July 7, 2025

I. introduction

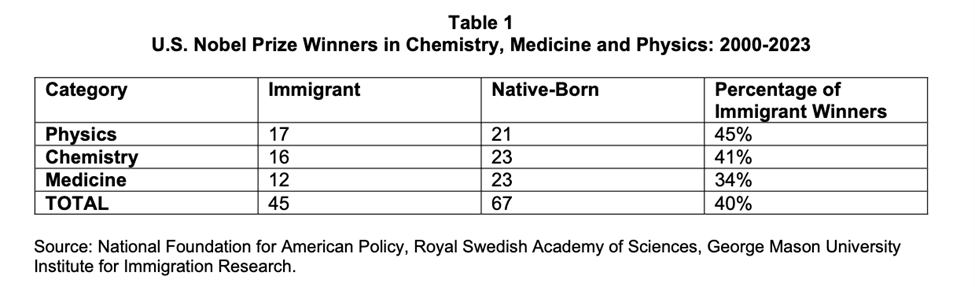

U.S. economic and geopolitical dominance since the end of World War II has been driven, in significant part, by its dominance in science and technology. One estimate is that 85% of the country’s post-war economic growth has been driven by advancements in science and technology. Those same advancements have improved our national security and transformed the daily lives of Americans. And that dominance has been critically supported by outstanding immigrant scientists. For example, during the 21st century 40% of Nobel Prizes in Physics, Chemistry, and Medicine awarded to American scientists have gone to first-generation immigrants, as summarized in Fig. I.1. That percentage is only slightly increased from the 36% of American awards given to immigrants over the full history of the Nobel Prize from 1901 through 2023. Furthermore, 43% of American workers with doctorates in science and engineering fields are currently foreign-born.

Before the rise of Hitler and the Nazi German occupation in much of Europe, the U.S. had been something of a backwater in scientific research. For centuries the most profound scientific discoveries and developments had been taking place in Europe. Think, for example, of Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo, Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, Dmitri Mendeleev, all before the 20th century. European scientific dominance continued with the revolutions in physics during the first 30 years of the 20th century – the developments of quantum mechanics and of relativity. Those developments were carried to the U.S. at first by Americans trained in European laboratories and science departments, such as J. Robert Oppenheimer. But the U.S. received a healthy portion of the scientists fleeing Hitler’s bigotry and policies, including Albert Einstein, Felix Bloch, Eugene Wigner, James Franck, Otto Stern, and other Nobel Prize winners. Several eventual Nobel Prize winners were born in pre-war Germany but emigrated to the U.S. as children with their families. As we will document in Section II, a number of the immigrant scientists who fled Nazi-occupied Europe played significant roles in the Manhattan Project that developed the U.S. atomic bomb.

After the war the U.S. made a conscious and considerable effort to continue to attract foreign scientists to train and work at its universities and research laboratories. Many foreign students and scientists came and continued to come until very recently. They were attracted by a number of features of American post-war life:

- Increased friendliness toward and welcoming policies for immigrants (updated immigration laws in 1965 and 1990);

- The stability of U.S. government and economy;

- A spirit of optimism and innovation at U.S. research institutions, buoyed by the firm establishment of academic freedom at American universities (confirmed in the 1957 Supreme Court case Sweezy v. New Hampshire);

- Healthy and sustained federal funding of scientific research;

- The outstanding reputation and strong faculties of many U.S. universities;

- The promise of attractive employment opportunities for foreign students.

Donald Trump in his second Presidential administration is now working systematically to destroy nearly all of those earlier advantages. Immigrants are no longer welcome in the U.S.; visiting scholars have been unreasonably detained at the U.S. border or in some cases even deported from American campuses. A number of foreign governments have issued travel advisories warning about possible dangers of travel to the U.S. under this administration. The pernicious partisan polarization in the U.S., coupled with Trump’s rather arbitrary tariffs imposed on all the world’s countries, have raised legitimate questions about the continued governmental and economic stability of the U.S.

Trump’s vicious attacks on America’s finest universities, including Harvard and Columbia – made under the not credible pretext of protecting against antisemitism on campus — threaten the very policies that have made U.S. universities so attractive: faculty governance and academic freedom. He has withheld all federal funds for research at Harvard and threatens to do so to other universities that don’t cede control to him. Republican-led states are following Trump’s lead. For example, Texas state Senate Bill 37, recently signed into law by the Governor, will transfer power over faculty governance, faculty hiring, and even curriculum development, at state universities from faculty to Governor-appointed governing boards and the university Presidents. This will start a trend toward government control over what is taught and what research is funded, in order to support only the government’s viewpoints. The Indiana state legislature has already instituted policies that can deny or revoke tenure from faculty members at state universities who do not teach with “intellectual diversity” as defined by individual students and Governor-appointed trustees.

Needless to say, these attacks on research universities, combined with Trump’s proposed draconian cuts to research funding, especially on topics he doesn’t like – prominently, climate change, sex and gender, vaccine development – have dampened the optimism of American scientists. The attacks violate current U.S. law as interpreted in Sweezy v. New Hampshire, where Chief Justice Earl Warren laid out “four essential freedoms” of a university: “to determine for itself on academic grounds who may teach, what may be taught, how it shall be taught, and who may be admitted to study.”

Trump’s policies are thus very likely to reverse the trend of the past three-quarters of a century, in which American science and technology benefited enormously from a “brain gain” from other countries. These policies will almost certainly lead to a brain drain of scientists from the U.S. and to a stalled flow of foreign scientists and students into American institutions. Not to worry, says Vice President JD Vance (see Fig. I.2). In an interview on the Trump-friendly cable news channel Newsmax, Vance displayed his limited understanding of both the concept of a brain drain and the history of American science:

“I’ve heard a lot of the criticisms, the fear, that we’re going to have a brain drain. If you go back to the ’50s and ’60s, the American space program, the program that was the first to put a human being on the surface of the moon, was built by American citizens, some German and Jewish scientists who had come over during World War II, but mostly by American citizens who had built an incredible space program with American talent. This idea that American citizens don’t have the talent to do great things, that you have to import a foreign class of servants and professors to do these things, I just reject that.”

There are many problems with Vance’s statement. First of all, a brain drain implies not only that foreign scientists (not “servants”!) will stop emigrating to the U.S. but also that American scientists will leave for other countries. It is already starting with young American scientists and a dozen other countries, including much of western Europe, Canada, Australia, and even China, have launched serious recruitment efforts to attract the best U.S. scientists who are dismayed or dismissed by Trump’s anti-science policies. Second, a brain drain in no way implies, as Vance suggests, that American citizens lack talent; rather it implies that the most talented citizen scientists are going to be highly recruited by other countries and many will be tempted to leave for countries where research funding is not contingent on support for the government’s ideological prejudices.

Third, the lone example Vance chooses to show that American scientists don’t need foreign immigrants is laughable. In lauding the U.S. space program as American-built, he ignores the critical contributions made by Wernher Von Braun and his large German rocket team, brought to the U.S. after World War II in a military operation specifically to transfer the techniques and details of rocket design they had mastered during the war in Germany. Von Braun and his team designed and built the Saturn V launch vehicle that served as the rocket booster for the first voyage to the Moon that Vance chooses to highlight. This was hardly an incidental contribution.

More generally, American science across many fields has been manifestly enhanced by the attractiveness of U.S. research institutions to immigrants, and Donald Trump is making that attractiveness a thing of the past. In the rest of this post, we will explore in more detail: the exodus of scientists from Nazi-occupied Europe (Section II); U.S. post-war policies that attracted great scientists (Section III); Trump policies undoing previous U.S. advantages (Section IV); and ongoing recruitment efforts to attract U.S. scientists to other countries (Section V). We will summarize in Section VI.

II. exodus of scientists from nazi-occupied europe

The exodus of scholars from Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe during the buildup to World War II represents the classic example of a brain drain. Adolf Hitler wasted no time in imposing his own obsessions on German government policy. Two months after he was appointed Chancellor in 1933 his government issued the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Service. According to this law and its subsequent updates, anyone who had at least one Jewish grandparent and anyone judged to be an opponent of the Nazi Party was to be immediately dismissed from any government-funded position. This included academics at Germany’s best universities, as well as teachers, judges, and police officers. A second law called for the disbarment of any non-Aryan lawyer. Even those not directly affected could read the writing on the wall.

An Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced German Scholars was established in the U.S. in 1933 by Professor Philip Schwarz to help the persecuted find positions in other countries. Famed American newsman Edward R. Murrow became the unpaid Assistant Secretary of the Committee. An analogous effort was launched in the U.K. by British economist William Beveridge. Nobel Prize-winning physicist Ernest Rutherford – the discoverer of the atomic nucleus – was the first President of the British committee, initially named the Academic Assistance Council and later renamed as the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning (SPSL).

The List of Displaced German Scholars the American Committee put out in 1936 included nearly 1800 names covering a variety of disciplines. As Nazi occupation spread throughout Europe and Italy was under the collaborating Fascist government of Mussolini, the Committee changed its focus from only Displaced German Scholars to Displaced Foreign Scholars, including scholars forced out of Austria, Czechoslovakia, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Italy. The U.S. and U.K. were main beneficiaries of the Nazi brain drain. By the end of World War II, the British SPSL had helped more than 2500 scholars displaced from Germany and Nazi-occupied countries escape. The American Committee rescued more than 300 scholars, aided during the Great Depression by funding provided by the Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Foundation.

The brain drain included many of the most prominent European scientists, composers, artists, writers, and other cultural leaders. Sigmund Freud spent his later years in the U.K. Among the many illustrious refugees to America were psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, composers Béla Bartók, Igor Stravinsky, Paul Hindemith, and Arnold Schoenberg, conductors Arturo Toscanini and Bruno Walter, pianists Vladimir Horowitz and Artur Rubinstein, artists Marc Chagall, Marcel Duchamp, Piet Mondrian, and Ferdinand Léger, novelists Vladimir Nabokov, Thomas Mann, Erich Maria Remarque, and André Maurois, architects Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, and mathematician John Von Neumann.

Among the scientists, the physicists were particularly impactful. 15% of German physicists were displaced and these accounted for 64% of all German physics citations before Hitler’s purge. The names of physicists who emigrated from their European home countries during the pre-war years reads like a Who’s Who of 20th century physics. Emigrés who landed in the U.S. included:

- Albert Einstein, who won the Nobel Prize in 1921;

- James Franck, who shared the Nobel Prize in 1925;

- Enrico Fermi, who won the Nobel Prize in 1938;

- Otto Stern, who was to win the Nobel Prize in 1943;

- Felix Bloch, who was to win the Nobel Prize in 1952;

- Emilio Segré, who was to share the Nobel Prize in 1959;

- Eugene Wigner, who was to share the Nobel Prize in 1963;

- Maria Goeppert-Mayer, who shared the 1963 Prize with Wigner;

- Hans Bethe, who was to win the Nobel Prize in 1967;

- George Gamow, whose later work on the formation of light nuclei in the early universe helped to establish the Big Bang model of the universe’s birth;

- Leo Szilard, whose appreciation of the possibility of an atomic bomb after the discovery of nuclear fission was critical in launching the Manhattan Project;

- Edward Teller, who was to become the “father” of the hydrogen bomb;

- Victor Weisskopf, who became a major figure in the development of nuclear theory;

- Fritz London, who made fundamental contributions to theories of chemical bonding, intermolecular forces, and properties of superconductors.

Many of these pre-war immigrant physicists arrived in the U.S. when they were still in their 20s or early 30s and their best work was still ahead. And of the children who arrived in the U.S. with their migrating German families, three have gone on subsequently to win Nobel Prizes in Physics: Arno Penzias (1978) for the discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation whose study is central to our understanding of the evolution of the universe; Jack Steinberger (1988) shared the prize for the experimental discovery of a second type of neutrino, crucial for our understanding of the fundamental particles of nature; and Rainer Weiss (2017) for the experimental discovery of gravitational waves, confirming a central prediction of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, made a century earlier.

Other world-leading emigré physicists ended up in countries outside the U.S. Erwin Schrödinger, who shared the 1933 Nobel Prize in Physics for his development of quantum mechanics, ended up in Ireland after a disastrous stay in Austria, where he tried briefly to ingratiate himself with Hitler after the 1938 Nazi annexation of Austria. Max Born, who was to share the 1954 Nobel Prize in Physics for his fundamental contributions to the birth of quantum mechanics, migrated to the U.K., where he spent time at the University of Cambridge and 16 years as the Tait Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. Lise Meitner and her nephew Otto Frisch, who together provided the theoretical understanding of nuclear fission after it had been discovered experimentally in December, 1938 in the laboratory of Otto Hahn, both left Germany. Frisch went to work with Niels Bohr (1922 Nobel Prize) in Copenhagen. Meitner, who was denied a well-deserved share of Otto Hahn’s 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the fission discovery, ended up in Sweden. Bohr, who had personally intervened to help many of the emigrés to find positions, had to relocate himself in 1943 after he learned that the Nazis who then occupied Denmark considered his family to be Jewish, since his mother was Jewish. From 1943 to 1945 Bohr divided time between Sweden and the U.K. and visited the U.S. many times to discuss their progress on the atomic bomb.

The discovery of nuclear fission changed the world almost overnight. The history of the months following the discovery and the central roles of the immigrant physicists has been retold by Fermi’s wife Laura Fermi in her 1968 book Illustrious Immigrants: The Intellectual Migration from Europe 1930-41. Bohr arrived in the U.S. from Denmark on Jan. 16, 1939 and brought to colleagues at Princeton and Columbia Universities the fresh news that the fission of uranium, induced by neutrons, had just been discovered in Nazi Germany. Ten days later at a conference in Washington, D.C. organized (for other reasons) by Gamow and Teller, Bohr and Fermi discussed with colleagues the possibility that neutrons were emitted in uranium fission, raising the possibility of a chain reaction (see Fig. II.1). Leo Szilard was one of the first to grasp the real possibility that such a chain reaction could potentially fuel an extremely powerful bomb, also that Germany probably had a headstart on just such a development.

It was Szilard and Wigner who prepared a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt pointing out the disastrous possibility that Germany was working on a fission bomb and urging U.S. action. On the advice of economist Alexander Sachs, they got Einstein to sign the letter because Sachs believed Einstein was the only scientist with sufficient stature in the U.S. to get the President’s attention. The letter was dated Aug. 2, 1939, but since World War II had by then broken out, it was not until October that Sachs was able to deliver the letter personally to Roosevelt. An Advisory Committee on Uranium was organized at once, including representation from the U.S. Army and Navy, later adding several scientists under the revised title of the National Defense Research Committee.

Teams at Columbia, under the leadership of Fermi and Szilard, and at Princeton, under the leadership of Wigner and the American physicist John Wheeler, began work on understanding the possibility and the conditions under which a chain reaction might be successfully initiated. Fermi and Szilard came to the conclusion that the most promising way to achieve a controlled chain reaction involved constructing a pile of alternating graphite and uranium sheets, and they needed large quantities of both materials to be supplied with unprecedented purity.

Another group at Columbia under the American physical chemist Harold Urey was working on separation of uranium isotopes. The University of California at Berkeley got involved because it had a large cyclotron, a particle accelerator that had been invented by American physicist Ernest Lawrence, for which he won the 1939 Nobel Prize in Physics. Lawrence was working with Segré on the possibility of using the cyclotron to produce plutonium as a possible fission fuel.

In all of this work there was very close collaboration between recent European immigrants and American physicists, even though the Germans and Italians, in particular, were considered enemy aliens and were restricted in their living arrangements and travel. It was the openness of American scientists that welcomed such collaboration with recent arrivals, but it was the Europeans, who had seen Hitler and Mussolini up close, who established the sense of urgency to determine as quickly as possible if a bomb was possible and to beat Germany to the punch.

After Pearl Harbor, many scientists put aside their own work and joined the war effort. The attempt to build a pile and demonstrate a chain reaction was moved to the University of Chicago. The nominal head of the project was American Nobel Prize winner and Chicago faculty member Arthur Compton. But the driving forces behind the work were Fermi, Szilard, and Wigner (see Fig. II.2). In Laura Fermi’s description: “Szilard threw out ideas; with his practical intuition Fermi turned them into rough theories that served immediately to guide experiments; and Wigner, more patient and rigorous, refined them into mathematically cogent theories that would stand the test of time.” Under Fermi’s guidance, the pile built under the stands of a football field at the University of Chicago demonstrated a self-sustained, controlled uranium fission chain reaction on Dec. 2, 1942. It was the world’s first instance of man-made atomic energy production.

Meanwhile, in the summer of 1942 the American (but European-trained) theorist Robert Oppenheimer had gathered a small group in Berkeley, including the prominent recent immigrants Hans Bethe (see Fig. II.3), Edward Teller, and Felix Bloch. Under the optimistic assumption that the Chicago pile would demonstrate a self-sustained chain reaction, they were trying to estimate how much fissionable material it would take to produce the uncontrolled chain reaction needed for an atomic bomb.

Despite the remaining daunting uncertainties about whether it would all work and how sufficient fissionable material – either enriched uranium-235 or plutonium produced by a nuclear reaction induced in uranium-238 — could be assembled on a compressed time scale, the U.S. government launched the Manhattan Project in summer of 1942 with General Leslie Groves in charge. Groves proceeded with a sense of great urgency and deep confidence in the scientists working on the project, including the foreign scientists, even the “enemy aliens.” In 1943 Groves drove the project to “the stage that Europe could not have matched —jumping directly from laboratory experiments to immense industrial plants, even before the small experiments were complete; the decision to try different approaches and costly large-scale processes in order to see which would work best; and the sudden multiplication of scientists, engineers, technicians, and business and military men needed to turn atomic research into a huge crash program. European nations did not have the money, the broad vision, or the faith that were required, nor did they have the concentration of brain power. Its best brains had emigrated.”

Groves divided the main scientific and engineering tasks among three main sites. Large piles were to be constructed at Hanford, Washington; isotope separation of uranium-235 was to be done in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The major responsibility of constructing a working bomb was assigned to Los Alamos, New Mexico under the scientific leadership of Oppenheimer. The major presence of recent European immigrants was at Los Alamos. Bethe, Segré, Teller, and Weiskopf, along with others including Stanislaw Ulam, Bruno Rossi, and Hans Staub, were at Los Alamos for the entire duration of the Manhattan Project. Bethe led the theory group. Fermi came in the summer of 1944 to serve as Associate Director of Research and Division Leader. Neils Bohr and the Hungarian mathematician John Von Neumann paid frequent visits. There were, of course, also many American scientists, including the promising young theorist and future Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman. Groves was bemused by all the scientists interacting strongly on this isolated mesa in New Mexico; he is said to have remarked “At great expense we have collected here the greatest collection of crackpots ever seen.”

The crackpots got the job done. On July 16, 1945 the world’s first atomic bomb was successfully tested at the Trinity desert site in southern New Mexico. The first test was of a plutonium bomb triggered by an implosion mechanism that had been pushed by Von Neumann, Teller, and the Russian-born chemist George Kistiakowsky. Despite the misgivings of many of the scientists involved, new President Harry Truman made the decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima (uranium bomb) and Nagasaki (plutonium implosion bomb) on Aug. 6 and 9, 1945 to give a terrifying, mass-destruction demonstration of the power the U.S. had attained and bring a definitive end to World War II.

Laura Fermi sums up the European immigrants’ role in this enormous undertaking this way: “…they were a most influential minority. It is difficult to conceive of the atomic project without them, without the correlation between theory and experiment that the early comers had promoted, or the stubbornness that Szilard, Wigner, and Fermi displayed in the first few years after the discovery of fission, when they stuck to research that others deemed unpromising, without their dedication and hard work, their intellectual leadership and confidence in the ultimate outcome of the project and its power to end the war. On the other hand, it is even more difficult to imagine a group of foreign-born scientists attaining the same degree of success in isolation, outside the great compound of American industry, without the leadership of men like Compton and Oppenheimer and without the collaboration of hundreds of American scientists, the young as well as the mature, the obscure as well as the prominent.” One of the German scientists captured after the war and surveilled at Farm Hall in England said in private that such “cooperation on a tremendous scale…would have been impossible in Germany.”

The wave of pre-war scientists emigrating from fascist Europe had rapidly assimilated in American life, had provided an extraordinary wartime defense of the United States, and had begun to transform American science. They represented the first wave of a remarkable scientific brain gain the U.S. has benefited from for the better part of a century, right up until the beginning of 2025.

III. U.S. post-war policies that attracted great scientists

The U.S. government understood how critical scientists were to the country’s defense during World War II and the essential role that had been played by immigrant scientists. It had the vision to foresee that healthy support for scientific research and a welcoming attitude toward immigrant scientists and students would help to fuel a rapid post-war expansion of the American economy. The architect of this visionary post-war science policy was Vannevar Bush.

A. Vannevar Bush and The Endless Frontier

VannevarBush was a skilled engineerand a pioneer in digital circuit theory. But it was his work as a scientific policymaker and administrator that led to his most lasting contributions to American science. During World War II, Bush became chair of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD). In that role he coordinated the efforts of six thousand top American and world scientists, in contributing their scientific talents to efforts to win the war. One of his signal achievements during World War II was his initiation of the Manhattan Project that led to the construction of the atomic bomb. Bush was also the de facto scientific advisor to President Roosevelt and later Truman.

At the end of World War II, Bush wrote a 1945 report to President Truman called Science, the Endless Frontier (Fig. III.1). In that report Bush outlined his vision for federal funding of pure and applied research in the physical and medical sciences. This was a radically new concept, where a fairly autonomous federal agency would oversee the funding of scientific research. It took until 1950 when the National Science Foundation (NSF) was created. But Bush was clearly the originator of this idea, as he pushed the notion that “Basic research is the pacemaker of technological progress.”

Bush stressed “The Five Fundamentals,” underlying principles for this new national science agency:

- Stability and continuity of funding;

- Administration of grants by citizens with deep understanding of scientific research and education;

- The agency should not operate laboratories of its own;

- The grant environment should be controlled by universities and research institutes;

- Accountability to Congress and the President.

Even today Bush’s report Science, The Endless Frontier is relevant and far-sighted. Bush stated that “Science has been in the wings. It should be brought to the center of the stage – for in it lies much of our hope for the future.” He furthermore was clear about the importance of supporting science education and free inquiry:

“To encourage and enable a larger number of young men and women of ability to take up science as a career, and in order gradually to reduce the deficit of trained scientific personnel, it is recommended that provision be made for a reasonable number of (a) undergraduate scholarships and graduate fellowships and (b) fellowships for advanced training and fundamental research… and care should be taken not to impair the freedom of the institutions and individuals concerned.”

Bush also strongly advocated for “supporting international cooperation in science” and the international exchange of scientific findings. When he wrote the report, the influx of foreign scientists was still somewhat limited by U.S. immigration laws, as we’ll see below. But the attitudes promoted in the report led later to strong efforts to attract the best foreign scientists and students to the U.S. In the current climate, where expertise has been discarded in favor of loyalty and immigration has been militantly discouraged, we may well learn a painful lesson that investments in basic research, the nurturing of young scientists, and attracting the best foreign scientists represent essential elements in keeping our country strong, competitive and prosperous.

The creation of the NSF could not have come at a more propitious time. In World War II the federal government had funded and directed a coalition of scientists, corporations and the Defense Department to spur developments such as advanced radar, aviation technology, and the Manhattan Project. The many immigrants who had fled repressive regimes for the United States were working at universities, national laboratories and private corporations. As we will show in the next section, revised immigration policies made it attractive for talented students to attend elite American universities. The result was a veritable explosion of scientific discoveries, many of which had profound applications to science, medicine, computing, and other fields.

Until the recent chaotic cuts in federal funding to science under Trump 2.0, agencies such as the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Department of Energy have spent billions of dollars supporting basic and applied research. Advances in areas such as laser technology, nanotechnology, genetics, public health, supercomputers, the Internet, artificial intelligence, and nuclear and renewable power have all benefited from seminal advances made by federally-supported research groups and then carried on by private corporations. A significant fraction of our nation’s Gross Domestic Product results from the applications of breakthroughs made with federal funding. And Vannevar Bush’s vision, as well as his outstanding leadership qualities, allowed the U.S. to achieve world leadership in basic research, medical science, and applications of technology.

B. Changes to Immigration Policies:

Prior to 1965, the U.S. policy on immigration was based on the 1924 Immigration Act, which was passed during the Eugenics era. That act prohibited immigration from Asian countries and imposed strict limits on immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe. The 1924 immigration law established a “National Origins Formula,” which was based on infamous arguments by Eugenics advocates that Southern and Eastern European citizens, as well as Asians and Africans, were inferior in intelligence to Western and Northern Europeans. In his autobiography Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler wrote of his admiration for American immigration policy, “The American Union categorically refuses the immigration of physically unhealthy elements, and simply excludes the immigration of certain races.”

However, in the period just before the start of World War II, and continuing through the early years of that war, the U.S. welcomed many immigrants from European countries. This was described in Section II of this post. In the field of science, the U.S. gained a tremendous amount of European brainpower that made extraordinary contributions to American science. As outlined in Section II, European scientists played a leading role in the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb. Figure III.2 shows the group that created the first controlled nuclear chain reaction, the “atomic pile,” at the University of Chicago. Italian immigrant and Nobel laureate Enrico Fermi is far left in the front row. Prior to World War II, the center of world science was largely in Europe. In particular, Germany was the leader in the new field of quantum physics.

But American physicists such as Robert Oppenheimer and Ernest Lawrence were introduced to this new field by contacts with European scientists, and when they returned to the U.S. they established promising research groups in this country. Also, the brain drain from Germany and other European countries provided a stream of great scientists who made extraordinary contributions to American science and technology. After World War II, most countries in Europe and Asia were rebuilding from the ravages of war. However, the U.S. was building up enormous talent, both foreign and domestic, in its universities, national laboratories and corporate research labs. Scientists from all over the world were attracted to these American institutions, which offered a great deal of freedom to follow new scientific directions. These American scientific centers also attracted many of the world’s best young students and junior researchers.

Immigration to the U.S. was enhanced by the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. This Act was signed by Lyndon Johnson and marked the culmination of a long and difficult campaign to repeal the National Origins Formula. In his inaugural address in January 1965, President Johnson made immigration reform the top priority of his administration. This law repealed the strict quotas enforced on immigration from Southern and Eastern European countries, and it also liberalized immigration policy for Asians. A result of this Act was a significant increase in immigration from Latin countries and from Asia. American science was greatly enhanced by contributions from immigrants. Later in this section we give three examples of first-generation immigrants who won Nobel Prizes for their outstanding research.

C. Solidification of Academic Freedom

Along with liberalized immigration policies, the U.S. became the leading country in science and technology because of the excellence of its universities. These centers of learning became the greatest in the world, and the academic freedom provided to American colleges played a major role in attracting scientific talent from around the world. A major step forward occurred in 1957 when the U.S. Supreme Court recognized a First Amendment right of institutional academic freedom: “It is the business of a university to provide that atmosphere which is most conducive to speculation, experiment, and creation. It is an atmosphere in which there prevail the ‘four essential freedoms’ of a university – to determine for itself on academic grounds who may teach, what may be taught, how it shall be taught, and who may be admitted to study.”

The autonomy of universities allowed them to build up areas of science where they could excel. Academic freedom also extended to the freedom of faculty to do research in areas of interest to them. The relative freedom of American universities attracted both scientists and students from all over the world. These international scientists contributed their talents to produce worldwide centers of excellence. American universities included Ivy League institutions that were some of the oldest colleges in the country. Regional centers such as the Midwest, the South and the West Coast developed public universities that rapidly developed into world-class research centers.

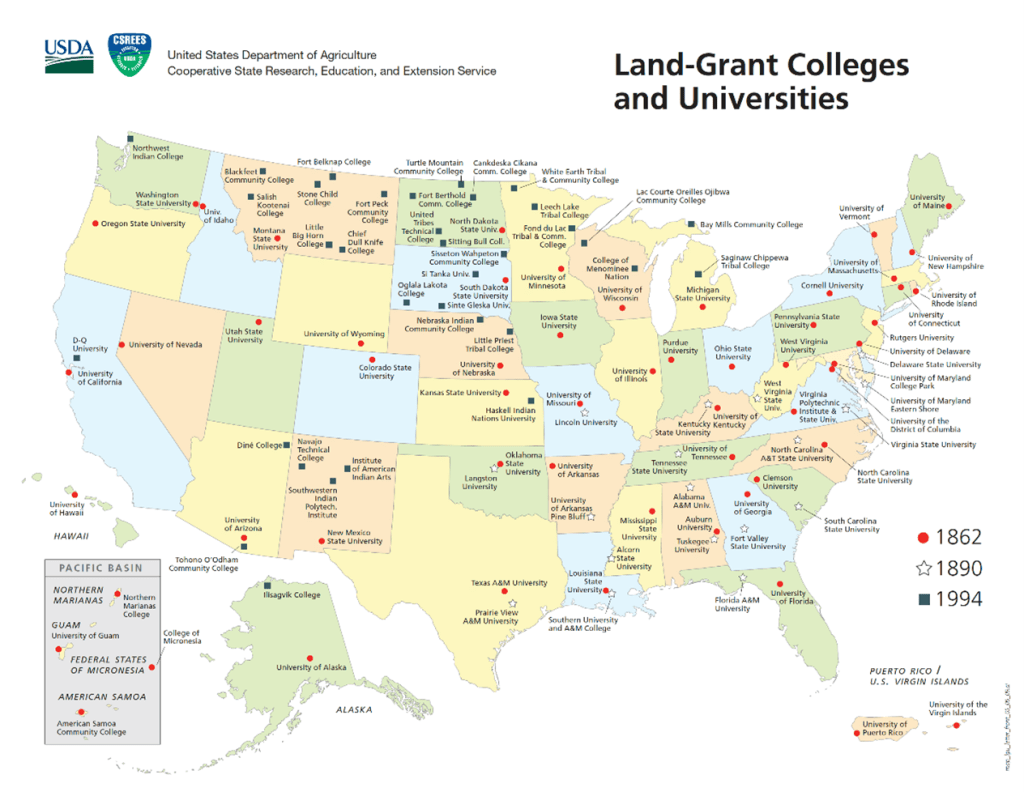

In 1862 Congress passed the Morrill Act that established land-grant colleges in each Northern state. Initially, those colleges focused explicitly on topics such as agriculture, engineering, science and military science. In 1890 a second Morrill Act expanded land-grant schools to additional states and also created land-grant colleges for African-Americans. Finally, in 1994 land-grant status was extended to schools for Native Americans. Figure III.4 shows the land-grant colleges and universities in the U.S. Solid red circles denote land-grant schools created by the 1862 Morrill Act; open stars denote schools created by the 1890 Morrill Act, and solid blue squares denote schools created by the 1994 act. Every state in the U.S. has at least one land-grant school.

The postwar period in the U.S. saw the growth of science in American universities, national laboratories, and also some prestigious industrial labs such as Bell Labs and the IBM laboratories. The industrial laboratories were responsible for a number of breakthroughs in basic research. One reason for their success is that their corporate research groups were modeled after basic research carried out at universities. The transistor and the laser were developed at Bell Labs, as was the field of information theory. IBM labs pioneered research in computing and more recently quantum computing, high-temperature superconductivity and the technology used in LASIK eye surgery. Both American universities and some corporate laboratories carried out fundamental research that led to enormously successful applied technology.

D: Growth in Federal Research Funding

Starting in the 1950s, the elements needed to produce the American dominance in research in science and medicine were in place. Liberalized immigration policies before and during World War II had allowed the U.S. to admit world-class scientists who faced harassment or death to leave Europe and head to the United States. After World War II, new immigration policies had allowed scientists from Asia, Southern and Eastern Europe to bring their talents to America. Over time, bright international students were attracted to the U.S. from many other countries. Not only did they inspire American students with their intelligence and drive, but many international students remained in this country after they finished their degrees. In Section I, we documented the numbers of first-generation immigrant Americans who have won Nobel prizes. Such immigrants have made enormous contributions to American science and technology.

A second major contribution to American science dominance was the quality and openness of American universities. The guarantees of autonomy and academic freedom that emerged from the Earl Warren Supreme Court helped make American universities the envy of the world. Scientists who experienced restrictions and stifling bureaucracies in their home countries found freedom in the U.S. These scientific leaders also inspired many young scientists to immigrate to the U.S.

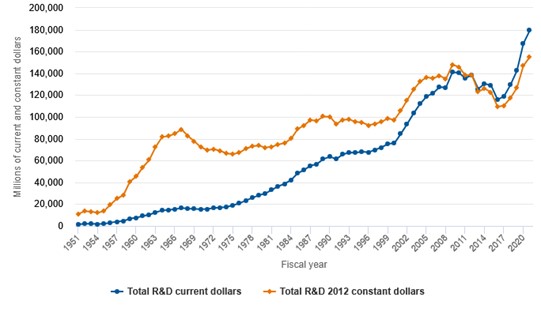

The final element that fueled the American resurgence in science and technology was the existence of federal funding. This was inspired by Vannevar Bush’s 1945 report Science: the Endless Frontier, which we reviewed in an earlier section. This called for substantial, sustained and reliable federal funding of research and technology. The non-defense federal funding for research and development is mainly distributed through a number of federal agencies. Figure III.5 shows the total federal R&D spending from 1951 to 2020. The blue dots are in at-year dollars, while the red dots represent the total R&D funding in constant 2012 dollars. Note that in 2020 the total federal R&D funding was $180 billion. The results of this federal support have made the U.S. medical research the top in the world. American research and technology have produced pharmaceutical and medical-products industries that are the best in their fields.

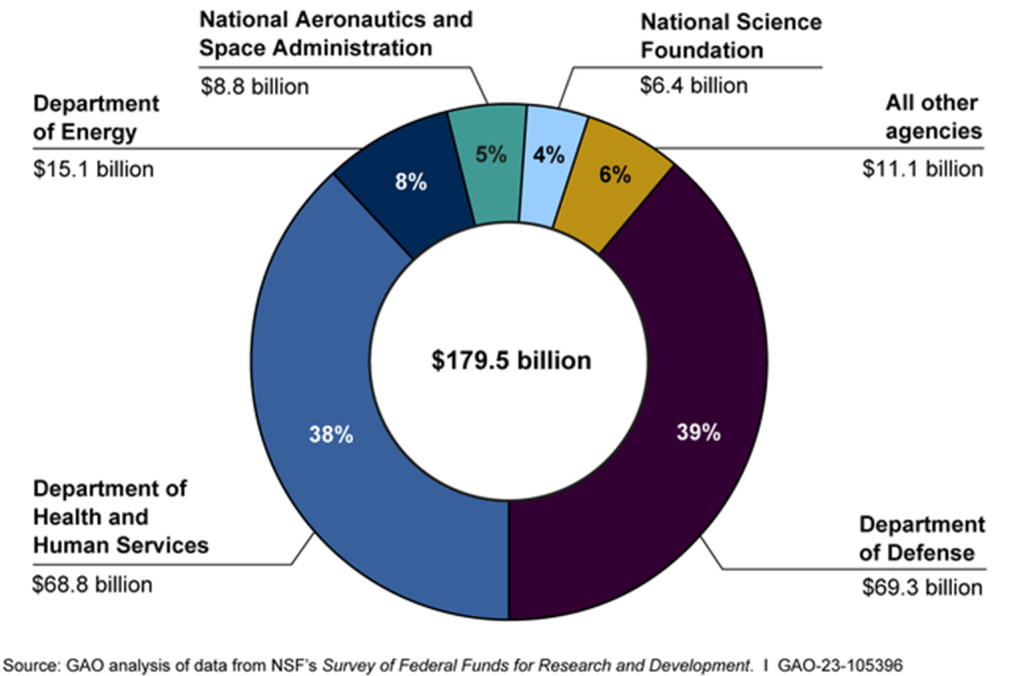

Figure III.6 shows the breakdown of federal R&D spending over various agencies. The total amount for fiscal 2021 was $179.5 billion. Of this amount, about 38% each was allotted to the Department of Health and Human Services and the Defense Department; the Department of Energy received $15.1 billion; NASA $8.8 billion, the NSF $6.4 billion; and all other agencies received $11.1 billion. This results in enormous returns for our economy. A 2023 study of the National Institutes of Health estimated that every dollar invested in NIH produces $2.56 in new economic activity. For example, NIH-sponsored research led to the discovery of the connection between cholesterol and heart disease. Subsequent studies have produced cholesterol-lowering medications that have produced a 67.6% decrease in heart disease deaths from 1969 to 2015. Clearly, investments in research and development create jobs and fuel the U.S. economy.

E: Examples of Nobel Prize-Winning Immigrants to the U.S.

The foreign scientists attracted to the U.S. by the combination of outstanding institutions, academic freedom, healthy and consistent research funding, and welcoming immigration policies have been of outstanding quality. As we have mentioned, 40% of Nobel Prizes awarded to American scientists in the 21st century have been won by first-generation immigrants to this country. In fact, there have been only four years between 2000 and 2023 when there was not at least one immigrant American scientist awarded a Nobel Prize in physics, chemistry, or medicine. American science has been enriched incredibly by these immigrants. In particular, American research and development has been the driving force behind the prosperity of the U.S. since World War II. Here, we will provide representative capsule biographies of three of the immigrants who have won a science Nobel Prize in the past 30 years.

Mario Molina: Mario Molina, whose photo is shown in Fig. III.7, was born in Mexico in 1943. He had a burning interest in chemistry and obtained his Ph.D. in physical chemistry at the University of California at Berkeley in 1968. He then obtained a position at the University of California, Davis. There he joined with his chemistry colleague Sherrill Rowland to embark on a study of the behavior of chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) molecules in the atmosphere.

Rowland and Molina discovered that when CFCs were released into the atmosphere, they would remain inert until they reached the ozone layer in the upper stratosphere. Above the ozone layer, there are abundant levels of UV-B radiation from the Sun. However, the ozone layer filters out UV-B rays so below that level there is almost no UV-B radiation. Rowland and Molina showed that UV-B rays could decompose CFC molecules, releasing an atom of chlorine (Cl). The Cl atom would then initiate a catalytic reaction where it would destroy an ozone molecule. Rowland and Molina found that a single Cl atom could destroy 100,000 molecules of ozone. They realized that Cl had the potential to destroy the ozone layer; this would be catastrophic for our society, as the larger amount of UV-B radiation reaching the Earth’s surface would cause disastrously large numbers of skin cancer and melanoma in humans, as well as similar deleterious effects in plants and animals.

The potential danger from CFCs caused Rowland and Molina to call for a ban on these products. For about a decade, scientists sparred with chemical companies who disputed their findings. However, in 1985 a large “hole” was discovered in the ozone layer above Antarctica. The “hole” appeared in the Antarctic spring, and it is shown for six consecutive years beginning in 1979 in Fig. III.8. This finding, which showed a much more serious ozone depletion than had been discovered at mid-latitudes, increased calls for a CFC ban. In 1987 an international agreement, the Montreal Protocol which called for a ban on the use of CFCs, was signed by 56 countries. Today, the Montreal Protocol has been signed by every nation. Today, the damage to the ozone layer is slowly decreasing; the process is slow because CFCs remain in the atmosphere for a century after they are released. The Montreal Protocol also contained both monetary and technical support to Third World countries to replace their CFCs with other chemicals.

For his research, Mario Molina was awarded more than thirty honorary degrees. He was elected to the U.S. National Academy of Sciences in 1993 and the U.S. Institute of Medicine in 1996. He shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Rowland in 1995. He won an impressive array of awards for his outstanding scientific accomplishments; in 1990, the Pew Charitable Trusts Scholars Program in Conservation and the Environment awarded him a grant of $150,000 as part of his being named as one of the ten most prominent environmental scientists. In 2013, President Barack Obama awarded Molina the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his contributions to environmental science. Dr. Molina became the Director of the Mario Molina Center for Energy and Environment in Mexico City. He passed away in October, 2020.

Katalin Karikó: Dr. Katalin Karikó, shown in Fig. III.9, was born in Hungary in 1955. Her father was a butcher, who was punished for participating in the Hungarian uprising for democracy in 1956. She obtained a Ph.D. degree in biochemistry in 1982 from the University of Szeged. She worked at a Hungarian research institute until 1985 when her group lost its funding. Karikó then obtained a postdoctoral fellowship at Temple University, where she participated in clinical trials that used double-sided RNA (dsRNA) to treat various diseases. In 1988, she accepted a research position at Johns Hopkins University; however, she did not inform her research advisor at Temple before accepting this new job. When he discovered that she was leaving, he reported to U.S. immigration officials that she was illegally in the U.S., in an attempt to have her deported. She eventually was successful in challenging an extradition order, but by that time Johns Hopkins had retracted its offer.

In 1989 Dr. Karikó obtained an adjunct faculty position at the University of Pennsylvania, where she continued her research on the use of messenger RNA (mRNA) for gene therapy. However, by the mid-1990s researchers became disenchanted with the prospects of mRNA gene therapy because these RNA products produced inflammatory reactions in vivo. After several of Karikó’s grant applications were rejected, Penn demoted her from her tenure-track faculty position. But in 1997 Karikó began collaborating with Penn immunologist Drew Weissman. The two researchers reached a breakthrough while studying why transfer RNA (tRNA) did not show the same toxicity as mRNA. They showed that by replacing the nucleotide uridine with pseudouridine, the resulting molecules no longer produced toxic reactions. Karikó and Weissman’s paper on this topic was rejected by both Nature and Science but was eventually published in the journal Immunity.

Karikó and Weissman then packaged their mRNA molecules in lipid nanoparticles. Figure III.10 shows a strand of mRNA encased in a lipid nanoparticle. Those nanoparticles protected the mRNA when it was injected, until it reached the desired area of the body. Her work was then utilized by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna in creating an mRNA vaccine to treat COVID-19. The resulting vaccines were developed in record time and proved highly effective against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In addition, mRNA techniques have the potential to treat a number of other diseases, including cancers such as melanoma and pancreatic cancer, cardiovascular disease, and perhaps even a vaccine for HIV.

Karikó and Weissman shared the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their breakthrough contributions to mRNA technology. She has also received more than 130 awards for her research in biochemistry. Her achievements are even more impressive given the unusual number of hurdles she had to overcome before her eventual success. She and Dr. Weissman managed to triumph in an area that had been forsaken by most other researchers but which has enormous potential for improving Americans’ health. If Donald Trump had been President back in 1988, when her Temple advisor reported her as an illegal alien, Karikó would have been deported long before her breakthrough research.

Ardem Patapoutian: Ardem Patapoutian is a molecular biologist who was born in Lebanon to a family that had emigrated from Armenia. His parents survived the Armenian genocide when they fled to Lebanon. Dr. Patapoutian, shown in Fig. III.11, emigrated to the U.S. in 1986 and obtained his Ph.D. degree in biology from Caltech in 1996.

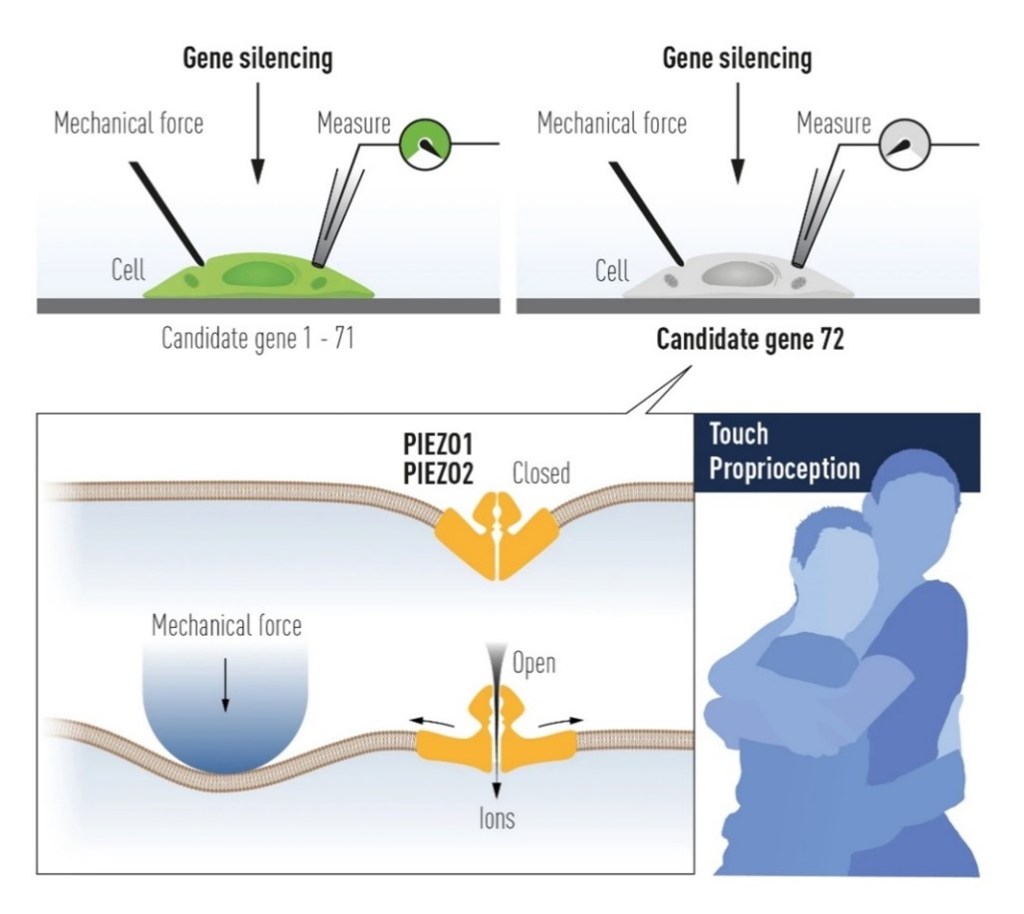

In Dr. Patapoutian’s laboratory, his research team searched for cellular receptors that were activated by mechanical stimuli. They performed experiments that are shown schematically in Fig. III.12. Eventually the group found a cell line that produced an electrical signal when poked by a micropipette. They then inactivated a number of genes to isolate the one responsible for this microsensitivity. Eventually his group isolated the first “mechanosensitive ion channels” which he called PIEZO1 and PIEZO2. Patapoutian’s group showed that these never-before-seen ion channels opened up when pressure was applied to the cell membranes. They demonstrated that the PIEZO2 ion channel was essential for the sense of touch. In addition, PIEZO2 played an important role in sensing body position and motion (known as proprioception). Finally, it has been shown that these two new ion channels regulated physiological processes that include blood pressure, respiration and urinary bladder control.

Dr. Patapoutian is the first Armenian to be awarded a Nobel Prize. He arrived in the U.S. as an immigrant from Lebanon. He showed enormous resourcefulness in obtaining his Ph.D. degree from Caltech and went from there to Scripps Research in La Jolla. His example demonstrates how much the U.S. superiority in science and technology has relied on the exceptional talent brought to this country by immigrants. However, all of our success in this area is imperiled by the procedures set into motion by the current Trump administration.

— Continued in Part II —