity firms have been particularly active is the purchase of chains of medical specialty clinics. Among these are pediatrics, dental care, dermatology, urgent care and mental health. The Brookings Institute estimates that in just over a decade, private equity firms have bought over 1,200 clinics in the U.S. Globally, private equity firms have spent more than $500 billion buying up healthcare companies in the past decade. Figure III.7 shows the share of the U.S. market for anesthesiologists and emergency room physicians who work in firms controlled by private equity. Those numbers have risen from 4% for anesthesiologists and 9% for ER physicians in 2009 to 20% of anesthesiologists and 23% of ER doctors in 2019. In this post we will discuss the impact of private equity on two of these fields: dermatology and dentistry.

Figure III.7: The penetration of private equity into the fields of anesthesiology and emergency medicine. The figure shows eight firms owned by private equity and the percentage of all such firms from 2009 to 2019. In 2009, only 4% of anesthesiologists and 9% of ER doctors belonged to firms owned by private equity; by 2019 20% of anesthesiologists and 23% of ER doctors belonged to such firms.

Heather Perlberg of Bloomberg Businessweek reported on the purchase of the dermatology chain Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery by the private equity Audax Group. The PE model for medical practitioners works in the following way. Medical practice firms owned by private equity are structured so that the parent company “rents the office, owns the equipment, employs the staff, handles the billing and, according to insiders, sets the revenue targets. The medical staff are employed by a second affiliated company that owns the practices.” This procedure allows the private-equity firms to claim that the medical practices are “owned and governed” by the professional staff, thereby skirting state laws that require medical and dental practices to be owned and operated by professional staff. Critics of this system claim that the staff are under the direction of the private equity firms, while the PE firms deny this. The issue of who is ‘calling the shots’ in these medical-services companies has been the subject of a large number of lawsuits.

Following the purchase of Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery, the firm instituted strict limits on the purchase of supplies by doctors in this chain; one doctor reported that these limits precluded him purchasing supplies as basic as “gauze, antiseptic solution and even toilet paper.” A doctor at U.S. Dermatology Partners, another chain owned by private equity, complained that the corporate office switched to a cheaper brand of needles, “which often broke off inside patients’ bodies.” Audax also allegedly imposed a scorecard system where offices were supplied with money “when they met daily and monthly financial quotas.” At other companies, doctors were told to send patients home with open wounds, but then to schedule them to return the following day for stitches; in this way, the office could double the reimbursement they received from insurance companies. In several cases, dermatology firms owned by private equity were directed to assign more and more procedures to physician assistants rather than to doctors on their staff; the physician assistants were more likely to miss spotting possibly deadly skin cancers.

There are several major Dental-Service Organization (DSO) chains in the U.S. Nine of the ten largest DSOs and 27 of the top 30 are owned by private equity firms. A major chain of dental practices is Aspen Dental, which is owned by three private equity firms. The bulk of the chain is owned by Leonard Green & Partners and Ares Capital, with American Securities holding a smaller share. Those PE firms claimed that although they owned the practices, they were only concerned with administrative office finances and not the practice of dentistry. However, in 2015 New York state attorney general Eric Schneiderman filed suit against Aspen Dental, claiming that the private equity companies put great pressure on staff to increase sales of dental products and services. Schneiderman pointed to internal documents that demonstrated pressure on hygienists to increase the revenue they generated. Hygienists were asked “Did you offer each patient whitening? Did you make sure every patient was scheduled for recall? Did you offer MI paste as a solution to patients with sensitivity?”

Figure III.8: The dental practice chain Aspen Dental, which is primarily owned by private equity firms Leonard Green & Partners and Ares Management. The chain has been charged in lawsuits from several states, including New York and Massachusetts.

In 2022 the state of Massachusetts charged Aspen Dental Management with deceptive practices. The Massachusetts attorney general alleged that Aspen “Has cheated thousands of Massachusetts consumers through a series of bait-and-switch dental advertising campaigns in a variety of media, including online advertisements that collectively appeared millions of times, lining its pockets with millions of dollars.” During the period when Aspen has been owned by private equity, it has paid at least $1.7 million in settlements with Indiana, New York, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. However, since 2012 the three private equity firms have made at least $1.1 billion in debt-funded dividends from Aspen Dental.